Above: Jack Teagarden, Dixie Bailey, Mary Lou Williams, Tadd Dameron, Hank Jones, Dizzy Gillespie and Milt Orent around the piano at Mary Lou Williams’ apartment / Below: the same group in a different order around the phonograph (i.e. turntable)

Above: Jack Teagarden, Dixie Bailey, Mary Lou Williams, Tadd Dameron, Hank Jones, Dizzy Gillespie and Milt Orent around the piano at Mary Lou Williams’ apartment / Below: the same group in a different order around the phonograph (i.e. turntable)

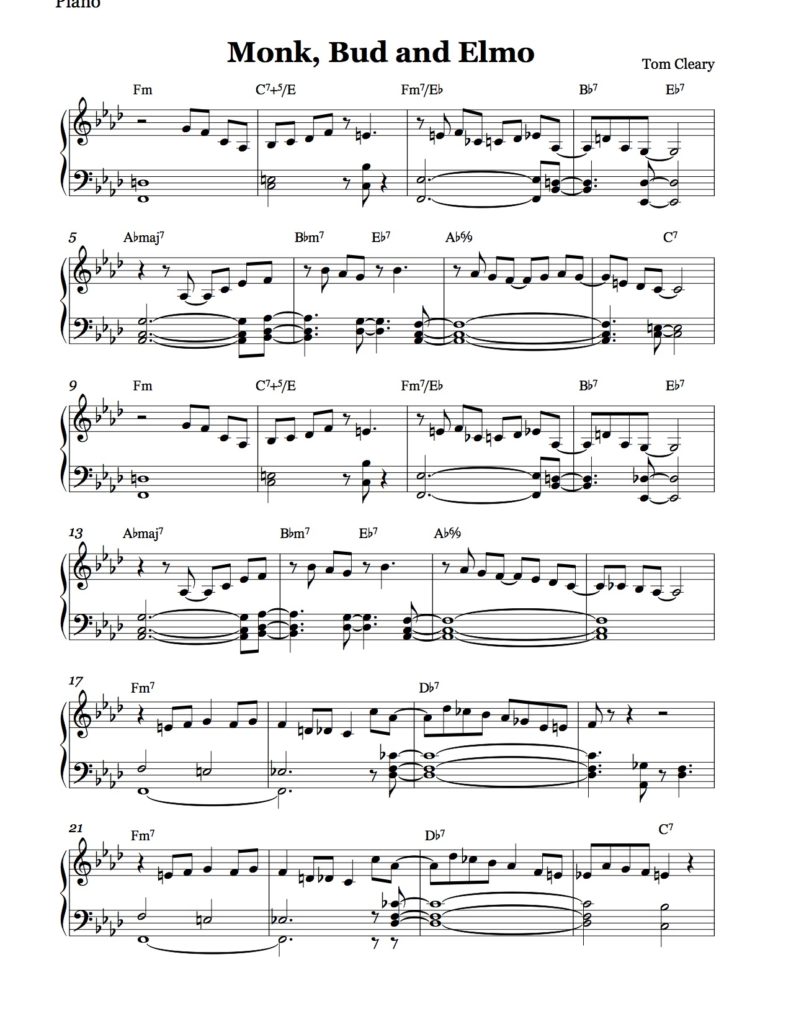

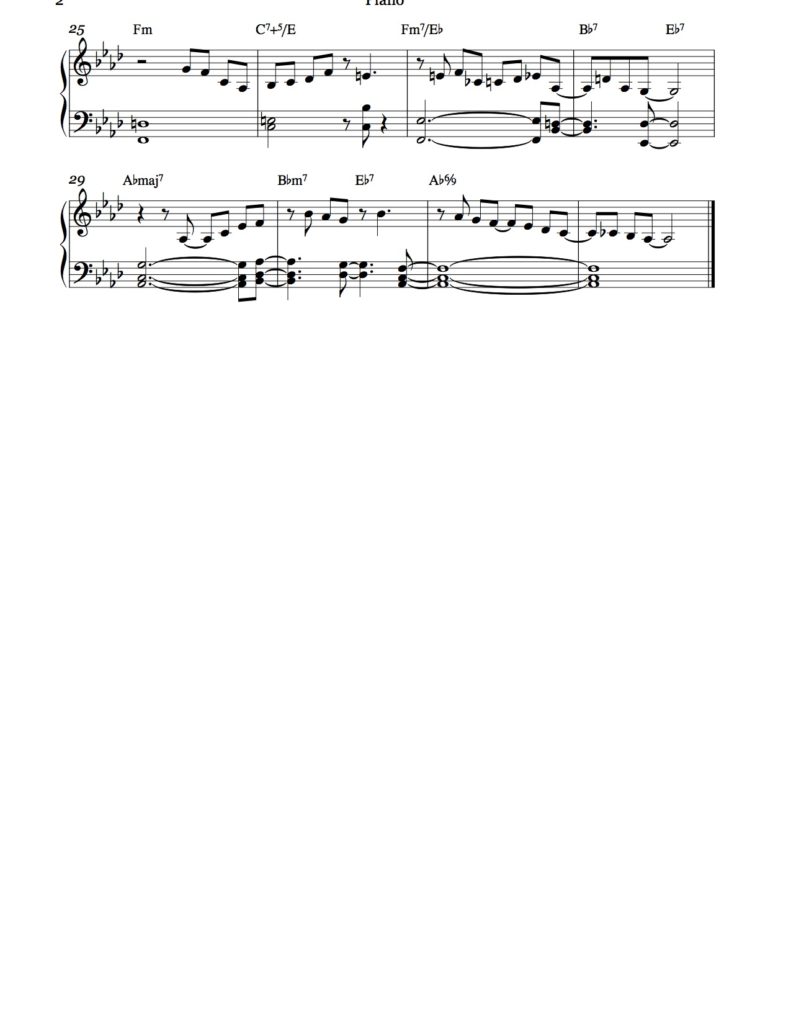

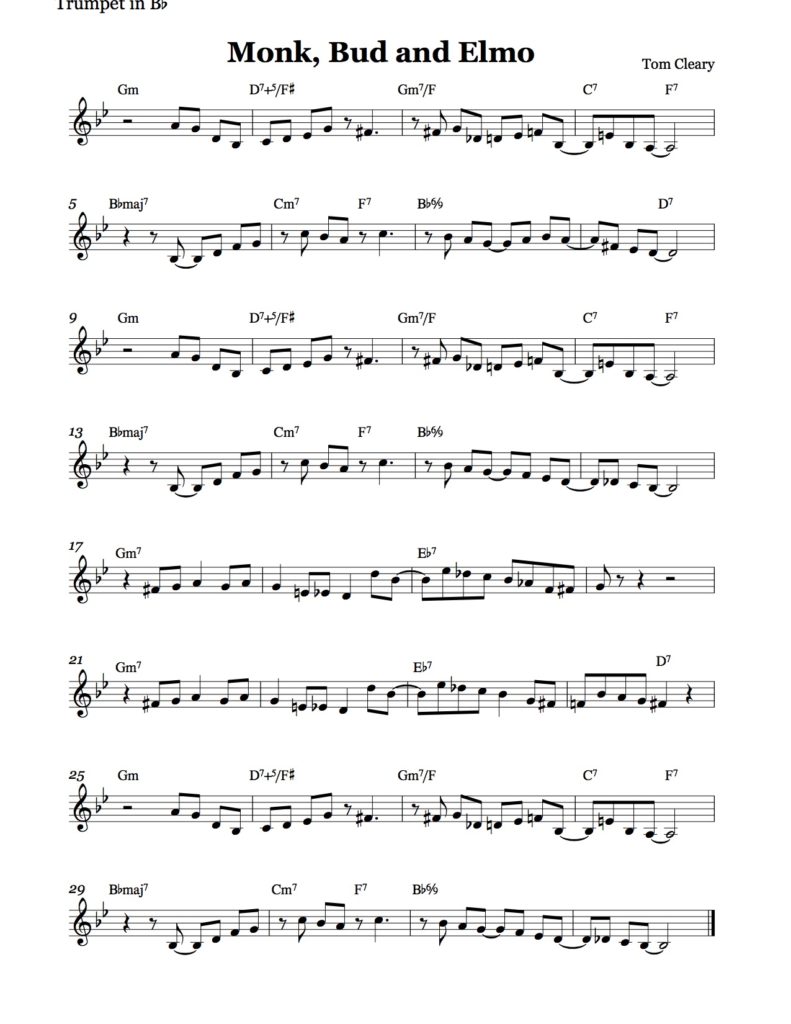

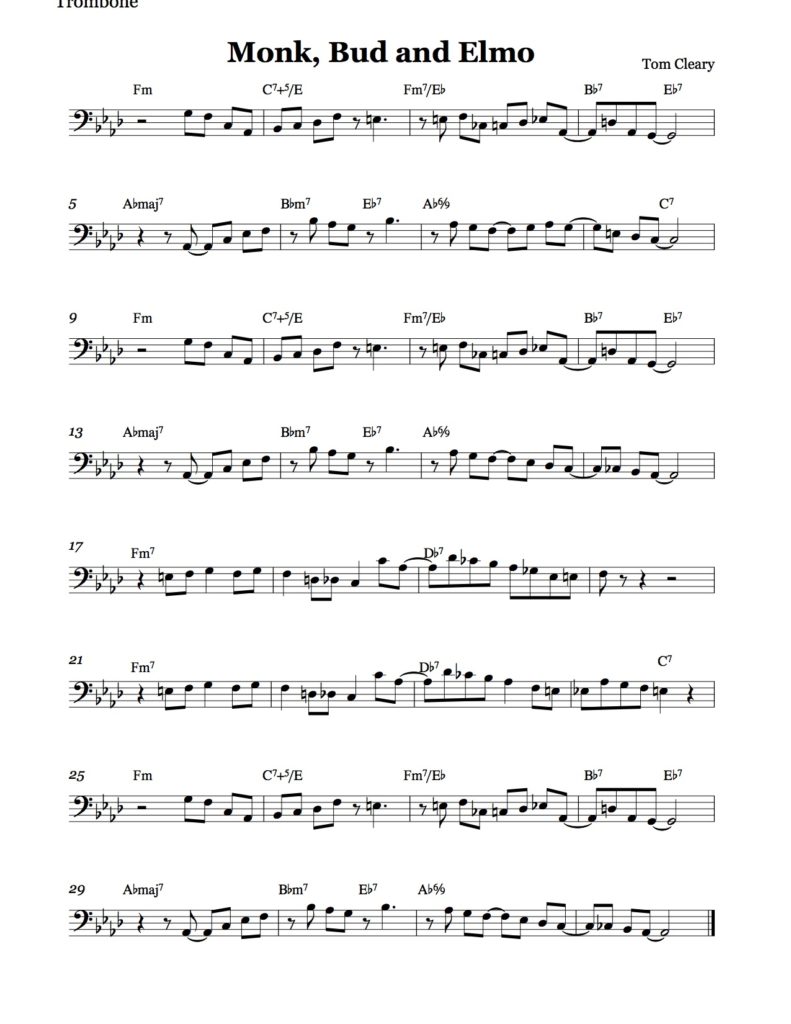

The title of my tune ‘Monk, Bud and Elmo’ refers to a group of now-legendary jazz pianists, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell and Elmo Hope, who hung out together in the early 1940s, before any of them had reached their greatest prominence. Much like an earlier generation of New York pianists (including James P. Johnson, Fats Waller and Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith), the interests that Monk, Powell and Hope shared led them to become a kind of informal club. In his biography of Monk, Robin D.G. Kelley quotes Monk’s sister Marion as saying that once the three musicians “started hanging out together, they were at Monk’s mother’s house ‘all the time’ ”. In his biography of Powell, Peter Pullman quotes saxophonist Johnny Griffin, who recalls “nights when the three pianists, ‘like brothers’, roamed the streets, going from house to house in search of pianos that they could play.” Griffin also comments on how the relationship of the three, who sometimes played four and even six hands at one piano, was competitive in a musical sense, but not a personal one.

The recorded output of all three musicians makes it clear how much they influenced each other. Comparing the versions that Monk, Powell, and Hope recorded of the standard ‘Sweet and Lovely’ reveals how Monk, as the eldest of the group, generated many foundational ideas (such his trademark chromatically descending reharmonization of the tune’s first four measures and his Art Tatum-style right hand runs) which were then adapted by his younger proteges Powell (who uses the runs but stays closer to the tune’s original progression) and Hope (who works his own variation on Monk’s reharmonization.) A comparison of these three players soloing on the blues progression in B flat – Monk’s solo on Straight No Chaser, Bud Powell’s solo on Bud’s Blues (or ‘B flat blues’ from the album Bud Powell in Paris) and Elmo Hope’s solo on St. Elmo’s Fire – also shows a similarity in their approach to left hand comping. All three solos prominently feature what are sometimes called ‘shell’ (i.e. root and 7th voicings), in contrast to the preference of later players such as Wynton Kelly for two, three and four note rootless voicings located closer to middle C.

Just as comparing different versions of a standard can reveal similarities between players of the same period, it can be useful to compare different versions of a single tune by great jazz players from different eras of jazz to gain insights about the differences between periods and the evolution of the music. In his recent memoir Good Things Happen Slowly, pianist Fred Hersch describes one of his early methods of educating himself about jazz. After a less than successful experience in college sitting in with a local jazz group on the tune ‘Autumn Leaves’, Hersch was introduced by a fellow musician to the concept of learning about time through listening to great jazz recordings. Hersch writes that he visited a record store that same week and ‘rifled through the jazz bins, working my way from A to Z, and bought every album that had a version of ‘Autumn Leaves’ on it: records by Miles Davis, Ahmad Jamal, Bill Evans, Oscar Peterson, Erroll Garner, Stan Getz, Chet Baker – thirteen in all. I brought the pile home and played each version of the tune, skipping all the other tracks…it was a revelation. Some were subtle, some were virtuosic, some brisk, some meditative. They all had a mastery of time. I realized each version was unique, and all of them were great.’

If we call Monk, Powell and Hope’s get-togethers ‘a neighborhood hang’, one might say by contrast that Hersch, after doing the jazz hang in his neighborhood, did some ‘hanging with history’. In my view, the ‘neighborhood hang’ (i.e. hanging with other jazz players of the same or similar instrument, interest, age and/or ability) and the ‘history hang’ are both essential for the aspiring jazz musician. One place that both kinds of hanging went on in the mid- to late forties was at the residence of pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams, whose apartment (pictured above) was a gathering place for many of the bright lights of the bebop period. By many accounts, Williams provided important musical knowledge to her visitors, either intentionally or surreptitiously, as in the case of Monk’s borrowing the A section of his tune ‘Rhythm-A-Ning’ from Williams’ tune ‘Walkin’ and Swingin’; Kelley also documents Williams’ influence on Monk’s tunes ‘Criss Cross’ and ‘Hackensack’.

Like ‘Autumn Leaves’, the Irving Berlin tune ‘Blue Skies’ has been reinvented by players and arrangers in many eras of jazz. Mary Lou Williams’ arrangement of the tune for the Duke Ellington Orchestra, recorded between 1946 and 47 as ‘Trumpet No End’ , was one of the pieces that built her reputation as an arranger; Ella Fitzgerald also created one of her better known scat solos on the tune for the 1959 album Get Happy. Thelonious Monk created his tune ‘In Walked Bud’, dedicated to his protégé, by using the chord progression from the A section of ‘Blue Skies’ and adding a different bridge. Monk made well known two studio recordings of his tune; the 1947 original features an interesting chorus split between trumpeter George Taitt and alto saxophonist Shahib Shihab which includes quotes by both players from the Dizzy Gillespie tune ‘Bebop’. (The recording dates of ‘Trumpet No End’ and the original ‘In Walked Bud’ being so close in time suggests that Monk’s choice of the ‘Blue Skies’ progression might have been influenced by his hanging with Williams.) Monk’s version of ‘In Walked Bud’ from the 1968 album Underground features remarkable solos by both Monk and vocalist Jon Hendricks. While Blue Skies has continued to be reininterpreted by historically conscious players such as Bill Charlap, ‘In Walked Bud’ has in turn became a jazz standard in its own right. In recent years it has been reinvented by players including Fred Hersch, Helen Sung (the version linked here is a duo with Ron Carter, but her combo version from the album ‘Going Express’ is also highly recommended) and Kenny Barron.

My tune ‘Monk, Bud and Elmo’ is based on my scale outline for In Walked Bud. It also uses shell voicings, as in the blues solos by Monk, Powell and Hope. Piano players should also learn the scale outline and the original head of ‘In Walked Bud’ in the right hand by memory and combine them with the left hand voicings in the piano arrangement. My tune also can work as a countermelody to ‘In Walked Bud’; it works particularly well to combine ‘Monk, Bud and Elmo’ played by the right hand and/or a treble clef instrument and ‘In Walked Bud’ played by the left hand and/or a bass clef instrument. (The A section of ‘In Walked Bud’, like the bop standards ‘Ornithology’, ‘Anthropology’ and ‘Donna Lee’, is one of those melodic lines that either coincidentally or intentionally works as a countermelody to the tune from which its chord changes originate.)

WOW thank you so much for sharing, cant wait to play it!

I always find that hanging out and playing with other musicians makes me absorb certain parts of their playing, consciously or subconsciously, and make me a more well-rounded player. I’m sure these pianists experienced the same sort of thing, especially when you have a super unconventional playing style like Monk colliding with a more traditional pianist like Bud. I wish it were possible to ask them what they got out of playing with each other respectively, that would really be illuminating.

It was so great to see the old photos of Mary Lou Williams with all of the musicians. I didn’t realize that they were all friends before reading the blog, but I love her arranging and playing. Check out her version of Willow Weep for Me-it is lovely.

I am with Sam A.-I don’t think it matters what your level of musicianship is, you always pick something up from listening to and/or hanging with other musicians. Even if my brain doesn’t totally get what I am hearing at the time I find that things often creep into my playing or singing, and sometimes they even make sense intellectually at a later date.

I can’t wait to try out the right hand melody and scale outline of In Walked Bud with the left hand changes of Monk, Bud and Elmo!