You Are Here is a tune I composed based on the chord changes of the Jerome Kern/Oscar Hammerstein tune ‘All The Things You Are’. (Click the link to hear a recording of the tune by my band Birdcode.) ‘All The Things’ has been recorded by many important jazz players including Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie on ‘Jazz At Massey Hall’ and Keith Jarrett on Standards Volume One. While these are more ‘straight ahead’ versions of the tune like these, the versions Gerry Mulligan and Paul Desmond, Andy Bey and Cuong Vu illustrate the many different ways ‘All The Things You Are’ has inspired jazz players to reinvent the tune.

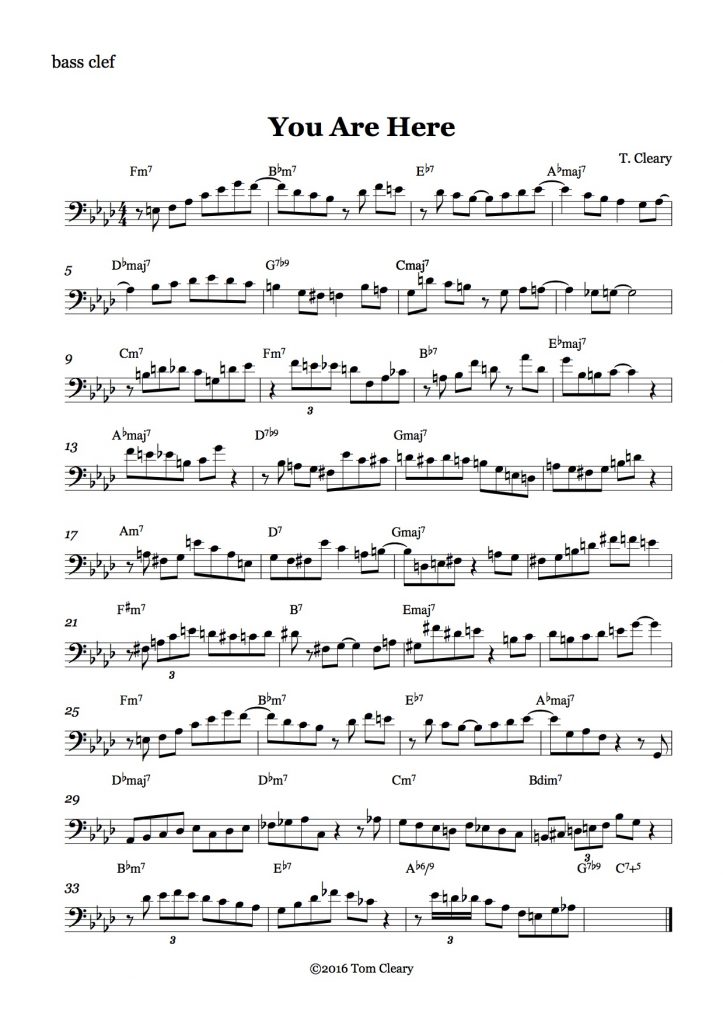

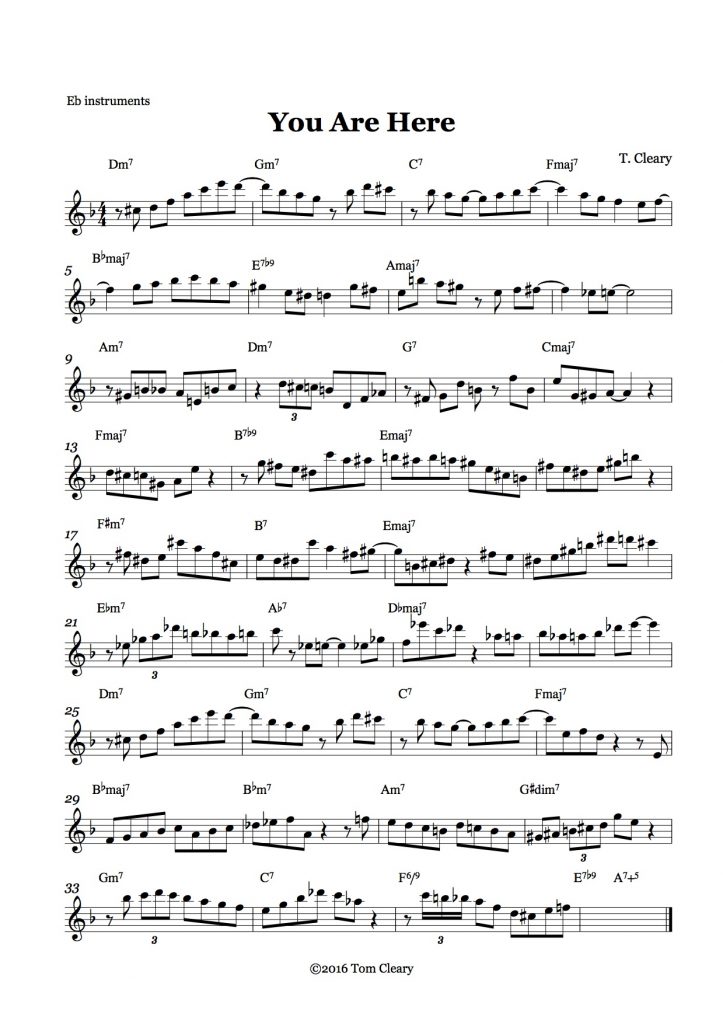

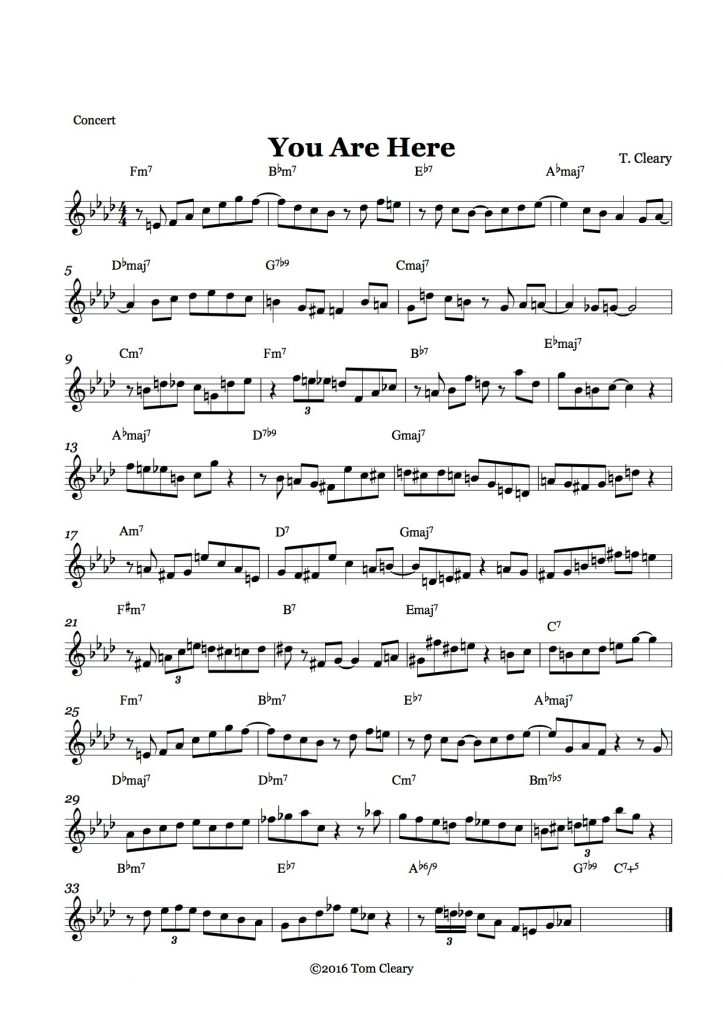

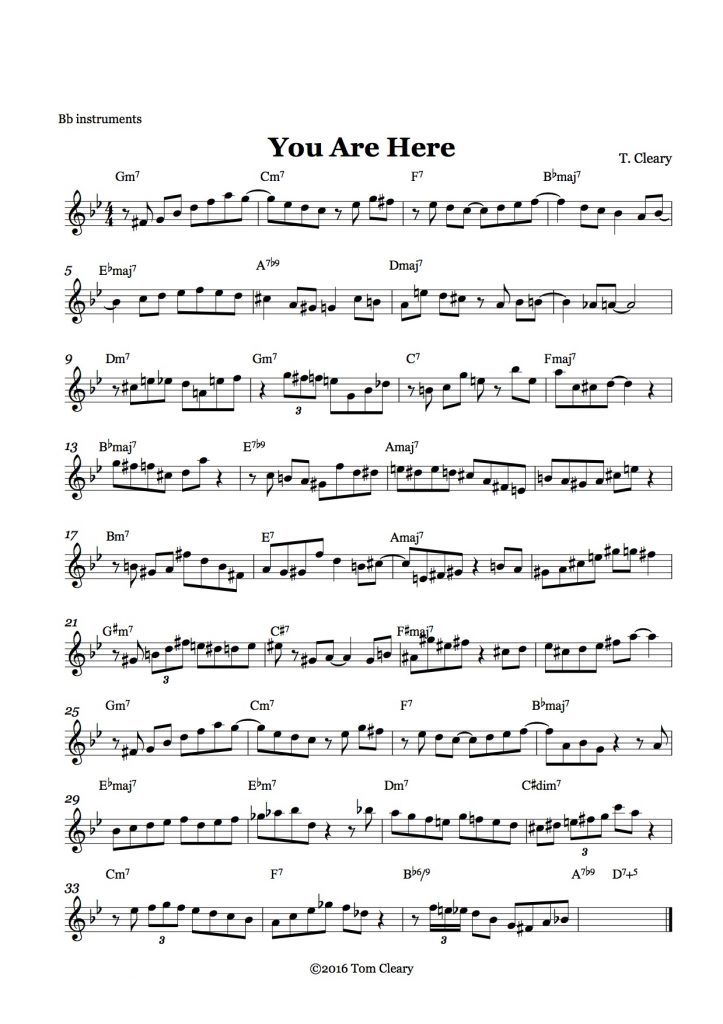

A recording and charts for my tune are below. One of the ways I use this tune is as an etude for players and singers who are working on improvising on ‘All The Things.’ Before one tries to improvise on the chord progression of this tune, it is important to first learn its original melody and chords, as well as a basic scale outline of its chord progression. Click here for a recording of a scale outline which outlines the key areas of the ‘All The Things’ progression (Ab, C, Eb, G and E major) using major scales. (The outline is played on piano with LH voicings but can be transposed an octave lower for other instruments.)

The melodic inspiration for ‘You Are Here’ comes from the compositions and solos of pioneering bebop pianist Bud Powell, who I have listened to since my teenage years and transcribed since my undergraduate years in college. The inspiration for how to construct the tune came from a transcription and analysis by Katharine Cartwright of Ella Fitzgerald’s solo on her version of ‘St. Louis Blues’ from ‘The Birthday Concert – Live In Rome’ . (Cartwright’s work on this solo can be read in the collection Ramblin’ On My Mind.) Cartwright shows how Fitzgerald built the solo almost completely out of quotes from other tunes, including jazz melodies and show tunes. This process, which I think for Fitzgerald was partly preconceived but often spontaneous, is what I would call ‘melody collage’. For players who have studied the original melody and chord progression of a tune like ‘How High The Moon’ but still find it challenging to improvise on, I think that learning to play a melody collage on the same progression (such as Charlie Parker’s ‘Ornithology’, discussed below) and being aware of its sources, or even composing a melody collage of one’s own, can be a helpful in working toward greater fluency and spontaneity. (Fitzgerald mentioned a number of times that she was not naturally disposed toward singing blues tunes, which would suggest that she may have found it challenging to improvise melodically on them as well.)

Cartwright’s work on Ella Fitzgerald led me to analyze Benny Harris’ bop standard ‘Ornithology’ in an earlier blog post and show how Harris’ composed tune, like Fitzgerald’s solo, was assembled from a vocabulary of ‘licks’, but in case of ‘Ornithology’ Harris was drawing all the pieces of his collage from the melodic vocabulary of a single player, Charlie Parker. ‘Ornithology’, like some of Harris’ other lines, is based on the chord changes from an earlier tune (‘How High The Moon’), but also works as a countermelody to that tune. In ‘You Are Here’, I challenged myself to compose a melodic line which, like ‘Ornithology’, is based on a pre-existing set of chord changes (‘All The Things You Are’), uses excerpts from the melodic language of a single player (Bud Powell) and also works as a countermelody to the tune from which its chord changes are borrowed.

This tune can be used as a head (as I do in a short solo piano version of the tune that I recorded ), as a countermelody (as it is in a short solo piano version, where I added an original long-note vocal melody to replace ‘All The Things’), or as an etude that models the use of eighth notes and bebop chromaticism in a solo. I hope that it might lead you to to check out the music of Bud Powell (in this tune I borrowed licks from his tunes ‘Bouncin’ With Bud’ and ‘Dance of The Infidels’ , his solo on ‘Un Poco Loco’ from The Amazing Bud Powell Volume 1, his solos on ‘Cheryl’, ‘Donna Lee‘ and ‘Buzzy‘ from his one studio session with Charlie Parker, and a live version of ‘Ornithology’ for which I studied Ethan Iverson’s transcription in his blog post ‘High Bebop’. The specific page I used is here. Iverson’s series of posts titled ‘Bud Powell Anthology’ are extensive and well worth reading.) I also hope learning ‘You Are Here’ might lead you to use more eighth notes and bop concepts in your improvising, and perhaps to compose your own melody based on ‘All The Things’ changes as a kind of slow-motion practice of the improvising process. There are tunes by a number of great jazz players based on the ‘All The Things’ progression, such as Dexter Gordon’s ‘Boston Bernie’ and Kenny Dorham’s ‘Prince Albert’. These tunes are interesting microcosms of their composers’ improvisational language, and learning them may give you ideas for composing a tune that imitates or contrasts their approach. I hope you’ll also give ‘You Are Here’ a try. I have added charts in transpositions for all common jazz instruments below. Please feel free to share in the comments section any thoughts you have on practicing ‘All The Things’ and/or ‘You Are Here’, as well as other recordings of ‘All The Things’ you find enjoyable and inspiring.

Charlie Parker’s version of this tune is an incredible reimagining of the melodic line. Parker mostly maintains the chords and bassline (save a few new brief chords to recontextualize the original key modulations by Kern), Parker rhythmically and melodically reinvents the original core idea of All the Things you are. To begin, Parker gives us a new introduction based around a D flat minor seventh and a C altered dominant seventh. In the spirit of the frequent modulations Kern supplies, Parker’s intro sets up a dynamic tension between these two chords, which lead to the tune’s first key center, F minor. Parker also expands on the melody in various locations, using descending runs amidst the key modulations. For example, in the eighth bar of the first verse, he uses a descending chromatic run to emphasize the change between the C major and C minor chords. While Parker doesn’t necessarily change the bassline/accompanying chords, he frequently recontextualizes them with these chromatic runs, adding a whole new dimension to this jazz classic.

The version of “All The Things You Are”, by Paul Desmond and Gerry Mulligan has a number of artistic interpretations and deviations from the original standard. The most obvious ones are the double time feel throughout the head and the sparsely played melody. When the solos come in it is evident that the tune is played in 4/4 at a quick tempo, but to my ear the melody sounds like it is played with a 2/4 feel. The melody has also been thinned out by taking a lot of pick up notes before bars out (such as the ones in bars 2, 4, 10, and 12). It has also reduced repetition of single note phrases to whole notes that the original composition utilizes (as in bars 3, 5, 11, 13).

Other differences include the lack of an intro such as the “Bird of Paradise” introduction from the Charlie Parker tune that is often used. The two voices of the saxophones also offer a conversation with each other, with the lower melody answering the higher one, especially on the bridge section. The original tune has just one melody.

This specific version is performed in Ab, the most common key I’ve known this song to be in, although it has been likely performed in every key at some point or another.

Andy Bey’s version of All The Things You Are puts a creative spin on the introduction of this piece by adding scat singing before the original melody. His voice acts as an instrument leading into the solo melody. He only begins the actual lyrics on measure 17, and when singing the melody changes the rhythm to a more fast paced, quickly worded song.