This series of blog posts is titled ‘Harmonic Moss’ as it deals with rootless chord voicings, and moss is sometimes referred to as a rootless plant. This is not the first time I’ve come across moss in reference to music; during my time in bassist Mike Gordon’s band, I appeared on a compilation called ‘Moss: The Remixes’ (downloadable for free from LivePhish.com), where an extended remix of his tune ‘The Void’ includes an improvised solo I played on a celeste to the accompaniment of percussionist Tim Sharbaugh beating polyrhythmically on Mike’s propane tank. (The celeste is the bell-like keyboard instrument that was played on ‘Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood’ by his resident jazz pianist Johnny Costa, and by Thelonious Monk at the opening of ‘Pannonica’ on Monk’s Music.) This was one of many musical vortexes I happily explored while working with Mike. My efforts to nudge the band in a jazz direction can be heard on a live recording of the band in Vancouver from 2014, where (within a version of the tune ‘Susskind Hotel’) we perform my arrangement of the early jazz standard ‘I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate’. A tour guide at the Louis Armstrong House Museum recently reminded me that this tune, often credited to other composers, is an Armstrong composition.

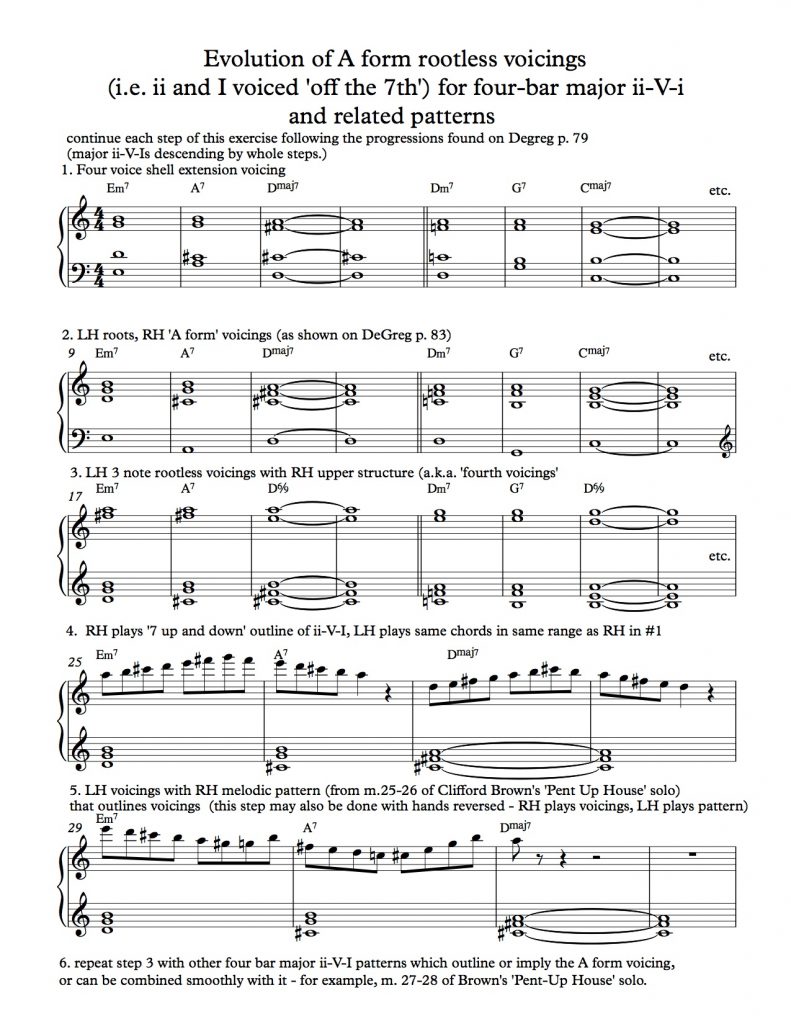

The sheet below shows an evolution of the ii-V-I progression from (in #1) a two-handed expansion of root position (which Phil Degreg calls ‘four voice shell extension’ and one of my students more succinctly calls ‘split voicings’), to (in #2) the rootless voicing which places the root in the left hand and the rest of the chord tones in the right, to (in #3) the ‘fourth voicing’ which combines the rootless voicing in the left hand with upper structure notes in the right, to various single note patterns in #4, 5 and 6 that combine the left hand rootless voicing with scales and melodic shapes. An important project is to take tunes you learned with chords in root position, such as the tunes in the Root Systems posts, and learn to comp through their progressions in the style of the #2 example shown here, and play right hand melody up the octave with rootless left hand changes as shown in #4 and 5.

The melodic pattern shown in the third section of the sheet below is only one example of many patterns related to the ‘A form’ voicing of the ii-V-I progression. When I practice a lick through all twelve keys, I find it valuable to associate it with a chord voicing. In my experience practicing and performing jazz, the process of associating a pattern with a voicing is a subjective one, so I am not suggesting that any given melodic pattern has only one voicing with which it can be associated. I am rather suggesting that, if you want to practice a melodic pattern in one hand through all keys, it is helpful to find a chord voicing that you can see and/or hear as having a conceptual connection with that pattern, and then practice the voicing and the pattern together through all keys. The goal of this kind of practice is to make it possible to use the pattern in combination with any other voicing or without a voicing. Although some jazz educators warn against practicing licks, I think that taking a lick through all twelve keys is a valuable exercise, whether or not the lick becomes consciously or unconsciously integrated into your melodic vocabulary.