In hopes of shedding some light on the difficult balancing act of jazz comping, I have transcribed the work of two great jazz pianists who were also great accompanists (or ‘compers’.) Among other things, these comping parts by Sonny Clark and Oscar Peterson demonstrate how a great jazz pianist uses a chord progression like a great interviewer uses a set of questions. As I was transcribing these comping parts and the solos they accompany, and adding commentary on the interplay between soloists and accompanists to these transcriptions, I found myself awestruck by the level of split-second interplay between these great players. I was also aware how my commentary could come off like the great Peter Schickele routine where he follows Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with play-by-play sports commentary. In any case, I hope these transcriptions are helpful to players who seek to improve their responsiveness and creativity as compers or soloists.

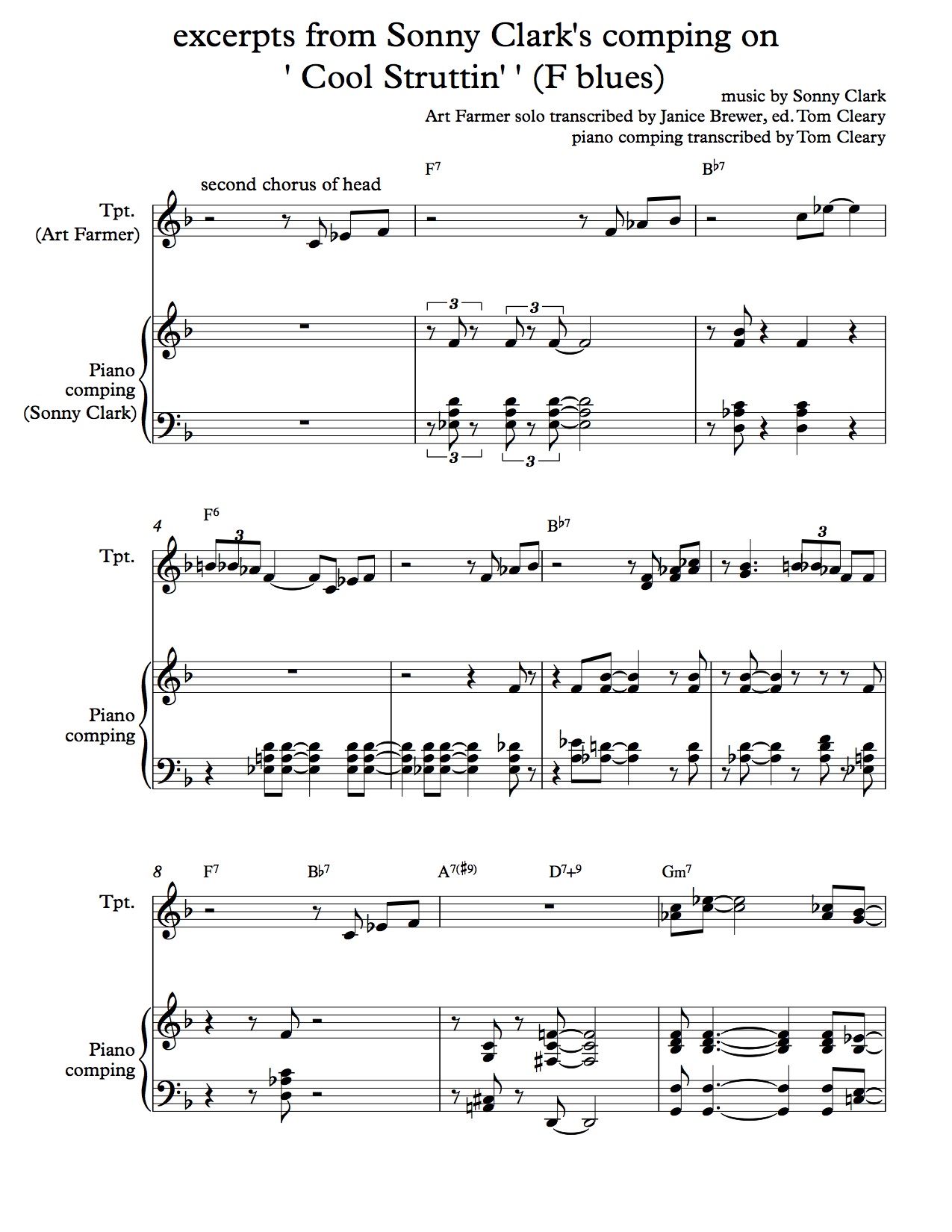

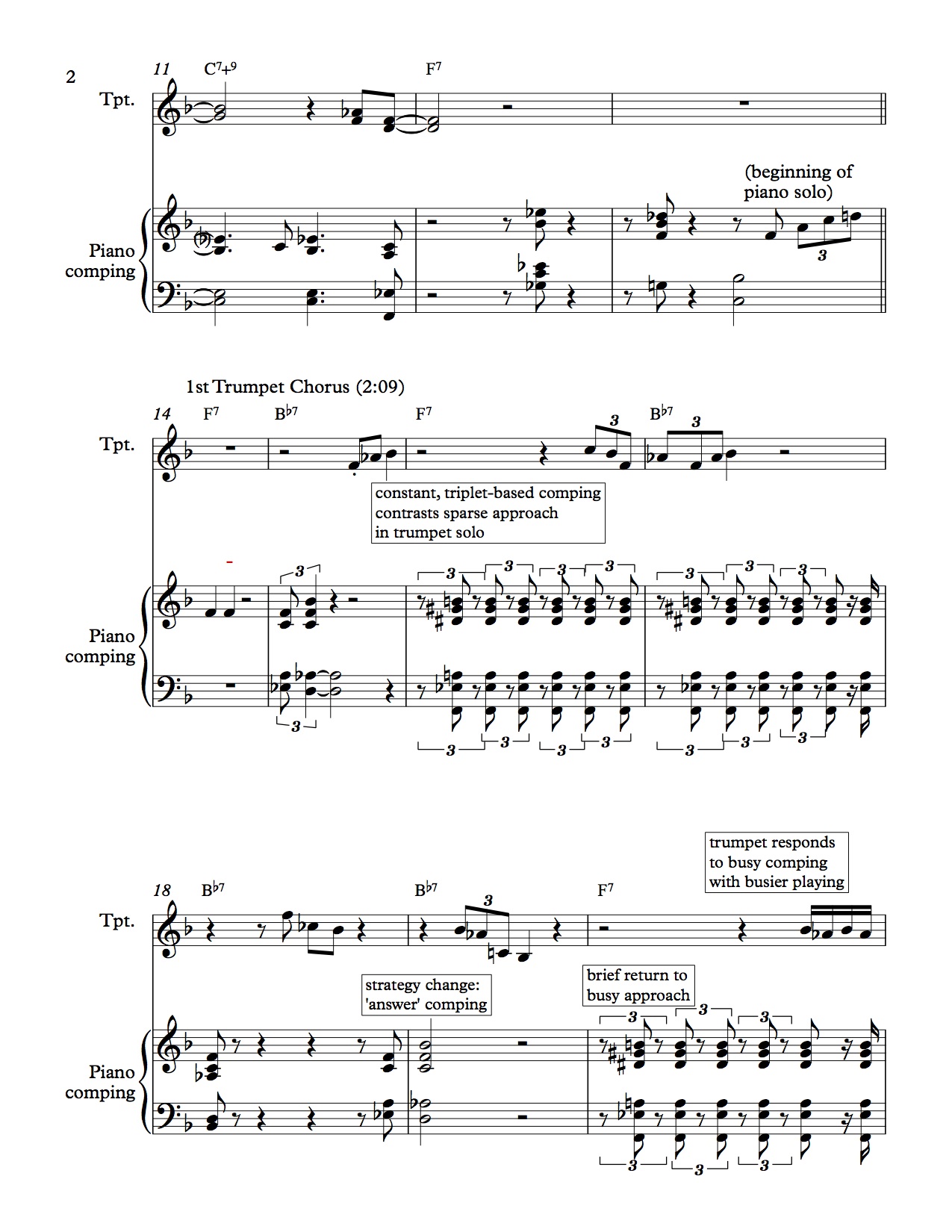

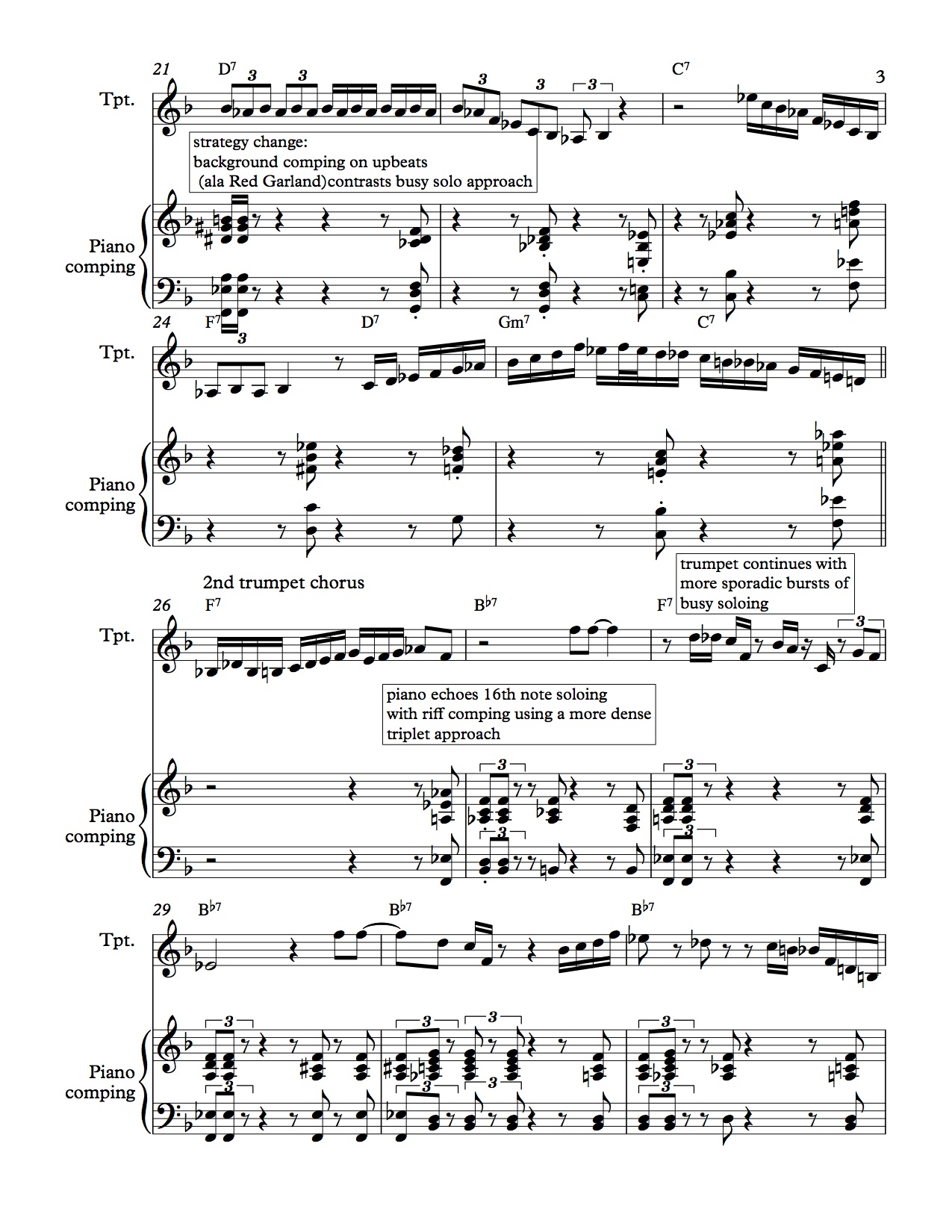

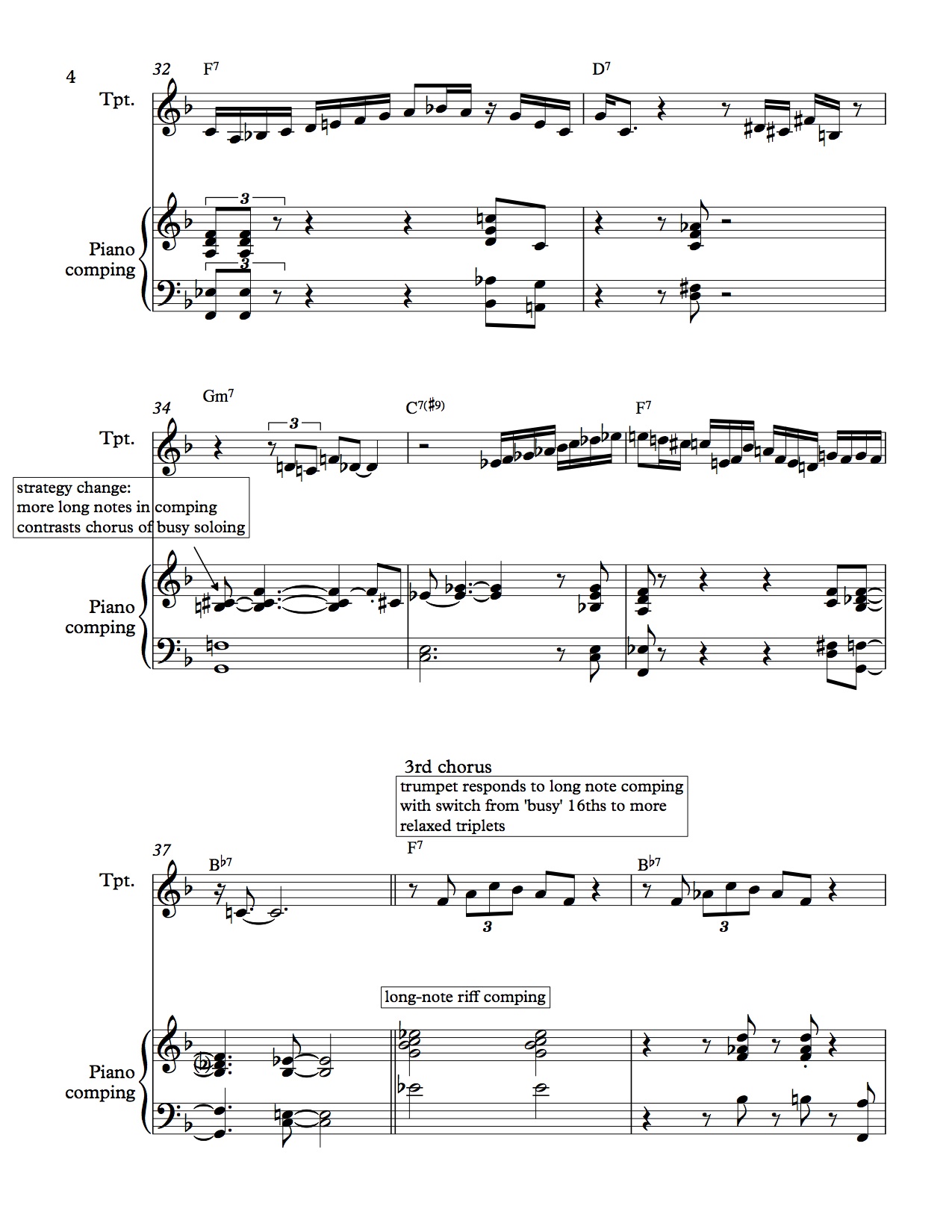

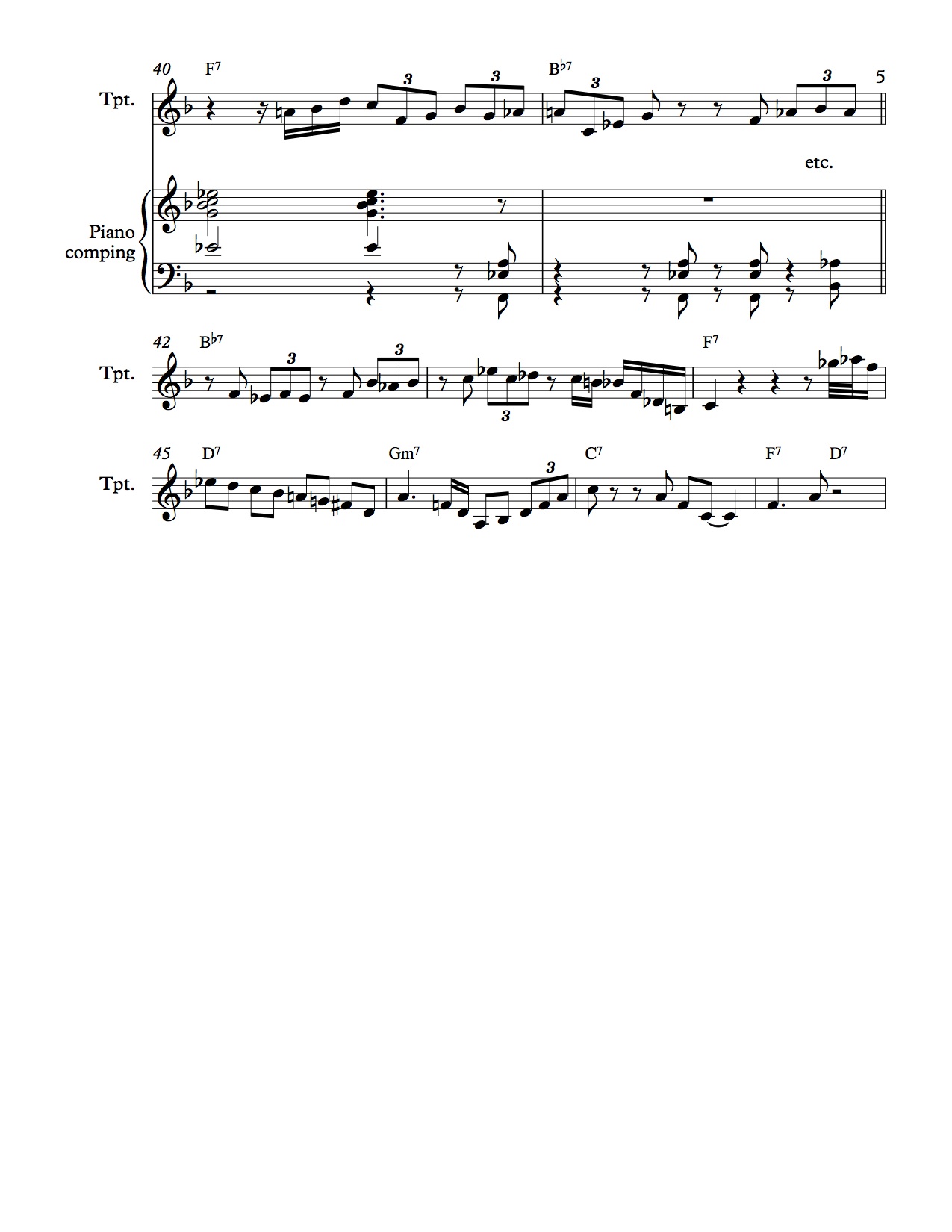

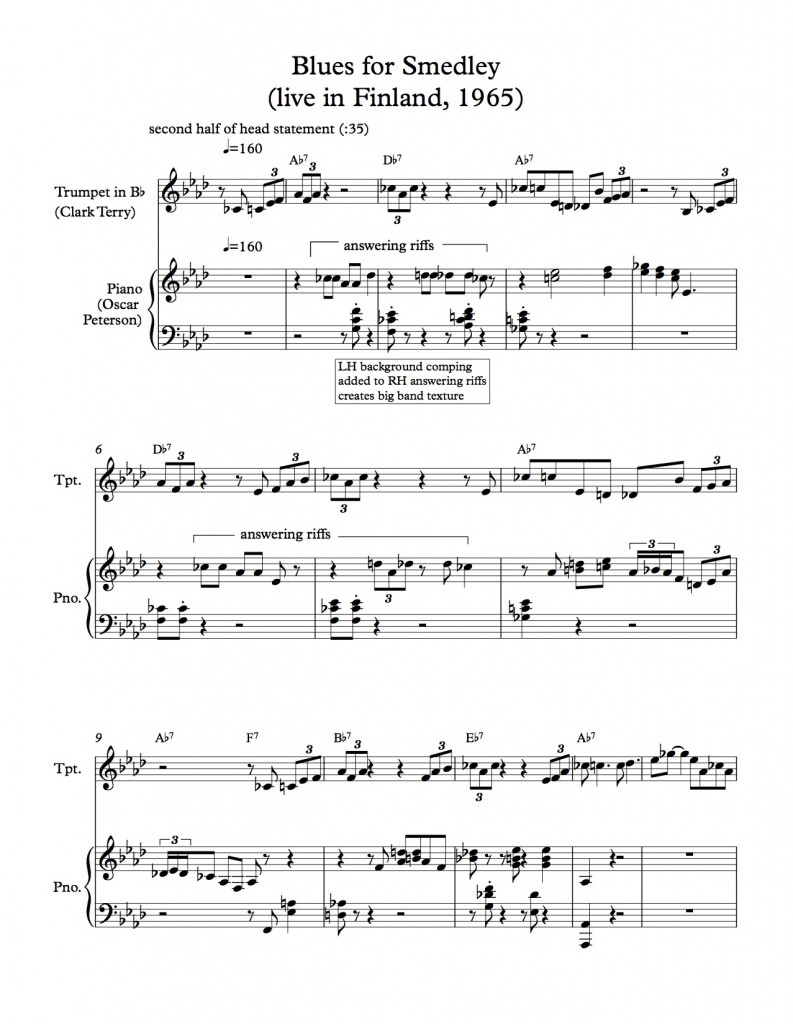

As I transcribed these choruses from ‘Cool Struttin’ (from the Sonny Clark album of the same name) and a video of a live performance by Peterson and Clark Terry of ‘Blues for Smedley’, I was reminded of how pianists who are skilled at comping create contrasts within their own parts in a variety of ways, for example, changing from more busy comping to more sparse comping, or from comping that is more melodically static to comping which is more melodically active. In my analysis here, I call these ‘strategy changes’. In the examples shown here, Oscar Peterson and Sonny Clark change their strategy often, sometimes in response to activity in the soloist’s line, and other times to break with a comping pattern before it becomes undesirably repetitive. In both tunes the piano part doesn’t stay with a single comping approach for a whole chorus of the form, but rather tends to change every two to four bars.

Skilled compers are also able to alternate during a single solo between echoing the soloist’s ideas at some points and contrasting their ideas at other points. At a number of points in ‘Cool Struttin’ and ‘Blues For Smedley’, to my ear, both these kinds of responsive comping lead the soloist to change their strategy, either to further develop the idea being echoed in the comping (as in Art Farmer’s second chorus on ‘Cool Struttin’) or to pick up the contrasting idea being introduced in the comping (as at the beginning of Clark Terry’s third chorus on ‘Blues for Smedley’). This underlines how important it is for pianists to use strong ideas in comping, to either clearly echo the soloist’s idea or to create clear contrast with the soloist.

In the examples below, both Sonny Clark and Oscar Peterson both use what I call ‘riff comping’, which uses repeating and usually simple melodic patterns either to fill spaces in the melody (which I call answering riffs) or as a counterpoint to the melodic line (which I call background riffs). Although both the examples given here are in small group contexts, both Sonny Clark and Oscar Peterson’s uses of riff comping echoes the use of horn section riffs in classic big band blues arrangements such as ‘C Jam Blues’ and ‘Blues in Frankie’s Flat’. The examples here also include comping which is not connected to a repeating pattern but is rather a spontaneous response to activity in the solo line; I call these answer comping. Sonny Clark’s comping during the head statement of his tune ‘Cool Struttin’ includes answer comping, and then he begins to use riff comping in the second chorus of Art Farmer’s solo. Oscar Peterson begins comping behind Clark Terry’s head statement on ‘Blues for Smedley’ using riffs that sound like the composed riffs in a big band arrangement, but quickly changes to an improvised background line in his right hand. Starting with the first chorus of Terry’s solo, he returns to more ensemble-style riff comping.

I encourage readers to listen to the recordings of the tunes while following my transcriptions and comments. I encourage you to use the comment section to add to or even disagree with my play-by-play commentary. For pianists seeking to increase the variety of their comping, I would suggest learning the transcribed comping parts and playing them along with the original recording. Keep in mind that the ultimate goal here is not to memorize the transcriptions, or even to emulate Peterson’s virtuosity or Clark’s harmonic sophistication, but rather to strive toward their level of variety and responsiveness. My hope is that those who read this blog post and study these transcriptions can borrow ideas from Oscar Peterson and Sonny Clark and combine them with their own ideas to work toward a personal approach to creative and responsive comping.

I’d also encourage comments that answer the following question (required for my jazz piano students): Name a jazz recording involving piano and one other solo instrument and identify one or more specific moments in which chordal comping (on piano or guitar) influences the development of an improvised instrumental or vocal solo by another player (or where the development of the solo influences the comping). If possible, add a link to a public page (YouTube, etc.) where the recording can be heard; use timings (i.e. ‘2:35’, ‘4:17’ etc.) to identify the moments of soloist-accompanist interplay, and give a brief description of what happens. (Examples of chordal accompaniment to a solo instrument in other styles are acceptable as well, provided that both parts have some improvisational element to them.)

Oscar Peterson Trio with Clark Terry – Blues for Smedley, live in Finland 1965

Cool Struttin’ – Sonny Clark (Art Farmer, trumpet)

Here’s a nice example of a pianist responding to the melody of a tune: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GoYAGNLqFwg

Tyner’s regular comping grows and shrinks to fill the gaps in the melody during the head, staying low during Coltrane’s phrases and expanding during the breaks. There are also a number of examples when Tyner’s comping finds the note or phrase that Coltrane has just played (for example, at 1:40). Finally, Tyner’s comping for himself becomes much more sparse as Elvin Jones jumps into double-time and begins to fill more sound around 1:47.

Great example, Adam, and great work describing Tyner’s accompaniment of Coltrane and himself. ‘Soul Eyes’ is a great tune and probably Mal Waldron’s best known composition, but your link reminded me he was a prolific composer and has many other great tunes (‘Fire Waltz’, which is on his record ‘The Quest’ as well as the Albert Tootie Heath/Ethan Iverson album ‘Tootie’s Tempo’, and ‘Nervous’ which is on the soundtrack from the TV broadcast ‘The Sound of Jazz’, are two of my favorites.) Coltrane’s version of ‘Soul Eyes’ also goes on a list for me of great examples of interpretations of standards where the soloist plays the melody and then gives the next chorus to the pianist. Miles’ original version of ‘My Funny Valentine’ with Red Garland and the original ‘Someday My Prince Will Come’ with Wynton Kelly are two others, and both feature the kind of comping transition you describe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MItUBCFgWD8

In this tune, the intensity of Hugh Lawson’s comping changes in order to complement the solos of Lateef. When Lateef plays a flourish of melody, Lawson backs off, but his comping becomes more prominent when Lateef is between phrases. (2:30)

Algiers by Austin Peralta – Selections @ 5:13-5:20, 5:38-6:05

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DipaQNHewXw

5:13-5:20

Amidst the bass groove and some saxophone stylings, the piano accompanist jumps in with a sequence of two connected 16th notes followed by 5 8th notes played with staccato. The rhythm–melody, which features a walking riff that ascends up from G and back down. Shortly after, the saxophone soloist repeats the riff, changing the tones on the 3rd and 4th notes, before returning back to his or her original stylings.

5:38-6:05

After some period staying behind the melody, the piano accompanist comes forth with a “strategy change” and begins to play an arpeggio. The arpeggio is pretty loose, and seemingly features three notes descending from A sharp. However, in listening closer, we find the arpeggio only features two notes–A to A sharp ascending–though the piano player continues to play chords in a freestyle rhythm below and above the pitch of the arpeggio. The saxophone soon joins in on the arpeggio, following the piano rhythmically and melodically for the rest of the fifth minute of the song. The saxophone almost attains a muted trumpet-like quality, the sound reminiscent of Al Hirt’s classic, The Green Hornet.

Your detailed commentary shows that you have done some close listening to this modal, vamp-based piece. I wasn’t previously familiar with Austin Peralta’s playing, but in checking out some of the music from his debut album with Ron Carter, I noticed that like many other great jazz pianists who gravitate toward more harmonically open and exploratory playing (Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Hiromi and Robert Glasper, to name a few), Peralta began his work as an improviser by focusing on some standard short-form harmonic structures, such as ‘Someday My Prince Will Come’, Coltrane’s ‘Naima’ and Chick’s ‘Spain’. It is unfortunate for the jazz community that he did not live long enough for us to hear his musical conception evolve further, although he evidently left behind a considerable and virtuosic body of work.