In a 2013 interview with Charlie Rose, Yankee pitcher and five time World Series champion Mariano Rivera was asked how he prepares to face a particularly difficult hitter:

Rose: Tell me about studying for a hitter. How do you study a hitter?

Rivera: Oh, we have so much videos, so much reports…

Rose: and what do you get out of that video?

Rivera: For me, I just learn about the experience. I watch the game, exactly the game that we’re playing. If the guy’s hot, well, pay attention to the game…I’m seeing the game while I’m doing something to get ready.

Rivera’s use of the word ‘hot’ to describe a highly skilled hitter who he studies on video in preparation for a real-time confrontation reminds me of how jazz musicians use the same word to describe a highly creative improviser. A ‘hot‘ player is someone bandleaders want to feature, who colleagues are eager to perform with, and who aspiring players may want to study through recordings, as a way of assimilating their ideas. Rivera’s description of using videos to prepare for a game sounds not unlike a practice ritual which is common for jazz players at many levels, the practice of learning recorded solos by master players, either by notating them or simply learning them by ear. Perhaps the most famous account of one great jazz player learning from another is the story of Charlie Parker at an early point in his career studying the records of Lester Young. Here is the story as told by the bassist Gene Ramey (quoted in Carl Woideck, Charlie Parker: His Life and Music): ‘In the summer of 1937, Bird underwent a radical change musically. He got a job with a little band led by a singer…they played at country resorts in the mountains. Charlie took with him all the Count Basie records with Lester Young solos on them and learned Lester cold, note for note…when he came back, only two or three months, later, the difference was unbelievable’.

Part of Parker’s mystique was that, rather than actually performing Lester Young’s solos, he incorporated older player’s concepts into an improvisational language all his own. However, as Charles Mingus relates in his essay ‘What Is A Jazz Composer?’, it was something of a tradition among the older players of the swing era for great recorded solos to be played note-for-note in live performances, sometimes by the players who had originated them. Mingus communicates a level of respect for this tradition, even to the point of questioning younger players’ ability to ‘repeat anything at all’:

‘When I was a kid and Coleman Hawkins played a solo or Illinois Jacquet created [his tenor sax solo on] “Flyin’ Home,” they (and all the musicians) memorized their solos and played them back for the audience, because the audience had heard them on records. Today I question whether most musicians can even repeat their solos after they’ve played them once on record. In classical music, for example people go to hear Janos Starker play Kodaly. They don’t go to hear him improvise a Kodaly, they go to hear how he played it on record and how it was written. Jazz was at one time the same way. You played your ad lib solo, you created it, and if it was worthwhile, then you played it in front of the public again…Today, things are at the other extreme. Everything is supposed to be invented, the guys never repeat anything at all and probably couldn’t. They don’t even write down their own tunes, they just make them up as they sit on the bandstand. It’s all right, I don’t question it. I know and hear what they are doing. But the validity remains to be seen -what comes, what is left, after you hear the melody and after you hear the solo.’ (The ellipsis represents a transition I’ve made to an earlier section of the essay, which I read as a response to the section I quoted first.)

Mingus seems to be referring to a tradition of improvised solos from recordings being performed more or less exactly as they were recorded, ‘because the audience had heard them on record’ and wanted to hear them the same way again. This might be called ‘the literal approach’ to performing recorded solos. In his book Creative Jazz Improvisation, which has with good reason become a standard jazz education text, Scott Reeves writes that ‘transcribing and practicing improvised solos by master jazz musicians helps the student of improvisation assimilate the vocabulary and style of these artists in much the same way that children learn to speak by imitating their parents’. One possible interpretation of Reeves’ parent-child metaphor, and Gene Ramey’s Charlie Parker story, is that improvisers in earlier stages of development learn recorded solos and abandon this practice in their mature years – although the profusion of mature improvisers such as Ethan Iverson and James Mahone who publish their transcriptions on the internet suggests otherwise. Reeves also mentions three ways a solo can be learned (by learning it aurally, by writing it down, and by learning it from a published transcription) and adds: ‘After practicing a transcription, create your own improvisation on the tune, incorporating elements of the artist’s style.‘ This reflects a fairly common view through the jazz education world that learning improvised solos from recordings is an early stage in a player’s artistic development. Reeves’ comment suggests a two-step process, where the literal approach to performing a recorded solo leads directly to a spontaneous and original improvised solo.

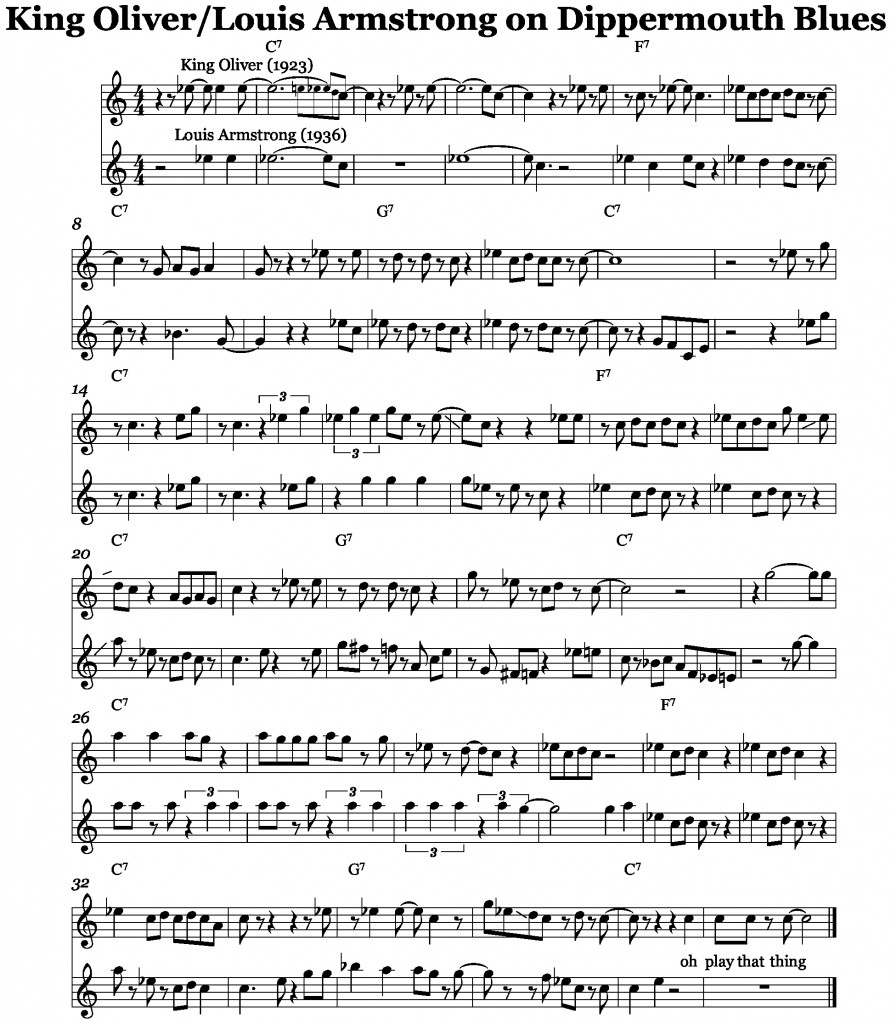

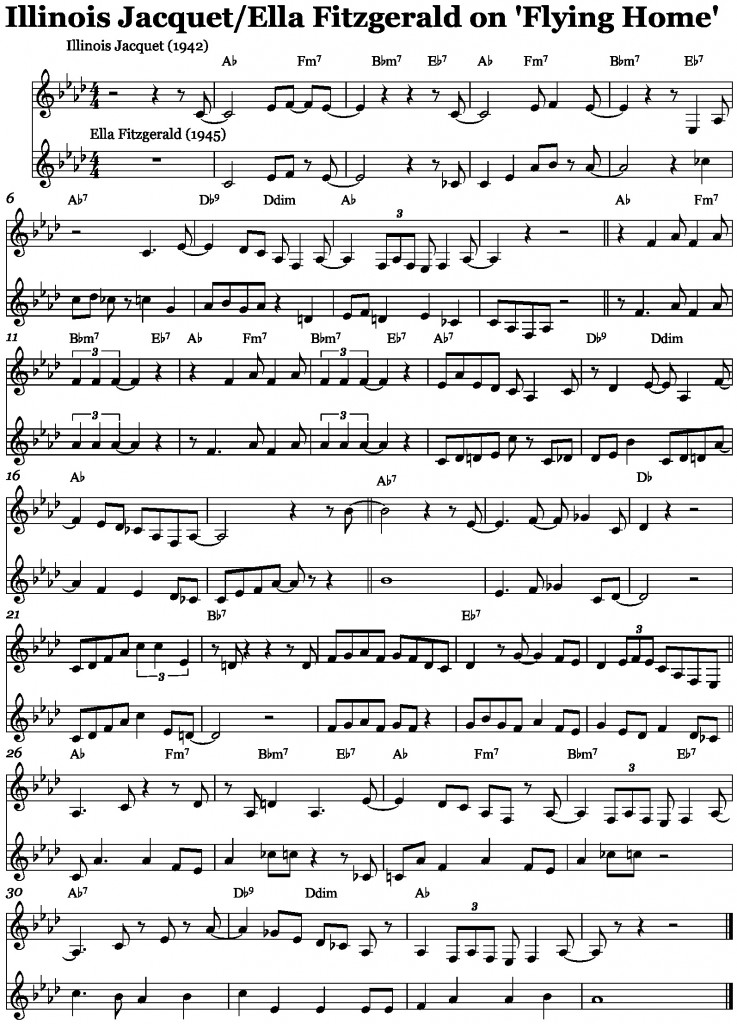

This eminently logical view is supported by a number of recorded examples where literal performances of transcribed solos have a mechanical quality and lack the spontaneity of the original version. For me, some of the music of the 1970s group Supersax, and the Lambert, Hendricks and Ross album ‘Sing A Song of Basie’, where they perform Count Basie Orchestra arrangements complete with their original solos and no new improvisation, falls into this category. However, there is also a tradition, less well documented in the literature of jazz education, of great improvisers in their prime years re-creating existing solos with an attitude of simultaneously challenging and revering the original. In both Louis Armstrong’s 1938 re-creation of King Oliver’s 1923 ‘Dippermouth Blues‘ solo, and Ella Fitzgerald’s 1945 re-creation of Illinois Jacquet’s 1942 ‘Flying Home‘ solo, we can see one jazz master’s deep admiration for another’s achievement expressed through a deeply imaginative revision of the earlier solo. The fact that Fitzgerald and Armstrong recorded these tunes fairly early in their century-spanning careers suggests that taking the revisionist approach to performing a recorded solo might be a developmental stage between literal imitation and more spontaneous originality.

The soundtrack to the TV series Boardwalk Empire includes a performance by Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks of the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra tune ‘Sugarfoot Stomp’. The original 1925 Henderson version of ‘Sugarfoot’ featured a young Louis Armstrong and was an early re-working of ‘Dippermouth Blues’, which Armstrong had recorded with King Oliver in 1923. In ‘Sugarfoot’, Armstrong re-created Oliver’s original trumpet solo from ‘Dippermouth’ with a number of revisions, including taking a high A that Oliver had played briefly near the end of the solo and making it a long, sustained note that demonstrated Armstrong’s prodigious range. Armstrong continued to respectfully and ingeniously revise Oliver’s solo in a version of ‘Dippermouth’ with his big band in 1936. Although Armstrong’s revisions in many ways demonstrated the strides that he had made in his playing beyond the technique of his former employer Oliver, Armstrong also chose not to try and imitate Oliver’s use of the mute, and so he was in a sense adapting the solo to a different instrument, the straight (unmuted) horn. (The choice was not without deliberation: in Terry Teachout’s Pops, Armstrong’s first wife Lil is quoted saying that Armstrong ‘spend a whole week trying without success to imitate Oliver’s ‘wah-wah’ muted inflections on ‘Dipper Mouth Blues’.) It was perhaps this ‘handicap’ that Armstrong gave himself which prompted some of his imaginative additions to the solo. When laid horizontally next to Oliver’s solo, Armstrong’s 1936 ‘Dippermouth’ solo, besides changing the long ‘A’ from ‘Sugarfoot’ to a series of repeated high notes (a move that was becoming one of his trademarks), Armstrong also makes ingenious use of filling the pauses Oliver left with eighth note movement that was highly modern for its time and exhibits the chromaticism which would later be associated with the bebop movement. (While most audio files of the King Oliver ‘Dippermouth’ sound like the tune is in the key of B, my guess is the key has been lowered by the age of the recording, so I have transposed his solo to C, the key of Armstrong’s ‘Dippermouth’ version of 1936. The small notes at the beginning of the Oliver solo are meant to show the range over which he bends the initial note through embouchure and mute.)

In her version of ‘Flying Home’ from 1945, Ella Fitzgerald re-creates the iconic Illinois Jacquet solo from the original Lionel Hampton recording that Mingus refers to in his essay. Fitzgerald’s ‘Flying Home’ solo indicates her close study of bebop melodic concepts, particularly through the way that she introduces more eighth note motion than the original, more chromaticism, and more use of upper chord tones such as the ninth and thirteenth. Fitzgerald’s ‘Flying Home’ also exhibits her ability to deftly incorporate quotes into her improvising; she concludes the chorus here with ‘Merrily We Roll Along’, but a later section of the solo also uses ‘Yankee Doodle’. (Fitzgerald’s version seems to be in the key of G, but I have transposed it to A flat, the key of the original version by the Lionel Hampton band.)

Armstrong’s revisions to the ‘Dippermouth’ could arguably be called improvements and are in line with his many recorded quotes where he openly admits his technique was superior to Oliver’s. However, Armstrong’s revisions of Oliver’s ‘Dippermouth’ solo show clear respect for the man Armstrong called ‘my hero and my idol’ by clearly preserving the outlines of Oliver’s phrases. Fitzgerald, on the other hand, alternates throughout the chorus shown here between playing four bars of Jacquet’s solo and introducing four bars of her own very different and bop-influenced ideas – an approach which suggests that her desire to challenge Jacquet was perhaps equal to her desire to honor him.

Sonny Stitt’s versions from 1958 and 1963 of Charlie Parker’s ‘Koko’ solo from 1945 shows how the tradition of performing classic recorded solos continued into the later years of the bebop period. (There is an argument to be made that we are still, in some senses, in that era today.) In much the way that Fitzgerald simultaneously recalls and updates Jacquet’s, one can hear Stitt thoughout his longer solo constantly weaving his own phrases in between those of Parker, as well as personalizing the Parker phrases.

Between Stitt’s versions of Koko, Sonny Rollins began his solo on a live version of Lady Bird in 1959 with two choruses of Charlie Parker’s solo from the recording of Half Nelson with Miles Davis where Parker plays tenor. In his book Thinking In Jazz, Paul Berliner points out that Parker made a similar kind of tribute to Armstrong in his solo on the 1949 recording of his blues Cheryl, where he quotes seven measures of Armstrong’s intro solo on West End Blues.

Dexter Gordon made an homage to Parker on The Jumpin’ Blues, a tune on an album of the same name recorded in August of 1970 (which contains pianist Wynton Kelly’s last solos on record before his death in 1971). The original version of ‘The Jumpin’ Blues’ was recorded by The Jay McShann Orchestra in 1942 and contained one of Parker’s first recorded solos. Gordon’s solo on his 1970 version begins with a quote of the first three measures of Parker’s solo, which then becomes a motive that Gordon develops through his first chorus.

As the availability of transcribed solos proliferates, the number of questions about how they should be used increases as well. Should transcribed solos be used only as an exercise for aspiring players? Is the process of creatively adapting an existing solo by a jazz master a valuable process for improvisers at all ability levels, or is it a task at which only the most proficient players can succeed? Is the proliferation of notated solos in books and on the internet endangering the process of learning solos by ear, as Armstrong, Fitzgerald and Stitt almost certainly did? Is it still possible to take a creative revisionary approach to performing solos by jazz masters, as Armstrong, Fitzgerald and Stitt did? I encourage anyone reading this entry to respond in the comment section with their thoughts on these or any other related questions.

Was just learning about some of this on Performance Today, their story about Keith Jarret. Yay for more reading in a lateral direction.

http://performancetoday.publicradio.org/display/programs/2014/02/05/

As you note, Mingus wrote that “the validity remains to be seen” re recreating recorded solos. The technology for mass dissemination of recordings created a necessity of repetition – so that audiences could hear the same desired thing time and time again. This preference for repetition is essentially infantile, and is one underlying reason for the gradual displacement of live music by disc jockeys.

Recordings made it possible for musicians to imitate themselves and others. Hitherto, a more select group of musicians had the kind of musical memory that would permit this.

I think the view of Mingus is more adequately expressed by his tune title: “If Charlie Parker were a Gunslinger, There’d be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats”.

Thanks for the comment. I agree with you that a preference for hearing a song repeated exactly, with solos that were originally improvised re-created down to the last detail, suggests a listener who doesn’t realize how a performance fully located in the present is more real and inspiring than one which seeks to re-create the past. I think this preference is particularly prevalent in rock listeners, including those who follow the modern-day incarnations of long-running bands. I think of a quote from Derek Trucks, who said that when he plays with the Allman Brothers, ‘people look at [him]…like [he’s] burning the flag’ if he strays too far from the original Duane Allman guitar parts. The way I read Mingus’ essay, however, is that he was questioning the validity of the players who he says ‘never repeat anything at all and probably couldn’t’ and ‘don’t even write down their own tunes, they just make them up as they sit on the bandstand’. It sounds to me like in this essay he is asserting the values of an era of jazz which contrasts today’s fetish for exact repetition, an era in which re-creating and transforming existing solos in performance (rather than repeating them exactly) was a way to display respect for great players. The examples I cite of Armstrong, Fitzgerald and Stitt re-creating solos of their predecessors and contemporaries, and improving them in the process, makes me wonder whether jazz education sometimes does students a disservice by setting up a false choice between exact repetition of existing solos and completely original improvising. One thing I’ve learned through my experience of playing jazz is that there is no way for the performance of a transcribed solo to be exact – and that’s a good thing. I have certainly picked up the vibe from many great players that repeating a solo exactly is a disservice to those one plays with and to the player from whom one is borrowing. But I have also learned that much of the greatest improvising involves copious use of a common melodic language, and that leads me to wonder whether there is a way to show one’s respect for a great solo by keeping it in the furnace (or compost pile) of one’s improvising repertoire, rather than just the ‘cold storage’ of recordings and transcription.

I think this is a very good take on learning solos and how they are incorporated into performance. I very much do agree with the sentiment that not playing a solo verbatim and rather using it as influence for your own solo is the way to go.