This past Sunday, on the NBC show ‘Meet The Press’, I watched a skilled TV journalist, David Gregory, interviewing a seasoned politician, Senator John McCain. Whatever one thinks of the style or viewpoint of these men, I think it is safe to say that they are among the most accomplished and skilled practitioners of their respective professions. A one-on-one interview involving both of them is as good an opportunity as any to see the most typical techniques in political dialogue today. So I had to breathe a sigh of regret when I saw them engage in an unfortunate practice which is increasingly common in modern politics: the moment when a previously courteous dialogue breaks down and two intelligent but frustrated people begin talking over one another. As an improvising musician, I had to wonder: have these guys ever learned to trade fours?

Jazz improvisation is often explained as a largely individual pursuit, the nomadic voyage of the ingenious and fearless soloist (Parker, Coltrane) across a forbidding and often self-designed landscape of musical challenges (Confirmation, Giant Steps, Rhythm Changes) accompanied only by a small band of hardy accompanists who don’t attract or merit much attention beyond their association with the leader. This version of history bypasses the fact that these towering figures, so well known for their mastery of what might be called the ‘accompanied monologue’ (i.e., melody statements, full-chorus and multiple-chorus solos), were equally gifted at the form of musical conversation known as ‘trading fours’, where two or more musicians exchange phrases over the form of a song. If transcribing the full chorus solos of great improvisers can help us learn their melodic language and their approaches to developing ideas and building energy, perhaps studying the situations in which these players traded fours (and twos and eights) can tell us something about how deeply they listened to their musical cohorts and how quickly they could assimilate the ideas of others into their own playing.

Lester Young, Ella Fitzgerald and Sonny Stitt, to name three giants, all improvised awe-inspiring extended solos, but the gift for musical oratory that they showed in them is only part of their greatness as players. All three of them also had the ability to turn right around after their musical monologues and trade fours with the same inspiration and sense of swing that they put into their solos. Often it’s plain to hear that the ‘trading fours’ sections, coming as they did after the individual solos, took the whole performance to a new level of intensity. It is crucial to remember this today, when it easier than ever for budding improvisers, like the participants on ‘American Idol’, to develop soloist skills without becoming aware of how communicating with your accompanists and fellow musicians is crucial to the success of any soloist’s performance. All three of the soloists I mentioned above knew this, and recognized it to the extent that their recorded performances spend substantial time on trading fours.

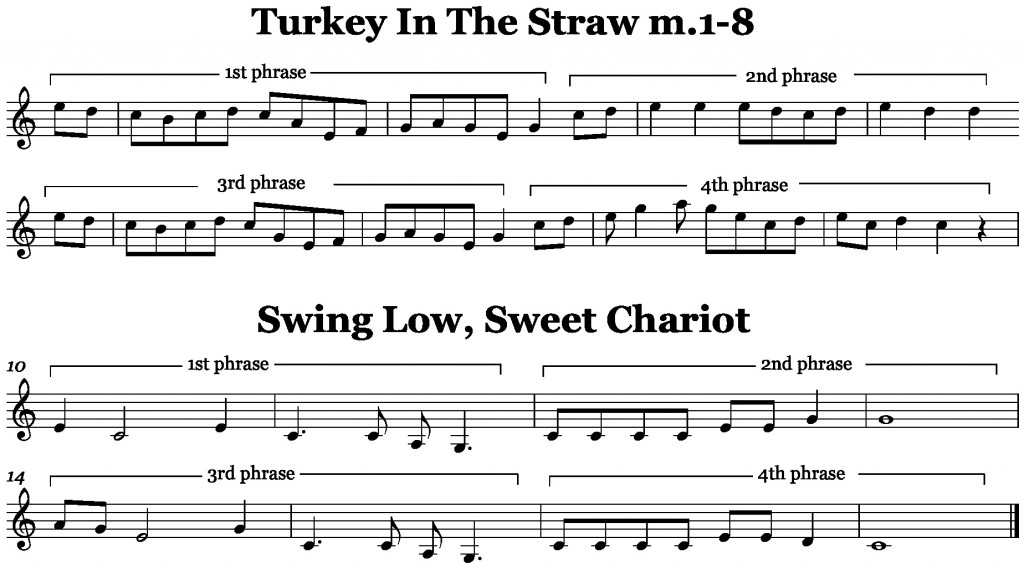

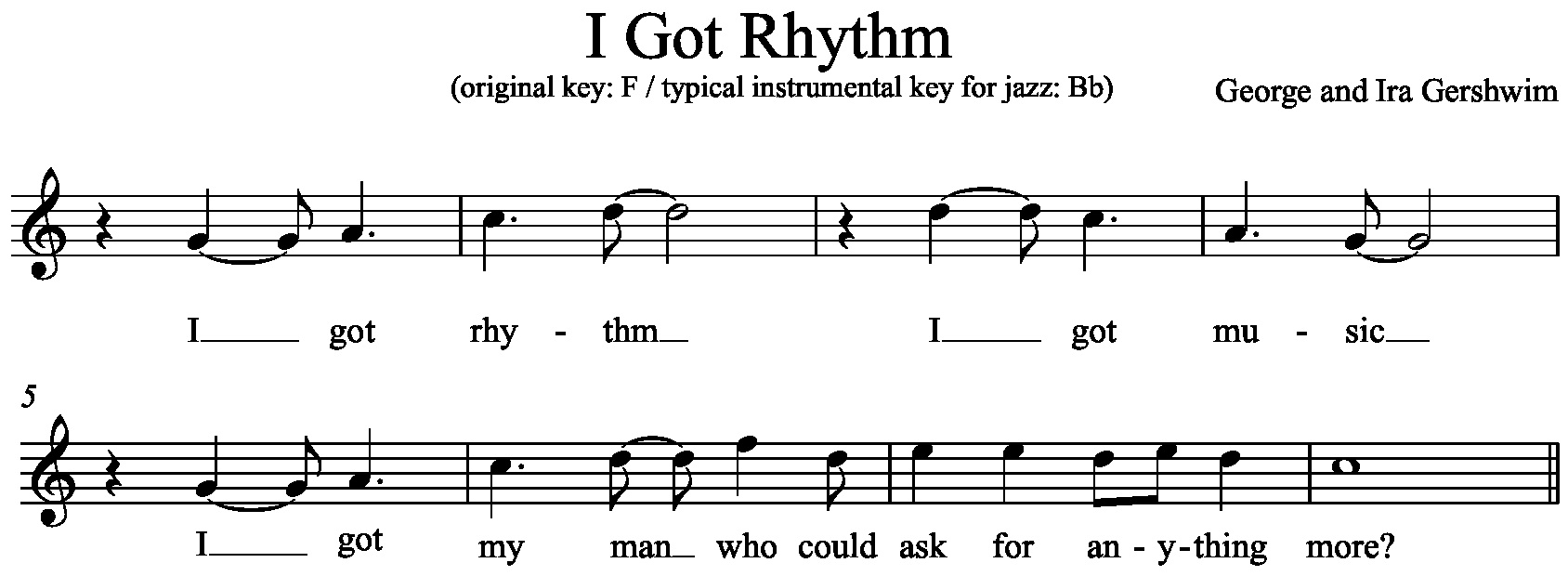

One musical form that Young, Fitzgerald and Stitt all used to display their chops at trading fours was ‘Rhythm Changes’, the jazz term for compositions based on the harmonic progression and form of George and Ira Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’. ‘I Got Rhythm’ is based on a phrase structure that can be seen in earlier folk and spiritual tunes such as ‘Turkey In The Straw’ and ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’. These tunes have a structure of three successive two-measure phrases, all ending on a note other than the tonic (usually the fifth of the scale), followed by a final consequent phrase that begins and ends on the tonic.

The innovation of ‘I Got Rhythm’ lies in the way that it starts with the type of two measure phrase used in these songs, but follows two of these short phrases with a continuous four-measure phrase in m. 5-8.

The relationship of ‘Turkey In The Straw’ to ‘I Got Rhythm’ can be seen, among other places, in Bud Powell’s solo on the rhythm changes tune ‘Squatty‘, where he quotes eight bars of ‘Turkey’ at the end of the second solo chorus (after opening the chorus with a quote from ‘Salt Peanuts’.)

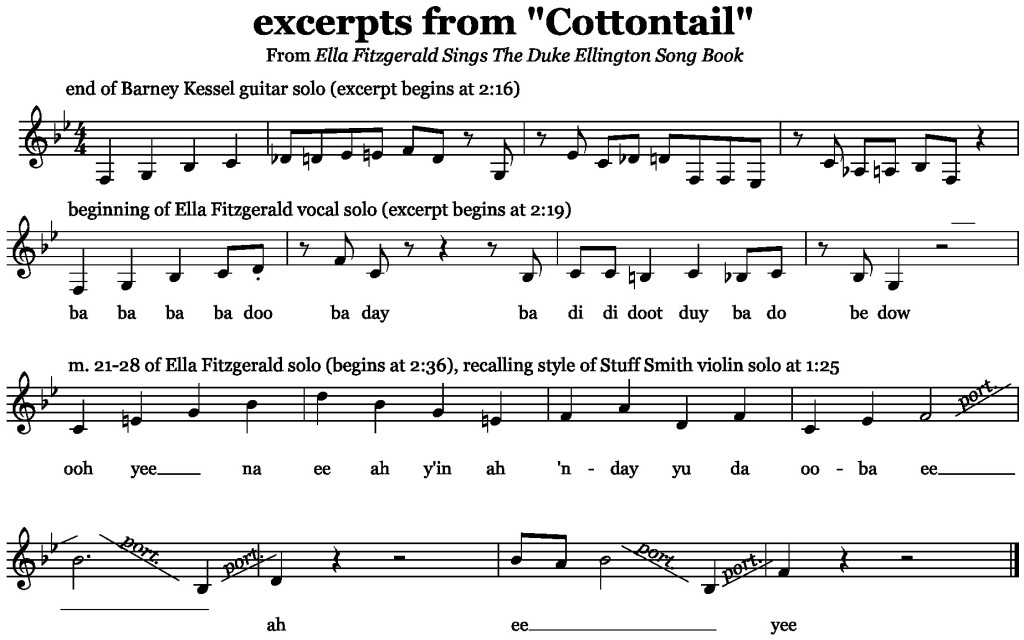

The melody of ‘Lester Leaps In’, one of the first of many jazz tunes based on ‘I Got Rhythm’, updates this phrase structure by only using phrases that are clearly 4 measures in length. However, when Young and his bebop successors begin to improvise on the ‘Rhythm Changes’ progression, their familiarity with the original melody of ‘I Got Rhythm’ (which was in the jazz repertoire along with the tunes based on it and appears on recordings by both Parker and Fitzgerald) comes through the in the way that they generally begin their solos with a two measure phrase in m. 1-2 of the form and then build toward a four measure phrase in m. 5-8. Examples of this kind of solo include Lester Young’s solo on ‘Lester Leaps In’, Charlie Parker’s solo on ‘Shaw Nuff’ (both included in Scott Reeves’ textbook), and Ella Fitzgerald’s ‘Cottontail’ solo. Ella’s full chorus solo on ‘Cottontail’ is a remarkable example of an improviser responding to multiple sources of inspiration from her immediate surroundings. She begins by using a phrase from the end of Barney Kessel’s solo , and a few bars later, thoughtfully reflects on the large-scale structure of the performance by using an idea from violinist Stuff Smith’s solo during her navigation of the bridge. (In the examples below I am drawing from Rebecca Wood’s transcription of the solo, which I have also edited. My own attempt to transcribe Ella’s scat syllables is below the staff.)

The focus on creating four measure phrases intensifies in the trading-fours sections that follow the individual solos on the recordings of ‘Cottontail’ and ‘Lester Leaps In’ Young trades with Count Basie on piano in ‘Lester’, and Fitzgerald trades with Ben Webster on ‘Cottontail’. Both of these trades take after the tradition of the ‘tenor battle’, classic examples of which can be heard in the Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis recording of ‘Lester Leaps In’ and the recording of Sonny Stitt’s Rhythm Changes tune The Eternal Triangle from the album ‘Sonny Side Up’. What holds my interest in listening to these classic battles is the question of how each soloist will continue to equal or surpass the repeated challenges of the other. (There’s no question of whether the challenge will be met, because the players involved are among the giants of the music.) In addition to being stunning displays of musical virtuosity, these trading sections are also in some sense endurance contests for the players: the trading goes on for a number of choruses comparable to (or exceeding) the length of the individual solos. However, in the Lester Young/Count Basie and Ella Fitzgerald/Ben Webster trading sections, the situation of two contrasting instruments rather than two identical ones, and the limitation of the trading to one chorus, creates a situation that is less overtly competitive and thus more conversational, but no less energetic.

In future posts I hope to share transcriptions of the trading sections in ‘Cottontail’, ‘Lester Leaps In’ and ‘The Eternal Triangle’. I wish I could require John McCain and David Gregory to listen to ‘The Eternal Triangle’ in particular, where Sonny Stitt and Sonny Rollins manage to sustain an extended and energetic ‘battle’ – with good reason, it’s one of the most famous recorded tenor contests in jazz history – but they never stop listening to each other and moving the conversation forward. For now, I hope these thoughts might give you some ideas for composing (or improvising) your own rhythm changes solo. Also, if you can think of any examples of great trading sections – trading fours but also two, eights, etc. – in recordings that you know of, jazz or otherwise, I encourage you to leave a comment mentioning them, and perhaps also including a hyperlink. As jazz players sometimes say to each other in mid-song: ‘let’s trade!’

Hey there, Peter here. One of my earliest impressions of music theory was the idea of ‘call and response’, of which trading twos and fours is an example in an improvised context- but all of music can be separated into call and response, for better or for worse. Sometimes it helps, but i’ve heard a bunch of hippies do something that would probably better be categorized as fuddled howl. Modal jams. Anyway, if I don’t know what to compose next, I just pose what I just wrote to myself as a question and try to think of silly ways to answer that question.

Also, this my jam. Snarky Puppy. Ray Vega is all about them, being the guy who introduced me to their sound. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JG84aBQeGHA

here’s the studio version, cleaner but the other one is more spontaneous. i couldn’t leave this one out because it’s pure money

http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&v=67PMG2nVs4k&feature=endscreen

This doesn’t exactly pertain to trading, but it’s an example of awareness of fellow musicians.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5X_3CkOwUPk

This Jim Hall Trio recording of Angel Eyes from his 1975 “Jim Hall Live!” recording. He opens his solo with an extremely distinct motif (in scale degrees it is 3 1 1 7 1, all 8th notes beginning on the first beat of the measure). He then manipulates this motif throughout his (very long) solo. The bass player, Don Thompson, also begins his solo with the same lick and uses it to launch into his own exploration of the changes. In my ears, this helped tie the performance together as a single entity.

Basically, this was what we’ve been working on a little bit during class (similar to “stealing” musical ideas for outlines)? I do admit, it would be a challenge to go with “trading” when you’re working with other musicians who may come up with something very similar. I would like to try that more.

This video around 10 minutes or 12 possibly, Pass and Peterson trade solo’s. Pass at one point goes a chromatic type thing up and ends with a more diatonic riff then Peterson does the same pattern of Pass’s chromatic’ but going down. http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=endscreen&NR=1&v=F63kZNKcBcY&list=PL2B2782650E4E39AD

one more video with a different Peterson quartet with Terry at one point kind of trading with himself between flugel and trumpet http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WkbR9XQZNJw&list=PL2B2782650E4E39AD

at 3:05. Which I thought was interesting. Because fours are sometimes described as question and answer. Would be an interesting way to practice soloing to make sure your solo is melodic and has that conversation thing going.

Here’s one more example of trading I just found. It’s not jazz but it’s great playing nonetheless. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AzYmGDZrKe4

(Trading section begins at about 5 minutes in.)

The trading between the tenor players at 3:20 in ‘Slow Demon’ is a great example of trading, also of how bebop language works well in this context.

The first chorus of the solo is definitely a great example of developing a simple idea. In the first chorus he also uses pieces of what in class we call the ‘turnaround lick’ – first the ‘tail’, then the beginning. His version of the tune changes the feel from the original triplet/swing feel to straight eighth; he also stretches out the form to twice as many measures as usual – if I were transcribing it I’d write it in cut time and use eighth rather than sixteenth notes…

There’s a lick Peterson uses for the first time at 3:58 – and uses several times afterwards – that is very similar to the one that appears in m. 20-21 of the second chorus from Clifford Brown’s ‘Pent Up House’ solo. Not sure what you mean by Pass’ chromatic lick – can you find a timing?

Great example, Brad! I think Clark’s trumpet/flugel trading, rather than just displaying his amazing ability to switch embouchures, is an example of how great players sometimes approach a solo as trading fours with themselves, or between themselves and an imaginary second voice. This also suggests that trading fours might have evolved not just as a way add an additional element to a spontaneous group arrangement, but as a way for musicians to practice improvising short phrases and expand their vocabulary by picking up ideas from each other.

It’s interesting to contrast this Derek Trucks tune with the Snarky Puppy tune Peter mentioned – where the Snarky Puppy sax players’ trading uses a fair amount of bebop language, Trucks and Kofi Burbridge on flute create variety through what is sometimes called ‘side-slipping’, i.e. using scales borrowed from outside the key of the moment.

Here is a cool recording of The Bad Plus playing with Bill Frisell: http://www.npr.org/event/music/158004697/the-bad-plus-with-bill-frisell-live-in-concert-newport-jazz-2012

At about 18:30 they play the tune No Moe, a Sonny Rollins rhythm changes. After Frisell, Iverson, and Anderson take their solos there is a chorus of some interesting trading. In addition to the trading, this whole concert is a great example of musicians interacting with each other in the moment.

This whole concert is a great example of musicians interacting with each other in the moment. That’s impressive. Thanks for sharing this article.