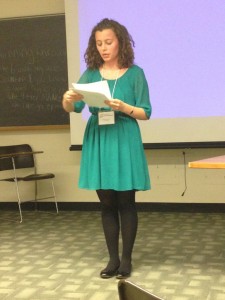

In March, I had the privilege to give a paper at the Syracuse University Undergraduate Conference on Religion and Culture. I have to say that it was one of the most tiring and stressful, but awesome experiences that I’ve had so far as a religion major. I met a lot of brilliant scholars, like S. Brent Plate (the Author of A History of Religion in 5 ½ Objects), and I also met a lot of more senior undergraduates. But before I tell you what this experience was like for me, this intro wouldn’t suffice without giving a shout-out to Lily Fedorko and Ellen Eberst for driving the 5 hours there and back with me, and all of the moral support!!

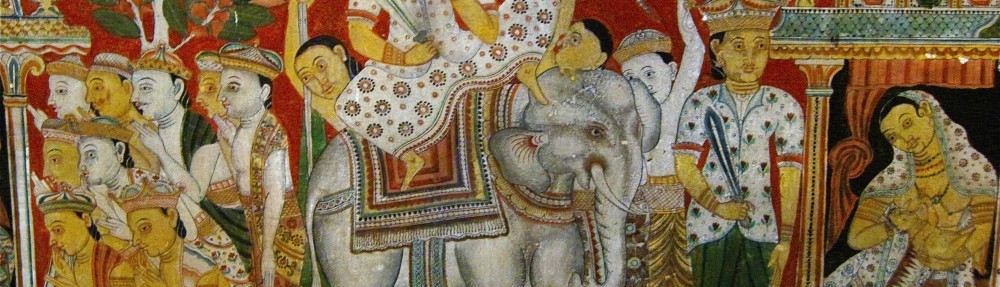

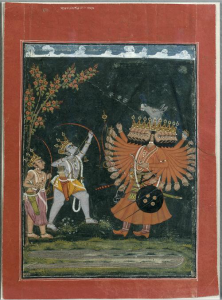

I am interested in religion and gender, and the conference paper that I presented dealt with these topics; but this blog post needs a trigger warning, because in my paper, I explored cultural concepts about gender as well as the contemporary legal issues that surround the sensitive but important issue of rape. In my paper, “Gender in the Age of Contemporary India: Aspects of Masculinity, Femininity, and Contemporary Legal Issues in a Predominantly Hindu Society,” I wanted to sketch out some of the realities of rape in India as well as the ways in which it is impacted by Hindu traditions. This paper specifically discusses motives behind rapes that occur in India, and drew upon various sources including: article publications, legal texts, news articles and the Ramayana, a Hindu religious text. The Ramayana was significant in my research because there is a present theme of gender and women’s bodies, and how these are affected by power and honor. Being that the Ramayana is a historical and culturally influential text, I used it as a touchstone to talk about how Hindus might mobilize religious ideas about rape. To some extent, I found that rape in India is a gendered desire for honor and power (specifically in terms of males), in many of the cases that are reported by females. This may be simple, but I argued that texts are interpreted, and used in many ways, and one of the ways in which the Ramayana seems to be used is to structure patriarchal systems, including rape culture.

This project started out as an blog assignment for my Studies in Hindu Tradition Religion class with Professor Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst. She also helped me to edit my paper very short-notice and very extensively, for which I am eternally grateful. I was so happy to have my paper accepted to the conference, but to give a paper on my own research, that I was completely interested in, was both absolutely nerve-wracking and fulfilling. For me, there was a way in which I had this knowledge that I was presenting that I was seeing uniquely, and that was exciting; but I also had a looming sense that someone might be an expert and ask a question that I should know the answer to—but didn’t. I was scared of drawing blanks, or stuttering over my paper. Plus, I was nervous about the fact that I was presenting on a touchy issue.

So with that said, I think fear deserves a lot of the credit in my success, at least during that point in time, because I was imagining things so hugely out of proportion to the point that when I got there, things seemed much smaller. I was still intimidated, but when I saw that I was in a classroom like those in Lafayette, rather than in a room like Billings Lecture Hall (which is colossal) I felt a lot better. There is a way in which I over-prepared, and that proved to be helpful in my situation.

So with that said, I think fear deserves a lot of the credit in my success, at least during that point in time, because I was imagining things so hugely out of proportion to the point that when I got there, things seemed much smaller. I was still intimidated, but when I saw that I was in a classroom like those in Lafayette, rather than in a room like Billings Lecture Hall (which is colossal) I felt a lot better. There is a way in which I over-prepared, and that proved to be helpful in my situation.

The most important thing that I learned from this conference is that there is nothing to be worried about when you’re the center of attention in a room full of people, at a low-key conference because you have the same thing in common with (almost) everyone else there: you’re there to speak and they’re there to listen to you speak. I think that giving a paper is a great experience if you are interested in becoming an academic because it provides a way to get your name out there, conduct research for a purpose, and practice a key element of academic work.

If there was one thing that I was not expecting from this conference, it was that people (like, real-life PhD candidates and Professors) were impressed by my work (or so I was told!). I was shocked, and still am. But I am also humbled. I think that as undergrads, we might feel that our work is not important because we only do it for a grade in a specific class. In fact, our work is always given a letter, which in a lot of cases, is the only thing that we care about as students. But the conference that I went to showcased everyone’s work as something more than a grade. At the conference, each panel had moderators, who guided us in the sense that they told us how we could, and should do better work; that is, if we were willing to put in the effort. For example, one of the more significant critiques that I received was that my paper was solid, but could be part of some kind of bigger research and therefore, was a work-in-progress. And this makes sense to me because (at least in my universe) everything can, and should be better.

Now that I have participated in a conference, I know that I will probably continue to do so if I have the opportunity again. I have learned that conferences are actually awesome because you have the opportunity to network with great scholars and to hear what they have to say about your own work. To me, this is important because they’ve been where I am right now. Talking to PhD candidates and post-doctoral fellows, about their work and what they had to endure to get to where they are now, was kind of like looking at the light at the end of the tunnel, in terms of all of the hard work that is put into becoming an academic.

In terms of viewing myself as a future academic I have thought about the ways in which I could re-work this research. Ideally, I would like to narrow my research down to a more specific time frame. Right now, the partition of India is the historical context that I have in mind. In this context I would like to look comparatively the motives and dynamics behind the gender violence that occurred among Hindus and Muslims after the establishment of Pakistan as a state for Muslims, and India as a state for Hindus. I hope to find an answer to at least part of this question, as I continue to do work on this project in the future.