Earlier this summer I had the opportunity to visit “The Jeweled Isle,” a major exhibition of Sri Lankan art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Exhibitions of Sri Lankan art in the U.S. are few and far between; to my knowledge, this is only the third exhibition devoted exclusively to the art of Sri Lanka. The first, in 1992-93 at the Sackler Gallery in Washington, DC, focused exclusively on Hindu and Buddhist sculpture, while the second, the 2003 “Guardian of the Flame” exhibition at the Phoenix Art Museum, was limited to Buddhist artifacts. The LACMA exhibition, which opened last December and closed in early July (2019), presents a much broader focus, highlighting the interactions of the diverse communities, ethnicities, and religious identities that have taken root on the island over the past three millennia. This globalized perspective is effectively evoked by the first image that appears at the entrance to the exhibit: the island’s silhouette superimposed at the center of a web-like pattern that simultaneously evokes a network of global connections, and the facets of a jewel, one of the island’s natural resources that has captured the attention of traders and colonizers.

(All photographs are mine, unless otherwise indicated; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, June 2019)

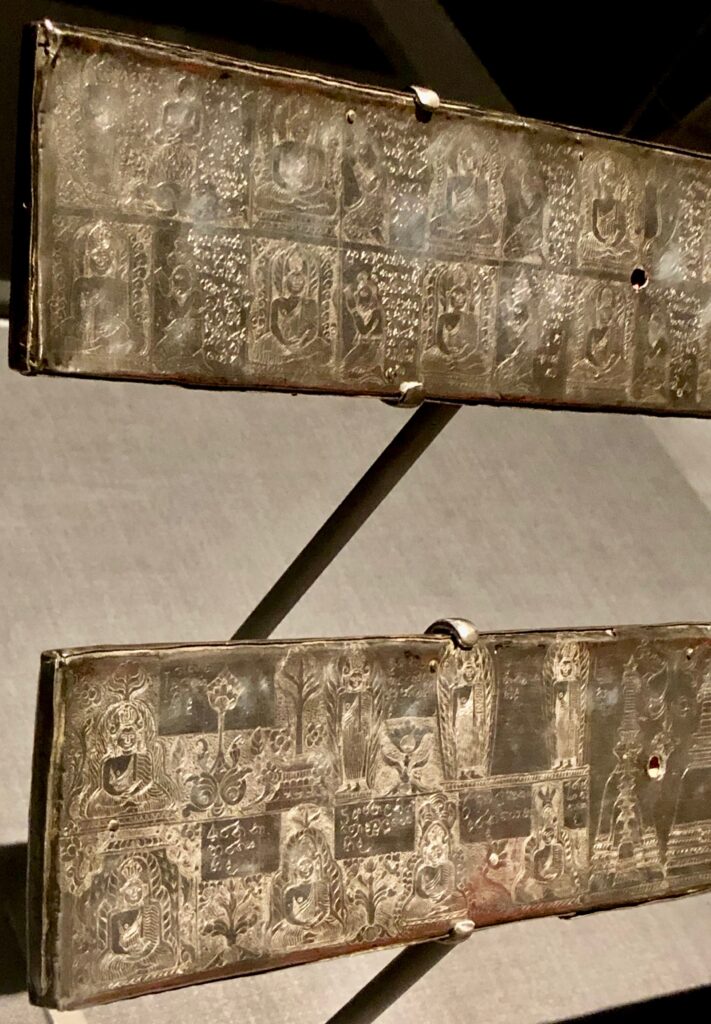

The power of “jewels” is one of the key organizing themes that run throughout the exhibit, linking the human attraction to precious gemstones with two foundational forms of Buddhist practice: taking refuge in the “triple gem” of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and activities centered on the Buddha’s bodily relics, which have long been symbolically and physically linked with precious stones. Buddha relics are typically enclosed in two different kinds of containers, both of which appear throughout the exhibit: in the massive relic monuments (stupas) that spatially and ritually define important Sri Lankan Buddhist devotional sites (displayed here on palm-leaf manuscript covers and as captured by 19th-century colonial photographers), and in stupa-shaped reliquaries, which are either permanently enshrined in stupas or serve as moveable relic containers for devotional purposes. Several examples of reliquaries, labeled “votive stupas,” appear throughout the exhibit, dating from the 2nd-3rd century to the 19th century.

These containers for precious materials evoke another key theme threading throughout the exhibition: the island itself as a physical container, bounded by water, and defined by the comings and goings of different groups of people throughout its long history. As the gallery card provided for the gemstone exhibit notes, in the early centuries of the Common Era the island was known as “Ratnadvipa” (Island of Gems), and legends developed that the gems found there originated from the tears of the Buddha, or of Adam and Eve. Medieval Christian and Islamic texts preserve a tradition that it was the site of Paradise. The island, with its strategic location for global trade and valuable natural resources and commodities (e.g., spices, gems, rubber, coffee, tea), has exerted a powerful centripetal force, attracting diverse groups of outsiders defined by a multiplicity of identity markers (including racial, ethnic, linguistic, and religious differences). Sinhalas, the largest ethnic group in Sri Lanka, trace their origins to North India, and the traditional account of their migration to the island is closely linked to the life of the Buddha: Vijaya, their legendary progenitor, is said to have set foot on the island on the day of Gotama Buddha’s parinibbāna (final passing away). Tamils, who are predominantly Hindu, constitute the second largest ethnic group, and they trace their origins to groups of settlers from South India. Other ethnic groups include the Väddas, an indigenous group whose ancestors are regarded as predating the arrival of the Sinhalas; Moors, descended from Arab-speaking traders, who are predominantly Muslim; and Malays, also predominantly Muslim, whose ancestors came from the Malay Archipelago. Sri Lanka was also populated by three successive groups of European colonizers, beginning with the Portuguese in the early 16th century, followed be the Dutch in the 17th century, and finally the British who gained complete control of the island, then called Ceylon, in 1815 and ruled it as a British crown colony until its independence in 1948. The Burghers, a Eurasian community defined by links to a paternal ancestor of European descent, constitute an additional group.

All of these communities, with the exception of the Malays, are represented through the objects on display, most of which belong to the LACMA collection, supplemented by objects borrowed from a number of other museums, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and New York’s Metropolitan Museum. Without attempting to provide a detailed account of the impact of European colonial rule, or of the long history of inter-ethnic conflicts on island, the objects on display effectively evoke the complex interactions of diverse groups, pointing to moments of shared interest and appreciation, as well as contestation and social othering. This is accomplished through the curators’ choice of objects for display, the exhibition’s integrated spatial layout and unified aesthetic plan (designed by a prominent Los Angeles architecture firm), and the strategically placed signage, which provides essential historical and cultural information. I was particularly impressed by the use of 19th-century photographs strategically placed throughout the exhibit to highlight the impact of British colonial points of view, including their fascination with Buddhist archaeological sites, aspects of the natural environment, and “native” Sri Lankans represented by shots of humble villagers, as well as members of the Kandyan aristocracy, a group that lost power with the British conquest of Kandy in 1815. These photographic displays culminate near the end of the exhibition with a series of 20 photographs by Reg van Cuylenburg (1926-1988), a Sri Lankan photographer of Kandyan Sinhalese, English, and Dutch descent who toured the island from 1949-58, documenting people and places in the newly independent nation. It is revealing, I think, to compare the very formal and static character of the 19th-century photos with the vibrant and dynamic force of van Cuylenburg’s “Village Girls Bathing” (see below). A final sign at the end of the exhibit, titled “Buddhist Legacies and Island Memories,” makes a poignant contrast between the optimism that informed van Cuylenburg’s work, and the more recent history of ethnic conflict, concluding: “Among the greatest tragedies in Sri Lanka’s recent history is the civil war (1983-2009) that pitted Sinhalese Buddhists against Tamil Hindus, two groups that had coexisted and comingled for much of Sri Lanka’s history. It is unlikely that such a prolonged conflict could have been foreseen when Sri Lanka won its independence from Britain in 1948. Young Sri Lankans of that time, including the photographer Reg van Cuylenburg, reveled in optimism for the future of their island nation, which had been strewn for two millennia with the jewels of diverse communities, cultures, ethnicities, and religions.”

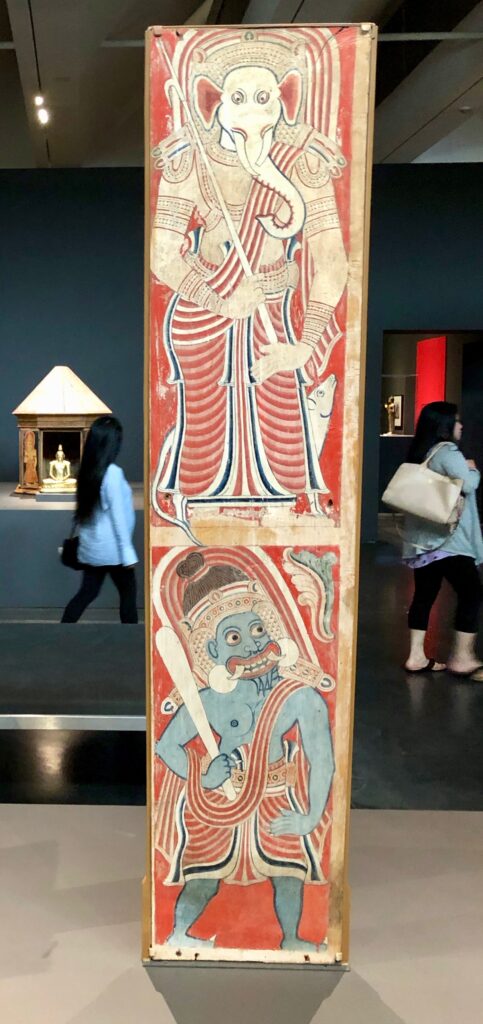

Much could be said about the ways that the exhibit portrays the deep integration of “Buddhist” and “Hindu” religious practices in the lives of Sri Lankans, providing a visual counter-narrative to one of the enduring legacies of British rule in South Asia—a taxonomy of knowledge that represented “world religions” such as Buddhism and Hinduism as tightly organized and exclusive systems of belief that closely aligned with other exclusivist racial/ethnic and linguistic categories (e.g., Buddhist/Sinhala and Hindu/Tamil). This integrative approach is apparent in the prominent display of a series of 17th-18th-century painted wood panels from the LACMA collection, which most likely served as window or door panels in a Sri Lankan Buddhist temple (their original provenance is unknown; they came to the museum as a donation from the actor James Coburn). These depict major gods associated with Indian Brahmanical religion and planetary deities, as well as devotees and powerful local spirits. As the gallery card notes: “Sri Lankan Buddhist practices often involve honoring various deities who were originally assimilated from popular, folk, and Indian traditions in order to undergird Buddhism’s relevance to the everyday lives and goals of worshippers … [who] seek protection and benefits in their present lives, and the gods found throughout Buddhist temple complexes in Sri Lanka aid their efforts.” The two panels depicted below show the popular elephant-headed god Ganesha, and probably Shakra (Indra), who figures prominently in Theravada accounts of the Buddha’s life; a demonic spirit (commonly depicted as fierce guardians in Buddhist temples) and a female devotee are depicted in the lower registers of each panel.

The final object in the exhibition might at first strike the viewer as incongruous, as it was created by Lewis deSoto, a contemporary artist of Cahuilla Native American ancestry. Titled “Paranirvana (Self Portrait),” it is a 26-foot inflatable image of the reclining Buddha with the artist’s own face. Like the inflatable lawn ornaments that appear during the holidays in the front yards of many American homes, it relies upon an electric fan to keep it inflated. As the nearby label notes, the sculpture’s inflation in the morning and its deflation at the close of the day calls to mind the rising and falling of “spiritual breath” (prana) in yogic practice, as well as the cycle of birth and death (samsara). It’s connection to Sri Lanka? It is inspired by the massive 12th-century reclining Buddha image at Gal Vihara, part of the Polonnaruwa temple complex in Sri Lanka. It seems particularly fitting that the last object in the exhibit simultaneously looks backward toward an ancient Sri Lankan Buddhist monument, and forward toward new globalized forms of Asian religious practice (yoga, as well as Buddhism in its multiple North American hybridized forms). And, once again, the curators have juxtaposed a final example of a British colonial gaze in the form of a 19th-century photograph of the Gal Vihara sculpture.

I feel very fortunate to have been able to undertake this academic pilgrimage to Los Angeles to view this remarkable exhibition, which has given me much to reflect upon. I also want to express my gratitude to Dr. Tushara Bindu Gude, co-curator, who very graciously walked me through the exhibition and gave me a better understanding of its genesis.

Evan Thompson’s

Evan Thompson’s