I was going to post something to mark the 25th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear accident, but Sarah Phillips has already posted something so good, saying many of the things I would have wanted to say, that I will simply link to her article at Somatosphere and add some personal notes of my own. The result reads more like a love letter to post-Chernobyl Ukraine than a lament. So be it.

First, a couple of choice bits from Sarah’s article:

Bizarrely, an increasing number of Chernobyl tourists are avid gamers and enthusiasts of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. video games (e.g. Shadow of Chernobyl and Call of Pripyat), in which players battle zombies, mutant animals, and other improbable foes in a hyper-sensationalized contaminated “zone of alienation.” (Imagine Chernobyl’s absolute worst possible effects, multiply by ten, add steroids, bring on the Kalashnikovs, and you have S.T.A.L.K.E.R.) One suspects that after battling through a surreal virtual “zone of alienation” these gamer-tourists probably experience the “real” Chernobyl zone as something of a letdown.

I refer to this use of Chernobyl imagery in the section of Ecologies of the Moving Image where I discuss Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, which is also coming out in the next issue of the open-access cinema studies journal Film-Philosophy. (I’ll link to it when it’s out, and will post an excerpt from that section here sometime soon.)

Continuing from Sarah’s article:

On the other hand, there is much that is unexpected about the supposedly “uninhabited” 30- kilometer zone around Chernobyl. Depending on the season several hundred people live in previously abandoned houses in the zone. Called samoseli—“self-settlers,” these people receive food, medical care, and social services from the Ukrainian state, but also grow their own food in the often highly-contaminated soil.

My friend Myron has been interviewing some of these samoseli for a dissertation he’s working on at the California Institute of Integral Studies, and for a film marking the 25th anniversary. I sent the filmmakers about a half-hour of video footage I took in the Chernobyl area in 1989, when I traveled there to interview folk artist Maria Prymachenko (a.k.a. Pryjmachenko, Primachenko, Pryymachenko).

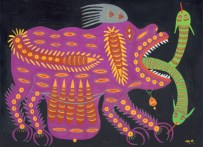

That footage can be viewed here, but be forewarned that it’s a lengthy segment and may take longer to download than to actually watch. There are no subtitles and the conversation is all in Ukrainian, but Prymachenko’s Polissian Ukrainian is so delicious to listen to, it may not matter whether you understand a word of it or not. The art work, however, is amazing. (Check out the cow that ate grass by the fourth reactor block, about seven minutes into it.) Nowadays Prymachenko would be called an “outsider artist,” or a “naive” or “primitivist,” but she was honored in her home country, not an outsider at all, and was eventually honored by UNESCO as well.

(Accompanying me in the video is the wonderful flaming-red-haired Rita Dovhan’, who took me in and housed me for a couple of months when I realized that the dorms at the University of Kyiv were a lousy place to stay, along with her husband, sculptor Borys Dovhan’, and my dear friend Olena Leonenko, now a singer in Poland. I also traveled to the area again in spring 1990 with David McTaggart of Greenpeace International. My cloak-dagger-and-vodka tale of that experience is captured in #18 of these random bits.)

Sarah Phillips speaks of those for whom Chernobyl is a “defining event of their lives.” It was and is that for me.

I first heard of the event from a friend and roommate of mine at the time, a Polish-Ukrainian post-Solidarity refugee (i.e., a Pole of Ukrainian descent who left Poland with his parents in the early 1980s). We had been involved in a theater group in Toronto called the Avant-Garde Ukrainian Theater, begun by him and a few friends and inspired in part by Polish theatrical experimenters like Jerzy Grotowski, Tadeusz Kantor, and the international post-Dada avant-garde. When he told me what he’d heard had happened, he spoke of “tragedy” and “cover-up,” and in the age of Gorbachev, I knew this would be a major game changer.

It was. Ukrainian environmental groups sprouted up over the next few years, especially among writers in the official Writers’ Union, which began to spearhead a critical reconsideration of Soviet history that had not been allowed for decades in Ukraine. The Writers’ Union journal Literaturna Ukrayina was the only place at the time where a westerner could actually read any of this critical writing. As a geography teacher in a Ukrainian heritage language program school in Toronto, and a co-founder of the anarchist Toronto Free University (which flourished for a few years in the mid-1980s, not to be mistaken for the Free University that emerged several years later), I made it a point to find out all I could about these groups and to eventually get in contact with them. With the environmental solidarity group Ecolos, which I co-founded in Toronto, I was able to do that.

I spent 1989-90 as a Canada-USSR scholar in Ukraine researching the cultural impacts of the Chernobyl accident. It was the most interesting year of my life. Traveling around Ukraine and other parts of the Soviet Union was relatively easy (though I didn’t have permission to travel outside Kyiv and Lviv, but I only ran into trouble a couple of times from overzealous officials). I managed to spend a lot of time with artists, writers, musicians, and political activists of one kind or another, active in the Green movement, the Ukrainian independence movement, and the burgeoning independent music and arts scenes. I recorded over 18 hours of video footage, and upon my return began to edit it down into a personal essay-style documentary, for which I had written a script and begun crafting a storyboard. But by that time I had to quickly finish up my Master’s thesis and right after that I got started on my Ph.D., and the video was never completed.

I’ve written a bit more about Chernobyl here, and gone back to Ukraine and Eastern Europe nearly a dozen times since then. It’s become one of my academic research areas, as well as a lost and recovered homeland for me. (I was born to a family of post-war refugees from western Ukraine.) I’ve written about cultural identity in post-Soviet Ukraine, about art in the border zones of Slovakia-Ukraine-Poland, about the use of folklore, archaeology, and imagined prehistory for carving out global and anti-global post-Soviet Ukrainian identities, about religion (notably the revival of paganism), and about the Ukrainian environmental movement. A selection of these are available online; I’ll add a few others at some point.

I’ve gone back to lecture at the University of Kyiv on a couple of occasions, and have (sadly) started many more projects than I’ve completed (for instance, on culturally contested landscapes across the country; on urban space in post-Soviet Kyiv; and on a critical reconsideration of the meaning of Chernobyl).

Despite the Stalinist architecture that mars the entire center of the city, the Khrushchevite architecture that mars the surrounding parts, and the more out-of-control uglification of the city since it entered no-holds-barred capitalism, Kyiv (Kiev in Russian) remains one of my most beloved cities in the world. With its location cradling the Dnipro River and its islands and its more-than-millennium old history, it could easily top Prague or Budapest for beauty, had it been taken care of properly over the years. Ecological and urban activists have long called for better planning, but the city’s politics have remained mired in a post-Soviet miasma it has never managed to shake off.

Lviv is entirely different, a piece of Hapsburg Central Europe that’s managed to eke out some of its former beauty thanks to its UNESCO World Heritage status.

I have many friends I miss in Ukraine, including those with whom I have shared moments of great sadness and joy over the legacy of Chernobyl. For me the event of April 26, 1986, has always been a personal life-changer, bringing my ancestral heritage into convergence with my environmental, political, and cultural interests in a way that defined a lot of what I did for years following the accident. (I entered the graduate program in Environmental Studies at York University the year after the Chernobyl accident. I’ve remained in that interdisciplinary field since then.)

Here’s a link to a song my band Stalagmite Under a Naked Sky (a.k.a. Vapniak Pid Holym Nebom, a.k.a. Vapniaky) recorded about Chernobyl in 1990, called Ukraine My Atomic Land. I’m on synthesizer there, modeled a bit after Pere Ubu’s Allen Ravenstine, though the synth is buried too deep in the mix here. (We have other recordings, very different ones with different instrumentations and feels, but they’re all buried somewhere in the pre-digital archives.) The song was written by members of the Polish-Ukrainian rock band Oseledets’. The lyrics go roughly as follows (repeating these phrases over and over):

Ukraine, Ukraine, my strange atomic land (repeat). Flee, flee, flee, flee, Ukraine, my strange atomic land.

Human, again, again, again. Nuclear blood flowing in your veins, Nuclear bloody brain of yours, Nuclear end of yours. Again, again, again.

We took it pretty seriously at the time. (And I think our singer, Tanya Chorna, got as close as anyone in Toronto got to Nina Hagen in her stylistics here.)

The Japanese may wish to take nuclear energy pretty seriously as well these days.

Hundreds of thousands of years (for radiation to hang out in the biological systems into which it’s released) is a long time.

Hi Adrian,

We too join you to pay attributes to those you had lost their lives in that incident and let’s raise over voice to free the world from NUCLEAR BOMB.

Thanks for giving us an opportunity to participate in the 25th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear accident.

Regards,

Mhedi.