‘Everybody’s Inside Blues’ is a through-composed melody line on the twelve-bar ‘jazz blues’ progression. Here’s a live recording of it (in the key of F) from a gig I played a few years ago with guitarist Steve Blair and bassist Jeremy Hill. As I continued to play the tune, I made an arrangement of it in B flat for Birdcode, the quartet I play in, breaking up the single melodic line I played with Steve and Jeremy into two parts. One part is played by my right hand and sung by Amber deLaurentis, and the other part is played by my left hand and doubled by bassist Justin Dunn.

The tune is written in the style of Charlie Parker blues heads such as ‘Cheryl’, ‘Relaxin’ at Camarillo’ and ‘Chi-Chi’, and illustrates a couple of concepts related to improvising on the blues form. It’s a melody line that ‘makes the changes’ (jazz terminology for outlining the chord progression by highlighting the differences between chords.) In order to understand what this means, it is crucial to study and learn to play an outline such as this basic seventh scale outline of the C blues progression. (The seventh scale outline can be heard at the beginning of the linked recording; it is followed by two more choruses that break the the seventh scale outline down to a pentascale outline and then a triad outline. Learning one of these simpler versions first may be helpful if your technique is more basic.) Pianists should learn the scale outline with their right hand while playing the chord progression in their left, and players of all other instruments should practice playing the outline with the accompaniment that can be heard at 1:24 after the choruses of scale outline.

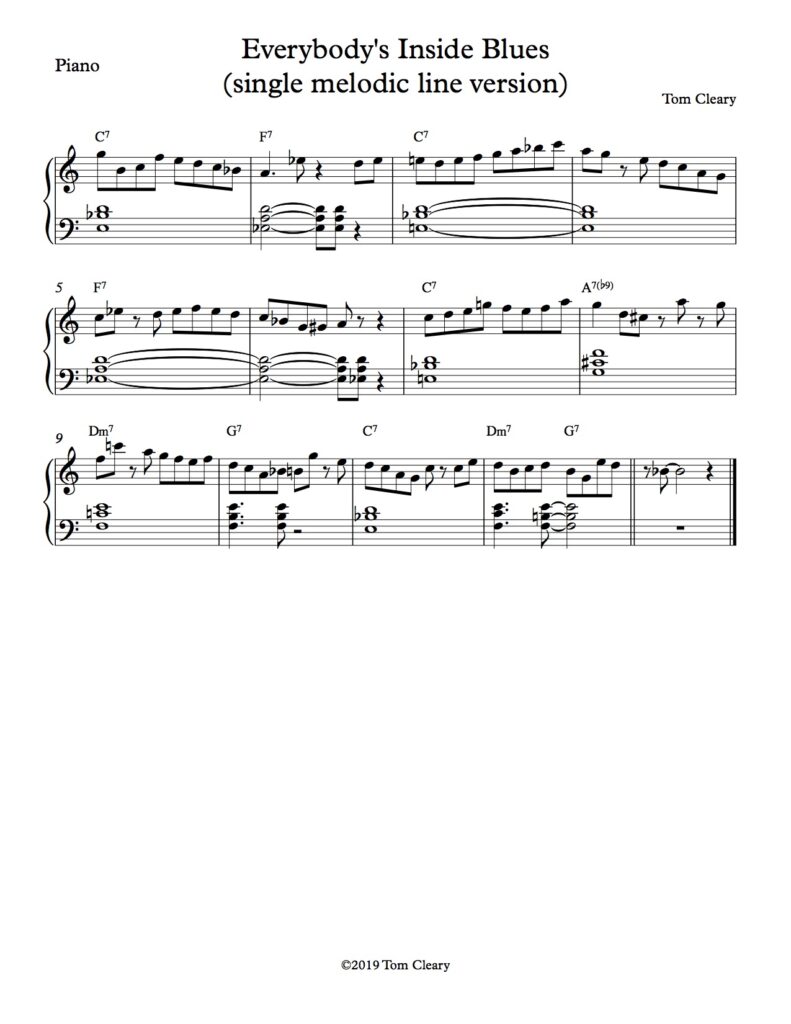

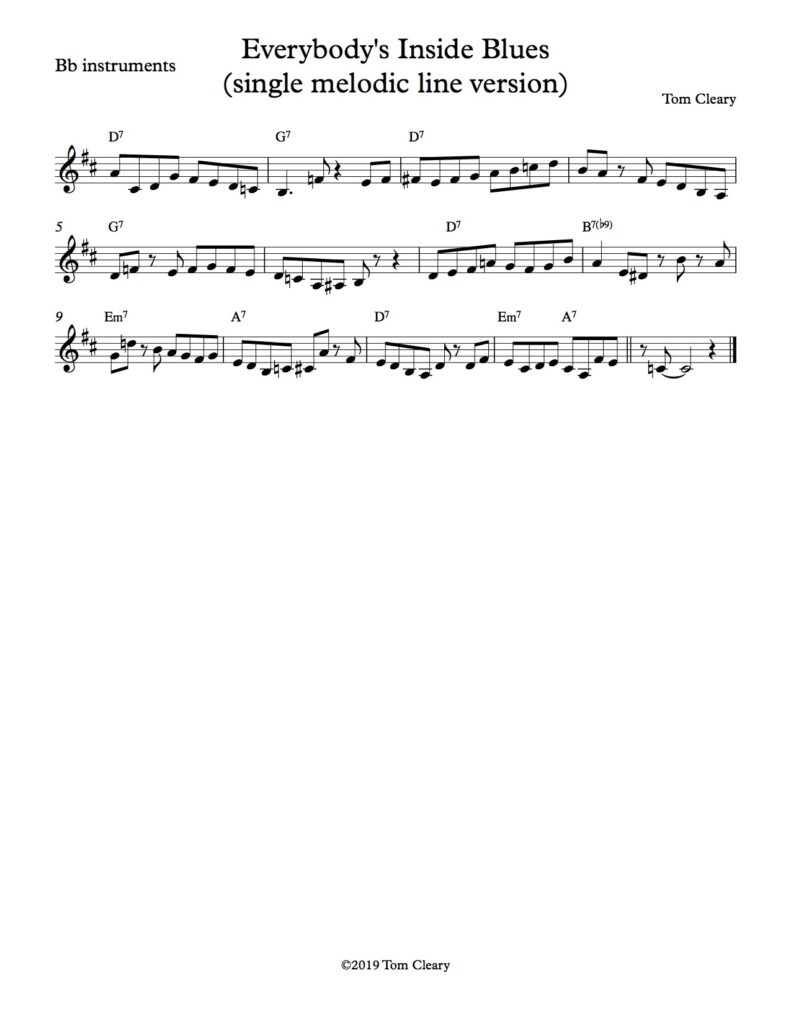

At the bottom of this post are charts for Everybody’s Inside Blues in the key of C, the key of many wonderful performances on the jazz blues progression including Duke Ellington’s C Jam Blues (performed in the linked recording by Ella Fitzgerald and Count Basie) and Sarah Vaughan’s Sassy’s Blues.

Many improvisers, particularly rock and traditional blues players, take an approach to improvising on the blues that is less chord-oriented and uses one or two scales (as in Eric Clapton’s solo on Robert Johnson’s ‘Crossroads’). The one-or-two-scale approach to improvising on the blues is a musical game where working within a limited space challenges the player to come up with multiple strategies for using that space, something like half-court basketball. ‘Making the changes’ is a musical game with more goals, using a more harmonically complex version of the blues progression, that many jazz improvisers engage in either for an entire solo (as in Charlie Parker’s solo on ‘Billie’s Bounce’) or for certain sections of a solo (such as Art Farmer in his solo on Sonny Clark’s ‘Cool Struttin’. This can be heard at 2:11 in the linked recording.) This approach to the blues could be compared to slalom skiing, where the time of an average event is comparable to the time of an average drive to the hoop in half-court basketball, but the skier has to navigate a number of pre-ordained obstacles and cover more ground during that time, while the half-court hoops player battles a moving obstacle in a more limited space.

From the perspective of the contemporary jazz player, being able to play the ‘make the changes’ game is an essential skill which frees one from having to navigate a twelve-bar progression with one or two scales (which might be compared to the situation of having to play a 9-hole golf course with one or two clubs.) ‘Everybody’s Inside Blues’ also involves another game that improvisers play, particularly within the bop tradition: re-using a melodic motive two or more times and placing it in a different rhythmic context, harmonic context or key each time to give it a fresh sound. This game is not, like ‘making the changes’, an essential component of the improviser’s toolbox but is rather a specialty of certain players, like base stealing in baseball. Sonny Rollins’ ‘Oleo’ (discussed in my Viral Rhythm post) and Thelonious Monk’s ‘Straight No Chaser’ are both composed melodies where this kind of rhythmic re-use occurs. Charlie Parker was adept at playing the rhythmic displacement game in improvised solos, such as in the bridge of his solo on ‘What Is This Thing Called Love’ where he uses the same three-beat lick two bars apart, with the second use transposed down a half step and moved from beat 3 to beat 2 of the measure. (This is discussed in my post What Is This Scale Called?)

‘Everybody’s Inside Blues’ has a number of instances where licks are re-used in a different context. After using what Barry Harris calls the ‘5’ lick in the first three beats, I use what he calls the ‘4’ lick in two different transpositions (on the first two beats of meas. 6 and 10). For an explanation of the 5,4,3 and 2 licks, see my post on Charlie Parker’s ‘Anthropology’. It also uses a lick borrowed from Louis Armstrong’s ‘Hotter Than That’ solo in two different rhythmic placements (the ‘and’ of 1 in m. 4, the ‘and’ of 3 in m. 10).

These borrowed phrases are an example of another non-essential but fairly common practice in jazz improvisation: quoting melodic phrases from various sources, such as popular songs, classical pieces or other improvised solos. Great examples of this include Clark Terry’s solo on ‘Straight No Chaser’, which begins with a quote from ‘Frankie and Johnny’, and Dexter Gordon’s solo on ‘Sticky Wicket’, which begins with the same quote and moves on to a number of others, including ‘Things Ain’t What They Used To Be’, ‘Shortnin’ Bread’ and ‘Entrance of The Gladiators.’

Besides using the word ‘inside’ in the jazz sense of working within the harmonic structure, the title also refers to a spring break Amber and I spent one March in Montreal, where temperatures were so frigid that we, along with much of the city’s population, did most of our walking travel in the city’s many underground tunnels.

As always, I encourage comments of any kind on this post. I hope you’ll learn ‘Everybody’s Inside Blues’. I also encourage you to try writing your own through-composed melody line on blues changes that uses a line based in eighth notes to ‘make the changes’.