Welcome to UVM Blogs. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!

Expectation States Theory Steps

Expectations States Theory

Berger, Joseph, Bernard P. Cohen, and Morris Zelditch. 1972.

Cohen, E., 1994 (p.34)

1. Status Characteristics

“They’re Everywhere!”

2. Task Appears

3. Activation of Expectations

Resulting in Status Order Effects

SS=SA+SP

4. Behavior Results

Unequal Talking and Working Together

Unequal Opportunities To Learn

Structures Inequitable Levels of Content Acquisition

5. Status Intervention Treatments

• Groupwork

• Rich Tasks

• Multiple Ability Treatment

• Assigning Competence Treatment

6. Behavioral Results

More Equal Talking and Working Together

More Equitable Opportunities To Learn

Higher Levels Of Content Acquisition For All

A Brief Synopsis of Complex Instruction

A Primer To Expectation States Theory

Senior Seminar

C. Rathbone 3/10/08

In normal, everyday, regular life, we judge the world around us by they way we’ve been taught to judge the world around us. Every one of us has a normative reference group in our head. This is a group whose behavior and actions in all kinds of situations define for us what is normal and acceptable. This normative reference group also has particular characteristics of appearance and behavior. The fact that this imaginary yet powerful group defines the world as “right” to us means we give it and their judgments particular power and authority and influence. Another word for “power, authority, and influence” is “status.” Status is an attribute we perceive in others that determines how we behave in relationship to those “others.” If we imbue a person with high status, then we place an expectation on them that they will perform in a certain way.

The sociologists who thought up Expectations States Theory (EST) have investigated how power and authority and status play out in laboratory experiments. Often these experiments involved naïve participants placed in situations where their behavior was observed as they interacted with research assistants who assumed different postures to “test” the naïve participants’ reactions. One of the many findings of EST is that we behave differently depending upon how we perceive the people around us; and, the people around us behave in certain ways depending upon how they are treated by those around them. EST reveals a two-way street of expectation and response. The famous studies by Rosenthal were part of this genre of sociological inquiry. Rosenthal randomly assigned students of varying achievement levels to various classrooms. He informed the teachers that certain groups of students were high achievers when in fact achievement was a randomly distributed variable within those groupings. When end of the year achievement tests were administered, the low achievement students did remarkably better. This “Pygmalion Effect” has been replicated many times and is a good example of the power of perceived status and expectation.

Elizabeth G. Cohen is almost singularly responsible for moving the study of expectations states from the laboratory to the classroom. Over the course of thirty years, she and her able group of graduate students, almost all of whom had public school teaching experience, gradually, step-by-step carried out a research program that documented how unequal status in classroom small group work creates differential conditions of achievement outcomes based on a student’s status. Lower status students contribute less in cooperative group work because the higher status children in the group think they have nothing to contribute to the group work. Likewise, higher status students contribute more in cooperative group work because they carry a kind of privilege that comes with high status, the privilege of being looked to for leadership in small group activities. As a result, they often run the groups, get lots of opportunity to process the academic tasks, and learn at higher rates all because others think they know more. They may know more, but they may also not know much about a particular area of investigation even though they are looked to by others to “lead on.”

Cohen’s research traces how unequal status plays out in small group work in schools. She created a set of research-based strategies that as a whole are called Complex Instruction (CI). CI includes several status interventions that interrupt business as usual and create conditions of interaction in small groups that cause higher status children to want to include lower status children in the group work conversation. When this occurs, rates of talking and working together for all children in a group increase, engagement in the task increases, and learning improves.

Cohen’s steps are diagrammed below. What follows is a brief summary of Cohen’s interpretation of EST and her interventions that counter its negative effects.

1. Status Characteristics.

We all carry status characteristics with us. Dress, things we place on our clothing, the kinds of shoes we wear, hairstyling, the backpacks we carry, the people we hang with, all these things ( and so many more ) are signs for others to assign status to us. Status is a normal part of life. It makes no difference really until a task that requires a particular outcome appears. Tasks such as these are the stuff of schools.

2. Task Appears.

Let’s say your teacher assigns a complicated math problem to the class and gives the class an opportunity to choose two other people to work with to solve the problem. Let’s say the teacher also says something like, “The first group to finish correctly is exempted from doing the rest of the homework for the weekend.” What’s the first thing you do?

3. Activation of Expectations.

My hunch is you look around for two other people to work with that will help you successfully complete the task. And you may look for people to work with regardless of whether or not they are your close friends. The naming of a task snaps the general status characteristics that abound in human groups into a particular focus, and people who have academic status (and to some degree high peer status) become valued participants. In EST language, the task activates a set of expectations regarding who is thought to be good math problem solvers and who is not. Suddenly, there’s a status order in the class based on the perception of who will do well and who won’t.

4. Behavior Results.

There’s a shuffle while you and your classmates choose partners. You end up in a group with one friend, also a good mathematician. The other person in the group is not all that familiar to you. You know they often need extra help in math. You and your friend basically work out the problem by yourselves and because your friend is good at what he does, your conversation carries the day and you are able to successfully explain your approach to your class.

5. Status Intervention Treatments.

The above scenario is business as usual before Cohen. If Elizabeth had been your teacher, she’d have done a few things differently. She would have made sure that there were more than one way to do the task; in this case she might have asked your group, now expanded by one, to model your answer using Cuisenaire Rods. She would also have made very clear at the onset of your group work that it was going to take more than just good number sense to do this problem. She certainly would have said that using manipulatives, building models, and putting number problems into everyday situations were other ways to be smart about this task, that everyone has some abilities and not everyone has all the abilities necessary to do good work of this kind. Finally, she would have noted to the group when one of the quieter members started to fiddle around with the rods that constructing a solution using the rods was key to getting an appropriate answer. If she had done these things, you would have been less sure of yourself and more willing to listen to the input from other members of the group. After all, the teacher was still looking for a group solution, a solution you had all helped each other come to.

6. Behavior Results.

If Elizabeth had been your teacher, and if you had been invested in arriving at a solution along with your buddies, the quality of conversation would have risen in the group. There would have been more directed activity (the cards) at arriving at the solution and then arriving at an appropriate representation of that solution. Someone watching you would have seen much more talk from every member of the group, talk that was focused on the problem and talk that carried content learning. Everyone’s thinking would have deepened. If the teacher had tested you in the way you had learned to represent this problem, everyone would have demonstrated higher rates of achievement..

Dewey’s Wisdom

These are a series of quotes I’ve collected from three of Dewey’s works, two very well known, one more obscure. Collectively, they capture an essence of what this man’s thinking was all about.

(d&e) Democracy and Education, 1925

(e&e) Experience and Education, 1928

(sit) Schools of Tomorrow, 1915

*1. Social control of individuals rests upon the instinctive tendency of individuals to imitate or copy the actions of others. The latter serve as models. The imitative instinct is so strong that the young devote themselves to conforming to the patterns set by others and reproducing them in their own scheme of behavior. 40 d&e

*2. We do not have to draw out or educe positive activities from a child, as some educational doctrines would have it. Where there is life, there are already eager and impassioned activities. Growth is not something done to them; it is something they do. 50 d&e

*3. Emphasis upon the value of the early experiences of immature beings is most important, especially because of the tendency to regard them as of little account. But these experiences do not consist of externally presented material, but of interaction of native activities with the environment which progressively modifies both the activities and the environment. 93 d&e

*4. In order to have a large number of values in common, all the members of the group must have an equitable opportunity to receive and to take from others. There must be a large variety of shared undertakings and experiences. Otherwise, the influences which educate some into masters, educate others into slaves. And the experience of each party loses in meaning when the free interchange of varying modes of life experience is arrested. A separation into a privileged and a subject class prevents social interchange. 98 d&e

5. The evils thereby affecting the superior class are less material and less perceptible, but equally real. Their culture tends to be sterile, to be turned back to feed on itself; their art becomes a showy display and artificial; their wealth luxurious; their knowledge overspecialized; their manners fastidious rather than humane. 98 d&e

*6. Upon the educational side, we note first that the realization of a form of social life in which interests are mutually interpenetrating, and where progress, or readjustment, is an important consideration, makes a democratic community more interested than other communities have cause to be in deliberate and systematic education. …Since a democratic society repudiates the principle of external authority, it must find a substitute in voluntary disposition and interest; these can be created only by education. 101 d&e

7. It also follows that all thinking involves a risk. Certainty cannot be guaranteed in advance. The invasion of the unknown is of the nature of an adventure; we cannot be sure in advance. The conclusions of thinking, till confirmed by the event, are, accordingly, more or less tentative or hypothetical. Their dogmatic assertion as final is unwarranted, short of the issue, in fact. 174 d&e

*8. Study of mental life has made evident the fundamental worth of native tendencies to explore, to manipulate tools and materials, to construct, to give expression to joyous emotion, and so on. When exercises which are prompted by these instincts are a part of the regular school program, the whole pupil is engaged, the artificial gap between life in school and out is reduced, motives are afforded for attention to a large variety of materials and processes distinctly educative in effect, and cooperative associations which give information a social setting are provided. 228 d&e

9. Regarding freedom, the important thing to bear in mind is that it designates a mental attitude rather than external unconstraint of movements, but that this quality of mind cannot develop without a fair leeway of movements in exploration, experimentation, application, and so on. 357 d&e

*10. A primary responsibility of educators is that they not only be aware of the general principle of the shaping of actual experience by environing conditions, but that they also recognize in the concrete what surroundings are conducive to having experiences that lead to growth. Above all, they should know how to utilize the surroundings, physical and social, that exist so as to extract from them all that they have to contribute to building up experiences that are worthwhile. Traditional education did not have to face this problem; it could systematically dodge this responsibility. 40 e&e

11. I am not romantic enough about the young to suppose that every pupil will respond or that any child of normally strong impulses will respond on every occasion. There are likely to be some who, when they come to school, are already victims of injurious conditions outside of the school and who have become so passive and unduly docile that they fail to contribute. There will be others who, because of previous experiences, are bumptious and unruly and perhaps downright rebellious. But it is certain that the general principle of social control cannot be predicated upon such cases. It is also true that no general rule can be laid down for dealing with such cases. The teacher will have to deal with them individually. 56 e&e

*12. It is not enough to insist upon the necessity of experience, nor even of activity in experience. Everything depends upon the quality of the experience which is had. …Hence, the central problem of education based upon experience is to select the kind of present experiences that live fruitfully and creatively in subsequent experiences. 28 e&e

13. Education which ignores this viral impulse furnished by the child, is apt to be “academic,” “abstract,” in the bad sense of such words. If textbooks are used as the sole material, the work is much harder for the teacher, for besides teaching everything herself she must constantly repress and cut off the impulses of the child toward action. 73 sot

14. No book or map is a substitute for personal experience; they cannot take the place of the actual journey. The mathematical formula for a falling body does not take the place of throwing stones or shaking apples from a tree. 74 sot

15. In another building all the pupils above the fourth grade have organized into civic clubs. They divided the school district into smaller districts and one club took charge of each district, making surveys and maps of their own territory, counting lamp posts, alleys, and garbage cans, and the number of policemen, or going intensively into the one thing which interested them most. They each club decided what they wanted to do for their own district and set out to accomplish it, whether it was the cleaning up of a bad alley or the better lighting of a street. 82 sot

16. A truly scientific education can never develop so long as children are treated in the lump, merely as a class. Each child has a strong individuality, and any science must take stock of all the facts in its material. Every pupil must have a chance to be who he truly is, so that the teacher can find out what he needs to make him a complete human being. 137 sot

17. But if every pupil has an opportunity to express himself, to show what are his particular qualities, the teacher will have material on which to base her plans of instruction. Since a child lives in a social world, where even the simplest act or word is bound up with the words and acts of his neighbors, there is no danger that this liberty will sacrifice the interests of others to caprice. Liberty does not mean the removal of the checks which nature and man impose on the life of every individual in the community. 138 sot

*18. We send children to school supposedly to learn in a systematic way the occupations which constitute living, but to a very large extent, the schools overlook, in the methods and subject-matter of their teaching, the social basis of living. Instead of centering the work in the concrete, the human side of things, they put the emphasis on the abstract, hence the work is made academic – unsocial. 165 sot

*19. There are three things about the old-fashioned school which must be changed if schools are to reflect modern society: first, the subject-matter, second, the way the teacher handles it, and third, the way the pupils handle it. 170 sot

20. Our world has been so tremendously enlarged and complicated, our horizons so widened and our sympathies so stimulated, by the changes in our surroundings and habits brought about by machinery, that a school curriculum which does not show this same growth can be only very partially successful. The subject-matter of the schoolroom must be enlarged to take in the new elements and needs of society. 171 sot

*21. Hence, the daily experiences of the child, his life from day to day, and the subject matter of the schoolroom, are parts of the same thing; they are the first and last steps in the life of a people. To oppose one to the other is to oppose the infancy and maturity of the same growing life; it is to set the moving tendency and the final result of the same power over against each other; it is to hold that the nature and the destiny of the child war with each other. 71 sot

*22. It is fatal for a democracy to permit the formation of fixed classes. Differences of wealth, the existence of large masses of unskilled laborers, contempt for work with the hands, inability to secure the training which enables one to forge ahead in life, all operate to produce classes, and to widen the gulf between them. …The only fundamental agency for good is the public school system. Every American is proud of what has been accomplished in the past in fostering among very diverse elements of population a spirit of unity so that the sense of common interests and aims has prevailed over the strong forces working to divide our people into classes. 314 sot

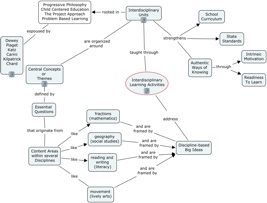

Interdisciplinary Teaching in a Standards-Obsessed Environment

Our internship supervisors have been meeting to create a more rational explanation for Unit Plan expectations. Of course our schema for the abstractions of essential questions, big ideas, topics, themes, disciplines, assessments, grade level equivalents, etc. (ad nauseum?) crashed together in a delightfully challenging mix. Here’s one big picture I offer through the good graces of CMAPing. Clicking on the smaller image will get you a larger jpeg!

You can also access through my Interdisciplinary Unit weblink.

A Blast From The Past: Ray, Jerry, and Fats

Sent to me my an old friend. You gotta hear it to believe it! The video was made in 1986 at a New Orleans nightclub. Included in the group are Rod Stewart, Rod Wood from the Stones, and Phil Shaffer, producer. Have fun. If you don’t start groovin’ with this, I would definitely recommend motion therapy!

Not Having Enough…Teaching Kids Across The Economic Chasm

November’s Teaching Tolerance newsletter is powerful with respect to working with kids whose families can’t “get ahead.” After seeing on the news the other night that 93+% of children attending public school in Louisiana are under federal poverty guidelines, this article takes on special significance.

Why don’t we get angrier about the state of affairs in this country?

Rigor + Support = Success

One-sixth of American children live in poverty. Experienced teachers offer a formula for change.

by Jeff Sapp

According to the Children’s Defense Fund, 17.6 percent of this nation’s children live in poverty — about one of every six children. The numbers are rising, and, alarmingly, the number of children living in extreme poverty — families with incomes at or below 50 percent of the poverty line — is rising even more dramatically. They live in cities, towns and rural areas. More than 30 rural counties in 11 states, for example, have poverty rates higher than the poorest big cities. Other factors also come into play, including race and ethnicity, class and immigration status. Fifty-eight percent of children of immigrant families, for example, live in low-income families, compared with 35 percent of children of native-born families.

Teaching in Poverty

Some teachers find themselves teaching impoverished children by happenstance. Others have been recruited, with various incentives, specifically to work in high-poverty areas. But are they equipped to teach children in poverty? And what might help them succeed? Teaching Tolerance visited three schools that successfully work with children from impoverished backgrounds. Educators in each school offer a glimpse of what works.

Some have created their own programs. Others draw from established programs. In the end, their words echo each other, focusing on the motto of Advancement Via Individual Determination, or AVID, a school-based academic support program for grades 5 through 12: Rigor plus support equals success.

Rigor.

Support.

Success.

Not the words usually uttered when people speak of children in poverty. And maybe that’s part of the problem.

A Rigorous Road

Consider rigor, the first factor in the AVID equation: Students from impoverished backgrounds need structure, routine, challenging work and rigorous demands.

“We’re blunt in AVID,” says Katherine Dooley of Orange Glen High School in Escondido. “Education is a way out of poverty. The goal is that you’re going to get into a four-year university, and that is going to change your life.”

Repetition, too, plays a vital role. It took Dooley some time to learn that lesson, feeling frustrated on the third and fourth times she’d repeat instructions and a student still wasn’t getting it.

“Finally I just began repeating it four, five, six and even seven times until they did,” she says.

Another sign of rigor: Dooley links AVID students with gifted and talented students in the same courses. “AVID students need socialization. Left alone, they use a very informal discourse with me like, ‘Yeah.’ I tell them they need to say, ‘Yes.’ I want to build their cultural capital. I owe them that as much as knowing the derivative of something.”

Of the eleven AVID teachers at Orange Glen, six are Advanced Placement teachers, including Dooley, who teaches AP calculus. This, Dooley feels, is another important tenet of working with children in poverty.

“You don’t lie to them,” she says. “(You) tell them it is very hard work.”

Rigor, too, is at the core of TAAS’s success. At the school for homeless teens in San Diego, curriculum is not limited to math, science and the arts; an array of social rules and behavioral expectations complements the more conventional academic challenges. Student success in abiding by school rules is rewarded with points they can use to purchase items in the school store.

“The rules and structure are important because typically people who are homeless live in a world void of structure,” says Scott Gross, who facilitates community trainings on poverty for The Village Training Institute in San Diego. “To be successful in society, people need to be able to operate in structured environments. TAAS gives students an opportunity to practice that structure.”

The Structure of Support

On any given day at West Powellhurst Elementary in Oregon, 10 parents speaking three different languages can be found reading to kids in the library. This is Raisa Balashov’s English Language Learner Parent Read Aloud Program, now in its sixth year. The program encourages parent partnerships with the school, involving families in their children’s educations. “Relationships are paramount,” Balashov says.

The reading program is just one of the supports the school offers. Others help impoverished students learn skills and rules they’ll encounter in the professional world:

• In Jason Adam’s 1st-grade classroom, a stuffed dinosaur serves as a “talking stick.” Only the student holding the dinosaur is allowed to speak, helping children develop more formal social skills.

• In Annie Falconer’s 2nd-grade class, students use an appointment book to pair up for group work. Guided encouragement also helps students improve social behaviors. When Sina is bothering her neighbor, for example, Falconer calmly says, “Sina, can you make a better decision right now?” Teachers never raise their voices to students at West Powellhurst, another model of respect.

• In Meghan McLaughlin’s 4th-grade classroom, students make presentations about what they have learned over the course of the school year. In response, classmates fill out slips of paper giving them kind, specific feedback. Feedback sentences begin with such phrases as, “Perhaps maybe next time you could…” or “It was helpful to me when you…”

For Dooley, at Orange Glen in Escondido, Calif., support starts before the first bell rings and doesn’t end when the final bell sounds.

“I keep my room open late because they can do their homework in here with me,” she says. “This space is important for that reason. Also, I teach them to work in groups so that they can help and tutor each other. And that’s just what happens in the late afternoons in here. Students are in cooperative groups, naturally tutoring each other. They only come to me if they’ve exhausted all other resources.”

In reiterating AVID’s higher-education goal, teachers talk bluntly with students about what obstacles stand in their way. Dooley asks students, “What’s your biggest obstacle now? And what are solutions to get past it?” Dooley constantly helps students understand they are in charge of their lives.

As Dooley speaks about overcoming obstacles, a student named Jesus bursts into the classroom. A senior, he’s there to tell Mrs. Dooley that he just received another scholarship, bringing his total to $20,000. He is off to Berkeley in the fall.

Earlier, a former student of Dooley’s dropped by for a visit. He had just finished his second year at Chico State. He and Dooley gave each other a big hug. “Are you getting smarter?” she asked. “Yes,” he replied. “I told you that you would!” she exclaimed.

At TAAS in San Diego, Jeff Heil is frustrated when he sees adults lower academic expectations for his students because they are homeless.

“Our students need safety, respect and high expectations,” Heil says. “They don’t need charity, but opportunity.”

Celebrating Success

Given such opportunity, TAAS students excel.

The school is gaining a reputation as a hotbed of aspiring filmmakers. Two years ago, a TAAS student-produced film, Runaway, ran away with the grand prize at the San Diego County Innovative Video in Education competition. The film went on to garner a nomination in the 2003 Syracuse International Film Festival. This spring, another film, Shadow, written and produced by a TAAS student, received the iVIE award in the Social Issues category.

Bolstered by success in a competition that draws entries from wealthy school districts, TAAS students learn that drive and intelligence are not tied to socio-economic class.

That’s true at West Powellhurst, too, where students’ reading test scores are off the charts. In April 2005, the school won a Celebrating Student Success Award as one of 12 schools in Oregon that over-achieve. Ninety-five percent of the children in the school — including ESL students — passed the state 3rd-grade test. Typical scores of other schools in Portland run in the low 80s.

In the end, the underpinnings of teaching students in poverty are the hallmark of any good educator: create an emotionally safe environment where students have a sense that the classroom is a family, and offer academically rigorous school work with the structure that supports success. For educators working with children in poverty, these cornerstones need to be firmly and deliberately laid.

Dooley sent 56 seniors off to a new future last year. She hopes the ripple will be felt by the world. “I always urge them to get out and vote,” she says. “Be political! And remember when the revolution comes, I was on your side.”

A poster quoting Cesar Chavez in Heil’s room supports the concept of revolution as well:

“Once social change begins, it cannot be reversed. You cannot un-educate the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. You cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore.”

>> POVERTY LESSON FOR TEACHERS

Go (http://www.tolerance.org/teach/activities/activity.jsp?ar=651)

>> RESOURCES

The Toussaint Academy. (http://www.toussaintacademy.org)

AVID Supporters Help Students Find Success

by Jeff Sapp

When Orange Glen High School’s demographics shifted from middle-class to poor, Katherine Dooley and a handful of her colleagues in Escondido, Calif., teamed with AVID, a local program that has now gone national.

One of AVID’s most impressive indicators of success is the rate at which it sends students to four-year colleges. More than 70 percent of AVID students were accepted into four-year colleges last year.

How is it possible that AVID succeeds so dramatically?

“Constant connection,” Dooley says.

AVID teachers don’t just see students for an hour and a half a couple times a week. AVID students are with Dooley every single day for four years.

“This long-term connection with kids … is an integral part of helping them succeed,” she says. Dooley sees students supporting each other emotionally, tutoring each other academically and spending considerable time in her classroom.

This safe space is vital for student success. “They live in here,” she says.

Happy Birthday, Dr. Dewey

Dewey’s way of placing human activity at the center of his theorizing has always been inspirational to me. I assembled a list of quotes that I sometimes have students read when we visit his memorial at UVM. They continue to ring so true. Here they are, in honor of his birthday, October 20, 1859. Burlington, VT.

Quotes: John Dewey

1859-1952

Democracy and Education, 1925

Experience and Education, 1928

Schools of Tomorrow, 1915

*1. Social control of individuals rests upon the instinctive tendency of individuals to imitate or copy the actions of others. The latter serve as models. The imitative instinct is so strong that the young devote themselves to conforming to the patterns set by others and reproducing them in their own scheme of behavior. 40 d&e

*2. We do not have to draw out or educe positive activities from a child, as some educational doctrines would have it. Where there is life, there are already eager and impassioned activities. Growth is not something done to them; it is something they do. 50 d&e

*3. Emphasis upon the value of the early experiences of immature beings is most important, especially because of the tendency to regard them as of little account. But these experiences do not consist of externally presented material, but of interaction of native activities with the environment which progressively modifies both the activities and the environment. 93 d&e

*4. In order to have a large number of values in common, all the members of the group must have an equitable opportunity to receive and to take from others. There must be a large variety of shared undertakings and experiences. Otherwise, the influences which educate some into masters, educate others into slaves. And the experience of each party loses in meaning when the free interchange of varying modes of life experience is arrested. A separation into a privileged and a subject class prevents social interchange. 98 d&e

5. The evils thereby affecting the superior class are less material and less perceptible, but equally real. Their culture tends to be sterile, to be turned back to feed on itself; their art becomes a showy display and artificial; their wealth luxurious; their knowledge overspecialized; their manners fastidious rather than humane. 98 d&e

*6. Upon the educational side, we note first that the realization of a form of social life in which interests are mutually interpenetrating, and where progress, or readjustment, is an important consideration, makes a democratic community more interested than other communities have cause to be in deliberate and systematic education. …Since a democratic society repudiates the principle of external authority, it must find a substitute in voluntary disposition and interest; these can be created only by education. 101 d&e

7. It also follows that all thinking involves a risk. Certainty cannot be guaranteed in advance. The invasion of the unknown is of the nature of an adventure; we cannot be sure in advance. The conclusions of thinking, till confirmed by the event, are, accordingly, more or less tentative or hypothetical. Their dogmatic assertion as final is unwarranted, short of the issue, in fact. 174 d&e

*8. Study of mental life has made evident the fundamental worth of native tendencies to explore, to manipulate tools and materials, to construct, to give expression to joyous emotion, and so on. When exercises which are prompted by these instincts are a part of the regular school program, the whole pupil is engaged, the artificial gap between life in school and out is reduced, motives are afforded for attention to a large variety of materials and processes distinctly educative in effect, and cooperative associations which give information a social setting are provided. 228 d&e

9. Regarding freedom, the important thing to bear in mind is that it designates a mental attitude rather than external unconstraint of movements, but that this quality of mind cannot develop without a fair leeway of movements in exploration, experimentation, application, and so on. 357 d&e

*10. A primary responsibility of educators is that they not only be aware of the general principle of the shaping of actual experience by environing conditions, but that they also recognize in the concrete what surroundings are conducive to having experiences that lead to growth. Above all, they should know how to utilize the surroundings, physical and social, that exist so as to extract from them all that they have to contribute to building up experiences that are worthwhile. Traditional education did not have to face this problem; it could systematically dodge this responsibility. 40 e&e

11. I am not romantic enough about the young to suppose that every pupil will respond or that any child of normally strong impulses will respond on every occasion. There are likely to be some who, when they come to school, are already victims of injurious conditions outside of the school and who have become so passive and unduly docile that they fail to contribute. There will be others who, because of previous experiences, are bumptious and unruly and perhaps downright rebellious. But it is certain that the general principle of social control cannot be predicated upon such cases. It is also true that no general rule can be laid down for dealing with such cases. The teacher will have to deal with them individually. 56 e&e

*12. It is not enough to insist upon the necessity of experience, nor even of activity in experience. Everything depends upon the quality of the experience which is had. …Hence, the central problem of education based upon experience is to select the kind of present experiences that live fruitfully and creatively in subsequent experiences. 28 e&e

13. Education which ignores this viral impulse furnished by the child, is apt to be “academic,” “abstract,” in the bad sense of such words. If textbooks are used as the sole material, the work is much harder for the teacher, for besides teaching everything herself she must constantly repress and cut off the impulses of the child toward action. 73 sot

14. No book or map is a substitute for personal experience; they cannot take the place of the actual journey. The mathematical formula for a falling body does not take the place of throwing stones or shaking apples from a tree. 74 sot

15. In another building all the pupils above the fourth grade have organized into civic clubs. They divided the school district into smaller districts and one club took charge of each district, making surveys and maps of their own territory, counting lamp posts, alleys, and garbage cans, and the number of policemen, or going intensively into the one thing which interested them most. They each club decided what they wanted to do for their own district and set out to accomplish it, whether it was the cleaning up of a bad alley or the better lighting of a street. 82 sot

16. A truly scientific education can never develop so long as children are treated in the lump, merely as a class. Each child has a strong individuality, and any science must take stock of all the facts in its material. Every pupil must have a chance to be who he truly is, so that the teacher can find out what he needs to make him a complete human being. 137 sot

17. But if every pupil has an opportunity to express himself, to show what are his particular qualities, the teacher will have material on which to base her plans of instruction. Since a child lives in a social world, where even the simplest act or word is bound up with the words and acts of his neighbors, there is no danger that this liberty will sacrifice the interests of others to caprice. Liberty does not mean the removal of the checks which nature and man impose on the life of every individual in the community. 138 sot

*18. We send children to school supposedly to learn in a systematic way the occupations which constitute living, but to a very large extent, the schools overlook, in the methods and subject-matter of their teaching, the social basis of living. Instead of centering the work in the concrete, the human side of things, they put the emphasis on the abstract, hence the work is made academic – unsocial. 165 sot

*19. There are three things about the old-fashioned school which must be changed if schools are to reflect modern society: first, the subject-matter, second, the way the teacher handles it, and third, the way the pupils handle it. 170 sot

20. Our world has been so tremendously enlarged and complicated, our horizons so widened and our sympathies so stimulated, by the changes in our surroundings and habits brought about by machinery, that a school curriculum which does not show this same growth can be only very partially successful. The subject-matter of the schoolroom must be enlarged to take in the new elements and needs of society. 171 sot

*21. Hence, the daily experiences of the child, his life from day to day, and the subject matter of the schoolroom, are parts of the same thing; they are the first and last steps in the life of a people. To oppose one to the other is to oppose the infancy and maturity of the same growing life; it is to set the moving tendency and the final result of the same power over against each other; it is to hold that the nature and the destiny of the child war with each other. 71 sot

*22. It is fatal for a democracy to permit the formation of fixed classes. Differences of wealth, the existence of large masses of unskilled laborers, contempt for work with the hands, inability to secure the training which enables one to forge ahead in life, all operate to produce classes, and to widen the gulf between them. …The only fundamental agency for good is the public school system. Every American is proud of what has been accomplished in the past in fostering among very diverse elements of population a spirit of unity so that the sense of common interests and aims has prevailed over the strong forces working to divide our people into classes. 314 sot

Podcasting for Learning

Students Thinking

I felt crummy about the sharing I’d done at the faculty workshop. Asked to present my work with Podcasting, I told my interested colleagues that I was a “sometimes user” of the technology. Why sometimes? Well, I needed to be convinced that the work that went into creating a podcast was worth the effort. And for me, an education professor of an embarassingly long number of years, “worth” means high quality learning – personal understanding and depth, not just acquisition of someone else’s knowledge. I needed to be convinced that aside from having a good time with a new technology – I love the challenge of just getting the stuff to work while 35 pairs of eyes hold you accountable – my students were actually learning more and better than they would in a more conventional task.

This little essay is about my next steps and how I’ve come to understand and see that different, and yes, better learning is happening. I’ve figured some things out.

My class is a first year required 8am in the morning two days a week introduction to learning theory for maybe-teachers-to-be. It is my personal wish that the students who walked through the door on day one wanting to be a teacher emerge from my class more psyched than ever, and more real in terms of their perceptions about what their future classrooms of children will call upon them to do. It is my personal wish that the students who walked through the door on day one not so sure they wanted to be a teacher at least emerge from my cocoon clearer in their vision of who they might be and more informed of what the profession will call upon them to do. For all my students I wish they realize they are not the center of this universe and that they must appreciate the similarities and differences in the people who populate the world around them. I want them to know that being a teacher in the 21st century will call upon them to more skillful than any generation of teachers coming before them. Finally, I want all my collegiates to be able to articulate how all students “learn in the same way” as a way of developing an informed perspective on that potential cop-out phrase, “Well, all students learn differently.”

It’s a form and content issue for me. I do believe we all learn differently when it comes to the content of our lives, lives that have populated our conceptual structures. I also think that those conceptual structures of prior knowledge get built in pretty much the same way for all of us, biologically speaking. Our learning process is a whole lot more similar than it is different. At least that’s the mantra I want to discomfort their lives with two days a week at 8 in the morning. Did I mention that already?

So, where does Podcasting and learning enter this picture? As my bridge to understanding the similarities of learning of all human beings, we dig into James Zull’s The Art of Changing The Brain right off the bat. And for purposes of this little essay, I want to immediately narrow to my point. After spending some time describing how the brain works, and how that working can be described quite nicely through the descriptive learning cycle research of Kolb, Zull begins to deepen the reader’s understanding of how the rear integrative cortex and the frontal integrative cortex work to structure active thought and action from prior knowledge. Of the writers use of image and text, he notes the “unskilled use of language by the learner is one of the greatest challenges for the teacher.” Delving into the work of Robert Leamnson, he goes on to say he was “intrigued” by the idea that “insisting that students speak to him about the academic content of subject matter using complete, grammatically correct sentences.” He admonishes us that planning done by the executive functions of the prefrontal cortex (metacognitively speaking, of course) “requires learners to carefully assemble their plan for speaking. This plan must have specific content, and that content must be arranged in a way that accurately conveys the image that is in their brain. No clear image, no plan!” Here, Zull is talking about the importance of students being asked to write informational text, non-fiction text that is written to explain an idea or demonstrate understanding of a concept or set of rules or to establish connections between events or whatever. It is, as my literacy colleagues note, writing for a purpose.

Plans mean a good deal to Zull, for it is in the plan of action, the sequence of steps that helps transform prior knowledge to newer understandings through action, that understanding and comprehension get constructed. What I figured out and am about to explain, is that the Podcast requirement created a context for my students to have to plan a way to verbally explain a consolidation of big ideas and details from the chapters they were reading. Read on.

Reading Zull, especially these latter chapters, is a bit of a challenge. He writes iteratively. Having established his big ideas in the first part of his book, he goes back in the latter chapters and deepens his analysis of the relationship between what teachers and learners do and how the workings of the brain might inform the teaching / learning relationships so both teacher and learner might at the end of the day, feel they had spent good time together. I wanted my students to “get deeper” along with Zull. I’d had them meet in chapter groups, process and unpack the chapters, and take responsibility for connecting the high points by means of a webct based discussion. In short, I wanted them to achieve a deeper synthesis between the big ideas and the details.

I get the fact that students have to actively work on the ideas of our class learning and I get the fact that doing it together in class pays special benefits. It is way too important work to assume they are going to do more than just passively read their work and answer whatever assignment I put before them. If I want them to process our work, I want them to do it where I can see it and hear it and comment on it. Podcasting, on the heals of collaborative classroom discussion, extends the benefits of active learning by providing a reason for putting things together while at the same time, after the amygdala calms down, can create a little fun and laughter as well.

What I got on the webct discussion board were big ideas and details but not much synthesis. Some of why that happened might have been the way I structured the discussion, some of it might have been due to the nature of webct threaded discussions. Nevertheless, my joy in realizing my astuteness in noticing that I’d arrived at little synthesis was dulled by what I in fact noticed. My students’ prior knowledge hadn’t really been deepened by establishing more connections between the details of the chapter and the bigger ideas introduced in the first part of the book. Most of them had merely stated the big ideas, and merely stated attendant details. It was underwhelming, or in some cases, to quote the late Howard Cosell, merely whelming work.

Here’s where the podcast came into play. We spent our last class period back in those same groups. This time the classwork assignment to each group was to create one 45 second to two minute podcast that “pulled together” the information in their chapter. What I’d realized on an early morning dogwalk (1) was that unlike an individual writing assignment, the group podcast might force the synthesis they’d been unable to achieve in the group based discussion board offering. I gave them twenty minutes to review their discussion entries (which I graciously provided), plan their podcast content and presentation and then come find me. I, with my trusty iPod, iTalk microphone, and later, Garageband software, would record what they had to say, make a podcast, and place it on UVM’s iTunesU site.

The first group was ready to go in twenty minutes. They passed the iPod around and created a 1 minute 30 second synthesis of their chapter, effectively tying together detail and big idea unlike their first attempt. Each of the other four groups followed, each employing a slightly different style but each having achieved a degree of synthesis that gained a smile from their teacher. These reports ranged from whelming to overwhelming, again to quote Cosell. This was synthesis and this was deepened thought. Tenderly attached, no doubt, but Zull would have us believe, this was concrete, physical brain change.

The pressure of the Podcast forced the synthesis. In that way, the Podcast was not only a jazzy new tool, it was a tool employed as an agent of active learning, a form of learning that has had a long and occasionally controversial place in higher education (TP Msg. #818 Quick-thinks: The Interactive Lecture). Important active learning, I might add. I do understand that some students just because they have to speak into an device will be rehearsing new material in a more meaningful way than if the were to sit in a chair and “think about it” or even draw a webbed diagram. But the idea that the social conversation in the groups was directed at forcing a synthesis across the different student’s individual offerings is a powerful impetus to me to do more work with p-casting now that I have a way of understanding how it is indeed more “worthwhile” as a learning tool. I realized, “just talk” can be something quite powerfully rendered with the right directions and the right tool Granted, their work on webct might have been a really effective way of structuring a rehearsal for the final pod casting performance. Whatever. What I left feeling good about was that I’d figured out another way to scaffold my student’s understanding of content I feel deeply about. I want them to reconsider their thoughts about children’s learning capabilities, particularly those children who can so easily be stereotyped as at-risk and incapable of learning anything that’s worth very much simply because they are “different.” As new “maybe-teachers,” I want them to see all children as capable learners; this information about the biological basis of learning helps support that assertion. Many learning problems are teaching and schooling errors. But that’s a conversation for another time. Maybe the next Podcasting presentation.

Thanks for listening.

(1)

Podcast Sharing

I’ve been asked to share my humble attempts at Podcasting during a session at the Center for Teaching and Learning, Univ. of Vermont. Here’s my outline for the event.

Sharing Podcasting

C. Rathbone

CTL 8-07-42

1. not a Podcaster…can see its benefits…haven’t gotten there yet

not really sure how to manage the complexity of it

realize this is a curricular control issue for me…not sure how to negotiate the “ownership” issues yet

2. bottom line criteria

for me…

can’t add too much additional instructor time to managing the course

I have to be relatively comfortable with the technology

the technology is a tool to enhance learning – it doesn’t magically compel learning by itself

research: focused talk leading to beneficial cognitive growth ie. new neuronal networks

research: situating the podcast process in the known lives of the students

research: M = V x Pr success

research: the more personal the choice, the more likely higher value will be obtained

notice: none of these have to do with the technical aspects of creating podcasts: they are all learning issues

3. I think, therefore I dabble

Example One: boring lecture on Instructional Expertise

self conscious

mercifully short (I’d never do a pcast over 15 minutes)

used my iPod, recorded, uploaded directly into iTunes, exported and posted as mp3 file

objective: provide clarifying follow-up to a confusing classroom presentation

processed at the beginning of class next class period using mc assessment and clickers

Example Two: class reflection on Presentation by visiting professor (Paul Martin talking about his podcaster experience)

not so self conscious, more intentional

better thought through

had students use 3×5 cards to record questions, areas of investigation, prior to Paul’s visit

asked students to write responses to their questions/additional a-hahs that emerged during the talk

passed the iPod around, they recorded publicly in front of each other (9 in class 🙂 )

edited in Garageband, cutting embarrassing remarks, Uhhhs, adding a little pizzazz

pizzazz is actually important to lift the tenor of the podcast…I can get better at this

objectives:

a. focus the listening of Paul

b. make it personal

c. demonstrate ease of it all (ironic, right??)

d. force a response

e. listen to others

f. seamlessness in course http://261sm07.wikispaces.com/For+Friday+the+6th

met the criteria stated in #2: focus, situated, value and Psuccess, personalize

4. Thinking this through as a learning tool…there’s help out there and in here (CTL)

a. web commentaries Blog of Proximal Development http://www.teachandlearn.ca/blog/

b. containing the blogs 21Classes (instead of setting up feeds – I need help with that)

c. individual and/or collaborative virtue in both, not sure which way to go