In celebration of Women’s History Month, we are pleased to announce the launch of our latest digital collection, Diaries. The collection provides access to more than thirty digitized and transcribed diaries from the late eighteenth to early twentieth century, with three-fourths of the diaries authored by women.

The diaries in this collection were transcribed during the work-from-home portion of the Covid-19 pandemic by Special Collections staff (Ingrid Bower, Erin Doyle, Hannah Johnson, Sharon Thayer) and students (Ella Breed, Dorothy Dye, Ibrahim Genzhiyev, Tabitha Ireifej, Mike Maloney). In addition, transcription work on the Caroline Crane Marsh diaries built upon previous transcription work conducted by Mary Alice Lowenthal. The Special Collections team put an enormous amount of thought and effort into this work and what is now available online is a direct result of their labor along with, of course, the work of the original diarists themselves.

As a preview of the rich content you can expect to find in these diaries, below are brief descriptions of the women diarists, summaries of what they wrote about, and a sample entry from each. More detailed information is available within the online collection, along with the images and transcriptions of the diaries.

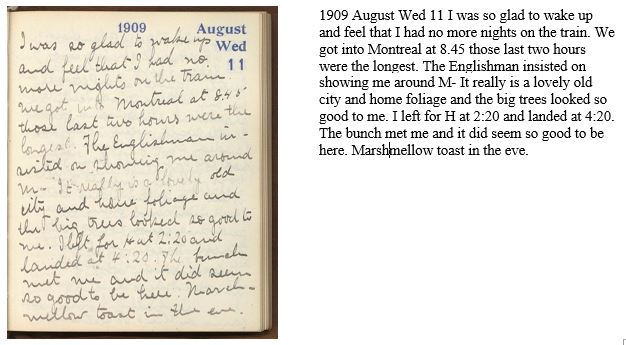

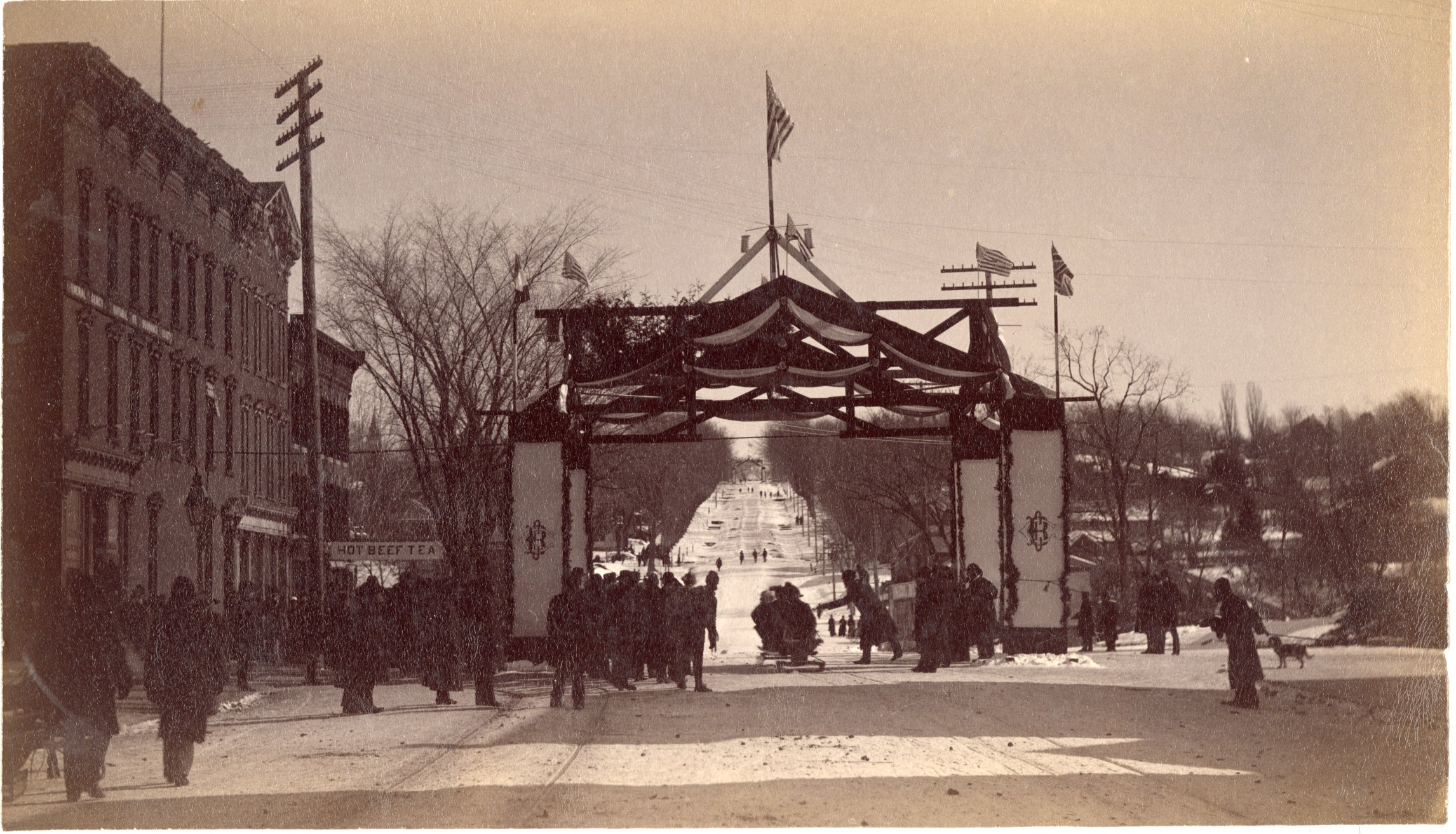

Genieve Lamson Diaries, 1908, 1909, 1910-1912

Genieve Amelia Lamson was born in Randolph, Vt. on April 29, 1887. Lamson graduated from Randolph High School in 1905. After graduation, she taught for four terms in Vermont district schools and for five years (until 1915) in high schools in Roselle Park, NJ and Springfield, Mass. Lamson completed her undergraduate and graduate studies at the University of Chicago, receiving her B.S. degree in 1920 and an M.S. in geography in 1922. She accepted a professorship at Vassar College in 1922 and taught in the geography department until her retirement in 1952.

Topics in Lamson’s diaries include teaching (as well as the process for becoming a certified teacher in Vermont circa 1910), travels to major cities of the West Coast, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle; turn-of-the-century fashion and home clothes-making, the sinking of the Titanic, turn-of-the-century slang, and the local history of Randolph, Vermont. In the passage below, Genieve writes of the last leg of her journey home, via the Canadian Pacific Railway, following a 1909 trip out west.

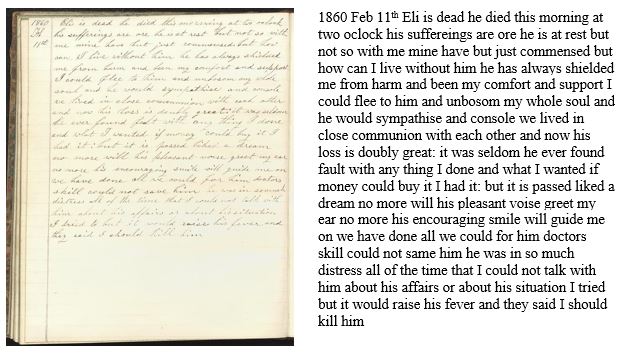

Mandana White Goodenough Diary, 1844-1846, 1860-1861

Mandana White was born on January 15, 1826 in Calais, Vermont. Between 1844 and 1845, she taught school in Marshfield and attended the Lebanon Liberal Institute in Lebanon, NH. She married Eli Goodenough in Calais on April 20, 1845, and the couple had four children that lived to adulthood: Myron Alonzo, Flora Gertrude (m. Whipple), Edward Tucker, and Charles Davis.

The Goodenoughs lived and worked on a large farm in Hardwick. After her husband’s death in 1860, Goodenough sold the family farm and purchased a smaller one in Walden, where she raised her four children. Topics in Mandana’s diary include employment opportunities for women in the 1840s, courtship and marriage, illness and death, and religious beliefs and practices in mid-nineteenth-century Vermont. Her entry for February 11, 1860, the day Eil died, is below.

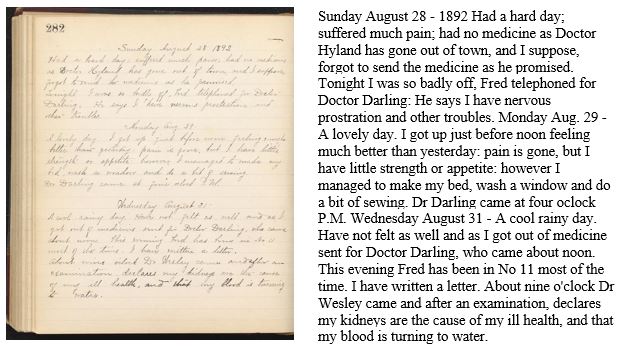

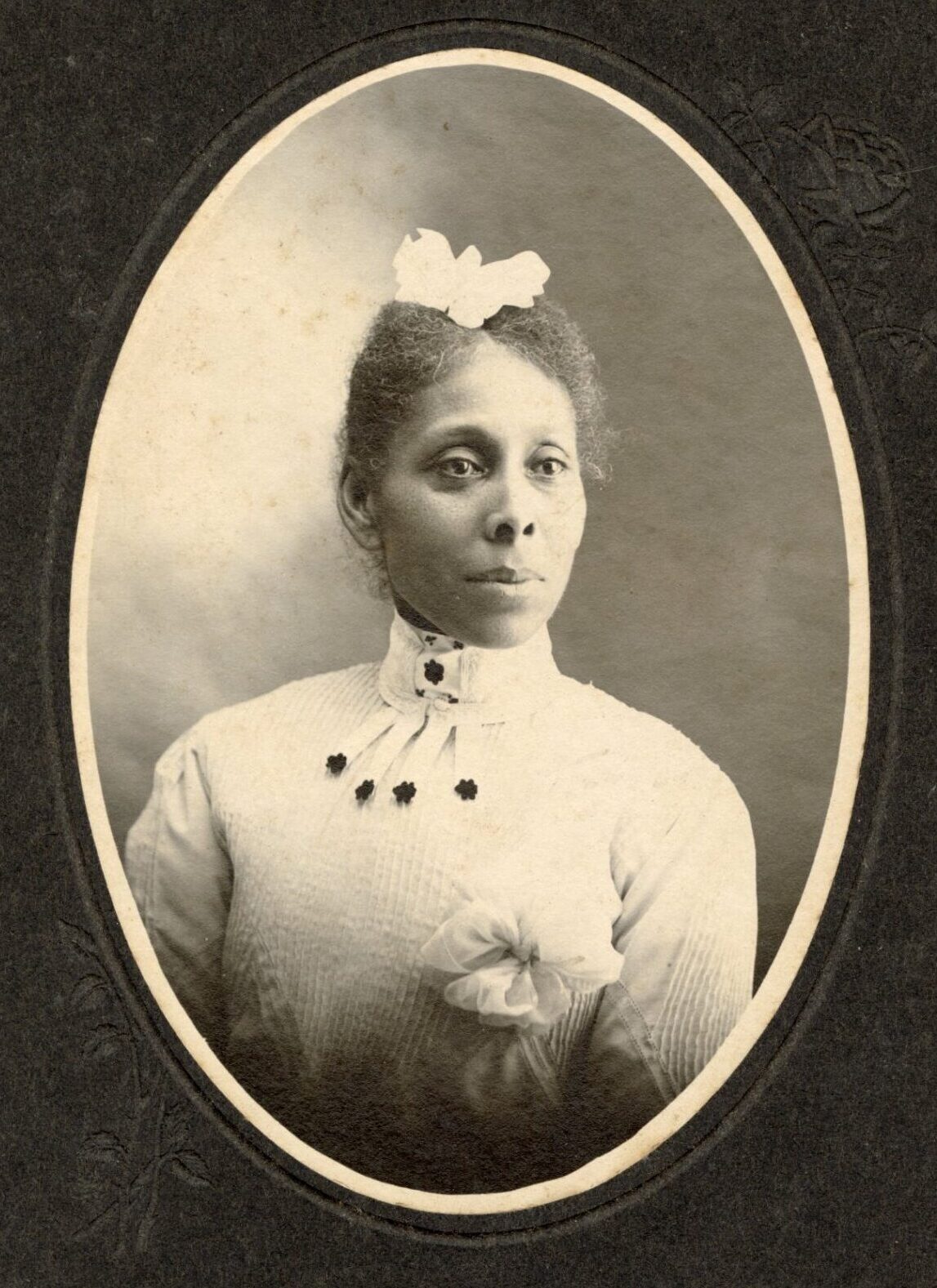

Mary Susan Davis Kelley Diary, 1883-1893

Mary Susan Davis was born on January 10, 1866 in Fairlee, Vt. Davis grew up in a large household consisting of her parents, her three siblings, and her uncle. After she graduated from secondary school in 1884, Davis helped her mother at home and with taking care of the boarders who occasionally resided in their home; she also taught in local schools and occasionally performed housework and childcare for hire in other households in the community. Prior to her first marriage, Davis moved to Orange, Massachusetts, where she was eventually employed by shoe manufacturer Jay B. Reynolds as a skiver.

Topics in this diary include women’s health and other subjects relating to health and medicine; the experiences of working women circa 1890, turn-of-the-century courtship and marriages, and the local social and cultural history of Fairlee, Vermont. A page from her diary with two entries from August 1892, where she discusses her ill health, are below.

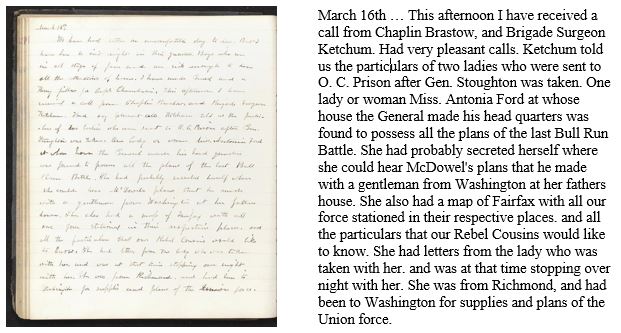

Mary Elizabeth (Johnson) Farnham was born in Bath, NH, on January 19, 1828. She came to Bradford with her parents at a young age and was educated at Bradford Academy and the Newbury Seminary. On December 25, 1849, she married Roswell Farnham (1827-1903) in St. Albans, Vermont. Farnham spent several months during the winter of 1862-63 in Union camps near Fairfax Court House and Wolf Run Shoals, VA, with her husband, who had been appointed Lieutenant Colonel and placed in command of the 12th Vermont Volunteer Regiment. Farnham returned to Vermont in April 1863 and her husband was discharged later that year, after which he entered into a career in politics.

Topics in Farnham’s diary include living conditions in Union camps and towns near the front lines, the roles and expectations of women during the American Civil War, Washington D.C. in the 1860s, mid-century modes of travel, and health and medicine during the Civil War. She writes in the March 16, 1863 passage below of some intriguing events involving the Confederate spy, Antonia Ford.

Caroline Crane was born on December 1, 1816 in Berkley, Massachusetts and was the eldest daughter of ten children. In 1839, Caroline married George Perkins Marsh (1801-1882) and in 1861, her husband was appointed U.S. Minister to the Kingdom of Italy. The couple traveled to Europe that June in the company of Caroline’s niece, Caroline “Carrie” Crane. While in Italy, the Marshes took several sightseeing trips through northern Italy, southern France, Switzerland, and western Austria. They also moved several times to stay near the capital of Italy, which moved from Turin to Florence in 1865 and then to Rome in 1873. George Perkins Marsh died in 1882 at the Marshes’ home in Vallombrosa, and Caroline returned to the United States the following year, living with her nephew Alexander Crane and other relatives until her death on October 27, 1901.

The seventeen diaries (1861-1865) included in this collection document the Marshes’ day-to-day lives during their time in Italy, particularly during their stay in Turin. Topics include the American Civil War, race and slavery, Catholicism, European political and social relations, British-American political relations, Napoleon III and Second French Empire, King Victor Emmanuel II and Italian politics, Giuseppe Garibaldi and Italian nationalism, religious and funerary practices in Italy, the status and treatment of women in Italy and elsewhere, problems within and interactions between the Italian social classes, the experiences of Protestants, Jews, and rural peasants in Italy; health and medicine in Italy, Italian industries and agricultural practices, the Italian education system, the Italian language, crime and punishment in Italy, Italian fashion and etiquette, tourism and hospitality in Italy and the Alps, popular books and reading habits during the 1860s, George Perkins Marsh’s diplomatic and scholarly activities in Italy, and the everyday experiences of upper and lower-class Italians.

In the entry below, Caroline writes of their arrival in Turin and the death of Count Camilo di Cavour, the first prime minister of the kingdom of Italy.

We are thrilled to make available these transcribed diaries on our digital collections site and, in particular, to highlight the personal accounts of these five women. In addition, we have made available for download the full-text diary transcriptions as plain text and TEI XML files: https://cdi.uvm.edu/content/diaries-transcriptions.

The online publication of these diaries represents about half of our larger diaries transcription project. Stay tuned in the coming months for the publication of an additional thirty-plus diaries from Mary Jean Simpson and two diaries from Henry Brownell from his time in Japanese-occupied China in the late 1930s.

Submitted by Chris Burns, Interim Director, Silver Special Collections