During the 2023 spring semester, Special Collections intern and History graduate student Brooke Talbott processed the records of two Burlington, Vermont women’s clubs. Drawing on correspondence, reports, minutes, scrapbooks, account books, ephemera and publications in the collections, Brooke tells the tale of the Klifa Club and the Athena Club.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the United States saw the growth of a movement that would create lasting changes within the fabric of American society. The women’s club movement, emerging alongside the suffrage movement, began in the late 1860s in Boston and New York when small groups of women formed voluntary organizations in their neighborhoods. Dedicated to the study of intellectual topics and current events, social reform and community service, these organizations defied the traditional expectations placed on women of the time. Instead of remaining at home, club members stepped into the public realm and began to shape social and political change across their communities.

At the turn of the twentieth century, hundreds of women’s clubs formed across the country. The movement made its way to Burlington, Vermont, where not one but two prominent women’s clubs were established. The Klifa Club and the Athena Club both had a lasting impact on the Burlington community.

At the turn of the twentieth century, hundreds of women’s clubs formed across the country. The movement made its way to Burlington, Vermont, where not one but two prominent women’s clubs were established. The Klifa Club and the Athena Club both had a lasting impact on the Burlington community.

Klifa Club

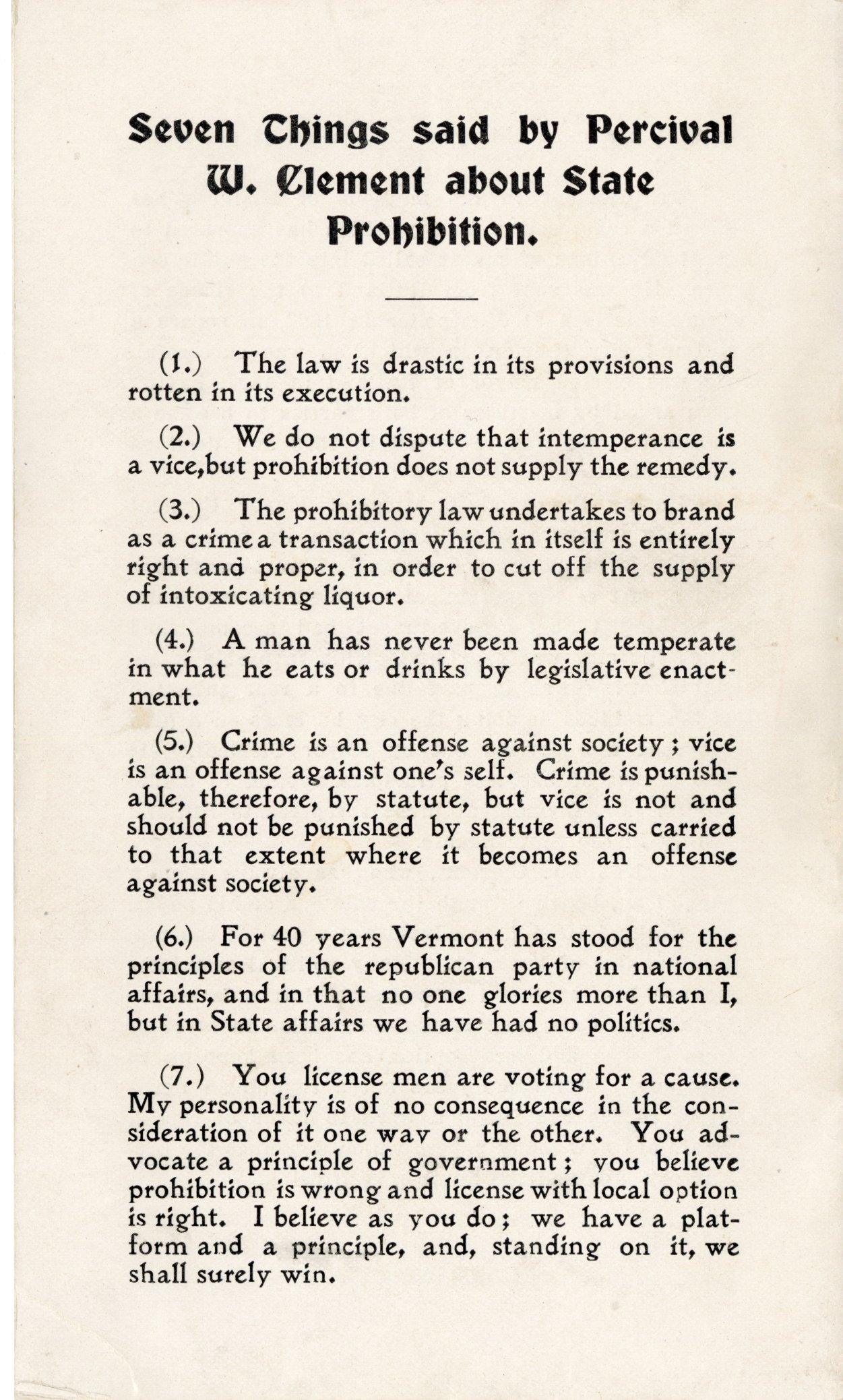

Founded in 1900, the Klifa Club was organized with the purpose of “mutual improvement of its members in literature, art, science, and the vital and social interests of the day.” The twelve founding members chose the club name from a random marking of a dictionary page. “Klifa,” the Icelandic word for “to climb,” seemed the perfect fit for the women’s group whose members would dedicate their time to the betterment of themselves and the local community.

The first meeting to discuss the formation of the club was held on October 11, 1900 in the home of Miss Mary Van Patten. At the third meeting, held on October 23, a Miss Richardson was chosen as the chair of the Governing Board. The other officers were Mary Van Patten (House Committee chair), Mary Hager (Program Committee chair), Fannie Grinnell (Entertainment Committee chair, Ada Platt (Finance Committee chair), Anna Wells (Treasurer), and Anna Pope (Secretary).

Throughout the club’s lifespan, activities were largely focused on social events. Members hosted regular afternoon teas and invited speakers. Speaker topics ranged from art, history, and psychology to nature conservancy, politics, and film. The club also participated in community events and charitable causes. In 1914, club members contributed to the adoption of a nine-hour labor law for Vermont women and children and helped raise awareness about children’s health issues in public schools.

Klifa Club member Mrs. Dimock leads a baking demonstration for workers at the Vermont Milk Chocolate Company in March 1918.

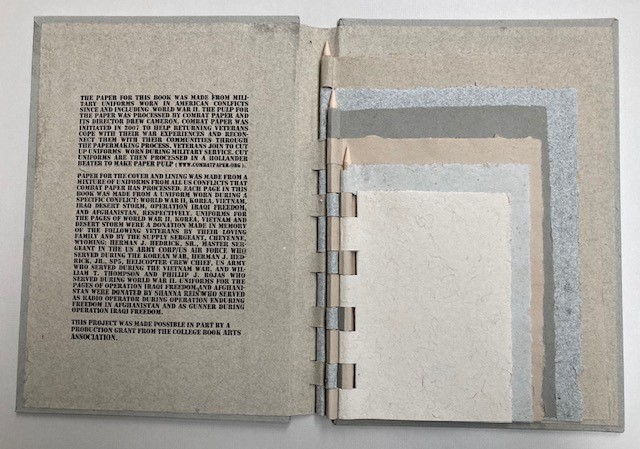

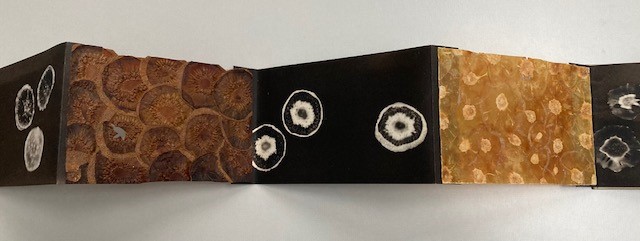

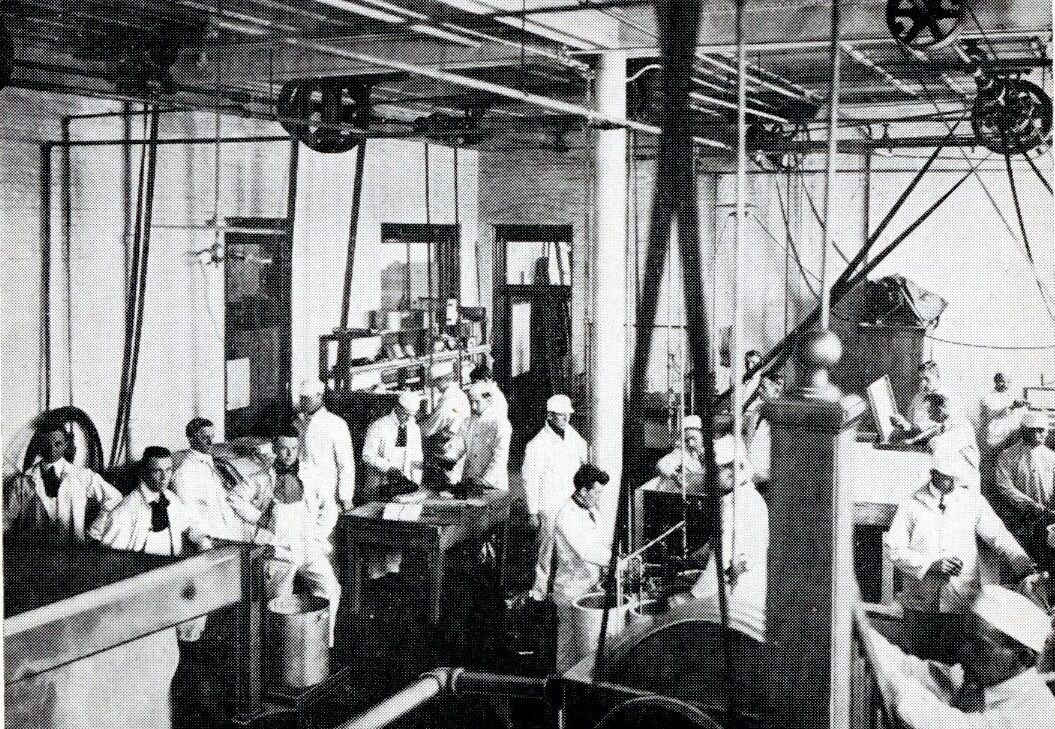

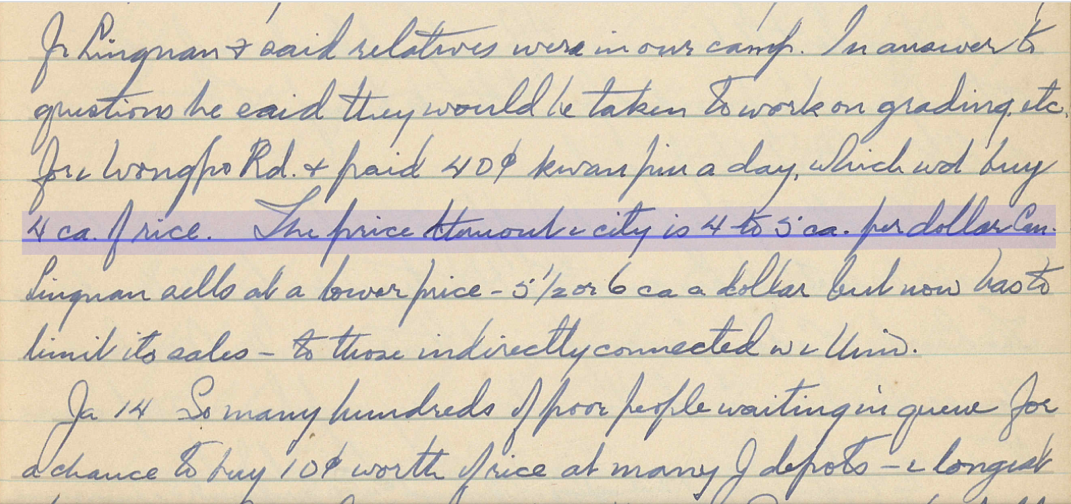

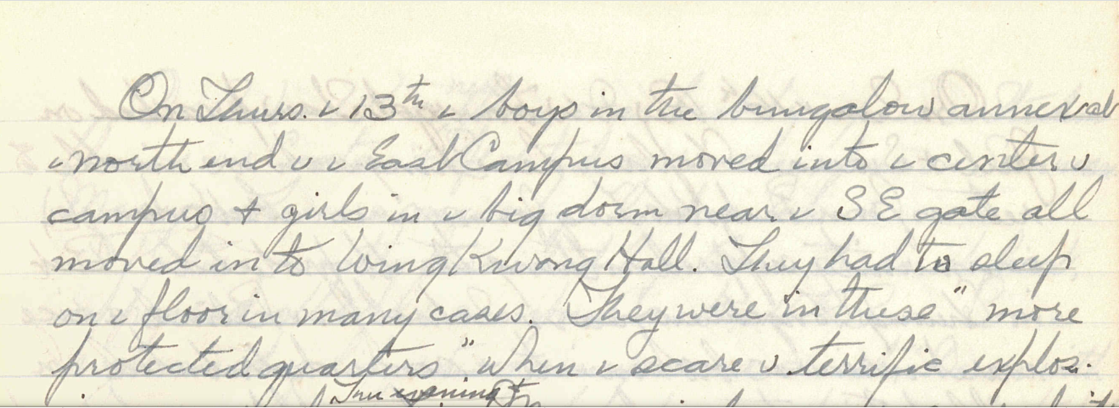

During World War I, members responded to the call to contribute to the war effort. A scrapbook includes photographs of club members at conservation events, newspaper articles detailing conservation efforts, and programs from various war-related events. In October 1917, the club voted to do away with all refreshments at meetings and social gatherings to assist in the conservation of food. Throughout 1918, the Klifa Club remained at the forefront of Burlington’s food conservation efforts. The club created a “War Breads” exhibit to educate the community on the proper preparation of wartime food, shared wartime recipes that used potatoes instead of wheat, organized conservation and cooking demonstrations for employees at the Vermont Milk Chocolate plant, the Crystal Confectionary Company and other venues. In 1919, the club continued its efforts to support the war effort, winning an award for the most artistic float in the “Welcome Home Troops” parade.

In 1924, the club acquired a building at 342 Pearl Street to use as a meeting and event space. During World War II, the club partnered with the American Red Cross by offering the home for classes in first aid, nutrition, and home nursing. Throughout the twentieth century, members continued to dedicate their time to social causes, raising money for sewing machines for home economics classes, forming a Girl Scout troop, and helping to organize the United Way and the Lund Home. Along with their regular meetings, the club frequently hosted recitals and fashion shows.

The Klifa Club occupied the building at 342 Pearl Street until July 2011, when the club closed its doors due to declining membership. By the early 2000s, club membership had deteriorated, as more and more women were employed outside the home, leading to less and less available time for women’s club meetings. The club made the decision to donate the building to the Vermont Community Foundation, which used the proceeds from the sale to create a charitable fund in the Klifa Club’s name.

Athena Club

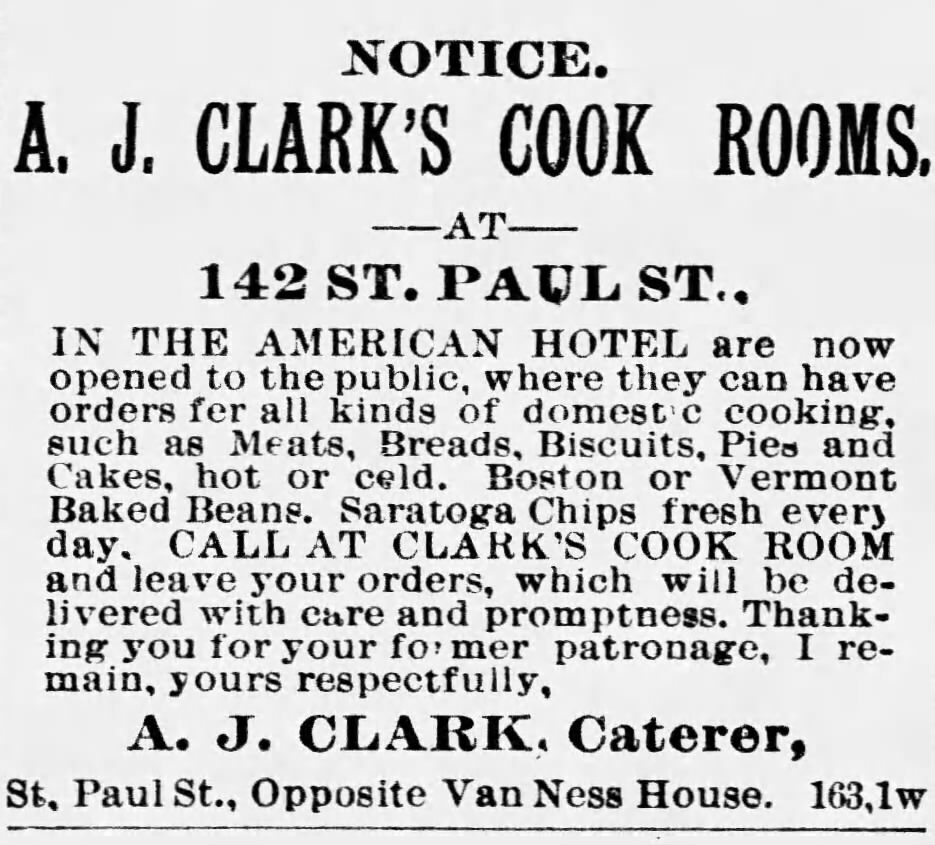

In  the fall of 1903, four women were invited to the Burlington home of Misses Ella and Bessie Brown for an afternoon of sewing, tea and conversation. The group decided to meet weekly to read together. In February 1904, while meeting at Mrs. Fred Jackson’s home, a proposal was made to form a club and invite other women to join. Later that spring, the club chose the name “Book and Thimble Club.” Membership was limited to twenty-five, with annual dues of $0.25. For an additional $0.25, members could purchase a copy of the club yearbook.

the fall of 1903, four women were invited to the Burlington home of Misses Ella and Bessie Brown for an afternoon of sewing, tea and conversation. The group decided to meet weekly to read together. In February 1904, while meeting at Mrs. Fred Jackson’s home, a proposal was made to form a club and invite other women to join. Later that spring, the club chose the name “Book and Thimble Club.” Membership was limited to twenty-five, with annual dues of $0.25. For an additional $0.25, members could purchase a copy of the club yearbook.

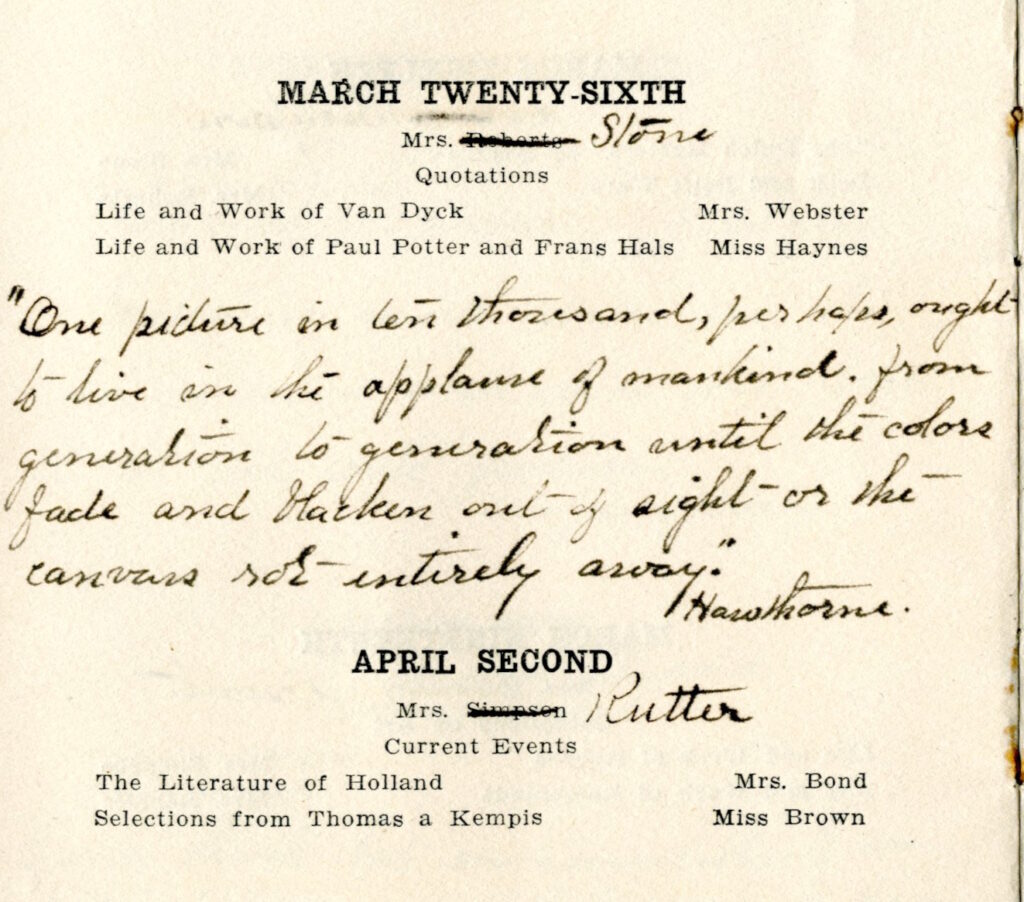

The club held weekly meetings from October to June. Meeting programs were often copied from Bay View Magazine, with topics focusing on the history and literature of France, the United States, Canada, and South America. Special celebrations were held on Christmas and Thanksgiving, as well as Lincoln’s and Washington’s birthdays.

Although an annual meeting was held each year at the President’s home, the summer of 1907 saw one of the most momentous meetings in the club’s history. In June, the club’s first real banquet was held at the Elmwood House. Eighteen members were present and contributed to the meeting program. Members approved a new name, the Athena Club, after the Greek goddess who is a patron of the arts.

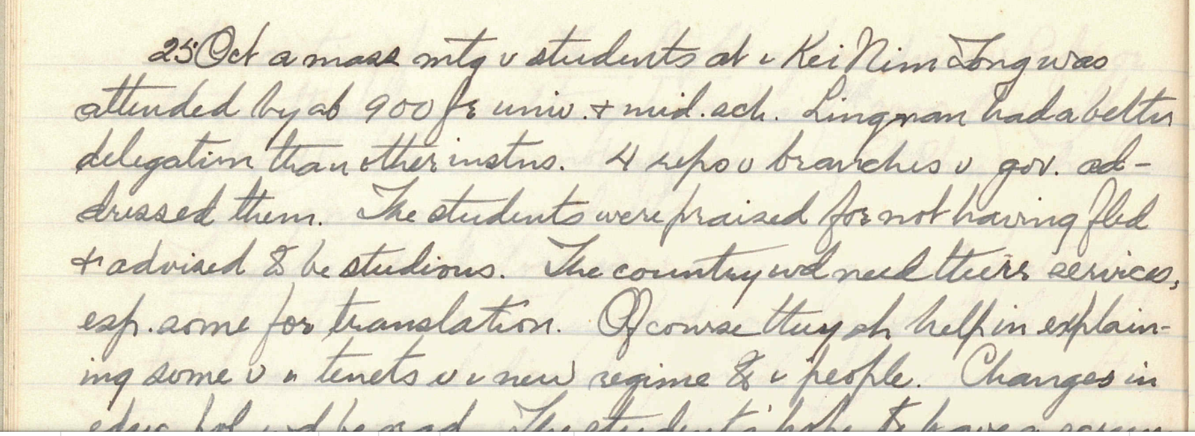

From 1904 to 1911, the Athena Club became so popular that it instituted a waiting list. In 1911, the club joined the State Federation of Women’s Clubs, signaling the club’s desire to expand its horizons. Members focused on civic service, providing scholarships, participating in charitable work during the world wars, raising money for local non-profits, and much more. Given their dedication to so many social and political causes, the club established five different departments–from music and civics to home economics and history–to keep pace with the activities.

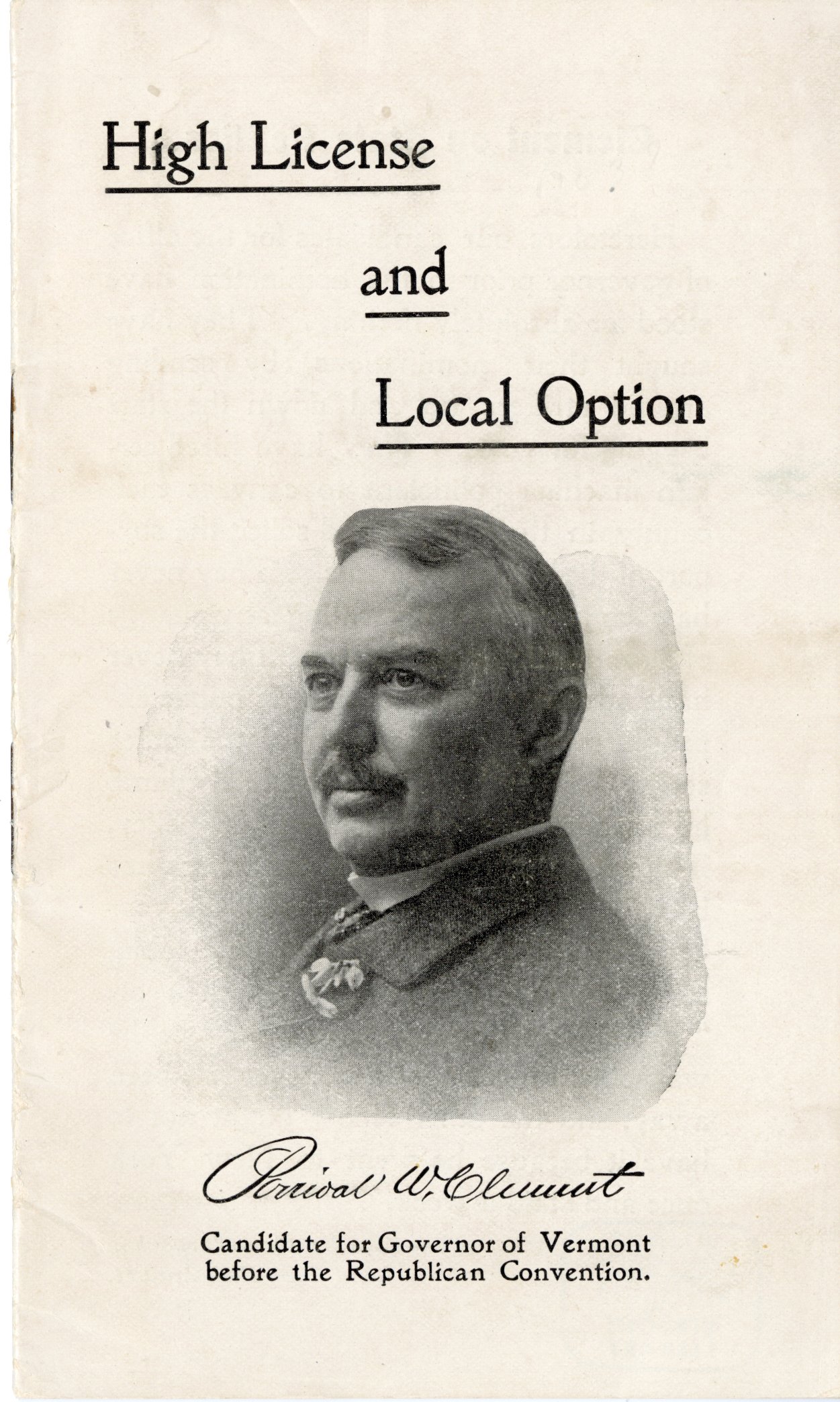

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, the Athena Club was busier than ever, growing in membership and taking part in social and political change. In 1913, members helped organize the first women’s public restroom in Vermont, with Mrs. Stone, Mrs. Hall, and Mrs. Brown working to keep the project before the city aldermen. In the years 1914-1915, members secured a placed to meet, renting the Delta Mu Society rooms in the Hayward Building. In 1918, the club pushed the city of Burlington to hire a female police officer. During World War I, members could be found taking part in Red Cross work, sewing, knitting, and contributing to the war effort in any way they could. In November 1919, Dorothy Canfield Fisher gave a lecture for members, with members’ receipts donated to Fisher’s work with French orphans.

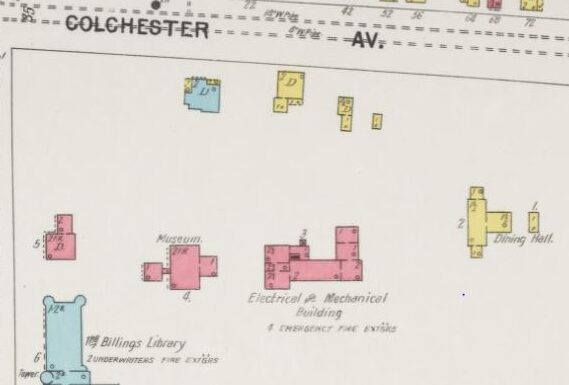

By 1925, the Athena Club’s 150 members were promoting projects that ranged from installing traffic lights to building the Burlington airport. During the spring of that year, members began to push for the purchase of a clubhouse, partly due to the fact that the Hayward Building’s two flights of stairs were difficult for members to climb. In April 1925, the club purchased 328 Pearl Street to use as a clubhouse.

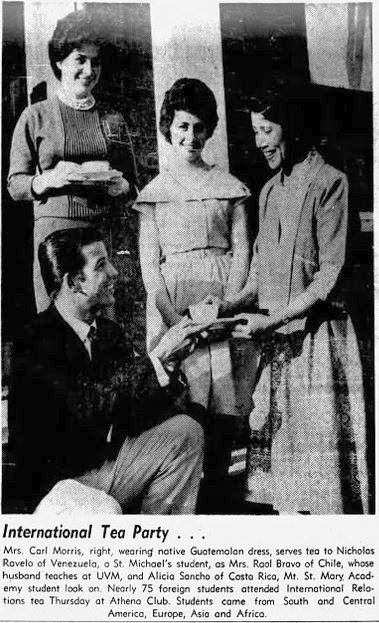

In the decades that followed, Athena Club members continued to inform themselves of state, national, and international matters. Members signed petitions against carnivals in Burlington and in favor of women jurors. Members also helped educate new voters on how to vote, worked for better housing in Burlington, and donated plants and bulbs to local schools to help beautify the city. In the 1960s, the Athena Club hosted tea parties for international university students. In, 1961, the club hosted Senator George D. Aiken at a special supper where Aiken gave a speech on foreign relations. As the Vietnam War came into the picture, members heard J. Warren McClure, the publisher of the Burlington Free Press, speak about his trip to Vietnam. Throughout this time, members also held fashion shows, rummage sales, card parties, and an annual Christmas bazaar.

By the turn of the twenty-first century, club membership had begun to decline significantly. More and more women were employed outside the home, making daytime meetings impossible to attend. In September 2003, the club donated 328 Pearl Street to the University of Vermont with an agreement that the university would sell the property and use the proceeds of the sale to create scholarships for Vermont students.

Researchers can access the inventories of the Klifa Club and the Athena Club online and contact Special Collections to view the collections in our reading room.