Tree Talk: The People and Politics of Timber

Author: Ray Raphael

Chapter Eight: Landed Forestry: A Vision for the Future

By Harry Voelkel

I read the whole of Tree Talk: The People and Politics of Timber written by Ray Raphael for this project, which along with being one of my new favorite books, has provided a lot of great background to my topic. However, a significant amount of the material falls outside the realm of this assignment. The last chapter though, Landed Forestry, is very pertinent to the question of ethical forestry, and how to practice it.

As stated in my interview post, ethical forestry is about managing for a healthy forest. This means that all components of the forest need to be managed, not just maximum timber species growth and the number of board feet taken out of the woods every year. A lot of problems face the forester trying to manage in an ethical fashion. One of the biggest factors that Keith Thompson, the Chittenden County Forester, brought up, was the fragmentation of a landscape and the limitations of private property.

Because of our very strict cultural views of land owner rights, a landowner can really do anything they want with their land. Landscapes, of course, encompass many properties, large and small. The problem this poses for a forester is that each landowner may want something different, or a large chunk of the land may become a housing development. Animals need to move through this landscape too, and different land owners may own separate properties that each contain vital habitat.

Another problem is foresters changing locations and being shifted around between different ecosystems and landscapes. In the US forest service, foresters are often posted to many different forests over the course of their careers. This means that as soon as a forester is really figuring out the specifics and quirks of his forest, he is relocated to an alien landscape. Furthermore, less and less “dirt-forestry” is being practiced. Foresters are spending less time out in the woods getting a feel for their land, and more and more time using computer simulations and aerial surveys, which often times do not accurately predict the real situation on the ground.

The chapter Landed Forestry: A Vision for the Future discusses a possible solution to this state of affairs. Raphael looks overseas, to the Swiss system of forestry, to try and find answers to some of our current problems. The topic of Swiss forestry is also of particular interest to me, both because I am part Swiss, and because I cut down and bucked my first big tree (a red maple) under the supervision of an ancient former forestry student from Switzerland.

The European nations realized the importance of forestry much earlier than anyone in America did. With many centuries of exploitation, limited land availability, and rising populations to deal with, the Europeans realized quickly that they risked losing their forests entirely if they did not start managing them and regulating cutting. Indeed, the first forest reserves where created in England as early as the Middle Ages, partly to ensure a reliable source of oak for ship building, vital for national defense. By the 18th century, increased agricultural clearing, naval production and industrialization meant that forests were being pushed to their breaking point. Around the same time, the scientific method had been developed. Because of these two developments, the science of forestry was born in Germany.

In the US, the ideas of scientific based management, regulated cutting and conservation took many years to be adopted. The first German foresters started practicing in the early 1700s, while scientific forestry did not really take off in the US until Gifford Pinchot introduced it in the early 20th century, after he visited Germany. Of course, in the US during the 1700s people would have called you crazy if you said that there was going to be land and timber shortages in the future. The Europeans have had to deal with these problems for centuries, felt the effects of poor forest management for centuries, and had centuries to try out different management strategies. By contrast, in our own country we have only practiced scientific forestry for 100 years, and had to repeat a lot of the trial and error of the German foresters of 200 years ago.

Indeed, the German foresters have had generations to study their research forests, and record differences in growth. The Germans began their first experiments with plantation growing even-aged monocultures of spruce in the 1750s. This first growth generated a huge yield. Each successive generation of monoculture, however, grew slower and slower, suffered terribly from disease, and eventually failed, no matter what the Germans tried. By the 1940s, plantation growing was abandoned. In the states, ironically, we started utilizing even-aged monoculture plantations in the 1940s.

The real topic I want to delve into is what landed forestry actually is, and why we could take a lesson from the Swiss. As I mentioned before, Europeans have had to deal with the conflict between fast growing numbers of humans and limited amounts of forests and land for centuries. Additionally, due to the Alps, the Swiss have long known about the ecosystem services that forests provide. In Switzerland, avalanches down these steep mountain slopes have always been a serious problem. By allowing the forest to remain on the hillsides, the Swiss were able to lower the damage of these events. For many years and to this day, all land under forest cover must remain forested into perpetuity.

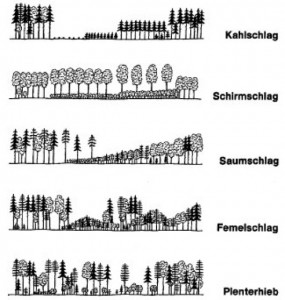

Swiss farmers have been practicing what we would now call selective cutting for centuries, without a scientific basis, but in tune with the natural environment. In the early 20th century, the Swiss began to put scientific principles behind their traditions, and started what we now call uneven aged management. There are many unique features of the Swiss system

Rather than managing woodlots and forests that have been created with political and economic boundaries, as we do here, the Swiss manage their forests by watershed, with a long-time, resident forester. In Switzerland, forests are not privately owned, but in the public domain. Despite this, locals have a deep connection to their land. Instead of foresters being trained in one place, and then sent to manage random forests across the country, “[t]hey go off to the university, and then they come back to their homes. They work right along with their fathers. A tradition develops of working on the same land for generation after generation. There is more interest in keeping the land productive” (Raphael, 226). One of the most important aspects of this system is that the forester actually lives in the forest, and fells trees with the logger. The forester is buried in the forest when he dies. The chief forester of the region is also an elected official, which means that there has to be good working relationships between the public and the foresters.

The uneven aged management system utilized, also called “garden forestry”, is based on the principles of sustained and sustainable yield. Much less wood is taken out of the forest per harvest, but it comes out regularly, contributing money regularly. By selectively cutting, trees can be selected both to take advantage of the current timber market and to improve the forest. If there is a good market for high quality wood one year, some high quality, mature trees could be taken. If the next year the mills are paying more for lower quality trees, then those could be harvested instead, improving the genetics of the forest. Essentially, what the Swiss have is a system that is

“…personalized. The foresters and forest workers are dealing with individual trees on limited forest land, not with large, anonymous tracts of raw timber. There is no financial reward for liquidating resources; indeed, the professional standards are based on how well regeneration can be accomplished. The forest is seen as a complete entity that grows timber, nourishes wildlife, stabilizes hillsides, provides water, and serves the recreational needs of human beings. The forester is the caretaker-but not the owner-of this entity. He is a “ranger” in the old-fashioned sense: the keeper of the woods…The Swiss system…evolved from a combination of local tradition and a deeply felt need. The need was to maximize sustained-yield production on a small amount of land, to manage the land to its optimum potential, to waste nothing. The tradition was the famers’ bonding to the land over successive generations, and also their respect for the inherent value of trees” (Raphael, 227).

There are many similarities between Vermont and Switzerland. We both have a mountainous and hilly landscape, along with a pasture based agricultural tradition and a relatively small amount of land compared to other timber states. Uneven aged management is the main silvicultural system practiced here and money is not chief motivator for harvests. What I think we could really apply from the Swiss system is a more integrated landscape management approach.

Of course, private property is sacrosanct in our culture, and forests in Vermont are mainly under private ownership. It would be politically impossible, and I think unnecessary and morally suspect, to turnover our privately held lands to the state for management. However, what I do think would do a considerable deal of good is a landowner cooperative.

Landowners in a region could opt in to this cooperative, which could then be managed as a whole block, while still respecting property rights. The advantages of such a system would be multiple, the main two being more effective management for both timber and wildlife, and a more efficient economy of scale. The animals that people most identify with, want to see more of, and want to hunt, are the large animals; the black bear, the white-tailed deer, and the moose. Because these animals are large, they have large ranges. By managing all the woodlots in the forest as a whole, we can take into account these large ranges. We would be able to plot and manage different kinds of habitats across the whole landscape more effectively.By managing on a larger scale, timber harvests could be both more profitable and more efficient. When harvesting timber, the operating costs are the same everyday, plus the cost of setting up the job. Currently, if two landholders wanted to run a timber sale, they would each have to hire a forester, which is expensive. Then the logger has to bring his machinery to the site, set up a landing, clear trails. The cost of running the machinery each day of work is also expensive. With the larger block system, these costs could be minimized, but the same amount of wood could be extracted. Access trails could be minimized across the entire landscape, but be concentrated and laid for maximum efficiency. Furthermore, easements could be placed on the landscape as a whole, conserving large blocks of forest from development. Landowners who were part of this system could receive a lot of education, and would be personally involved in a major conservation effort.

I think that such a system could be very possible in Vermont. In order to preserve our fragmenting landscape and prevent a suburbanization of the woods, landowner outreach is more important than ever. If we want to keep our forests as forests, I think we need to establish a system like the Swiss, with families tied to their landscape and with a vested interest in improving and maintaining them.

Citation:

Raphael, R. (1981). Tree Talk: The People and Politics of Timber (2nd ed.) (M. Livingston,

Illustrator). Washington, DC: Island Press.