Ethical Forestry in Vermont Interview:

Keith Thompson, Chittenden County Forester

By Harry Voelkel

I interviewed the county forester of Chittenden County to gain a better insight into what sustainable and ethical forestry looks like on the ground here in Vermont. As a state forester, Keith Thompson is uniquely suited to talk about ethical concerns.

|

| A Forester. Source: http://www.irmforestry.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/IMG_20130505_154715.jpg |

To those not acquainted with forestry terminology, the term “forester” can be a little confusing, and there are several different types of forester. Foresters can have very different roles depending on what part of the industry they are involved with. Generally, foresters are usually responsible for managing woodlands. This is done by inventorying and assessing that forest, and implementing a prescription depending on the objectives for that piece of land. Foresters can work for private companies, different agencies, and be hired by small landowners. Worth noting is that foresters play a different role than loggers. Loggers wield the chainsaw, operate machinery, and build roads. The forester would lay out the road and mark the trees to be cut, according to his management plan. The role of a county forester, employed by the state, rather than a private entity, is quite unique.

The county forester does not create management plans for landowners, instead his role is a little different. His job is to monitor the condition of forestry in his county. As a paid state employee he gives free consultations and advice to forest landowners along with providing education and resources. One of his most important tasks is to review all the management plans for woodlots in the county, and to make sure that they are being adhered to, as well as making sure that water quality and harvesting guide lines are being adhered to. Essentially, his role is making sure that ethical forestry is being practiced in Chittenden County. Chittenden County is also a unique place in the Vermont forestry scene. While it is the most urban county in the state, with the highest population, it also has some of the state’s largest tracts of unbroken woodland and important habitat, such as the forests around Bolton and Camel’s Hump. Management here must be on a town by town basis.

|

| Source:http://fhsarchives.wordpress.com/tag/us-forest-service/ |

My first question was “how would you define ethical forestry?” His answer was that the bottom line was to maintain a healthy forest. However, what constitutes a healthy forest means totally different things for different people. For him, the clue is in the name “forester”. The role of the forester is to manage the whole forest, not just the trees. Regard this concept, he believed that Aldo Leopold said it best with his famous line:

“The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant, “What good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

This way of thinking, while relatively mainstream today, is not universally accepted across the forestry business. Instead, there are different shades of ethical forestry. In industrial forests, the priority of the forest is to produce fast growing trees and cheap timber. These forests, if you can call them that, are plantations of even-aged trees clear-cut on short rotations and treated heavily with pesticides. This leaves little room for ethics. On less intensively managed forests, there is room for ethics, even if timber is still the priority. An example of this is the forester’s for the birds’ project, which gives guidelines for harvesting that also help create habitat for different bird species. Water quality guidelines also make sure that soil is conserved, which is only possible when the forest is managed to a certain standard.

|

| Source:http://fhsarchives.wordpress.com/tag/us-forest-service/ |

In Vermont, the majority of forests are privately owned and quite small. This has several different impacts on the practice of ethical forestry in the state. The first is that a landowner who doesn’t prioritize harvesting is not punished financially. On such a small scale, the cost of harvesting the timber is barely covered by the value of the logs. Cutting these forests harder is not worth the couple hundred extra bucks the landowner might make.

A further effect of small properties and small harvests is that the supply cannot meet the demand for wood. Keith highlighted two valuable trees which are in high demand, but have limited supply under this system. These are sugar maple and northern red oak. Most of the sugar maple in the state is kept under maple sugar production, and there is simply not enough red oak growing in Vermont. The state’s timber needs for these trees are not being met locally. The northern hardwoods that grow here are valuable for high quality forest products such as furniture, or burn well as firewood, but softwoods are what fill the construction materials role. Eastern white pine is one of our most valuable native woods for construction, but likewise is not in found in great enough quantities. Plantation grown yellow pines or tulip poplar in the south or Douglas fir in the west fill this role and are much cheaper.

“Why cut at all then? You may ask, if there is little financial benefit to the landowner. His response was that the harvesting and management was about more than the value of the wood itself.

|

| Source: http://www.history.com/images/media/video/history_ax_men_01_how_to_fell_a_tree _sf_1155318 /History_Ax_Men_01_How_To_Fell_A_Tree_SF_still_624x352.jpg |

Most harvesting is done to keep the land in the “Use Value Appraisal” current use program or UVA for short. This program is an important part of keeping forest land forested in Vermont. This program allows undeveloped land, either forest or agricultural, to be taxed on its produce, rather than on its real estate value. This gives a landowners a financial incentive not to turn to property development, and keeps rural land more affordable.

Harvesting also has an important cultural and social role in Vermont. Many forest landowners are not native to the countryside, and do not have the same relationship to the forest that previous generations had. Formerly, local forest products played a major role in almost everybody’s life, and people had a direct connection with their land. Even if today we see their cutting as overly aggressive or poorly planned, they still relied on their land in a way that we don’t. This made them value their land.

Keith’s opinion is that if we don’t utilize the forest, we aren’t aware of the potential of the land, and we won’t value it. Whether these landowners do or do not harvest their own forests, they still buy wood. If one just buys wood cut from somewhere else, it has no bearing on the consumer. They don’t appreciate it. Wood has to come from cutting down trees somewhere. If you harvest your own land, then you gain an appreciation for where the wood comes from and the knowledge that it comes from a responsibly managed forest and an ethically conducted harvest. If a landowner does not value their forest as forest, then they might value it for home sites instead.

|

| Source: http://www.fountainforestry.com/images/timber-sale1.jpg |

“Benign neglect” of a forest may sound like an environmentally friendly approach to managing a forest. In the 21st century, it can reduce the capacity for that forest to regenerate itself. While the virgin forests of pre-colonial times were certainly able to keep themselves healthy, the modern forest faces more complex issues. Centuries of poor management and hard cutting, along with the introduction of invasive species and disease, means that our forests are more vulnerable than they have ever been. In an unmanaged forest, invasive species may run rampant, outcompeting regeneration of native plants and degrading wildlife habitat.

Through his services, Keith is able to educate landowners and redress these kind of issues. One of the most important ways to do this is a walk with the landowner on their property. Every forest owner wants to see their land as unique and special. Luckily for them, every forest is unique. By pointing out this uniqueness and telling the landowner a narrative about their land, the forester is able to connect the owner to the land. He can advise the landowner on what the land needs, what kinds of logging job could be used, and give them a contact list of good consulting foresters who could draft a management plan.

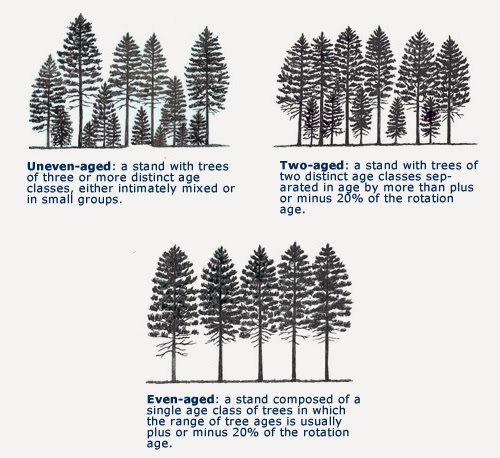

My next question was how can forestry techniques to help the forest? The ethical harvesting of a forest depends on several factors and is very site dependent. When a healthy forest is encountered, the key objective is to not mess it up. Otherwise, the goal is to create diversity and complexity. In many cases, such as that of a young forest or fields returning to forest, there is probably a lack of these. Harvesting can be used to create standing dead trees or “snags”, along with logs and piles of woody debris on the forest floor, important for bird habitat. One of the most important goals of a harvest is to create multiple age classes of trees in a forest, what is called uneven aged management. This is in stark contrast to industrial forests, which are composed of uniform rows of one tree species of all the same age.

|

| Management Types. Source: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/fmg/nfmg/img/silv/standtypes.jpg |

|

| Source: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-hUzHk1kmotI/UQAIC639ASI/ AAAAAAAAW04/XZGYX2dofkg/s1600/audubonlogging.jpg |

Uneven aged management means the creation of healthy canopy trees, mid-story trees, and a wealth of saplings in the understory. This mimics the form forests take naturally, but takes many, many years to develop in the wild. This broad range of tree heights and ages makes the forest more resilient to disturbance events. Keith gave two examples of this. The first was a large ice storm several years ago. This storm bent over and snapped most of the young trees in the forest. However, the large trees stayed intact, ensuring a seed source for the next wave of growth, so the forest could regenerate itself. In 2010, there was a powerful windstorm event. This storm felled many of the tallest trees in the Hinesburg town forest. But there were many understory and mid-story trees able to grow and take the larger trees’ place in the canopy. Maintaining a diversity of species also helps to keep the forest resistant to disease, which can wipe out monocultures.

However, there are some trade-offs with harvesting. Soil compaction, erosion, and damage to living trees can all be caused by harvesting. Most forestry today involves the usage of heavy equipment, usually to remove the wood from the forest. This heavy machinery saves a lot of time and human effort, but is not without adverse effects. Healthy soil needs a certain amount of space between particles for air. Heavy machinery can compact the soil, leaving roots unable to make use of it. This especially a problem in the heavy clay soils found in Charlotte and Hinesburg. This heavy machinery can also damage the roots themselves. The building of roads in forests can mitigate this problem, by limiting the areas where heavy machinery travels. Felling trees and skidding logs out of the forest can cause damage to other living trees, sometimes killing them.

|

| Modern Horse Logging. Souce: http://blog.mlive.com/bctimes/2008/02/large_2008022-01-horse-logging-fraser.jpg |

I was curious if the use of more horse logging, the method of logging where horses drag the wood out, instead of cables or machines, could limit soil and tree damage. I was also interested how much horse logging goes on in Chittenden County. My answer was that horse logging does have some potential, but also has some major drawbacks. The biggest one is that it takes a lot of time and effort to drag a log out by horse. In modern horse logging, only one or a pair of horses are used, and they can only pull out one log at a time. When an operation barely makes a profit with time efficient techniques, it would be difficult for a very time consuming method to make any money at all. On the flip side, a horse logging operation has very little in overhead costs, compared to the thousands of dollars needed for the heavy machinery. In Chittenden County, there is only a little bit of this kind of logging going on. As far as Keith knows, there are only two loggers using animals.

Finally, I wanted to know what ethical dilemmas Keith himself is dealing with, and what concerns he has about the forestry industry in Vermont. The biggest one for him was the issue of invasive species and how best to deal with them. Killing these plants is very expensive, as well as time consuming. Large amounts of herbicides would have to be used. He fears that the result of not managing the problem could be the loss of our forests. He thinks we need to study what the long term expansion and effects of invasives will look like, and research more effective techniques for stopping them. One method he thinks might be effective is using the environmental controls to fight invasives, like reducing the deer browse of native species, which gives invasives a competitive advantage. More public awareness of the forest economy is one thing he thinks is essential for the vitality of the state. With forest products loosing profitability, mills have been closing down all over the state. Another issue is that the majority of the landowners are getting quite old. When they die, what will happen to their forests? They may be divided between children, resulting in more fragmentation. The spread of many forest diseases are another great threat, such as emerald ash borer, or hemlock woolly adelgid.

Everything consider, Vermont faces a unique set of challenges. On one hand there is little motivation to over harvest our forests or engage in destructive forms of logging. On the flip side, a whole new range of challenges face us. A loss of connection with the forest and the landscape means that many do not value their resources as much as previous generations did. Forest tracts are at great risk of becoming housing subdivision. Invasive species threaten to out compete our native plants. Through the ethical practice of forestry, hopefully we can have a toolkit to combat these problems.

|

| Source:http://fhsarchives.wordpress.com/tag/us-forest-service/ |