Written by Jen Garrett-Ostermiller

Introduction to the Series: “A Case for Teaching the Hidden Curriculum”

This is an introductory post where we explore the academic challenges college students face, created and exacerbated by Covid, and kicks off a series titled “A Case for Teaching the Hidden Curriculum.” Upcoming posts in this series will highlight curriculum-based academic skill development as a partial antidote to these challenges.

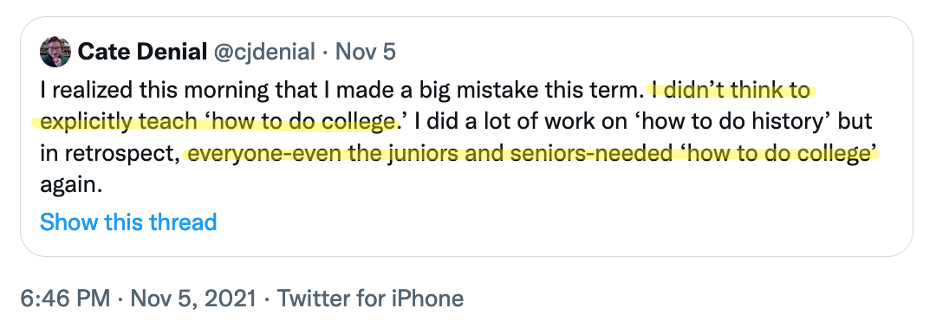

Earlier this month, Dr. Cate Denial, author of the forthcoming book A Pedagogy of Kindness wrote on twitter, “I realized this morning that I made a big mistake this term. I didn’t think to explicitly teach ‘how to do college.’ I did a lot of work on ‘how to do history,’ but in retrospect, everyone-even the juniors and seniors-needed ‘how to do college’ again.” (emphasis added)

This concept of students struggling to “do college” is echoed in sentiments being felt right here at UVM this semester. It makes sense. Since that day in March 2020 when everything suddenly went remote, learners and educators alike have been adapting to new ways of doing school. Despite attempts to define this fall as some version of normal, we are all still in the midst of a global pandemic, and many of us are depleted.

Impacts of the Covid pandemic on college students

Washington Post staff writers documented challenges directly connected to the stress of living and learning in a global pandemic:

The Center for Collegiate Mental Health at Pennsylvania State University reviewed data on 43,000 college students who sought treatment in fall 2020 at 137 counseling centers. Of them, 72 percent reported that the pandemic had negatively affected their mental health. Sixty-eight percent said it had hurt their motivation or focus, and 67 percent said it led to feelings of loneliness or isolation.

This leads us to ask, how are students supposed to know how to manage time and projects when attention spans are shortened and motivation is lowered? How are students supposed to know how to effectively read and study while also navigating the emotional and mental stresses of a collective (and often personal) traumatic experience?

Additionally, after 18 months of learning how to “do emergency remote learning,” students may be experiencing cognitive whiplash as they are asked to prepare for and engage in primarily in-person classes with a range of norms and expectations. Practical questions emerge. How do students know how to participate in class when they have spent the better part of two years engaging meaningfully in a written chat? How do they know how to navigate group projects? How do they know how to take notes in a large in-person lecture?

Academic skill development in college

Now, more than ever, students need help to learn how to “do college.” Sometimes called the hidden curriculum of college, academic skill development—time management, studying skills, reading strategies, and communication approaches—is essential for success. Some students come to college with these skills, but most gain them through trial and error, emulating peers, or (in the most fortuitous circumstances) with the coaching of an advisor or mentor.

Acquisition of these academic skills has a positive effect on retention. If all students are taught to become more adept with these skills as early as possible, we should see more equitable outcomes. Additionally, supporting students to develop academic skills in the classroom is a proactive intervention. When all students are more equipped to “do college,” panicked emails about missed deadlines or requests for extra credit at the end of the semester are reduced.

An argument can be made that attention to academic skills belongs in the curriculum whether or not we’re in a pandemic. A college degree signals skill development beyond disciplinary aptitude. Earning a diploma indicates that graduates have demonstrated effective time and project management, can independently learn new and often complex information, can manage stressful circumstances, know how to communicate with a range of constituents, and can use information literacy skills for inquiry-based research. If we expect these skills to be an outcome of a college education, then teaching these skills becomes integral.

What do we know about teaching the hidden curriculum?

In a large study with over 10,000 undergraduates, Bowman, Miller, Woosley, Maxwell, & Kolze (2018) identify that hands-on, real-world application is more effective than simply telling students about the best strategies for approaching school.

For example, a time management workshop should have students engage with their own schedules and share how they could approach or structure these differently (in ways that are consistent with the intended learning outcomes), as opposed to simply providing a list of time management tips that students may or may not use. (p. 149)

The classroom is therefore an ideal space for students to learn about and practice these academic skills.

In this series, we are not advocating that every instructor incorporate teaching every aspect of the hidden curriculum in every class they teach. That would be overwhelming for instructors and students alike. However, we do think that identifying one or two key skills particularly relevant for your class will have an impact.

Upcoming series on supporting students’ academic success

Over the coming months, CTL staff and faculty associates and the Center for Academic Success will publish a series of blog posts and host workshops about practical ways you can support students in developing behavioral and affective skills that will support their academic success, making the hidden curriculum both visible and valued.

We’ll be sharing posts about how to support students’ development of the following on life skills (e.g., time management strategies, growth mindset), classroom skills (e.g., test taking, participating in discussion), and learning skills (e.g., reading strategies, spaced retrieval).

If you have an idea you’d like to share about how you build academic skill development into your teaching, please write to ctl@uvm.edu, and we’ll include it in a future post.

References

Bowman, N., Miller, A., Woosley, S., Maxwell, N., & Kolze, M. (2018). Understanding the link between noncognitive attributes and college retention. Research in Higher Education, 60(2), 135-152.

Svrluga, S. & Anderson, N. (2021, October 14). College students struggle with mental health as pandemic drags on. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/10/14/college-suicide-mental-health-unc/