Home | Introduction | Literature Review | Data & Analysis | Conclusion | Sources

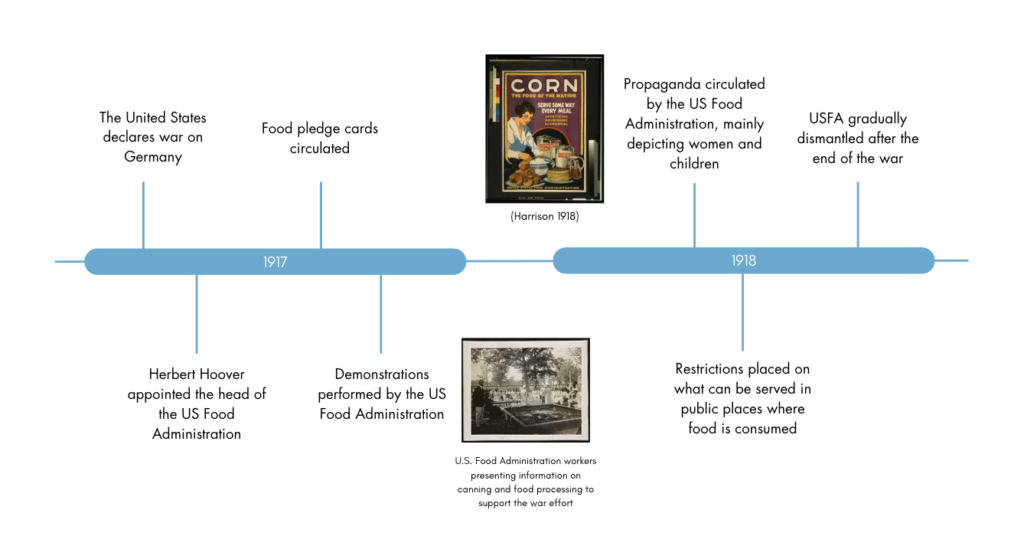

The primary documents and data from 1917-1918 provide evidence of the means by which the campaign exerted its influence and its effects upon women and children. As an overview, this timeline demonstrates the key events during the span of the US Food Administration.

The Ideal Family and Housewife

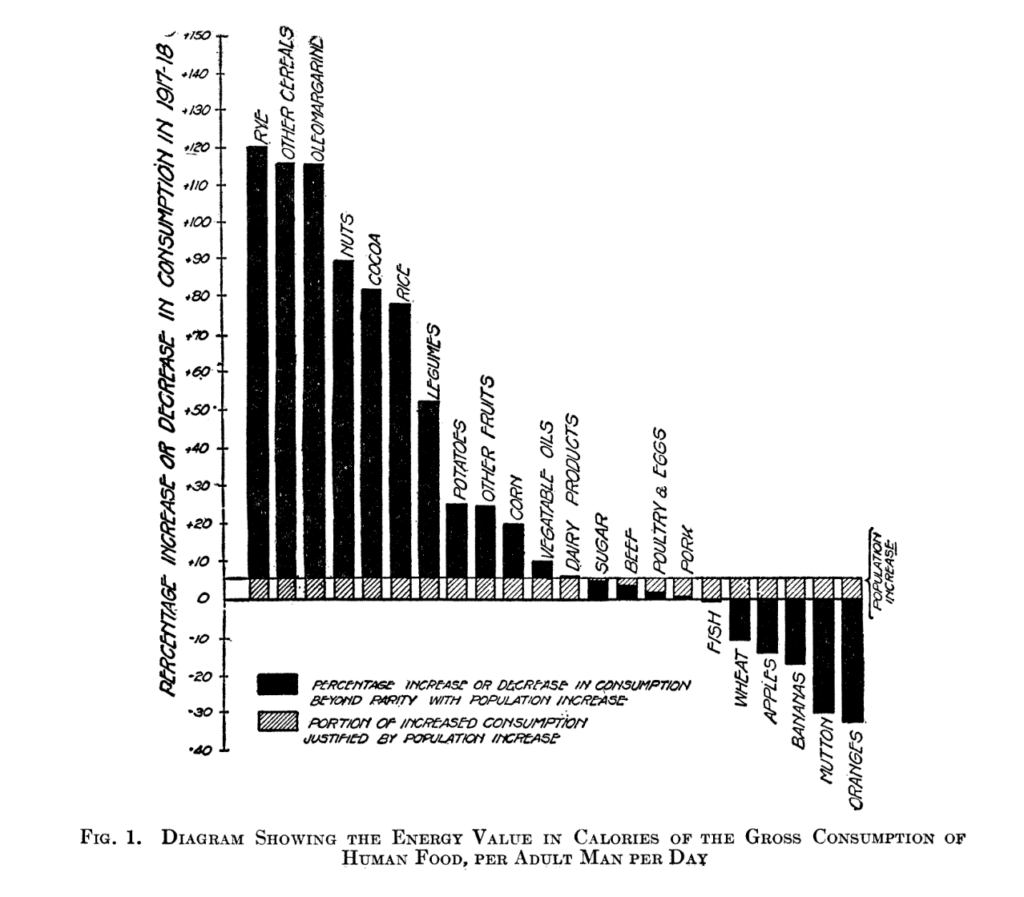

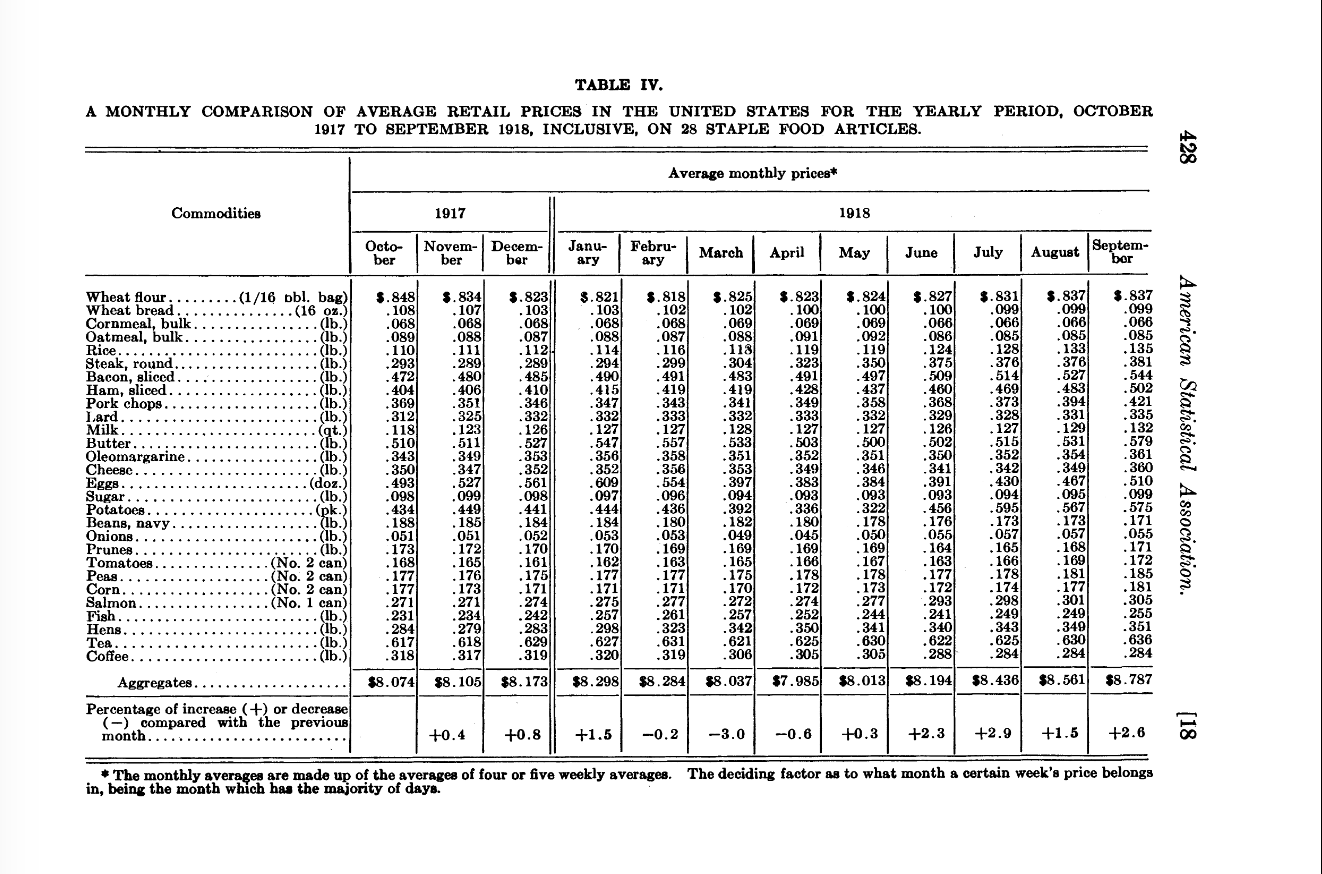

The food conservation campaign impressed upon women their integral role in the war effort while keeping them trapped in the kitchen. Ida Clark’s book American Women and the World War was written in 1918 in order to convince women, and society as a whole, of the important role women had in the war effort. She introduces the book by underscoring women’s “…tremendous opportunities and responsibilities in the present world conflict…” (Clark 1918) As argued by Dumenil (2017), Clark uses the idea that women can serve their patriotic duties from their kitchens by using phrases such as the “Army of American Housewives,” “make of the housewife’s apron a uniform of national significance,” that “Every American housewife was expected to take her place in the ranks of those serving the country” (Clark 1918). In order to aid women in the preparation of new dishes which used substituted ingredients, many guides were published in the form of pamphlets or articles in women’s magazines. The Journal of Home Economics would have been a publication primarily read by women in charge of their homes. A section of the 1918 edition titled “For the Homemaker: Vegetable Oils and Their Use in Cooking” argues for the substitution of shortening for animal fats such as butter. In this section, they aim to convince women across the US to reduce their use of animal fats using arguments such as “Miss Elizabeth W. Miller of Our Department has had delicious pie crusts made with cottonseed or corn oils” (Blunt 1918). Another section of the 1918 Journal of Home economics addresses new food cards distributed by the United States Food Administration. These cards instruct, presumably women, to adhere to “one wheatless day,” “one meatless day,” and to “materially reduce sugar” (Journal of Home Economics 1918) The results of these guides are demonstrated in the chart below from an article by the American Statistical Association’s article “Food Thrift.”

The chart shows that while the consumption of Wheat decreased, it was replaced by an increased consumption of Rye, other Cereals, and Oleomargarine.

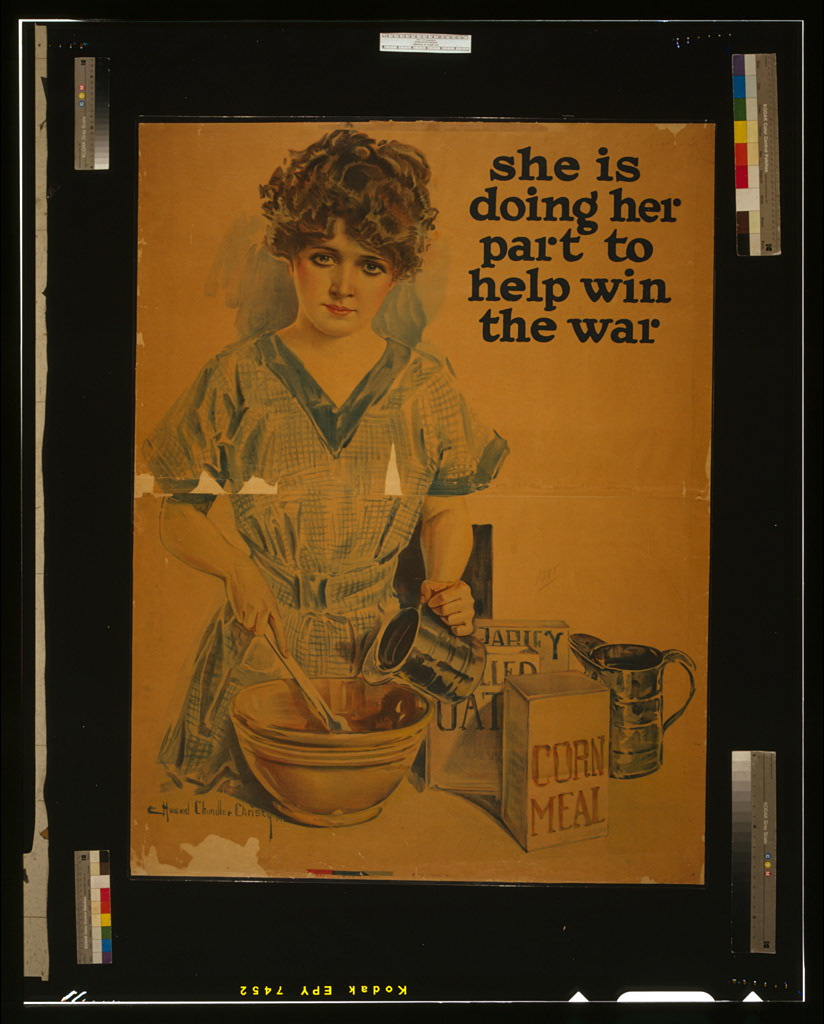

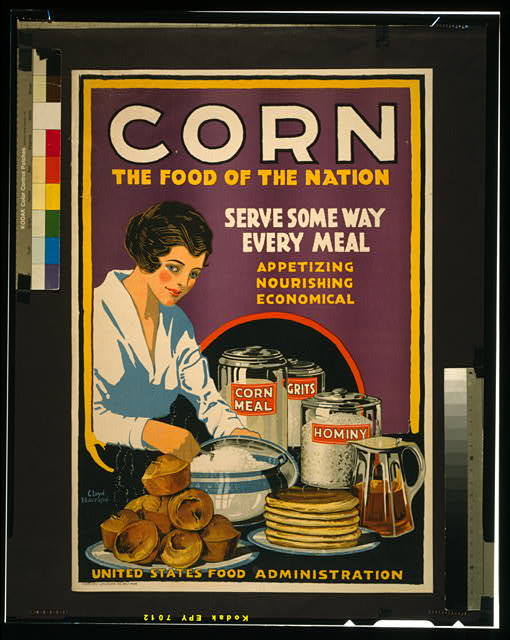

These shifts in peoples’ eating habits would not have been possible without a substantial propaganda campaign. As explained by Tunc (2012), food conservation propaganda appealed to the stereotype of the housewife because they were an integral part of food production and consumption. Many posters depict women using food preparation as a means to serve their patriotic duty.

She is doing her part to help win the war / Howard Chandler Christy 1918.

Apart from substituting different food items, only eating enough to sustain oneself was a message which purveyed the food conservation movement. According to a section of the Journal of Home Economics, the USFA claimed that “…he or she should only eat that which is necessary to maintain bodily health and strength and unselfishly select those foodstuffs…” (Journal of Home Economics 1918) And, “Every man, woman and child should be properly nourished. Undernourished people cannot attain the highest pitch of efficiency. The same is true of overnourished people” (The National Magazine Boston 1917). The difficulty in achieving meals which would efficiently provide enough nutrients to sustain oneself is also outlined in Charlotte Perkin’s The Housekeeper and the Food Problem. One of the problems with preparing food was “how to prepare and serve it, with the least cost in time, labor and money, and with the best effect on our health and happiness” (Perkin 1917) While being cheap and nutritious, food also had to convey a more emotional meaning. This solidifies the argument made by Parkin in her book “Food is Love”: that through their roles as the housewife and a preparer of food, women should demonstrate their love and nurture their families. However, during this time, food not only had to represent love, but also patriotism and support for a national effort.

Another changing aspect of a woman’s role was becoming the manager of the family budget. Keeping the prices of food to a reasonable level was also a focus of the US Food Administration. These prices would have mostly influenced the women who were in charge of preparing and buying foods for their families. The results of these efforts are demonstrated in the table below. The most popular food commodities are listed, along with how their retail prices changed from October 1917 to September 1918. During that period, food prices remained mostly stable.

(Pearl & Burger, 1919, pg. 428)

Women being involved with the family economy and budgeting is another aspect of the new modern family in which men and women’s roles overlapped, as discussed by Macleod (1998). Many pamphlets were dedicated to instructing women on how to feed their families cheaply. This includes “How to Save Money on Food: Home Canning, Preserving without Sugar, Drying Fruits, Salt Packing, Food Values, as Recommended by the United States Government” which claims “How to save money is a subject dear to a woman’s heart” and describes different methods of preserving foods (The National Magazine Boston, 1917). Through the canning movement, the production of canned goods was brought back into the home. This exemplifies the arguments made by Valentine (2001) and Macleod (1998) that the home was at once a place sheltered from what was traditionally viewed as work, but also a place of unpaid labor.

The Role of Children

Gross (2013) argued that in the war, children were forced to take on a more “adult” role. This is exemplified in the US Department of Agriculture’s report on the “Accomplishments of Boys and Girls’ Clubs in Food Conservation and Preservation” in which he exalts the role that children have played in the food conservation effort through Boys’ and Girls’ clubs.

“Boys and girls have always played a serious and important part in the great problems of war and peace. The present crisis will furnish to our junior citizens great opportunities for manly and womanly service of all kinds. President Wilson has called them as definitely into his army as he has the men who wear the official naval and military uniforms. Uncle Sam’s food army now numbers over two million boys and girls who have enlisted for full patriotic service during the war and who have added to their oath of allegiance to the flag the following consecration pledge: ‘I consecrate my head, heart, hands and health, through food production and food conservation, to help win the world war and world peace.’”

(Benson, 1917, pg. 147)

The pledge equates winning the war with the efforts of each individual to conserve food. In doing so, Benson brings a larger global conflict to an individual level. This also places more pressure upon the children, and they are not sheltered from global events.

The prominent role for children during this period was also based on the view that children are hope for the future and a pride of national identity. President Wilson said to children visiting the White House that : “…you of the farm and the home constitute the nobility of our nation” (Benson 1917) As such, the nutrition and health of children was viewed as integral. In Lucy Gillett’s Food Primer for the Home, she outlines general guidelines for how mothers should feed their children. She begins with the statement: “Health is a National Obligation. Good Food Habits are Necessary for Health.” In doing so, she makes mothers’ individual choices about how to feed their children a part of a larger national cause. According to Gillett, “good food habits” include “the eating of the right kinds of food, the eating of the right amount of food, the eating of this food at the right time and in the proper manner. ” She argues that children should be taught these habits when they are young because it is when they are the most impressionable. This idea sits at the foundation of why the food conservation campaign targeted children– because their belief systems haven’t been as solidified as adults’.

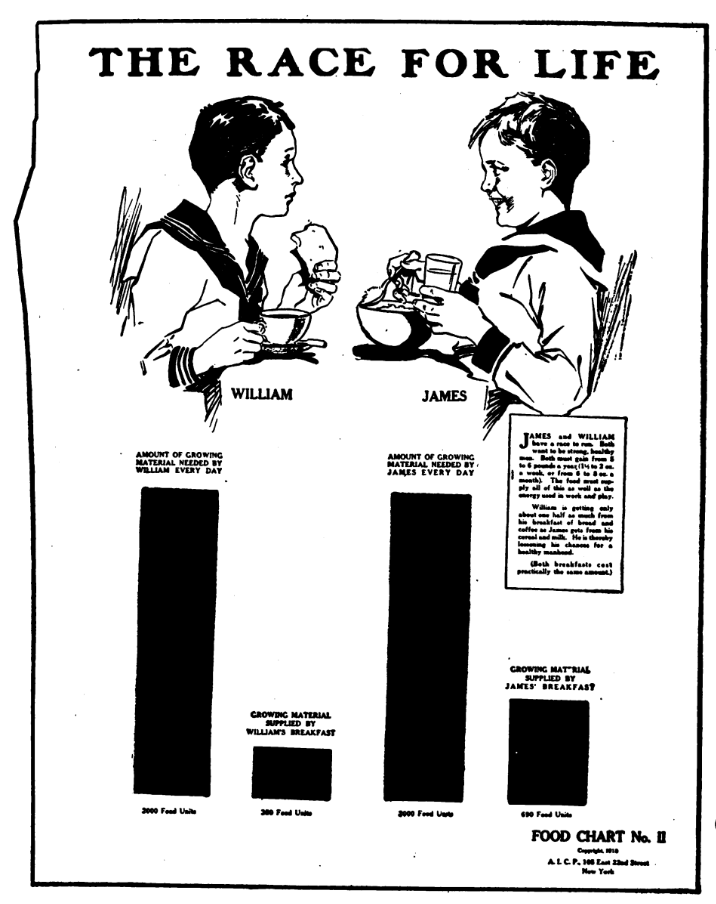

This chart included in Gillett’s Food Primer posits food as the main reason one child will succeed in life, while another will fall behind. This places a greater burden on childhood, as it is the foundation of adulthood.

(Gillett, 1918, pg. 5)

During this time period, birth rates fell and the ratio of children to adults decreased. As such, there were more resources to spend per child and each child became more precious (Macleod 1998). This trend is visualized in the maps, which represent the percent of the population that was 18 and younger in 1910 and 1920. The ability to have a greater amount of resources per child may have also been the reason that the government focused their propaganda towards children. And, it may have allowed parents to focus greater efforts towards providing the best nutrition for each child through their food choices.

(Social Explorer, 2024)