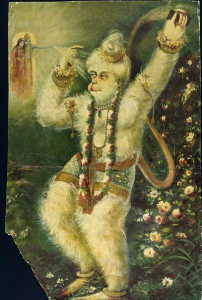

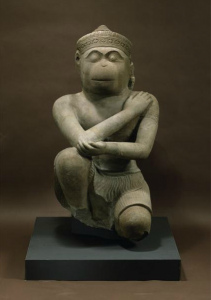

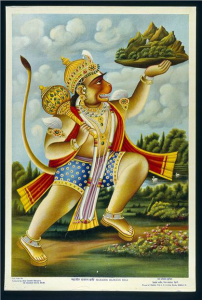

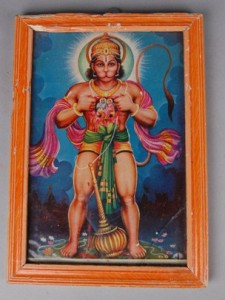

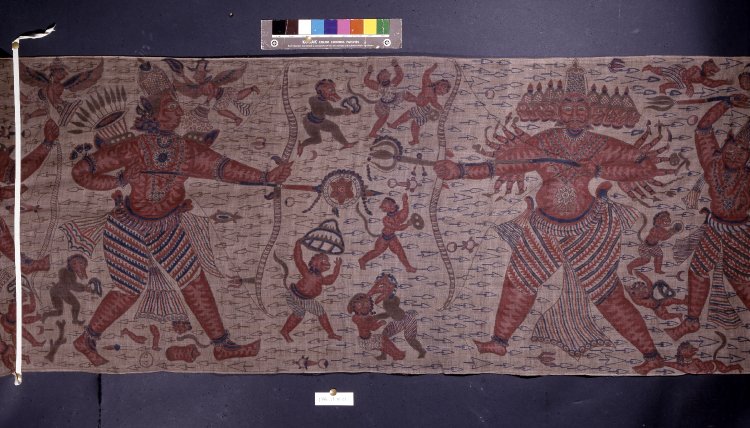

In modern media Hanuman, the beloved half-monkey god, stars in popular comic books, saturday morning cartoons, and feature films targeted toward children ages 3-8. He is a rebellious, tounge in cheeck,“bad guy fighting” superhero that all children want to be like. He is an icon and role model for boys young and old. However in traditional tellings of the Ramayana, Hanuman is presented as a devotee of Rama, the original star of the epic. Are these two contrasted characteristics given to Hanuman to attract young boys to the positive characteristic of the role model and story of the Ramayana, or are the positive characteristics lost in the crime fighting action?

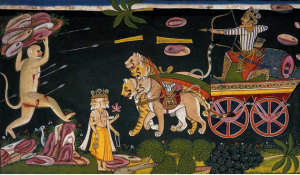

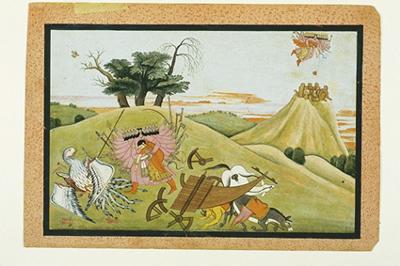

Hanuman is featured and praised in Buck’s Ramayana as a devotee and hero for saving Ram through several brave acts. In Buck’s Ramayana, Hanuman is characterized as calm, collected, brave, strong, all knowing, modest, and a problem solver. Because of his actions, Hanuman joins the “good guy” side of the epic battles along with Ram, Lakshmana, and Sita. However, Hanuman’s characteristics contrast boldly from the other “good guys” of the story. Ram is presented as flaky, unreasonable, selfish, focussed on his strength, and often makes rash decisions. Lakshmana is a dedicated brother who follows Rama’s every command and rarely disagrees. On the contrary, Hanuman boldly shows his disagreement with Ram’s character and is never presented as acting for himself.

Wolcott’s article “Hanuman: The Power-Dispensive Monkey in North Indian Folk Religion” discusses the importance that Hanuman has on popular traditons and that he is the most celebrated/significant character of the Ramayana. Many see Hanuman as a doorway to God because he helps Ram/God in ways that he couldn’t do himself. For example, Hanuman is the only one who is able to find Sita and Ram then becomes dependent on him to complete his mission. There are a lot of side stories that go along with the Ramayana and the most popular feature Hanuman. Wolcott notes that there are also more temples and shrines dedicated Hanuman than for Ram or Sita. Wolcott argues that this is because Hanuman is more relatable and seen as more of an everyday hero.

In order to understand how Hanuman is understood by modern children, I took a look at media commonly consumed by children in India. Comic books, morning cartoons, and big screen movies are largely consumed by young children as they are highly accessible and quite entertaining. As anyone can remember from their own childhood, the movies and TV shows we watch as children are remembered and idolized through adulthood. This media is and highly imfluencial on children’s behavior and interests.

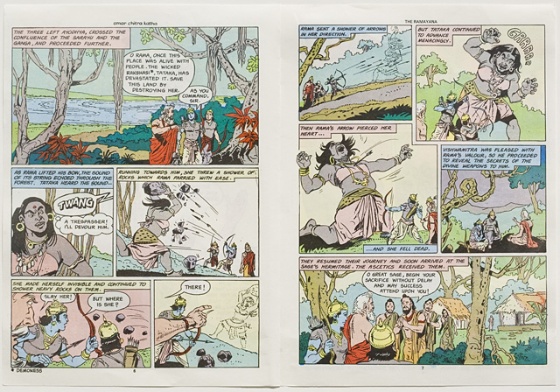

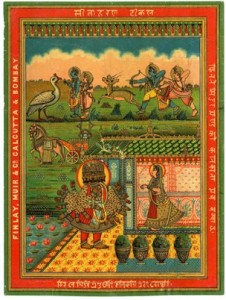

Amar Chitra Katha’s comic book version of the Ramayana is widely distributed and is presented in an accessible and exciting way to children. This version of the Ramayana is

“Then Hanuman assumed a huge form… and leaped into the sky!”

fast-paced and focused on the battlesand adventures between Ram, Ravana, and Hanuman. Hanuman is depicted as a large and strong figure who saves the “good guys” from the “bad guys,” a common comic book storyline. This depiction of Hanuman as stronger hero than Ram, puts Hanuman’s importance in the Ramayana on a pedestal over Ram. It shows young boys that if you are brave, strong, and a little cheeky, you may outsmart “evil” and do your role in saving the “good.” This sets the standard that risky, rebellious, sneaky behavior that shows your strength is seen as positive in young boys. In this version his calmness and modesty, two important characteristics to instill in young boys, is little seen.

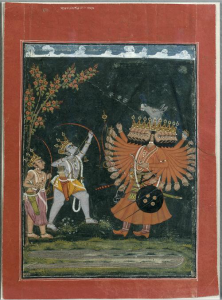

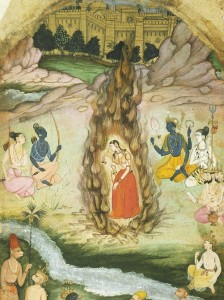

When researching modern images of Hanuman, I came across this ad for a film titled “Hanuman Returns.” The image was alongside an article published by Animation Xpress in 2011 discussing the release of a spin-off television show to the movie.The movie and television show are produced by POGO, a popular channel for children and families. According to their website, POGO is available in India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan and in 5 different languages. The movie and television series is reaching many children, and is pretty obviously targeted at young boys. This image and other modern portrayals of Hanuman are the most useful materials for getting a glimpse of how young boys interpret both Hanuman’s interactions in a religious context and how his behaviors may impact their behaviors.

The ad depicts a reincarnation of Hanuman in the center with several characters from the Ramayana behind him, including Ram. Hanuman is depicted as a young boy, which attracts young boys and sets him as a role model for behavior. He is dressed in modernclothing, but his monkey features, mouth, ears, and tail, are apparent. Hanuman is drawn to be larger than the other characters showing his importance in both the storyline of the movie, but also reflects his role in the Ramayana as young boys will interpret it. Hanuman stands with his arms folded and at a casual pose to be understood as feeling calm about the “bad guys” and gods standing behind him – he is not afraid or nervous to be in their presence, but standing in a position as if he is above the other characters. A lightning bolt and color change divides the ad, categorizing the “good” and the “evil.” The producer summarizes the plot as Hanuman “using his superpowers to vanquish evil and protect the innocent.” It is obvious that the right side of the ad represents the evil and that Ram and Laksmana represent the good. This gives the message to children that some people are always good while others are always bad. As we mentioned in class, the Ramayana itself does not make such a clear distinction.

The Economic Times draws attention to the fact that children, specifically in India, are heavily drawn to animation and animated movies. Using animation, similar to the comic book depiction, makes the stories of the Ramayana more desired, accessible, and relatable to young children.

The article also points to POGO, the home of the Adventures of Hanuman cartoon series, as one of the largest and growing childrens television channels. Since lot of children in India are watching POGO and The New Adventures of Hanuman, his portrayal in this series is very influential on their behavior. The New Adventures of Hanuman depicts the Hanuman boy avatar as the leader of his friend group and problem solving hero. He is fast, strong, brave, takes risks, and acts as a good friend. The children’s television series is fast paced, colorful, full of exciting music, and seems like it would keep any child under the age of nine entertained.

Setting Hanuman as a beloved children’s character makes the story of the Ramayana extremely accessible to anyone and becomes imbedded in pop-culture. As a pop-culture icon, Hanuman becomes the star of the Ramayana. Creators of mass media featuring Hanuman have a lot of power in fostering children’s understanding of religion as they grow older as well as their behavior. In general the produced mass media of Hanuman portrays him as strong, brave, risky, and always willing to help a friend to save the day from the “bad guy.” After consuming media glorifying Hanuman boys’ will most likely perceive the story of the Ramayana in a different light. Instead of seeing it as Ram’s story, they may instead view the series of events as an explanation of Hanuman’s character and more depth of the stories they learned to know and love.