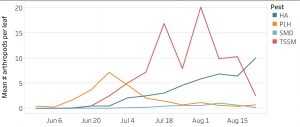

The hop harvest is well underway in the Northeastern U.S., but growers are reporting high aphid populations on hops yet to be harvested. The cool and wet weather we have been experiencing has contributed to an abundance of aphids on a variety of crops including hops.

The hop aphid is one of the most common pest of hops in our region. These soft-bodied plant suckers typically are found on the underside of hop leaves where they feed off the phloem of the plant. While feeding, aphids secrete a substance called “honey dew” that contains excess sugars. If honey dew is secreted in hop cones, the perfect conditions are provided for sooty mold to grow. Plant productivity can be reduced by aphids feeding, but the bigger concern is that aphids can cause direct damage to the cone, and the decreased cone quality and appearance from sooty mold reduces cone marketability.

Please be sure to closely monitor hops that are remaining in the field to decide if they should be harvested early to avoid or minimize damage from aphids.

For more information about hop yard management in general, please visit our website (http://www.uvm.edu/extension/cropsoil/hops), and for more information about the hop aphid and its management, check out the following article: http://www.uvm.edu/extension/cropsoil/wp-content/uploads/Hop-Aphid1.pdf. And remember, keep calm and hop on…

Here is a picture of hop aphids and sooty mold on hop cone (http://www.homebrewtalk.com/showthread.php?t=80510)