Exceptionalism, Pilgrimage, and Romance

Western Exceptionalism

Pilgrimage

Representing Mustang

The “Forbidden Kingdom”

“Where are all of the monks?”

A woman who had clearly been trekking the Annapurna Circuit came up to me one day during lunch time at the Kag Chode, seeing another white woman and wanting to start a conversation. I explained to her that everyone had just eaten lunch (dal bhat with fresh chili paste and bitter melon), and that most of the students took a nap or at least went to their dorm rooms for the hour or so that they had free after eating. The woman was not satisfied by this answer, and she immediately sat down next to me and began asking more questions about what it means to be a monk, why they shave their heads, whether or not the children chose to be there, and on and on.

Although I had been enjoying the quiet of the post-lunch hour, I was happy to try and answer her questions. It gave me a good excuse to call up things I had learned in my classes back in Vermont, and to explain them to another person whose only comparison to Tibetan monks was sadhus in India.

While the conversation frustrated me in the moment, it greatly changed my understanding of tourists coming through Kagbeni, particularly the non-South Asian trekkers on the Annapurna Circuit. I stopped seeing them in terms of what they were providing in economic funds and cultural exchange and began thinking more critically about the impacts of tourism in the town. What frustrated me most about the woman at the gompa in particular was her complaint about paying 200 Nepali rupees – the equivalent of about two dollars – for a night in a hotel in Kagbeni. She argued that this was an extreme price, as the hotels in Manang only charge for food. What she did not account for, however, is that the prices of meals in Manang are raised so that they include the night’s housing when you eat dinner at a hotel. Thus, the packaging appears to be different, but the amount of money spent is similar. Other trekkers I met also complained about the lack of lunch options in Kagbeni, the general lack of spending opportunities there, and the quality of the roads and buses.

According to Ian Reader (2013) these kinds of complaints are common in pilgrimage situations around the world. Reader sums up the interactions with the Circuit trekkers I met aptly: “pilgrims have a long tradition of complaining about the ways they are treated, and even at times [appear] to resent the expenditures on services necessary for their travels” (112). Such complaints may be “embedded in the self-perceptions of pilgrims who are simply not aware that they are central to the whole process of pilgrimage but who also often appear to regard themselves as ‘special’” (113). In the case of the trekkers I met, this self-importance may come from their perception of the separation between trekkers and pilgrims. It also could be related to a feeling of Western exceptionalism, thinking that they deserve different treatment.

This boundary between pilgrims and tourists, however, is increasingly blurred. Today, pilgrimage, tourism, and consumerism are heavily entangled. The physical appearance of pilgrimage routes and sites are shaped to appeal to higher numbers of visitors, and to better represent symbols of cultural heritage rather than exclusively religious locations (Reader 193). As Reader argues, without the marketplace, the tourist shops and hotels and restaurants, pilgrimage sites would lack visitors and would lose their meaning.

In Nepal, tourism generally fits into a few categories. Ken Teague labels these as cultural, ethnic, adventure, and environmental tourism (Teague 1995: 47). I would add to this list the category of “voluntourism” as well, which has arisen especially in the wake of disasters such as the 2015 earthquake outside of Kathmandu. All of these forms of tourism are present in Mustang, in addition to educational tourism of universities, and missionary trips from Australia.

The creation of Nepal as an idealized tourist destination stems from colonial and Orientalist narratives of tourism, which “have strategically functioned to produce geopolitical myths about destinations. The emphasis is on a particular set of illusions that conflate weather and social climate, transforming them into paradise” (d’Hauteserre, 2004: 237). Nepal, for example, is promoted as “the dreamland of ‘Shangri La’” (Teague 1995: 41), highlighting rugged peaks and green forests. This is accentuated further in the discourse around Mustang and its exceptionalism, which relies on statements about the region’s culture, environment, and otherworldly qualities.

In general, there are three types of tourists who come through the Kagbeni. There are the pilgrims going to Muktinath, usually by bus, who come mostly from southern Nepal and parts of India. The summer is a popular time to make this pilgrimage, when people can escape the heat and humidity of the lower elevations. While I was in Kagbeni in June, one guide guessed that about 1000 people visit Muktinath every week during the height of the pilgrimage season in the early summer months. Busloads of these pilgrims come through every day, stopping for an hour or so and then continuing up the valley to the east. As a result, the pilgrims often do not spend as much time in Kagbeni as do the other types of tourists.

Then there are the trekkers who are on their way to Upper Mustang, either by foot or by jeep. They have a Nepali trekking guide with them, and most stop in Kagbeni for the night before moving on. The majority of these groups are White Europeans and North Americans, often traveling as a family or a group of close friends. Over the course of the five weeks that I was in Kagbeni, I encountered only three pairs of tourists who were not European or North American, and they were from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Argentina. Otherwise, the tourists moving through the village were very clearly from Western European countries (Portugal, Switzerland, Holland, and Spain) or were from the United States and Canada.

Finally, the third kind of tourist in Kagbeni is the group that the woman at the gompa belonged to: the Annapurna Circuit trekkers. Living on a budget, they have been backpacking for at least a few weeks, almost done with the circuit. Trekkers leave from Pokhara in the foothills of the Himalayas, walk up through the valley of Manang, cross over Thorong-La pass, and then quickly pass through Kagbeni and Lower Mustang on their descent back to Pokhara. They tend to spend the night in Muktinath, and stop in Kagbeni for an hour or two to grab lunch and see the gompa on the way to Jomsom. This is in a way the opposite of what the pilgrims going to Muktinath from Jomsom do, though both groups make a pit stop in Kagbeni. These people, again, are predominantly White Europeans and North Americans. The majority of them do not travel with a guide, and most are solo travelers. Occasionally there are small groups or pairs, or people who have become friends on the trail and stick together for the remainder of the trek. For the most part, this is also the youngest group of tourists, though all three groups include a wide range of ages.

In addition to tourists, other foreigners travelling through Kagbeni include people associated with National Geographic, independent film makers, and scholars hoping to record and preserve the ways of life there. Travelers to Mustang bring with them certain expectations based on popular media, travel writing, and scholarship about the region. Monks chanting. Sky burials. Trekking. A “Forbidden Kingdom” set apart from the rest of the world. A “pure” Tibetan culture. Whether or not these expectations match with reality, the assumptions that outsiders bring to Mustang shape the way that they understand the landscape and people. In addition, these assumptions inform how Loba interact with tourists, artists, and scholars, building on the stereotypes already in place.

Observing the interactions between locals and tourists, it becomes clear that tourism in Kagbeni is a site of friction. The most prominent buildings, with the exception of the gompa, are hotels. The economy relies largely on trekkers coming through the town, and even when they do not stop, the foreigners make themselves known with a burst of sound. Jeeps trundle through the main road at the center of Kagbeni each day, blasting Bollywood songs and honking at construction vehicles to get out of the way. Idling engines overtake the bubbling streams flowing through the streets. To the trekkers moving through, Kagbeni is merely a stopping point in a much longer journey. This interaction with Kagbeni mirrors its historical role as a stopping point for trade. Global frictions echo throughout history, manifesting in new ways with different actors.

Western Exceptionalism

Sitting quietly in the solarium at the hotel one afternoon, I watched in dismay as a group of 14 loud college students tumbled inside, followed by two professors and a handful of Nepali staff members. I had gotten used to the quiet of being one of the only guests at the hotel during my stay in Kagbeni, and was not looking forward to the noises that these Canadian students brought with them – especially the playing of music on portable speakers or phones on an otherwise peaceful afternoon.

The group remained in Kagbeni for two nights. I remembered noticing the group at the Kag Chode earlier that day, I could tell that many of the students (about twelve women and two men) returned to the hotel upset by their experience there. Teaching in a second-floor classroom, I had first seen them when they entered the courtyard to meet with one of the monks and receive a tour of the gompa complex. They had all seemed cheerful then, so why were the women so upset when I encountered them at the hotel that evening?

I discovered the reason for their disgruntled attitudes over dinner. Apparently, while touring the old monastery building, the group had been told that only the two male students could enter the secret room on the third floor, because the women were “polluted.” This made some of the students extremely upset, as they did not understand why the monks would not make the exception to allow them to see the special chamber where the gods are kept in order to heighten their learning experience. They had come here as part of a class, after all. Part of their frustration was due to the bluntness with which they were told they could not go in, while another piece of anger was directed towards the monk who had given the tour and barred their entry. Because this monk was younger (he was 21) and was not the khenpo or another more highly educated monk, the students felt that he did not have the authority to tell them where they could not go. Two students even returned to the gompa the next morning with their professor, in order to talk to the khenpo about what happened and to see if there was any way to go inside.

This is an example of Western exceptionalism, following the belief that because the student group was not a part of the Buddhist tradition practiced at the gompa, they should not have to follow the same rules. Weeks later, one of my students explained to me that women are in fact allowed into the room, but only after being purified in a ceremony. The primary reason why women are considered polluted in Buddhism and other South Asian traditions is because of menstruation and the perception that blood is a signifier of impurity. While many communities are shifting the rules around women, each monastery maintains rules differently. In their assumption that they could travel wherever they wanted with no consequences, the women in the university group held their own cultural and feminist beliefs over those of the local community’s.

This mode of interacting with Kagbeni, moving through the space as if it was completely separated from the reality of life elsewhere, was further expressed by the use of sound among tourists. Throughout my time there, tourists and other visitors introduced their own noises into the Kagbeni soundscape, making their presence unquestionably known. The student group from Canada played music on their portable speakers the entire time they were at the hotel. Tour groups ranging from six to twenty people were accompanied by gleeful screaming, laughing, clapping, complaining, shouting at friends to look at things, making skype calls, and playing instruments. And don’t forget the honking of cars and busses that transport the groups, coming from the center of town. These sounds quickly take over the relative quiet of the town, with little regard to the space that they take up. Once again, the politics of space and sound come into play, as the Top-40 hits from North America enter the soundscape of Kagbeni with a boom and quickly drown out everything else.

Sounds of tourism in Kagbeni are therefore another space where we can see the interactions of global friction and imagined boundaries. Sound provides not only points of contact and appropriation, but also allows for participation by the excluded (LaBelle 2010: xiv). In this context, tourists who feel excluded or out of place in Kagbeni create space for themselves through sound. Because sound functions as a way to build connections, to take up space and assert belonging, it becomes a strategy when people feel out of place. Songs from home played on portable speakers mediate the tourist experience as they engulf the space.

Pilgrimage

To the west of Kagbeni, a half day’s walk up the road, lays Muktinath. This site is a place of liberation for Hindus, and is one of a series of sites that Hindus visit when a family member dies. As discussed briefly above, Guru Padmasambhava visited the site, but it is also a space where Dakinis (sky goddesses) can be found in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. On Padmasambhava’s journey through the Himalayas, “he practiced religious teachings and often left behind physical marks or traces in the landscape, such as footprints, handprints, or stones in special shapes” (Oestergaard 2010: 65). At Muktinath, he left a statue of himself which remains there today in his quest to spread Buddhism. In the Chhungsi cave near Syangboche, self-emanated forms appear out of the rock walls which signal Guru Rinpoche’s stop there in the 8th century. Landscapes are a critical piece of Tibetan Buddhist pilgrimage. Oestergard explains that the importance of landscape in pilgrimage is because

When alleged mythological episodes are supposed to have taken place in landscape, mythological time intersects with geographical space, creating a sacred site, a location that is separated from other geographical locations. A Tibetan pilgrimage site is therefore not only spatial but also temporal, integrating geographical space and narrative time in a particular place (Oestergaard 2010: 64-65).

When alleged mythological episodes are supposed to have taken place in landscape, mythological time intersects with geographical space, creating a sacred site, a location that is separated from other geographical locations. A Tibetan pilgrimage site is therefore not only spatial but also temporal, integrating geographical space and narrative time in a particular place (Oestergaard 2010: 64-65).

The mapping of mythology onto the landscape does not have a purely religious function in the sense that this mapping is also part of a larger strategy and marketplace. Ian Reader (2013) argues that pilgrimage has long been an expansion strategy, creating important sites near people who may be converted. Muktinath, and other sites in Mustang like the Chhungsi cave, are likely carefully chosen spaces.

The intersections between Hinduism and Buddhism at Muktinath appears on the surface to be an example of what many foreigners applaud Nepal for: peaceful relationships and acceptance between religions. This popular optimistic understanding of religion in Nepal does not account for the strategy of claiming sites, nor the history of Nepal as a Hindu kingdom in which all other expressions of religion were shaped to appear more Hindu. Muktinath itself presents an example of this. By placing an emphasis on the Hindu interpretations of the site, it becomes more legitimate, it gains more authority. Although Buddhists claim the site as important, and have their own gompa there, the complex is primarily focused on Hindu practices, linking it to the national majority and historic processes of Hinduization.

While Muktinath became well known for its prominence as a religious pilgrimage site, it is impossible to ignore the number of trekkers and other tourists walking around the grounds. The site lays directly on the Annapurna Circuit, in addition to the bus routes used by the Hindu pilgrims from Nepal and India. The religious nature of the site, its fame and benefits, would not be promoted without the level of tourism and consumerism associated with it. Reader argues that the sacred “is not separate from but grounded in the realms of the mundane, profane and mercantile, which are themselves integral elements of in the construction and shaping of pilgrimage and thereby of the sacred” (Reader 2013: 195). With this site in particular, the entanglement of religion and tourism becomes apparent. Trekkers on the Annapurna circuit do not necessarily go to Muktinath because of their religious beliefs, or because of the mythology around it, but because it is promoted as an important highlight of the trek. At the same time, the shop and hotel owners near Muktinath are not necessarily there because of their religious beliefs, but also because of the commercial opportunities and commitment to local communities (Reader 2013: 110-111).

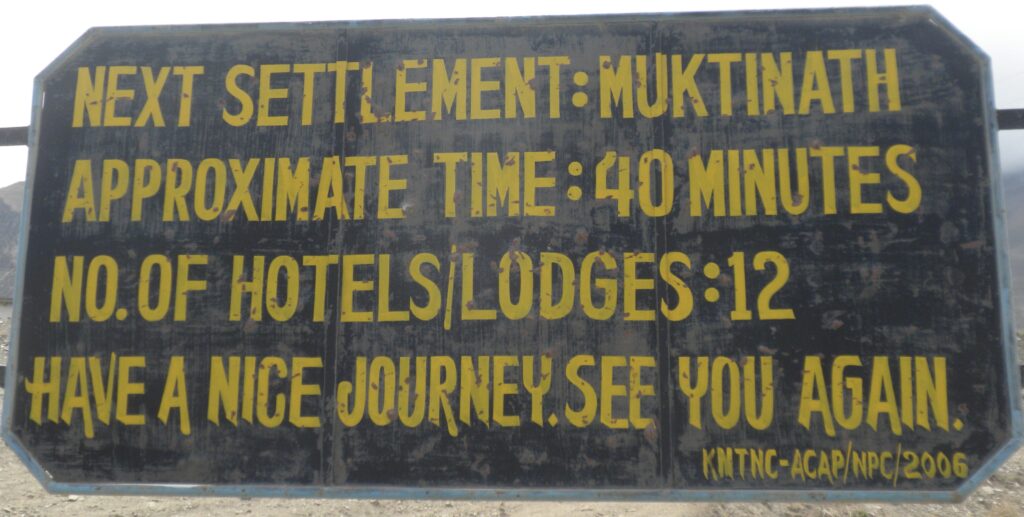

In talking to Kunga, I learned that the towns surrounding Muktinath have grown quickly over the last fifteen years since the road has been built, and that there are now much larger hotels surrounding it. This is promoted to trekkers and other pilgrims alike using signs such as the one pictured above. Pilgrimage routes throughout the world are promoted as hiking destinations in order to increase number of people visiting sites, and Muktinath is no different. Many tour companies in Nepal offer a variety of treks through Mustang or around the Annapurna Circuit, each with varying degrees of accommodations. In Mustang, trekking either the circuit or to the city of Lo is the main appeal, the improvements to the road have a made big impact on the way that people interact with and perceive the region, and the types of people that visit. After all, transportation is an accessibility barrier (Reader 2013), and Mustang is now accessible by jeep, bus, plane, and even helicopter. In fact, due to the dusty nature of the road, most “trekkers” now travel by jeep for the majority of their journey in Upper Mustang, stopping to go on a day hike or two along the way.

With the opening of Mustang, the economy of the region has shifted from being predominantly agriculturally- and trade-based to having a higher reliance on tourism. Marcy Vigoda explains that this is a common shift in areas where Western influence becomes widespread. It “alter[s] the nature and structure of society and undermine[s] traditional cultures” (Vigoda 1989: 33). What’s more, “where tourism has become a lucrative sector of the economy, natural resources have been over-exploited” (33). In Nepal, Vigoda estimates that one trekker (with their porters and guides) uses up the same amount of firewood as ten Nepali (34).

According to data posted in the Kagbeni ACAP office, this shift in Kagbeni towards a more tourism-focused economy began to occur in 1992 as the first tourists came to the area for trekking opportunities, increasing in number from 483 trekkers in 1992 to 4146 in 2014, and 3918 in 2016. The Nepali government built a road through Mustang around 15 years ago, and has since been expanding and improving it. This road is meant to connect India and China for easier trade, but it also makes it easier for people to reach places like Muktinath without stopping in towns along the way. Thus, bus loads full of pilgrims arrive in town for an hour or two to rest and grab a bite to eat or see the town, and then immediately head off to the site without spending the night here in Kagbeni or in the other smaller towns further up the mountain.

The creation of the road through Mustang has not only had an impact on the politics of the region as discussed previously, it has also greatly changed the way that tourism operates in Mustang. Prior to the road being built, there were trails between the villages that people would travel by on foot or on horseback. This made the region immensely popular for trekkers, who would walk village to village, spending the night in tea houses and hotels along the way. Construction on the road began in the early 2000s. While this made the region more accessible both in terms of ease and cost of travel, it also created a much less pleasant habitat for trekkers. The wider roads and frequent construction efforts kick up clouds of dust in the strong winds that sweep through the gorge, sending it directly into the faces of trekkers. As a result, less tourists come to know the area through walking, opting instead to take a jeep or even a helicopter from place to place (with a few day hikes incorporated along the way). This means that the tourists are not stopping in as many towns, thus not pumping as much money directly into the region through the people who live there.

The quietness of trekkers has been replaced by jeep horns and helicopter blades as Mustang further becomes a destination for the elite. High-end tourists paying expensive fees to travel through the area often (though not always) bring with them a sense of entitlement, which means that there is no hesitation or thought given to the amount of space (physical and sonic) they take up.All of these forces (the pilgrims, the trekkers, the wind, the road, the narrowness of this spot in the gorge) have come together to change the way that Kagbeni interacts with tourism. Even on the Annapurna circuit, many people now walk from Muktinath directly to Jomsom (the next larger town down river and where the small airport is located), quickly wandering around the streets of Kagbeni before moving on. The people who live in the village all comment on this, saying that the road is good and bad, but that it has certainly ruined trekking in the area.

Representing Mustang

Discourse surrounding Mustang as a “Shangri-La” contributes to its separation from the rest of Nepal, this time as an otherworldly place. While this language is often used by tourism agencies to promote trips to the region, scholars and artists also play into this language. In paintings, photographs, and documentary films about Mustang, the region is consistently described as mysterious in order to create intrigue and interest among public Western audiences.

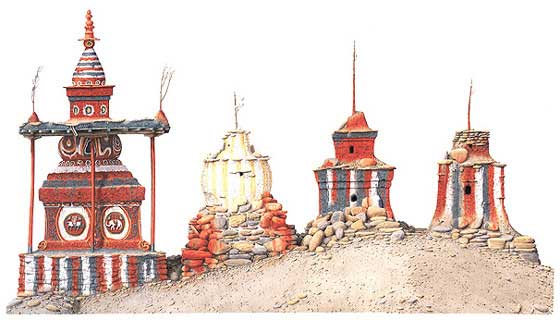

Robert Powell, an artist known for hyper realistic paintings of buildings, provides an example of how characterizations of Mustang play into its exceptionalism. Powell began creating a series of paintings depicting buildings in Mustang in 1992, immediately after the region was opened to foreigners. The paintings focus on the structures and landscapes of Mustang, removing people entirely. They are highly scientific (Powell took samples of clay from the surrounding area to ensure that the colors would be accurate) and yet also depict a romanticized vision of Mustang. The entire introduction to the collection published in Earth, Door, Sky, Door revolves around how magical Mustang is, and how religion is ingrained in the landscape. Phrases describe the landscape as “stripped of succor, dry, windblown, dramatic, and overwhelming in scale. Its immensity, its unpredictable and often malevolent climate, dwarf human activities” (Vitali and Powell 1999: 7). While it is true that religion maps onto the landscape of Mustang, as discussed in Chapter 2, Powell’s depiction of buildings and landscapes devoid of human life make these claims seem more focused on the mystical feeling of Mustang, rather than the reality for people who live there.

Peter Gottschalk identifies this phenomenon of representing spaces without human subjects in Religion, Science, and Empire. The Daniells were well known in the 1790s for painting “picturesque” and “scientific” images of India which could then be consumed by people at home in England, as well as used to perpetuate specific ideas about India and Indians (Gottschalk 2013: 142). As Gottschalk describes, “the art of Thomas and his nephew derived from two competing impulses: the imaginative and Romantic flourishes demanded by the picturesque and the empiricism and realism favored by a coalescing scientism” (145). Two hundred years after the Daniells painted in India, Powell becomes a similar case in Nepal. His attention is focused solely on structures, removing all traces of human activity beyond a singular building or landscape. Each painting shows one subject, surrounded by pristine white, thus pulling each image out of the context of the surrounding world. While some see this style as “formal perfection” (Vitali and Powell 1999: 11), it effectively contributes to a wider discourse of romanticizing the region even as it does so scientifically.

Kevin Bubriski addressed some of these same issues in his series of black and white photographs of Mustang taken in 2016. Mustang in Black and White provides a series of photographs taken from Kagbeni to Lo Manthang, capturing moments of daily life in the region. Rather than fall into the same trap as Powell, Bubriski’s photos, along with Sienna Craig’s text, provide a better balance between the power of the landscape, and the people who live there.

In the materials about Mustang, sight as the primary sense is immediately obvious. Robert Powell’s paintings, National Geographic spreads, and Kevin Bubriski’s photos all capture what they see as the essence of the region through static images. The Nepal Tourism Board made a video to promote the region, and many trekkers over the years have created travel videos of their time in Mustang as well. No one that I have encountered has presented Mustang through sound, though authors writing about Mustang frequently mention the tinkling animal bells and the creaking prayer wheels. This dynamic conveys a disconnect between what visitors to Mustang understand to be primary, and how the locals interact with sound on a daily basis.

The “Forbidden Kingdom”

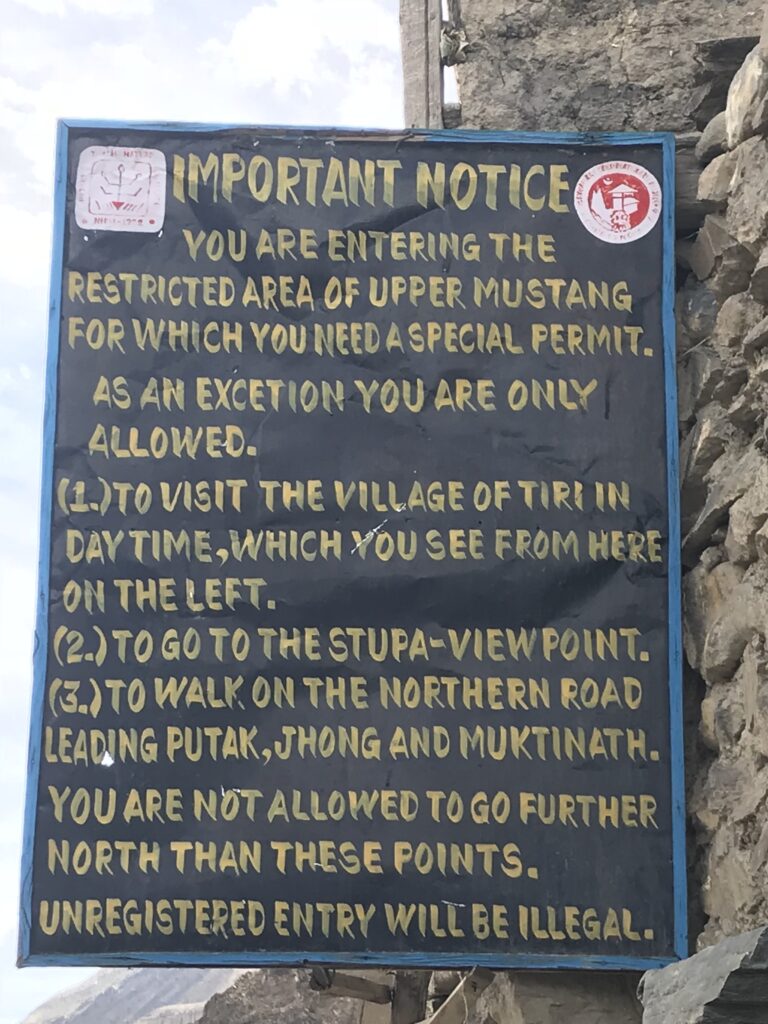

In books, news articles, and on travel company websites, Mustang is often referred to as “The Forbidden Kingdom.” This title refers to the period of time between the 1960s and 1992 when the region was restricted to outsiders, and remained a recognized Kingdom. Even after the region was opened in 1992, the number of foreigners allowed in remains low, due to the extra expenses of the permit for Upper Mustang. Even now, as numbers of tourists continue to increase, the name sticks. The widespread use of this name alludes to a past Mustang, and contributes to the ideal of the region as being an exotic, elite, adventurous destination.

One trekking company promoted its trip to Mustang like this: “Join our … team in this majestic journey to the mystical land of Lo-Manthang!” (“Forbidden Kingdom/Upper Mustang Trek”). Another company promoted the Upper Mustang trek, saying “entering Lo Manthang through the town gate is like stepping into a different world” (Great Himalaya Trails). This website also informed readers that Mustang has a “highly preserved Tibetan culture” with an “unspoiled nature.” This language paints the picture of Mustang as forbidden, mystical, or other-worldly, adding to the sense of mystery around the region and appealing to tourists with a sense of adventure. Unfortunately, it also contributes to the perception that Mustang is stuck in the past, and that the region is somehow separate from the rest of the world.

These quotes highlight another idyllic misconception that both tourists and scholars have about Mustang: that it has a more “pure” or “authentic” Tibetan culture than Tibet itself, due to the Chinese invasion in the 1950s. Upper Mustang as an extension and stronghold of Tibet is promoted further by blogs from trekkers describing their experiences. These blogs often greatly romanticize the region, and the authors make claims such as “trekking to a mountain desert in Nepal is just like visiting ancient Tibet” (Fund 2015). Or “Mustang is one of the last places in the world where traditional Tibetan culture remains intact” (Ornitz 2013). This widespread belief further separates Mustang from the rest of Nepal as well.

Using this language to talk about Mustang creates a specific idea about what the region is. The title “Forbidden Kingdom” romanticizes Mustang, highlighting the fact that it is difficult to get there, and making visitors seem more accomplished for having done so. This then changes the types of interactions that tourists have with locals, as they carry the pride and entitlement of being able to access the region. It also plays into Orientalist dynamics, where the Western tourist is superior to the rural community they visit. This is evident in the ways that tourists take up sonic space in Kagbeni. University students and high-end tourists are more likely to take up physical and sonic space than are budget trekkers on the Annapurna circuit, which matches the amount of money they spend to be in the town. With their feeling of entitlement – they paid for a permit to be here, after all – people have no qualms about spreading out and making the town their own.

Not only does this title make visitors experience Mustang in a specific way, it also does work to distance the region from the rest of Nepal. With the boundaries of the restricted zone clearly demarcated on maps, with the boundaries of ACAP surrounding it, there becomes a clear point at which you cross from the rest of Nepal (or Lower Mustang) into Upper Mustang, the Forbidden Kingdom. Because of the extra permits required, Upper Mustang becomes an elite destination for high-end tourists while remaining on the periphery of Nepal’s development projects.

With this in mind, it is clear that tourism in Upper Mustang is inherently linked to political and religious imaginations of the region. The entitlement tourists bring, the pilgrimages they embark on, and the sounds they contribute to Kagbeni each serve as a reminder for the ways in which Kagbeni is linked to global forces and frictions. In each of these interactions, political and religious perceptions of Mustang play an important role in mediating the experiences and interactions between tourists and locals. From these examples, it is clear that it is impossible to consider the impacts of tourism on Kagbeni without also taking into consideration the political and religious context surrounding it, especially following the Rana regime beginning in the 19th century. Although tourists and other foreigners have only been allowed into Mustang for little more than the last two decades, their interactions do not exist in a vacuum.

By calling the people there more purely Tibetan than Tibet, visitors ignore the Nepali part of Loba identity and potentially create more of a divide between the two. In addition, they collapse Loba and Tibetan identity, as if the two are identical. Another issue arises because this thinking implies that Tibetan culture no longer exists in Tibet, because of the Chinese invasion in the 1950s. In other words, this discourse imagines Tibet as a place or culture in the past, and not wholly of the present. This kind of discourse is what pulls many people to travel to the area, since it is seen as a space of exception, once again creating an idea of Mustang as a location of difference. The authors of Mustang in Black and White address this issue nicely, arguing that places like Upper Mustang “certainly are part of the broad sweep of Tibetan civilization, but casting them as authentic outposts of a generic Tibet closes our eyes to the details that make them something other than just that” (10). Upper Mustang is not just a place reminiscent of Tibet, stuck in the past. It is not just a magical landscape, devoid of life. Thinking so not only plays into historical power structures painting Mustang as a borderland, but also neglects the agency that Mustang communities have in global processes and frictions. Friction is not possible with only one side, and friction is required to move forward, Tsing reminds us (2005: 6).

In the preface to a series of essays on the Himalaya, Ruskin Bond reminds us that “living in the mountains is not a romance for everyone” (Bond and Gokhale 2018: xiii). Yet from the discourse surrounding tourism in Mustang, alluding to Shangri-La, saying that it is a place where you can find pure Tibetan culture, and calling it the “Forbidden Kingdom,” the region is constantly romanticized. These narratives of Mustang as different from the rest of Nepal help promote it as a unique travel destination but strip it of its complexity. They focus on the desirable aspects of Mustang, painting the people as if they are relics of the past. This is part of a wider discourse around cultural preservation, and the need to save dying traditions. Mustang, in its uniquely imagined state, has been the focus of many cultural preservation projects in recent decades, with varying degrees of success. Cultural preservation for the sake of tourism or for the sake of global trends has not been nearly as successful as community-based projects. Looking at the state of tourism in Kagbeni it is possible to see why this might be the case. It is this issue that I turn towards next.