Culture, Landscapes, and Identity

Religious Landscapes

The Smell of the Cows

Team Tashi Delek

Reshaping Mustang

Towards the end of my time in Kagbeni, I walked into the lounge area of the hotel I was living at to find Aama laying on one of the benches, reading quietly aloud to herself. Aama is the matriarch of the hotel, the mother of Kunga. She visits the gompa on occasion, but not every day like some of the older women in town do. You can often find her sitting in the sun, working on weaving with the resident cat in her lap. That day, the sun streaming in from the southern windows fell softly on her book, which held words written in Tibetan script. Plopping down across from her, I pulled out some reading of my own.

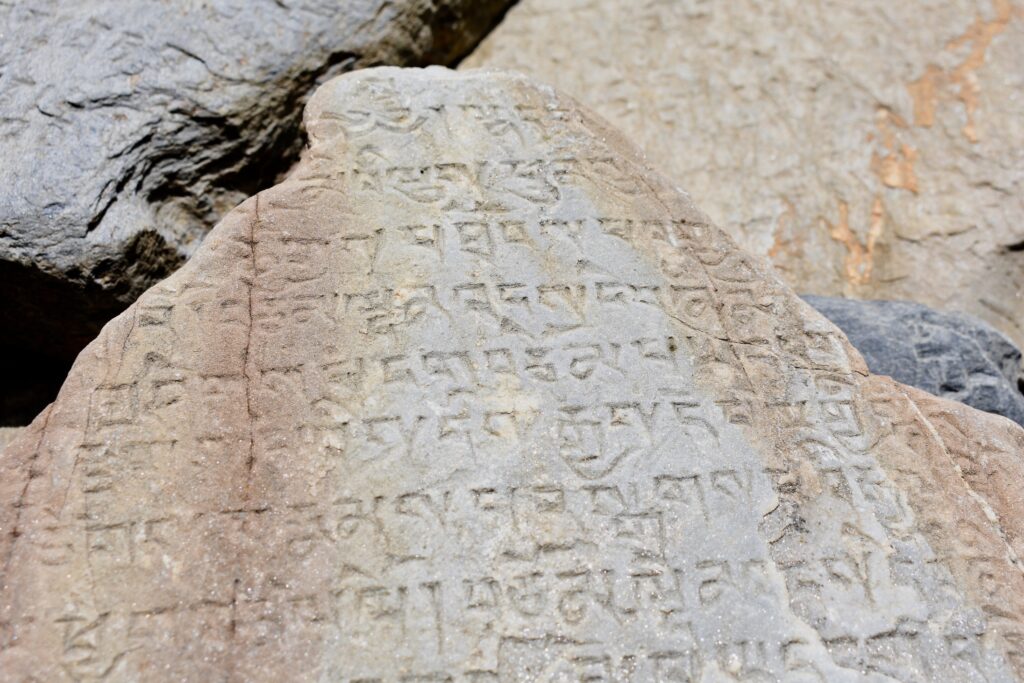

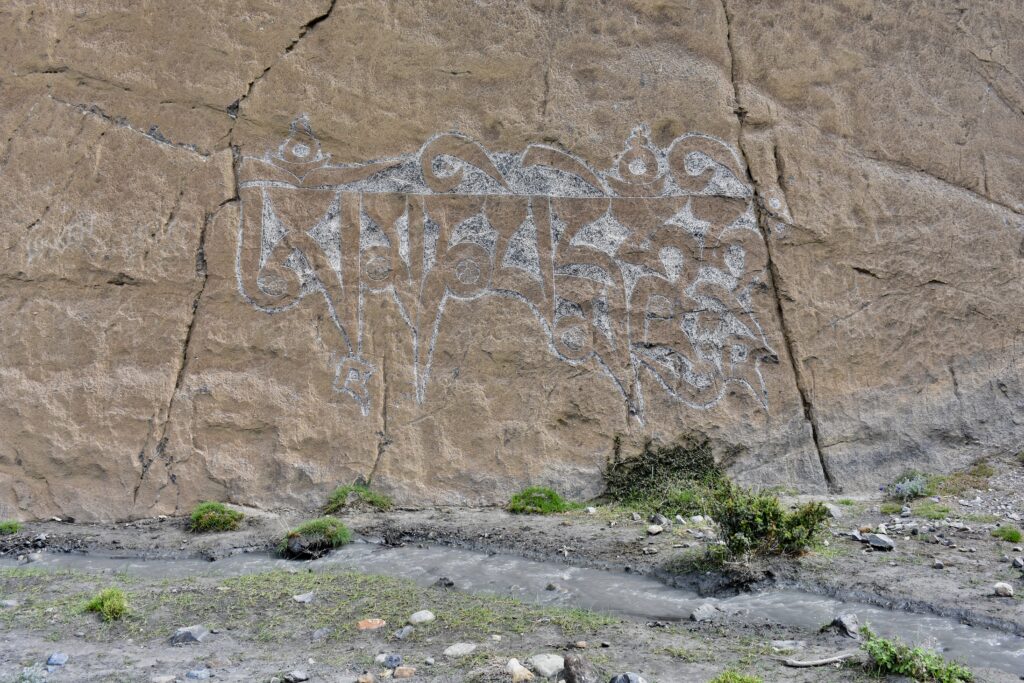

Listening to the soft cadence of her voice, a few words caught my attention with their familiarity. Aama repeated the phrase “Om mani padme hum” every few lines, making me wonder if the book was a religious text. Om mani padme hum is the most common mantra you will see or hear in Mustang. The mantra has gained such popularity in part because “all of the teachings of the Buddha are believed to be contained in this short, six-syllable mantra, which does not require initiation by a lama and is the most widely used of all Buddhist prayers” (Buddhist Music of Tibet). The mantra is aimed at the compassion of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, with hope that repeating the words will bring the speaker a swifter path to enlightenment through removing all attention to desire. “Behold the jewel of the lotus” is carved into stones placed on mani walls, metal and wood prayer wheels, and cliff faces themselves. People mumble the phrase to themselves as they sit in the sun, twirling a hand-held wheel in their hand, or as they walk past a prayer wall, spinning each wheel as they pass.

In its written form, the mantra appears in Tibetan characters. The spoken phrase, however, remains in its original Sanskrit. While many other mantras and texts are translated into Tibetan from Sanskrit, Om mani padme hum remains. The khenpo at Kagbeni’s gompa explained that this is because the sounds of the mantra are the most important, and that the phrase sounds strange when spoken in Tibetan. The chanting of the mantra becomes important “not by what it describes or cognitively reveals but by the complex vibration or feeling tone it creates in the practicing person” (Coward and Goa 2004: 6). Thus, there is more power in the sounds of the spoken Sanskrit words than in their Tibetan equivalent. Om mani padme hum stands out from other mantras and texts in this way, as Sanskrit is otherwise only spoken in formal circumstances such as in a recitation performance at the consecration of a new monastery building. In the case of the upcoming Kag Chode Monastic School consecration, for example, a piece in Sanskrit was to be performed by a student in order to pay homage to the original roots of Buddhism in India.

The importance placed on sound is not unique to Kagbeni or to Tibetan Buddhism, but the way that it manifests in Kagbeni is linked to a wider cultural and religious landscape. In Tibetan Buddhism, “certain categories of Buddhist sacra are ascribed the power to liberate through sensory contact” (Gayley 2007: 459). This means that there is a range of benefits in sensory contact with mantras, even including the claim that liberation is possible through seeing, hearing, tasting, wearing, or otherwise encountering certain texts, objects, and structures (Gayley 2007: 460). The impacts of this can be seen across the landscape of Upper Mustang, where the world is reshaped through interactions with mantras and the divine.

Between bites of thukpa later that evening, Kunga explained to me that when people in Kagbeni reach 60 years old, they become much more religious. Aama, his mother, is 61, and has thus reached this point in her life. He explained that she is reading religious texts, trying to learn more about Buddhist teachings now that she is getting older. I asked Kunga if he thought he would become more religious when he reached Aama’s age.

He chuckled in response. “If I’m still alive.”

Despite Kunga’s distancing of himself with this comment, it is impossible to remove the impact of religion on his life. The sounds of Tibetan mantras, for example, were not a new feature in the household. In fact, I had been hearing recordings and videos of monks performing ceremonies since my first day in Kagbeni. In the afternoons, it was not uncommon for a group to form around a smartphone in the kitchen, playing a video of a puja on YouTube. Other times, I would hear videos of mantras-turned-songs being played during breakfast, always on someone’s phone. Once, a group of women from around the town gathered to perform a household ceremony in the prayer room upstairs, chanting mantras late into the evening [sound clip of household ceremony].

And that is only within the walls of his hotel. Stepping outside, the entire landscape becomes transformed as prayer flags flap in the wind, as the voices of the monks performing their daily puja in the gompa are projected from loudspeakers.

Throughout my time in Kagbeni, Kunga routinely distanced himself from his own religiosity and connection to Loba culture when we talked. This could have been in part because I was only visiting, was there for research, and hadn’t known him for long. The presence of religion or tradition in Kunga’s life was always described in relation to others’, such as when he informed me that people in Kagbeni, or in Lower Mustang, care much less about tradition than in Upper Mustang. He did not deny his beliefs, but always pointed to other people who he believed held more.

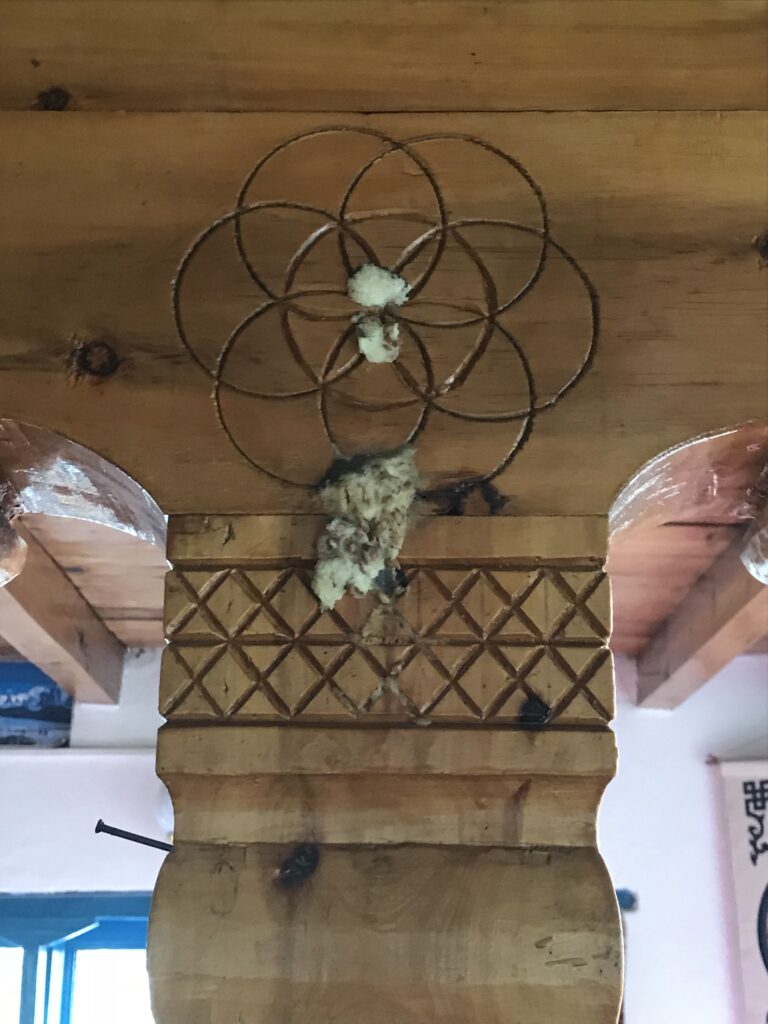

Even with this distancing, his life was not entirely absent of these things. It was often his phone which played the videos of pujas in the kitchen, and he occasionally went to dance practices in preparation for a ceremony which would occur the following month. The pillars of his hotel are all marked with butter and herbs placed there by the monks, and a Bon guardian presides over the front entrance to the building. Buddhist chörtens and their Bon counterparts are both found on the roof. One morning, I walked downstairs to find one of the older monks in the kitchen talking to the staff. Along with some of the other local hotel owners, Kunga occasionally went to the gompa in order to meet with the khenpo in preparation for the upcoming consecration ceremony.

This distancing from religion is not unique to Kunga, who is now in his early 40s. The people who visit the gompa most frequently are women Aama’s age or older, often at the same time every day. Looking at the people who live in Kagbeni, there is a clear divide in the generations. Women above the age of 40 most often wear the traditional Loba clothing, while younger women rarely do. This shifts as you move northward up the Kali Gandaki closer to the capital of Lo, where more people wear the traditional Loba clothing. As Kunga explained, this is because Upper and Lower Mustang are very different, and that people like him down at the border between the two in Kagbeni don’t care as much about the traditional things.

Kunga’s comment about people becoming “more religious” as they age points to a divide in how people think about religion. If religion is expected to be primarily text-based, then he is right that Aama is becoming more religious as she begins to read more Tibetan Buddhist teachings. This understanding of religion leaves out the impact that it has on every-day life. For lay people living in Kagbeni, the actual texts are not important. At the same time, students at the monastic school have classes on the dharma, the teaching of the Buddha, and there is a ceremony that involves carrying the physical books of the Buddha’s teachings around the boundaries of the town. In other words, the texts are not unimportant or irrelevant to the presence of religions in Kagbeni, but they are not the focus of lived religion there. Sound arguably becomes more important than the texts in this setting, as it reshapes the landscape and is used by monks and lay people alike. Whether or not lay people know the reason for the power in speaking certain words like om mani padme hum, the phrase is a piece of daily interaction with the divine.

Kagbeni lives at an interesting set of crossroads. There is the physical crossroads built by the government, bringing traders and trekkers north to Lo and pilgrims east to Muktinath. There is the cultural divide expressed by Kunga, separating Upper and Lower Mustang. This divide is not only about commitment to tradition, it also implicates the conflicting Nepali, Tibetan, and Loba identities. At the borders between these categories, people in Kagbeni are reshaped by the shifting factors every day.

Religious Landscapes

The primary religious influences found in Kagbeni are Tibetan Buddhism, Bon, and Hinduism. All three mingle and overlap, sharing sites, beliefs, and practitioners. In all three, the landscape is an essential feature. Landmarks like mountains are said to be the homes of gods, and the convergences of rivers are sacred spaces. These religious landmarks in turn map onto real physical locations, allowing spiritual authority over key sacred sites to be translated into political power (Ramble 1995: 93). Upper Mustang presents a good example of this relationships between sacred and political space, as Lo Manthang is also the seat of a principal territorial deity in local cosmologies, and the surrounding areas are home to lesser gods (Ramble 1995: 91). The seat of political power in the region is also the seat of religious power. This dynamic of mapping religion onto the landscape is not unique to Kagbeni nor to the religions present there, yet it remains an important aspect of the Tibetan Buddhist and Bon ontologies. In addition to the daily practices of spinning prayer wheels or attending to the household gods, this shows us that the entire landscape of Mustang is covered in and changed by interactions with religion.

At the river

convergence south of the gompa, a

small park of sorts holds both Hindu and Buddhist shrines. Hindu pilgrims and

novice monks from the monastic school wash themselves in the water as the smoke

from incense flows over them. The prayer wall in the gompa complex stretches down the bank, right to where the two

rivers meet. Prayer flags are wrapped in tree branches and hang from the

bridge. This site – right next to the main road through town – claims the

attention of passers-by. It’s colorful, loud, and often bustling with activity.

Bells are rung by pilgrims passing through, mingling with the beeping horns of

jeeps and the Bollywood music spilling from the windows of buses. Along with

the chörtens in the streets and the

monastic school up the road, it is what most people passing through would point

to as markers of

Kagbeni’s religious nature.

An emphasis on physical, visual, markings on the landscape negates the way the landscape of Mustang has been shaped for centuries by various mythologies and sonic vibrations that claim space. In the Tibetan Buddhist ontology, “Tibetan architecture, landscape, and religious beliefs are woven together, forming a sacred realm. The theme of the mandala is present everywhere one goes; as a spiritual vehicle and a general model” (Xu 2010: 182). The chörten is one structure which weaves together these themes into the form of a mandala. As Xu explains, the physical structure of a chörten is a three-dimensional representation of a mandala, a model of the universe. These structures are sprinkled across the landscape of Mustang, and throughout Kagbeni. Varying in size and style, they are reminders of the nature of the universe, and “of the spiritual realm in which Mustang is embedded” (Bubriski et al. 2018: 19). Similarly, the music used in pujas creates a mandala through the way sound is created (Ellingson 1979).

Because of this emphasis on the land as being a home to deities and itself a mandala, Tibetan Buddhist teachings often emphasize the proper use of land in order to prevent pollution, especially of water resources. For example, by describing how a toilet should be built to promote a healthy environment, or promoting the planting of trees to prevent deforestation (Vigoda 1989: 26). While water is generally sacred, or purifying, in the Tibetan landscape it takes on the additional context of being scarce, and thus even more important for sustaining life.

One practice frequently associated with Mustang is Sky Burial. This death ritual is often described in documentaries and tourism materials as something that keeps Mustang linked to the past. Vigoda explains that this is yet another example of a religious practice reacting to the conditions of the environment. She says:

[Sky Burial] is carried out at the tops of hills and mountains, where bodies are chopped up and fed to the birds… [it] is indicative of how the lack of natural resources, and the Buddhist idea of the interdependence of all things, are manifested in a religious custom (Vigoda 1989: 29).

In recent years, however, the practice has died out almost completely. There are a few reasons for this. First, Himalayan Vultures are now an endangered species. These giant birds who once played a large role in disposing of corpses were impacted by the use of DDT in India, and have thus decreased in population considerably. I noticed a distinct lack of vultures on my second visit to Mustang in 2018, whereas my group had gleefully spotted a few of the birds two years before.

The second reason for the deemphasis on Sky Burials is linked to global trends of modernization. Traditional practices, especially around death, are often looked down on or seen as backward by more powerful, ‘modern’ or ‘developed’ countries. Even though Mustang is remote and difficult to navigate, it has been linked to trade networks for hundreds of years. Many of the wealthier families in Mustang have houses in Kathmandu as well, and often travel outside the region. Seasonal jobs bring people to India and Tibet for trade or construction work, and children are often sent to school in Pokhara or Kathmandu. As a result, there are many ways that the communities of Mustang are shaped by global trends, even without taking the impact of tourism into consideration.

At the same time, the imagination of Mustang as a stronghold of Tibetan culture is one of the main draws for tourism in the region, and there are many groups which are trying to preserve the culture of the region. The perception that Mustang’s culture and language is unique and under attack by globalization and modernization is prevalent among NGOs internal and external to Nepal. While there are some groups like the American Himalayan Foundation that strive towards cultural preservation, Sky Burials are not the focus of preservation initiatives. On the other hand, the few Sky Burials that do still happen today have become a draw for tourists who want to see a different culture in action; preservation for the sake of tourism has a different sort of friction.

While the Buddha’s teachings make an impact on practitioners’ relationship to the land, so does the presence of the other deities in the Tibetan Buddhist and Bon cosmologies. These deities inhabit the sky, atmosphere, and earth, and can be both benevolent and wrathful (25). The domains of these deities recognized in Tibetan Buddhism and Bon map onto the physical landscape of Mustang, and are mirrored by the structures built. In Mustang, the emphasis is placed most heavily on the mythology of Guru Padmasambhava, or Guru Rinpoche. In fact, the figure of Guru Rinpoche is more important than that of the Buddha, and it is his likeness that sits at the altar of some monasteries.

Muktinath, the pilgrimage site to the east of Kagbeni, is one site where Guru Padmasambhava is said to have stopped, thus making it an important Buddhist site in addition to its importance for Hindu pilgrims. A few days’ walk north, outside of Gami village, the longest mani wall in Nepal sprawls across a plateau, marking the site of a battle between Guru Padmasambhava and a demoness. The canyon walls are blue and red with her blood, and a chörten built in the 8th century safeguards her heart, cut out by Guru Padmasambhava.

In addition to shaping the physical environment with chörtens, monasteries, sound, and prayer flags, much of Tibetan Buddhism focuses on turning inwards. In the harsh landscape of high-altitude desert, methods of self-realization are emphasized in order to have a chance of escaping samsara, the cycle of rebirth, in a future life (Gualtieri 1983: 170-1). As discussed above, this often involves sensory contact with mantras, whether it be chanting them or carving or painting them on rock walls. Peter Crossley-Holland explains another aspect of the mantra’s significance. According to him, “a mantra is a symbol for the divine being it is said to embody, but it is also believed to be more than that: it is believed to be an actual emanation from that being, and so an aspect of it” (Crossley-Holland 1976: 50). Following this logic, sensory interaction with a mantra is interaction with the divine. Similarly, the mantras written all over the landscape help to cloak it in the presence of the divine.

This ability of the mantra to reshape the landscape is exemplified further in the prayer flags hung from high surfaces all across Tibetan Buddhist communities.

My friend Sherab explained to me that the Buddhist prayer flags are hung in the windiest places, because every time they flap they send the mantra written on them out into the world. As discussed earlier, mantras have the ability to reshape people and places through sensory contact. Imagine a line of flags, whipping back and forth. With each movement, waves of vibrations are carried across the landscape, spreading the mantra written on their threads as far as the wind will carry it. These waves of vibrations create sounds, too [sound clip of flags in the wind]. In his study of voice, place, and identity in Kenya, Andrew Eisenberg writes about the territoriality of sound, the ways that sounds can create social space based on how far they travel and who interacts with them. He argues that “sonic practices territorialize by virtue of combining physical vibration with bodily sensation and culturally conditioned meanings” (2015: 199). As the prayer flags send out their vibrations in the wind, they shape the landscape around them into a sacred space, from which liberation becomes more accessible.

The physical vibrations emanating from flags reminds us how religious icons and texts have the ability to transform “the ordinary, coarse world into an extraordinary realm of spiritual wisdom and compassion” (Farkas 2009: 30). From the way mandalas are created in buildings to represent the universe, to the dying practice of Sky Burials, to the sounds of prayer flags in the wind, we see how “territorial and spatial dimensions are intrinsically linked to the practice of religion” (Terrone 2014: 463).This is not religion that adheres primarily to specific doctrines, but is rather a form of religion incorporated into daily life through smaller practices and reflections of the landscape.

The Smell of the Cows

Throughout my time in Kagbeni, I heard over and over about people who had left the town and came back years later, or who now live elsewhere and visit as often as possible. I was surprised by the number of visitors I met in the month I was living there, and how positively they reminisced about returning home. When I asked people if they would want to return and live in Kagbeni instead of only visiting, they said things like “that would be nice” or “oh yes, I wish,” but in a way that told me they never would. I became curious about why many people return to visit, but so few come back for good.

This question could be answered in part by looking at the factors limiting opportunities in Mustang, which is one of the main reasons people leave. Not surprisingly, the restriction of the region from the 1960s onwards played a large role in Mustang’s ability to grow and change over time. Manjushree Thapa explains this dynamic:

Restriction had not kept Upper Mustang beyond the reach of the modern world. Rather, it had forced people out. No new sources of income had entered the area, nor had traditional occupations found means to grow. The history-book pattern — of farming in the spring, animal husbandry in the summer, and trading in the winter — had remained the same for centuries; it had stagnated (Thapa 2008: 80).

This restriction was accentuated by Chinese policies to the North as well. Following 1959 and the invasion of Tibet, “Chinese authorities had clamped down on the practice of grazing of Nepali animals on Tibetan grassland” (Thapa 2008: 51). This means that there was less dung that could be used for fuel, less animal meat, and less revenue. Migratory grazing was no longer an option in the way it once was. This policy of restriction is promoted as something that protects the culture and keeps the area as a living museum, but has evidently harmed Mustang greatly after decades of not providing support to the region. Without opportunities beyond agriculture and tourism, people who have the means to leave do, and only some return.

It quickly became clear to me upon arriving in Mustang that the locals are heavily impacted by the land. We have already seen this to some extent in the way that buildings are made, and the relationships between religion and landscape. This area north of the Himalayas is classified as high-altitude desert, with low-lying trees sparsely spread along the gorge. The endangered blue sheep roam the hillsides above 3500 meters, and Himalayan vultures occasionally fly overhead. Wind and water have shaped the Kali Gandaki gorge (which was once on the bottom of the ocean floor), but they have also shaped the people who live within its walls.

Towards the end of my stay in Kagbeni, I had the opportunity to meet three siblings who are originally from the town but now live in New York City. They were a few years older than me. The sister had moved to the United States for school, and was working on a master’s degree. When I met the siblings, they were visiting their mother and grandmother, and said that they would be in Mustang for two months before returning to the USA. They missed this place, they told me, and needed to get a break from the hectic lifestyle of the city. I began to tell them about my project, explaining that the idea started because I was curious about the relationship with people and place. The sister nodded and said “the people here, they really respect the land, you know? Not like in New York.” It is clear that, in Kagbeni, much more attention is given to what comes from the land, and how people interact with the land on a daily basis. In New York City, the sister argued, this connection, this respect, was lost. This sentiment was communicated to me by other people I met, like Kunga, who took such pride in the fresh food of Kagbeni, and it made the cultural use of the land another site of differentiation for the people who spoke about Mustang. Just as with the political and geographic boundaries placed on Upper Mustang, statements like the sister’s once again distance Mustang from other places, this time focusing on the people rather than the land. This is done by both outsiders as well as locals.

Another friend – Mama – told me a similar story about another Loba who lived in New York for many years before returning to Kagbeni: “he just gave up everything and moved back here to Kagbeni… he just loved this place, man. The smell of the cows.” As someone who lives in Kathmandu but returns to his home in Tiri (across the river from Kagbeni) a few times a year, Mama showed a sense of disbelief at the man in his story. He too had moved away, made a new life and started a family in the city. One of his brothers was living in New York, studying to be a photographer. And yet, they were both pulled back to Kagbeni and Tiri, just like the three siblings earlier. Mama may have laughed about the smells of the livestock, but even he admitted that he would like to visit more than he does.

At the monastery, the monks provide another example of a lasting commitment to the Kagbeni community. The khenpo, who also happens to be Mama’s brother, was originally from Tiri and came back to head the monastery after receiving a higher level of monastic education in India. In addition, one of the younger monks, Dorje, was saw his role at the monastery as a service to his community. In his 20s, Dorje left Tiri for a few years to go to school and live in Kathmandu, but has since returned in order to give back to Kagbeni as the middle son of his family. Dorje explained that it is common for people from the surrounding towns to serve at the monastery for a few years, without the expectation that they would remain a monk. In his case, Dorje spent one year at the monastery before returning to Kathmandu for a year, and is now finishing his time at Kag Chode in a two-year segment. He prefers living in Kathmandu, like many other men around his age that I talked to, but also recognizes that it is nice to be out of the city and back where his family is from. When asked if he would continue to be a monk when his three years of service were over, Dorje admitted that he had not yet decided.

One of my older students showed this commitment in a different way. In order to be ordained at a higher level, monks in the Sakya sect must receive further schooling in India. Of the 64 students at Kag Chode, it is likely that only a few will follow this path. As they get older, students often decide to disrobe and reenter lay society. Since the school provides both a monastic and secular education, many families send their children there for the free education and housing, knowing that their children will be able to succeed with the education whether or not they remain as monks. When I talked to one student about his plans following his graduation, he told me that he wants to be ordained at a higher level, which means going to India. After receiving this further education, his goal is to return to Mustang and help run the gompa and teach younger students.

People leave Mustang for school, better jobs, seasonal work, or other opportunities. They come back for different seasonal work, festivals, or to visit family. Because the winters are harsh in Mustang, many people leave for the season. While a few older community members and children stay behind to keep the town running in the coldest months, the majority of people find work or live elsewhere. The entire monastic school, for instance, picks up and moves to Pokhara for a few months. This seasonal migration is by no means a new phenomenon, and shows that even when Mustang was restricted to foreigners, people have always come and gone with some frequency. Their claim of being Loba, however, remains with them. People living in Kathmandu identify where they are from or what their ethnic background is when they talk about their life in the city, and they also label others in this way. For example, one trekking guide mentioned that he has “a lot of Manangi friends.” Manang is the region to the east of Mustang, and even if his friends live predominantly in Kathmandu, the guide still identifies them as being from Manang. In the same way, people often refer to a place as “my village,” even when they have lived in Kathmandu for most of their lives. Along the same lines, people who live in Kathmandu almost never say that they are form Kathmandu.

Claiming the identity of the village or region your family is from is common throughout Nepal, and is in many ways related to the caste system and Hinduization in the Panchayat era. This is also in part due to the wide diversity of ethnic groups and languages in Nepal, and the original formation of the country in the 18th century as a unified kingdom made up of many smaller, previously distinct groups. While people in Mustang are definitively Nepali, they have a deep connection to their homeland. As with the gompa donor now living in Hong Kong, many people want to maintain a connection to the region and support it when they can. In Mustang Bhot in Fragments, Manjushree Thapa tells the story of one man who lived in Kathmandu many years before returning to Mustang, hoping to improve the area after growing accustomed to the ways of the city. When asked why he wanted to come back and work on developing the area, he responded “this is home. If we don’t improve it, who will?” (Thapa 2008: 50). This statement not only shows the deep connection that Loba have to their communities, it also implies that other people cannot be counted on to improve life there. After a history of being let down by the Nepali government and other development projects, it makes sense that the community would take it into their own hands to build the road north to Tibet, to spur the possibility of more opportunities.

Team Tashi Delek

Up until this point, there have been occasional points of friction between Nepali and Tibetan and Loba identities. In ethnicity, religion, culture, and language, people of Mustang appear to be closer to Tibet than Nepal. This perception is held by most Nepali citizens, both from Mustang and from elsewhere. At the same time, these borderland communities are still Nepali, learning the official language and singing the national anthem each day in school. One day in class at Kag Chode, I was working with the students to practice grouping words that use the same vowel sounds. I created teams, splitting the class in half, and asked what they wanted their team names to be.

“Team Tashi Delek!”

“Team Namaste!”

The students broke into laughter, pleased with the names they had chosen.

I bring up this moment with the students (this class was ages 10 through 12) because it points to a divide in how Loba people perceive themselves in relation to Nepal. Tashi delek and namaste are Tibetan and Nepali words respectively, and are both used as greetings. The local language in Mustang is Loke, which is closely related to Tibetan. As a result, tashi delek is almost always what you hear being tossed around as you walk through the streets. Namaste is reserved for foreigners and other Nepalis. While children are taught both Nepali and English in school (in addition to Tibetan language at monastic schools), people primarily still speak in Loke in Kagbeni, rarely switching into Nepali or English unless there is another person around who speaks one of those languages. English, Nepali, and Tibetan music mingle in the streets of Kagbeni, as people play music to accompany the harvest, household chores, or evening downtime. Each language carries a different cadence, mediating spoken interactions between locals and others passing through.

This divide is in part due to the Nepali government’s history of aid (or lack of it) in Mustang, but is also deeply rooted in the cultural identity of Mustang. The heart of this issue comes from the distance that is felt between what it means to be Nepali and what it means to be Tibetan, and finding a place somewhere in between. While giving myself and a Nepali business group from Kathmandu a tour of Kagbeni, Mama explained

Upper Mustang, Lower Mustang, we want to be called Tibetan, but we are not Tibetan. Tibetans are migratory people you know? But because I was born here I can say that I’m Tibetan. Historically we wandered around place to place with the yaks looking for grass.

This points to the divide between how Loba people see themselves and how other Tibetan and Nepali groups see them. My friend explained that even though he is not ‘Tibetan,’ he still identifies as being Tibetan, and does so proudly. Similar sentiments were expressed to me by other people in Kagbeni. Throughout Kagbeni, and Upper Mustang to the north, people align themselves more closely with Tibetan culture than Nepali, while still maintaining their Nepali identity as well.

The royal family of Mustang provides a good example of the complicated relationship between Nepali and Tibetan identities. The family is said to be descended from Tibetan kings, yet today holds the surname Bista. This once again traces to the Rana regime and the following Panchayat era, in which “of necessity, the [Loba] colonized themselves” (Thapa 2008: 124). The name Bista comes from high-caste Hindu families originally, and was thus appropriated in order to increase the family’s authority and recognition in the eyes of the Nepali government (Thapa 2008). Other Loba took on surnames in a similar way, often appropriating names of ethnic groups to the south of Mustang. While the Bistas are no longer recognized by the Nepali government today, they still hold social power in the region. One trekking guide who was originally from Lo Manthang told me that part of the reason the local people still respect and listen to the royal family is because “it is past karma,” so the people of Mustang just know to follow them. Whatever the reason, it became clear to me that the Loba put more trust and respect in the royal family of Mustang than the Nepali government.

Beyond language, there are other clear physical markers which point to the Loba being more in line with Tibetan culture. The clothing, buildings, and even the landscape of Upper Mustang all mirror that which is found in Tibet. While my friends from other regions of Nepal frequently spoke of wanting to travel to other regions of the country, the Loba I know in Kagbeni only ever spoke of wishing to visit Tibet. This is not purely for religious reasons, though going to pilgrimage sites such as Manasarovar lake certainly contributes to this desire.

This closeness to Tibetan culture was further emphasized after 1959, when Mustang became a one of many settlement areas for Tibetan refugees “due to its close proximity to Tibetan territory, strong kinship and monastic relations with Tibetan populations and social–physical landscape congruent to the Tibetan Plateau” (Murton 2017: 538). Here, it is clear that the association between Mustang and Tibet goes past simply proximity or culture. In popular discourse, however, Mustang is still essentialized as being as close as you can get to “authentic” Tibetan culture as it was before 1959. This perception is damaging for many reasons, and will be explored more in relation to tourism.

Reshaping Mustang

Mustang, Nepal has been shaped both internally and externally by religion and its relationship to politics and culture. Buddhist and Bon structures have physically reshaped the landscape, linking to mythology that maps onto it. These recreations of the land go back hundreds of years, to when Guru Rinpoche first came through the Kali Gandaki in the 8th century. Bon influences on the land go back even further. The mingling of Buddhism, Bon, and Hinduism has taken on ulterior motives in the last century, however. Due to the governmental policies and lack of infrastructure in the region, Loba were pushed to either assimilate and become more recognizably “Nepali” (meaning more Hindu), or leave for better opportunities elsewhere. The relationship with Tibet to the north was largely halted as well, with only a trade fair in the summer remaining.

Turning towards the tourism industry, the region is frequently characterized as a stronghold of Tibetan culture and religion, preserved by the restriction of the region. Government policies, tourism agencies, and even museums point to Mustang as being a special place in Nepal because of the presence of Tibetan Buddhism and Bon in its valleys. Kagbeni, on the border between Upper and Lower Mustang, shows us that this popular essentialization of Loba people as purely religious in many ways misinterprets the role of religion in daily life. Yes, signals of Buddhism and Bon and Hinduism abound in the small town, and some people do sit outside in the sun with prayer wheels spinning in their hands, but this misses the complexity of the Kagbeni reality. Lives in Kagbeni are complicated and reshaped constantly by the government, religions, and tourists intersecting within its space. In the following chapter, I turn to look more closely at the impacts of tourism in and scholarship about Kagbeni and Upper Mustang.