History, Colonization, and Development

A Brief Political History

Imagined Physical Boundaries

The Internal Colonization of Nepal

Road F042

Stopping at the Convergence of Two Rivers

Overlapping Boundaries

Each morning in Kagbeni begins with the sounds of water and wind; fitting, since these are the main elements people mention when they talk about Mustang. Animals are herded into the hills early every morning, and sounds of construction begin to ring within the town and from the road above. As the day goes on the wind picks up, reaching its height in the early afternoon. Kunga, who owns one of the hotels in Kagbeni, tries his best not to go outside between noon and 5:00 to avoid the gusts that bring dust into your eyes and mouth. Messengers call out the local news, and people working in the fields play music to accompany them in the harvest. Animal bells return as the goats are brought back from grazing in the late afternoon. Herders whistle at the cows, goats, and dzos to keep them in line. Around dusk the construction noises ebb away, and people return to their homes for an evening spent talking over dal bhat and tea. Crickets chirp in the grass outside, slowly building to become the dominant sound, interspersed with dogs barking down the street. These are the sounds and rhythms of everyday life in Kagbeni. People wake up with the sun, go to work, come home, and spend time with family and friends, as the wind and water shape the gorge around the town.

The wind and water are not the only factors exerting force on Kagbeni, however. Sitting north of the Himalayas, the Mustang region is physically separated from the rest of Nepal. A single road leads to the region, and even this is closed for much of the year due to water levels and landslides along the Kali Gandaki gorge. Even when the road is open, there are often lengthy delays for construction, or road blocks where jeeps and busses must back up to let another pass by. This road was built only in the last 15 years, and connects India and China for ease of trade through Nepal. Trekking routes to Manang to the east and Dolpa to the west still exist, but are primarily used by adventure tourists and sporadic local groups on foot. Thus, road F042 is now the main mode of access the region. Occasionally helicopters bring government officials or high-end tourists directly to Lo Manthang, the capital in the northern reaches of Mustang, but most visitors must take a long bus ride or pay the higher fees for a small plane or jeep from Pokhara. This geographic isolation has impacted the region in many ways since the unification of Nepal in the 1700s, and has been accentuated by governmental policies towards the region.

In this chapter, I explain some of the ways in which political and geographic barriers have shaped how people see Mustang since the formation of Nepal under King Prithvi Narayan Shah. These factors help to solidify the idea that Mustang is somehow different from the rest of the country, and has been marked as such on maps. The physical and political boundaries surrounding Mustang play an important role in how the region is perceived by Nepali citizens and tourists alike. I then delve into a case study of the town of Kagbeni, which sits on the southern border of the “Forbidden Kingdom.” This closer look at Kagbeni allows us to examine the ways in which the physical and political boundaries are tied to religious and economic barriers in turn.

A Brief Political History

The Mustang, Nepal which exists today cannot be analyzed in a vacuum. Global frictions between Mustang, Nepal, China and India, NGOs, and the globe continuously reshape the lives of people living there in a constant give and take. Given its location on the northern border of Nepal, it is important to consider both the history of Nepal as a whole, as well as its interactions with Tibet and China. For the sake of clarity and time, I have attempted to present only the information which is most essential to understanding the context of Mustang today.

Buddhism moved through Nepal towards Tibet in the 8th Century by way of Guru Padmasambhava (often called Guru Rinpoche). Bon, a folk religion with a large focus on nature and deities in the landscape, was already engrained in Tibetan communities. Over time, the Buddhism brought by Padmasambhava merged with Tantrism from India and Bon from Tibet, creating the distinct form of esoteric Buddhism that we know today as Vajrayana (or Tibetan) Buddhism (Crossley-Holland 1976: 51). As an ethnically Tibetan group directly in the path of Padmasambhava’s travels, the mixture of these religions is still evident in Loba communities of Mustang today. While both Buddhist and Bon practices are still present, Buddhism, especially the Sakya sect, is dominant in most of Mustang’s communities.

From a political standpoint, Mustang – the upper region in particular – has had a skewed relationship to Kathmandu and the central government since it joined Nepal. The region was part of the Tibetan kingdom Gungthang until the 1380’s. After that, the Kingdom of Lo (which now consists of the area known as Upper Mustang) stretched as far south as Kagbeni, with the walled city of Lo Manthang as its capital (Thapa 2008: 122). While its royal family is no longer officially recognized, the boundaries of Upper Mustang today follow the old borders of the Kingdom of Lo.

Prithvi Narayan Shah became the first king of Nepal in 1768, expanding the Gorkha kingdom to encompass the area that is approximately the boundary of Nepal today. Previously, the region had been comprised of many smaller kingdoms with their own royal lineages. Prithvi Narayan Shah expanded his empire by force, defeating the kingdoms surrounding Gorkha in the central hills (Thapa 2008). This dynamic is apparent in the language dynamics of Nepal in which Nepali is the official language and was the language of Gorkha originally. When the Shah rule over the new Kingdom of Nepal was being cemented, the Kingdom of Mustang remained untouched, seated north of the Himalayas. As one trekking guide explained to me over dinner, King Prithvi Narayan Shah struck a deal with the king of Mustang, not wanting to invade the region. The two kings agreed that the Shahs would not take over the Kingdom of Mustang by force, and in turn the Kingdom of Mustang officially joined Nepal in 1789 (Murton: 2017). This deal remained intact with the two kings ruling “like brothers” until the end of the Nepali monarchy in 2008, as the trekking guide explained.

The Shah dynasty remained until the middle of the 19th century when it was overthrown by the Rana family, which instated itself as the ruling hereditary Prime Minister. The Shahs remained kings, but the Prime Ministers essentially held all governing power. The Rana dictatorship lasted just over 100 years, from 1846 until 1951 (Gellner 1997). Many Nepalis consider this the most corrupt time in their government’s history. During the Shah dynasty the royal family of Mustang retained some authority over Lo, the capital of the region, though the Nepali central government regulated revenue. Mustang, and especially the village Kagbeni, had long held a strategic place on the trade route between India and Tibet. Under the Rana dictatorship, however, the communities in Mustang became increasingly impoverished and neglected by the central government.

In 1862 “control over the flourishing salt trade along the Kali Gandaki was vested in the office of the customs collector in Thak,” the region to the south (Thapa 2008: 122). This trend of moving power out of Mustang continued through 1950, when the King of Mustang lost more power “with the re-emergence of the Shah dynasty and the democratisation that swept Nepal” (Thapa 2008: 122). Soon after, between 1951 and 1990, the central government became what was called the Partyless Panchayat Democracy. Elections were held to place people in the National Assembly, which was meant to better represent Nepal. These changes in the central government were each accompanied by changing policies toward Mustang, always keeping the region to the periphery.

In the 1960s, Upper Mustang was officially closed to foreigners. This closure was largely due to the political tensions with Tibet and China at the time. In 1959, the tensions between the People’s Republic of China and the people of Tibet boiled over, causing a rebellion and tightened Chinese control over the region. The Dalai Lama fled to India, and around 80,000 Tibetans followed close behind. Subsequent waves of people have since left, moving to refugee settlements or creating a life elsewhere. Today, there are members of the Tibetan diaspora living around the globe in a wide variety of circumstances – including many in refugee settlements in Nepal (one of which is in Mustang).

As a response to the Chinese control of Tibet, a militant resistance group called the Khampas formed, with their activity centered in and around Mustang. In 1960, a military base was established near Jomsom, a town a few miles south of Kagbeni and the border of the restricted area. Aided by the U. S. Central Intelligence Agency, close to 6,000 Khampas fought Chinese forces across the border. Members of the resistance group were even brought to Colorado for training in order to improve their operations in Mustang. Eventually, “desperate to appease China but unable to control the Khampas, the Nepali government declared Mustang restricted, and censored news of guerrilla activities” (Thapa 2008: 123). The CIA eventually discontinued support for the Khampas in the early 1970s, when the United States officially recognized the People’s Republic of China. Around the same time, the central government opened the lower region of Mustang to tourism, and made plans to deliver services like schools, health posts, and improved infrastructure (Thapa 2008).

Due to the height of the Khampa activity, outsiders were not allowed into Mustang for nearly 30 years. In the time that the region was closed to outside travel, state services were hardly delivered. With the closing of the region, “livelihoods based on transborder pastoralism and trade were severely disrupted, resulting in the suspension of historical exchange patterns and curtailment of long-standing kinship practices between Mustang and Tibet” (Murton 2017: 538). This disruption is still felt today in the people who live in Mustang. On various occasions, the adults I met would mention that they missed being able to travel to Tibet as they had when they were younger.

1990 brought another shift in the central government of Nepal. This time, the Shahs were back in power under a Constitutional Monarchy. In 1992, nearly 30 years after Mustang was closed, the restrictions on the area were lifted. Mustang was integrated into the Annapurna Conservation Protected Area (ACAP) in the name of conservation, though Upper Mustang still requires an extra permit and a hefty fee in addition to the regular ACAP permit (Thapa 2008: 128). At first, only 200 tourists were allowed into the region each year, and they were required to be in organized groups with recognized companies (Thapa 2008: 129). Over time, the number of tourists in the region has increased to more than 4000 people in 2014. The flow of tourists to the region were also impacted by the People’s War, which began in 1996 and lasted until 2006. Mustang was not as involved in the war as other rural regions were to the south, but the dip in tourist activity between 1999 and 2006 reminds us that politics and tourism are linked on many scales.

The state Monarchy officially ended in 2008. No longer the “Last Hindu Kingdom,” Nepal became a “Federal Democratic Republic.” This title is somewhat of a joke among some of the Nepali people I spoke with, because it is unclear what the title actually means in the context of Nepal’s past governmental experiments. One friend from Kathmandu even asked me “do you know what that means, Abracadabra? If you do, let us know because we also do not know.” With Nepal’s shift to a Federal Democratic Republic, the monarchy of Mustang officially ended as well. Among Mustang’s communities, however, many people still recognize and respect the authority of the royal family even if the central government does not.

Imagined Physical Boundaries

Whenever I mentioned that I was going to be living in Mustang for a month, Nepali people from other parts of the country reacted in one of two ways. The first way was to be surprised and worried about the length of time I would be there alone, and to give me a warning the Mustang is very “windy” and “cold.” No matter how well my friends in Kathmandu and Pokhara knew Mustang, they knew about the strong winds. These conversations were usually punctuated with laughter, as if they could not believe that I would want to go to such a place that was so far from everything and where the weather was unappealing.

The other reaction that some of my acquaintances had when we talked about my trip to Mustang was a sort of awe-filled jealousy. Almost everyone, even those who had laughed about the wind, said that they would like to go to Mustang someday. Mustang is known for its distinct high-altitude desert, endangered animals, and the important pilgrimage site Muktinath, which sits just south of the border demarcating the restricted zone. Muktinath is one of a series of sites that people go to when family members die, and is primarily visited by Hindus from central and southern Nepal as well as from India. It considered by many a place everyone in Nepal should go at some point in their life. As a result, some of my friends had been to Mustang in order to visit Muktinath, but they did not know much else about the region. Whether they had been or not, it was clear that they understood Mustang to be a special place.

This view of Mustang as special in Nepal came out in many of my conversations with people who were from other regions of the country. This was made especially clear to me in my first few days in the country, when I was staying with two friends and their families. Both families used much of the same rhetoric when they talked about Mustang and how nice it was that I would be going there, always reiterating how windy it was, and how every Nepali person should go there at some point in their life. The younger generations added another element to these conversations, saying that the landscape was beautiful and good for hiking.

This perception of Mustang also extended to Nepalis no longer living in Nepal. The Nepali waiter in Burlington, Vermont called Mustang a “dream place,” saying that it is a place that everyone should go before they die. Rajan, a Nepali man now living in London, recommended that I go to the Jomsom area of Nepal because it was a “special” place. What surprised me about this was that he said it without my mentioning that I would be living in Mustang for a month.

In both of these reactions lies the idea that Mustang is different from the rest of Nepal. Not only is it colder and windier, the people and landscape are often described as being different from everywhere else in the country. It would be a mistake, however, to think of Mustang as the only place in Nepal that is “different,” since there is such a diversity of landscapes and people across the nation. Nepal has three distinct geographic areas (the Himalaya, the Hills, and the Terai), and over 120 ethnic groups and languages. Each valley has a distinct personality. Yet it remains true that this region north of the Himalayas has historically been set apart from the rest of the country for political reasons, accentuated by differences in culture, and in recent years the vocabulary of separation has been used to attract tourists as well. This divide has certainly made an impact on the perception of the region to outsiders, both in Nepal and abroad.

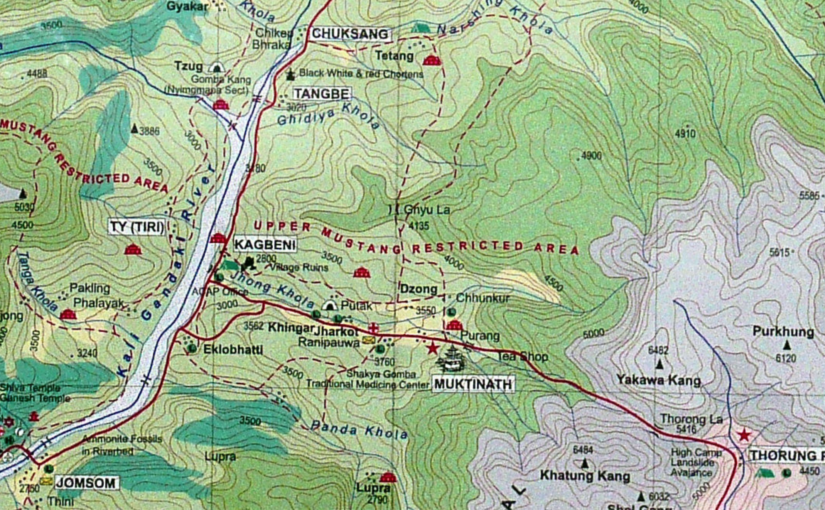

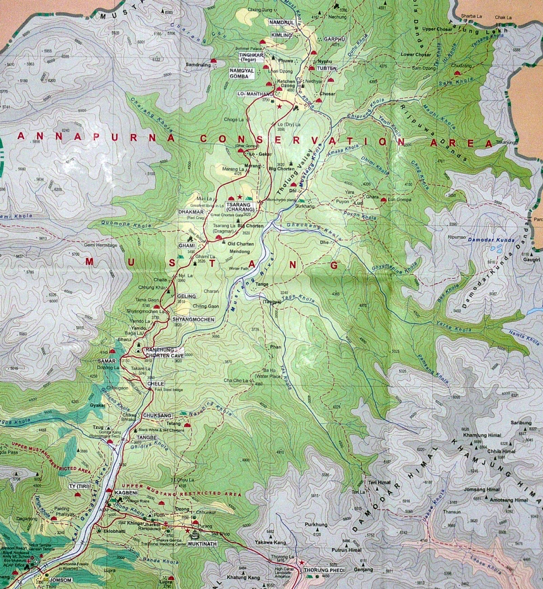

One factor contributing to this mental distancing of Mustang is the physical border of the area, and the permit required for foreigners. Most maps of the area represent Upper Mustang as separate from the rest of ACAP with a different color or by placing a line around the area. The map shown in Figures 5 and 7, for example, has the words “restricted area boundary” floating just north of Kagbeni. The extra permit needed to enter Upper Mustang in addition to the ACAP permit demarcates the area as different and somehow more special. Not only this, it applies a barrier between Mustang and the rest of Nepal, somewhere between physical and imagined. Looking at the landscape, there is no physical difference between one side of the border or the other, but a single sign marks where the line lays. This imagined physical boundary continues to reinforce the belief that Mustang is different in the minds of Nepalis and foreigners alike, even though Nepalis do not need to pay the same extra fee as foreigners to enter the area. Most Nepali citizens do not go north of Muktinath in any case, staying below the border of the restricted area. With this imagined boundary, Mustang becomes an idea and an ideal in addition to a physical reality.

The Internal Colonization of Nepal

Figure 8: “Ethnographic Map.” Harka’s Maps. Nepali Times. Accessed March 25, 2019.

Today, there are 103 officially recognized ethnic groups and 93 officially recognized languages in Nepal (Turin 2007). This diversity is celebrated by foreigners who applaud Nepal for having religious tolerance and diverse communities that coexist peacefully. It can be seen in the new Nepali national anthem that highlights the landscapes and communities present, and in many current projects that aim to show the diversity of Nepal while building pride in the Nepali identity.

Modernist attitudes obsessed with defining people as a specific caste or ethnicity have resulted in religions being defined the same way ethnic groups or nations are: by building boundaries between them. In Nepal, this means that religious practices or beliefs were designated by their relationship to Hinduism, and tied to caste and ethnicity. This movement to define people as different from others in Nepal can be seen beginning under the Rana dictatorship as a result of internal colonialization, in which the Rana regime designated its own status and defined social units (Gellner 2005). Thus, minority groups were labeled as “ethnicities,” while the majority or ruling group continued to be normalized.

This labeling of smaller distinct groupings in combination with acknowledgement of their differing religious practices has resulted in a gradual “Hinduization” over time (Gellner 1997). While the norm is set by the ruling class (or caste), each ethnic group played into this Hinduization in order to make themselves be seen as more legitimately Nepali. As we saw above, the Loba of Mustang were pushed to the side by the Rana regime and the Panchayat system following it, along with other groups that did not appear to be “Nepali” enough. Out of this ongoing process of Hinduization has come the desire for those who are marginalized in some way to express themselves in a way which is both true to their tradition and acceptable in the larger Hindu nation.

When the Panchayat system of government arose in the 1950s, it promoted a strongly Hindu vision of what it means to be Nepali. Under the Hindu state, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, and folk religions were each seen as branches of Hinduism. In this hierarchy, they were thus accepted as lesser forms of the dominating belief system (Gellner 2005). As a result, the 20% of the population that does not identify as Hindu – whether they are Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, or otherwise – had to shift their own outward identities in order to better fit with the national vision. For example, the Loba were seen as not legitimately “Nepali,” and did not fit into the Hindu caste system (along with many other groups in the mountains). In order to increase their authority, many started using names of other ethnic groups which were considered more legitimate, such as Gurung. The royal family of Mustang took the name Bista, which is associated with high-caste Hindu groups to the south. While the obvious marker of difference here is that the mountain communities are primarily Buddhist, ethnicity stands in for religion in this context; because religion and ethnicity have come to be closely linked in Nepal, taking a name of a Hindu ethnic group means taking a more Hindu name.

With the end of the monarchy, Nepal is no longer a Hindu Kingdom. Under a secular government Hinduism is still the preferred religion, and people who assimilate with Hinduism more are seen as more desirable. The Hindu state and unified Nepali identity promoted first by the Ranas and later by the Panchayat system of government led to an internal colonization of the castes otherwise ignored by the central government. As Manjushree Thapa observed in her travels to Mustang, the Loba “had discovered that identifying themselves as members of a legitimately Nepali ethnic group facilitated dealings with the government” (Thapa 2008: 64). With a name like Gurung or Bista, Loba people gained visibility in the Nepali system.

This internal colonization is important in the discourse surrounding Mustang because it is an expression of the separation of Mustang from the rest of Nepal. For example, people who aren’t from Mustang consistently bring up how different it is, but Loba who live there almost never mention how Mustang has been separated, with the exception of their connection to their Tibetan heritage. People who have never been to Mustang know very little about the people who live there, and mostly know the region for the temple of Muktinath. In her travelogue of Mustang, Journalist Manjushree Thapa said that the region held little of what she considered ‘Nepali.’ For her, this vision of Nepal “was exemplified… by the hillside villages and lush terraced fields of the Himalayan area… the people I saw [in Mustang] were just as far removed from mainstream Nepal as I was” (Thapa 2008: 25). Her final comment alludes to her upbringing, as Thapa is Nepali by birth, but grew up largely in the United States.

Road F042

When traveling through Mustang, it is impossible to ignore the impacts of the road that runs along the Kali Gandaki. The dirt road winds along the walls of the gorge, occasionally passing back and forth through the river itself. Construction crews work by day to make the existing road wider and to build new bridges across the river. Man-made rock walls diverge the river in places where the road dips low to help protect it from erosion when the path of the river shifts. The sounds of large machinery carries through the gorge, reaching the ears of nearby towns.

Although the road has now been in place for over 10 years, it is still closed for months of the year due to water levels in Upper Mustang. Landslides are common in the spring and summer, and even when the road is open, there can be hours of delays due to construction and improvements. When I took the bus from Jomsom to Pokhara in early July, for instance, we were stopped for hours at multiple places where landslides were being cleared, or where improvements to the road were being made, or where lines of cars needed to reverse so that others could pass. A group of us in the back of the bus calculated that we traveled an average of six miles per hour over 16 hours (though that does include time for eating lunch and dinner along the way).

Mustang has historically been an important stop along the salt trade moving between India and China. As Galen Murton states, “the former Kingdom of Mustang has long bridged the ecological, cultural, and economic worlds of both Nepal and China” (2017: 536). With the restriction of the region in the 1960s, however, Mustang received very little attention from the Nepali government for many years, and trade was constrained. Under each of Nepal’s governments, the region has long been perceived as a “marginal borderland,” not fully a part of Nepal (537).

As a result, the building of a road through the region was in no way a priority for the Nepali government. Residents of Mustang have been appealing to the central government for this road since the mid-twentieth century. This request came from a desire for connections between their communities and the rest of the country, and to facilitate improvements in commerce, education, medicine, and opportunities (Thapa 2008). A road was promised, but never delivered by the government. In the end, the Loba community did the majority of the work, taking it into their own hands to construct the first road from Lo Manthang to the Chinese border in the early 2000s (Murton 2017: 538). Notice that the first road built in the region was not to connect Mustang to the rest of Nepal, but to Tibet in the north.

The building of road F042 through Mustang has produced three interdependent outcomes, according to Murton:

- new consumer subjectivities supported by transborder trade;

- new mobilities that reinscribe long-standing social hierarchies;

- new political economies that make space for the Nepali state to take shape (537)

People were eager for the road, hoping it would bring new economic opportunities with the shift towards a tourism-based economy. Although the community asked for the road, the infrastructure accentuates old patterns of social division.For those who have money, roads are a faster means of transportation, and travel by vehicle comes easily. For those without cash, however, the roads make mobility much more difficult as they must rely on unreliable public transportation (541). As the economy of Mustang has shifted from barter-based to cash-based, the road has played a major role in limiting new mobilities. In addition, many people with homes near the road complain that the only thing it brings is dust, since tourists now travel more quickly and stop for tea less frequently. Even though the road opens access to the region, bringing in goods and tourists, it also controls the movements of those who live in Upper Mustang, especially the people without a vehicle. The road is thus a location of friction. It increases opportunity for some while limiting options for others, conveying the unequal power dynamics between Loba communities and the world driving or trekking through them.

Friction is not just about less powerful communities at the mercy of global forces. It enables and excludes (Tsing 2005: 6), but it also allows space for the agency of these communities. Remember, the community in Mustang took charge of building the first segment of the road towards Tibet by themselves. Another place this agency can be seen is in the pathways weaving across the region. All along the new road, there are smaller trails and shortcuts used by the residents of Mustang. Whenever possible, people walking from one town to the next choose to take these trails rather than walk on the wider road. This does not negate the impacts of the road, but it does complicate the idea that Mustang must accommodate global forces entirely.

Stopping at the Convergence of Two Rivers

Until this point, I have been discussing the factors affecting Mustang as a region, especially the restricted Upper Mustang. Now I turn towards Kagbeni, the final town before the border of the restricted area. On the southern border of restricted Upper Mustang, Kagbeni is the last town that foreigners can travel to without paying a hefty daily permit fee. Approximately 300 people live there, surrounded by terraced fields growing barley and buckwheat. The town is positioned at a narrow part of the Kali Gandaki gorge, the deepest gorge in the world, and the Kali Gandaki and Dzar-Dzong rivers flow together at its center. One road branches to the east, following the valley to Muktinath, while another stretches north into Upper Mustang. Tiri village can be seen across the river, about a half hour’s walk north. The Annapurna mountain range is visible to the south, and Dhaulagiri lays visible beyond the next bend. This narrow part of the gorge has historically been a stopping point for trade moving back and forth between India and China, allowing Kagbeni the strategic position to collect taxes on the goods moving through. At the convergence of two rivers, the town gets its name. Kag, a “stopping point,” and beni, where two rivers come together.

Manjushree Thapa chronicles her travel through Mustang in her monograph Mustang Bhot in Fragments, describing Kagbeni as “the southernmost of the Bhotia villages of Mustang; [there were] fixtures of Tibetan culture in the houses and chörtens, and in the gomba that had been closed to tourists since a theft a few years back” (Thapa 2008: 26). The Bhot, or Tibetan highland, begins at Kagbeni and stretches north (29). Since Thapa’s travels in the early 2000s, the Kag Chode monastery (the gompa she refers to) has since been reopened to tourists and made into a monastic school for boys from Mustang and Dolpa. Today, 64 students between the ages of 5 and 18 attend school there. Five other monks also live there, overseeing the grounds keeping, business needs, and education. In addition to taking classes in the dharma (teachings of the Buddha) and Tibetan, the students also receive a secular education in math, science, English, and Nepali. This is a common feature in monastic schools in Nepal today, as it makes it easier for students to disrobe and reenter lay life successfully as an adult after their schooling. This is also representative of the intersection between Tibetan and Nepali culture, one of the many overlapping intersections overlaid on the town.

Kagbeni is divided down the center, with the old section on a peninsula between the two rivers, ending with the Kag Chode monastery right at its point. These older houses are all connected, with narrow streets weaving their way between the mud walls and under low tunnels. At the northernmost tip of the town sits “café Applebee’s,” across from the government checkpoint for people continuing north. The newer buildings reside over a bridge on the other side of the smaller river, extending towards Muktinath to the east. Brightly painted hotels and tourist shops line the streets, sporting names like “Shangri-La Inn,” “Nilgiri View,” or “Hotel Dragon,” “Yac Donalds,” or “Hotel Show Boat.” These names are representative of the discourse used in the tourism industry in Nepal. Names are choesn which refer to popular western brands, or which play up the mystical or exotic nature of the destination. In addition, the bright bubblegum-pink and sky blue colors of some of the hotels and restaurants makes them stand out among the older earthen buildings.

When looking at the houses in Kagbeni and Upper Mustang, the older ones all have piles of firewood stacked around the edges of their roofs. Today this is mostly for show, but the piles themselves have been sitting on the houses for around fifty years, once used to provide heat in the winter months. One day I asked a friend why they don’t use the wood anymore and he just turned to me and said “deforestation, man” and laughed. This friend, Mama, was constantly joking with me and the people he traveled with. I encountered him with his group for the first time as they were passing through Kagbeni on a business trip, scouting for possible locations to build renewable energy projects. The group returned a few days later, inviting me to tag along as they visited Tiri and other potential sites across the river. From his joke about deforestation, Mama went on to add that there are other methods of heating now, including the solar heating of water that is used in most of the hotels. While the people of Upper Mustang have moved on to newer heating technologies, the remnants of the firewood on their homes points to a connection to and full use of the land around them.

The colors of the older buildings, too, point to a respect and reflections of the land surrounding Kagbeni. While the new hotels are built with concrete shipped up from Pokhara, older buildings were made from mud and clay and wood. Even the Kag Chode monastery, which was built in the 1400s, is stained red with natural dye. The khenpo of the gompa complained to me that the paint on the new dorm buildings for the students is much too bright. While they are still painted in the yellows and reds and browns of the older buildings, they are jarring to look at.

This summer, Kag Chode monastery consecrated a new building. In preparation for the ceremony, construction work was underway every day to finish the new building and bridge leading across the river to it (pictured in Figure 2). As a result, construction sounds often mingled with the normal sounds of the gompa. Children screaming and running around during their breaks between class, the ringing of the meal-time bell and the class-time bell, and the low rumble of locals repeating Om mani padme hum as they walked along the prayer walls met ever-present rushing wind and water, interspersed with music and car horns. The sounds of the gompa are just like the rest of Kagbeni, just with the addition of occasional pujas and instruments.

A large portion of the money for the new gompa came from a man who is originally from Kagbeni and now lives in Hong Kong. In talking to people about moving away from Kagbeni, it became clear that this maintained connection to the town is common, and that most people who leave continue to support the community from abroad, fitting in with wider trends of emigration and sending back remittances throughout Nepal.

The consecration ceremony involved three days of ceremonies, performances, and celebration, and people came from all over Mustang to attend. Because of my position as a teacher at the school, I was asked to help edit the welcome speech which would be given by a student on the first day of the ceremonies. Reading the speech gave me a window into how people in Kagbeni view themselves, and the assumptions that other Nepali people have about them. After welcoming everyone multiple times, praising the guests (including the royal family of Mustang and the head of the Sakya sect) for their goodness, and saying how special this moment is, the speech went on to list the benefits of the gompa to the community. The support for the gompa in Kagbeni has not only helped it and the monks succeed in Kagbeni, it has helped them thrive. This is contrary to the “poor opinions” of others outside Mustang, which see the region as purely a place that is remote, resource poor, and a bad place to live. The speech then ends with another round of thanks. These comments about outsiders’ perceptions of living in Mustang show that the locals do not necessarily agree with the stereotypes of the region, and are proud to live there. While they may say the same things about themselves, they resist these labels from outsiders. This pride can also be seen in the way people talk about the food and other local products.

Due to Mustang’s inaccessible nature, the food that people eat becomes a point of pride, and another representation of the full use and respect of the land. The geographic barrier of the Himalayas around Upper Mustang means that almost all of the food eaten in the region is grown locally. Kagbeni is especially known for having good quality produce, and demand from other regions of Nepal is beginning to overtake the supply. Some non-perishable food items are shipped in, especially snacks, but the meat and produce consumed in the area is almost entirely proudly local. An exception to this is the yak meat that is served in Kagbeni, since the elevation is too low for yaks to live healthily. According to Mama’s family, yak meat in Kagbeni comes either from Tibet to the north or Dolpa to the west. Gardens are squished between the houses and animal pens and terraced fields, constructed away from the streets. Kunga remarked to me that the freshness and organic nature of the food was one of the reasons he enjoys living in Kagbeni. “I have a house in Kathmandu too, you know, but I like to live here. It makes me feel more healthy.” This sentiment was shared by many of the people I talked to who had the option of leaving Kagbeni. If they did leave for school or work or other opportunities elsewhere, Kagbeni was always regarded as a place to return to that would make them feel healthier.

Sonically, Kagbeni also remains much healthier than Kathmandu. Although the town has recently been overcome with jeeps and busses trundling through, most days remain quiet for long stretches of time. A donkey braying is often the loudest sound in the immediate area, though noises from the construction of the road echo around the walls of the gorge. Kathmandu, in contrast, is filled with sound all the time. Dogs barking, bells ringing, and music playing weave into the fabric of daily life. The main sounds are no different, it seems. Except, there is no strong afternoon wind, no stream bubbling through the streets. Sounds of Kathmandu are more chaotic, as they fight for space and listeners. Of the people who could choose to live in Kathmandu or Kagbeni, the relative quietness of Kagbeni contributed to their choice to stay.

Overlapping Boundaries

As explored above, Mustang has historically been distanced from the rest of Nepal politically, economically, and culturally. The people of Upper Mustang are ethnically Tibetan, and tend to speak their local dialect (Loke) rather than the official language of Nepali. The economy rides on agriculture and tourism which plays up how different the region is from other parts of Nepal. In addition, the central government has given very little aid to the area in the past, and has generally neglected the region’s requests. On the other hand, the government still promotes a unified Nepali identity, which must find a place beside the strong Tibetan identity that many people in Mustang recognize in themselves.

The political and geographic barriers around Mustang are not the only forces at work in shaping daily life. The sound composition at the start of this chapter highlighted construction and natural noises, providing an introduction to Kagbeni as a recognized by someone coming to the region with the lens of a government official. This selective listening neglects the ways people in Kagbeni shape themselves, and paints them as a community pushed around by more powerful entities. Moving forward, a focus on the religious and cultural life of Kagbeni can show us how the landscape is reshaped by the people who inhabit it. Rather than conforming to government initiatives like the building of the road and moves towards Hinduization, people in Kagbeni have agency in how they construct and interact with the land around them.