Dining Halls

The construction of a sonic environment in a UVM dining hall is hugely influenced by the perceptual concepts of the active process of the ear, the sonic aspects that make up a soundscape, perception of a recording versus live perception, and open versus closed ears. These complex ideas can be investigated through analysis and application of the many given course readings.

An interesting difference to be noted between listening to the environment in the moment and listening to a recording of an environment while physically in a different environment is the level of “drone” that is perceived. While drone is operationally defined as “a low continuous humming sound”, in this context it refers to the constant background noise consisting of keynote sounds. These keynote sounds include the rumbling of layered conversations, relentless clanking of silverware, and an array of cooking sounds from the kitchen. While listening to this soundscape in the moment, the overall level of drone seems to be significantly less than while listening to the recorded mp3. This can be attributed to one of two core concepts from the reading.

In the eyes of Schafer, the difference in perception can be attributed to having unintentionally closed ears while physically in the environment, due to habituation of the keynote sounds. When many people first arrive at UVM, the dining halls seemed overwhelmingly loud and busy. As they are habitually attended day after day, the ear also habituates by beginning to block out constant unchanging sounds. After a relatively small portion of time, the recurring sounds of an environment will be effectively tuned out. While listening to the recording in a different environment, the body does not habituate the drone in the same way because it does not recognize the new environment as the same environment the sound was produced in.

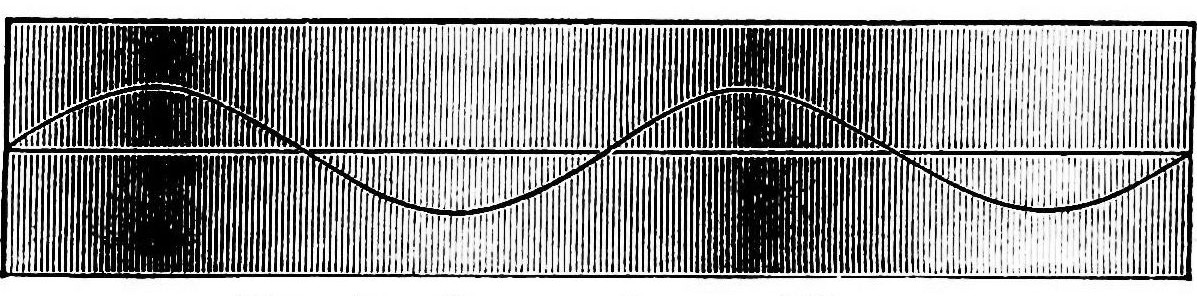

From the drastically different perspectives of Sterne or Hudspeth, this difference in perception is due to the fundamental differences in live perception versus recording technology. The human ear is a fantastically complex system that can exhibit “active process” as a sort of organic gain control. In his 2015 paper The Energetic Ear, Hudspeth writes “The active process provides a striking example of the opportunistic nature of evolution. The direct mechanical gating of transduction channels- the simplest mechanism that might be envisioned- inevitably inflicts the distortion responsible for combination tones”(Hudspeth 51). In an environment with a loud drone, the ear produces a constant tone to minimize the contrast of auditory input interacting with the stereocilia. In an environment with little to no drone, the ear would produce little to no constant tone, which would maximize the effect that auditory input has on stereocilia. In the case of a dining hall, the ear would exhibit a moderately strong amount of the active process, and minimize the level of drone perceived in the environment. When an mp3 of the environment is listened to out of context, the ear is trying to focus on all aspects of the recording and fails to adjust to filter out the drone.

In “The Soundscape”, Schafer mentions the features of soundscape and how they are important to notice while listening to soundscapes. The features of soundscape are keynote sounds, signals, and soundmarks. These features are prevalent in every soundscape and make them unique. Upon walking into the UVM dining halls the keynote sounds are generally the rumble of conversation, clanking of silverware, and the surrounding conversations of other students. These are the sounds that are not regularly noticed; they are sounds that people are used to hearing on their day to day routine. On the other hand, there are signal sounds that are consciously heard. They draw attention by being louder or different than the keynote sounds. The signal sounds of the dining halls include, the loud clunk of the bus bin being slammed on the counter, loud laughter or screaming from a table across the room and the shaking of utensils being replaced in their containers. Soundmarks are the unique sounds that are present in each environment. The unique soundmarks of UVM dining halls are the kind and welcoming sodexo staff. They positively affect the moods of every customer. Mary, the woman who swipes cards at the entrance, is UVM’s favorite worker and makes every student excited to go to the Grundle, making her a unique soundmark to UVM dining halls.

The emotions associated with being present in a dining hall have vital influence on the perceptual enjoyment of the sounds present in that soundscape. According to Murray Schafer’s essay Open Ears, a specific sound is perceived as enjoyable or unenjoyable based on its environmental context. If a sound is a marker of a positive consequence in one’s life, the sound will be enjoyed. If a sound marks an unpleasurable event or experience, the sound will be perceived as unenjoyable. This concept dates all of the way back to 1890’s psych experiments performed by Ivan Pavlov. In one of the recordings, a drink fountain being used can be heard vaguely in the background. In the setting of a dining hall, the sound of the drink fountain filling up a cup is enjoyable for certain individuals because of the knowledge that an enjoyable drinking experience is to follow. In the unlikely case of someone who potentially hates drinking anything, this sound would likely be unpleasurable.

The sounds at the UVM dining halls are not managed at all. There are a slew of noises that stay relatively constant over time and at the same time there are organic ones that fluctuate based on factors like time, weather, and culinary satisfaction. There are always going to be the keynote sounds that are constant in the background, but the things that really make soundscapes out of dining halls are the noises of the students that come and go. One determinate is the time of the day in that there are going to be more students and subsequent sounds around prime Western eating times. 6-6:30 pm is a notorious time for Simpson dining hall while students on central campus can get a break from their classes around midday at Cook. Weather also plays a role in the amount of sound in a dining hall. For example, on a cold/rainy day there are likely to be more people, and therefore noise, in the Grundle because so many people live attached to it in Harris/Millis, while Cook would have less people in it because it isn’t attached to or near any housing. There is a stigma about the Harris Millis dining hall that it has the worst food on campus and this causes people, and the sounds they bring with them, to be more likely to go to a different hall to eat. Even though this may or may not be true, the idea has already ingrained itself in UVM culture so that it cannot be reversed.

Cam Montgomery, Jack Jennings, Hannah Natale