This article was adapted from the presentation that Silver Special Collections Director Jeffrey Marshall delivered to open our November 2019 colloquium, “Interpreting the Handwritten Book: Medieval Manuscripts at UVM.”

Our Rare Book Collection includes sixteen medieval manuscript books. We can divide them conveniently into three categories: manuscripts given to the University of Vermont before the formation of Special Collections in 1962; those donated between 1962 and 2010; and those that we have purchased since 2010.

The first group includes eight books, all described in Seymour de Ricci’s 1935 Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada. Three are part of the George Perkins Marsh collection.

The first Marsh manuscript is Ascanio Savorgnano’s Copiosa Discrittione delle cose di Cipro (UVM MS 4). Savorgnano was sent to Cyprus by the gentlemen of Venice, apparently around 1572, to describe its “military capabilities.” A very similar copy is housed at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn Ms. Codex 327).

The second Marsh manuscript is attributed to King Frederik II of Denmark and Norway, and titled Van der Lehre des Reinen Godtlichen Wordes (UVM MS 5). To quote from a description of the manuscript written several years ago, “it appears to be a copy of the Danish Church Ordinance of 1537, here applied to Frederik’s new royal patrimony of Ditmarschen. The original ordinance, by Frederik’s father Christian III, established Danish ecclesiastical organization (Lutheran) and was based on the Augsburg Confession of 1530.”

The last of the Marsh manuscripts is a hastily copied seventeenth-century text of Eberhart Hicfelt’s Aucupatorium herodiorum (UVM MS 7), a treatise on hawks and hawking. It’s interesting to note that de Ricci identified the author as Richardus Hitfelt. I assume that de Ricci was relying on information supplied to him by our librarians in the 1930s, and that he was unaware of Eberhart Hicfelt’s work on the subject.

Considering the richness of Marsh’s library, now the core of our rare book collection, it is a little surprising that his three manuscripts are not more visually compelling. I don’t think he had a particular interest in manuscripts, and these may have been acquired quite casually.

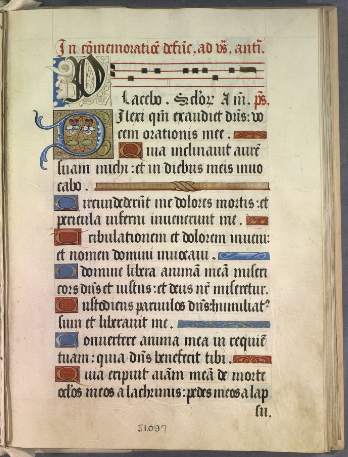

Three manuscripts among the first group were donated by Lucius Chittenden, a prominent Vermont lawyer and book collector who served in the Lincoln administration. The visual appeal of Chittenden’s manuscripts more than makes up for the modest appearance of those from Marsh’s library. They include a volume containing several works of Cicero (UVM MS 3), copied around 1400; an early sixteenth-century Italian herbal (UVM MS 2); and a Flemish prayer book from 1561 (UVM MS 8). Benjamin Franklin Stevens, the Vermont-born London bookseller, gave us In Commemoratione defunctorum, or the Office for the Dead (UVM MS 1). The last of the early manuscript donations is the statutes and ordinances of Carpeneto, Italy, written in 1458 (UVM MS 6). This was given to us by Prof. Giuseppe Ferraro, who published the text of the manuscript in 1874.

Over the more than one hundred years that followed these early donations, we acquired only one additional medieval manuscript. In 1964 a St. Albans resident left with us a choir psalter (UVM MS 12), likely made in the sixteenth century, and never returned to reclaim it. This large-format book contains three brightly colored illustrations (most like colored in the nineteenth century) and a number of hymns that feature new wording in place of partially erased letters.

Despite the fact that we have had an active collecting program since Special Collections opened its doors in 1962, our first director, John Buechler, did not focus on medieval manuscripts. And for good reasons. They were expensive, and there was little apparent demand among our faculty. Even if the resources and the demand had existed, developing a strategic approach to acquiring medieval manuscripts, nearly from scratch, would have been an enormous challenge for a librarian at a small state university.

It wasn’t until 2007 that Special Collections received its next manuscript gift. That year, Robert and Sally Fenix donated two copies of the Summa de Casibus Conscientiae of Bartholomew of San Concordia (UVM MS 9 and 10), both copied in the early 1400s. This work, a guide to confessors evaluating sins large and small, was very popular in its time

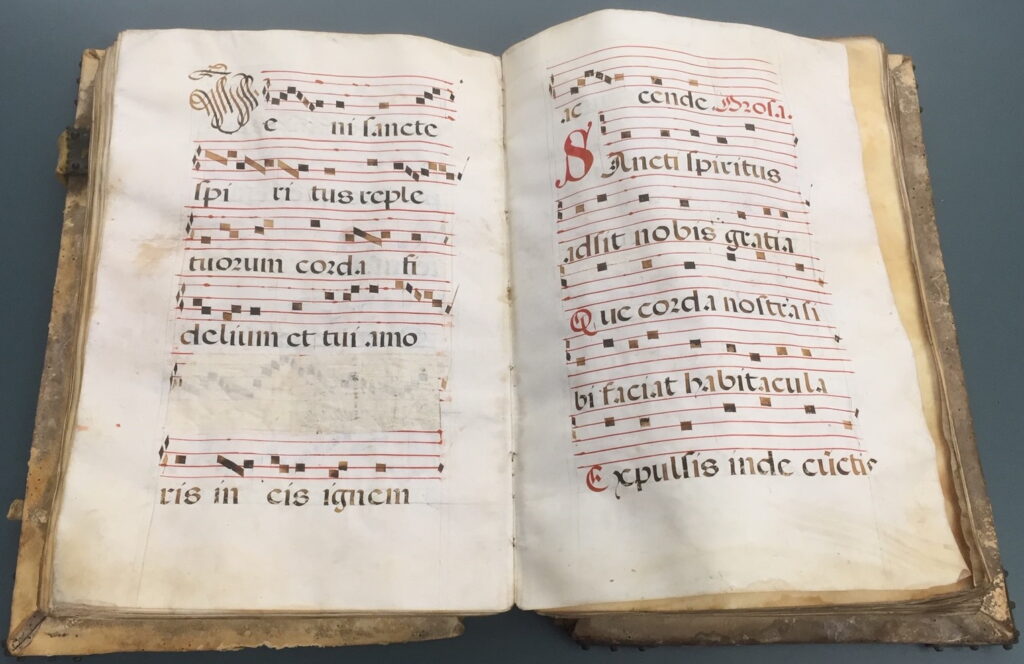

The manuscript collection came full circle, in a sense, in 2010, when David Richardson donated a very large Spanish gradual (UVM MS 11), a book containing chants for the Roman Catholic liturgy. David was the grandson of Henry Hobson Richardson, the architect who designed UVM’s Billings Library—now the home of Silver Special Collections and its medieval manuscripts.

The final category of our manuscript books includes the four that we have purchased since 2010. Manuscripts are still expensive, and their market value has soared over the last several decades as rare books have increasingly come to be seen as investment opportunities. Nevertheless, with careful management of funds from a variety of sources, we were able to acquire two important manuscripts in 2013 and 2016, Letters Patent to the Order of the Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem (UVM MS 13), a document that outlines the privileges of the Knights Hospitaller as confirmed by the French crown, ca. 1465; and a book of sermons by Johannes Nider (ca. 1380-1438; UVM MS 14), copied in Germany ca. 1445-1450. In 2018 and again in 2019, former UVM President Tom Sullivan allocated funds for the Libraries to purchase books to support teaching and research in the humanities. We were able to make two significant purchases, Les roys de la très crestienne maison de France (The Kings of the Very Christian House of France) (UVM MS 15) and the Book of the Confraternity of the Holy Name of Jesus (UVM MS 16).

The decision to purchase manuscripts marks a distinct shift in our acquisitions policy. While it didn’t make sense to buy medieval manuscripts in the past, we now have several reasons to do so. Our distinguished faculty of medievalists in multiple disciplines is making a concerted effort to promote medieval studies at UVM. At the same time, we have been developing an instructional focus on book studies in Special Collections, so these manuscript books fit into the spectrum of materials we are trying to provide for our students and faculty. On a more abstract level, we regard it as part of our mission to support research and teaching in the Humanities. Although our resources are limited and must serve a number of collecting areas, we hope that we can continue to meet the interests of faculty and students in this area.

You can see many of these items in our Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts digital collection.