Written By:

Nancy Demuth ’22

Creative Director

Connect with Nancy on LinkedIn

Many of us tend to think of sustainable business as a recent phenomenon. It’s certainly true that in the last few decades, the climate crisis has compelled a new wave of companies to benefit both people and planet through their everyday operations. But in the wise words of American poet and civil rights activist Audre Lorde: ‘There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt.’[1]

In Professor Dita Sharma’s Entrepreneurial Family Business class, we learned that notions of “sustainability” have evolved over time. While the world’s most pressing concern today is the climate crisis, previous generations have also harnessed the power of business to tackle various social and environmental problems. They might not have used the word “sustainability”, but the concept of protecting people and planet would have been familiar to them.

I joined the SI-MBA program as an international student from the UK, a country with a rich history of sustainable business pioneers determined to change the status quo. Many of them worked against the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century and had a brutal impact on the poorest people in society. For centuries, millions of working-class people labored for twelve to sixteen hours each day for little pay in dirty, cramped and extremely dangerous conditions. Workers’ rights were virtually non-existent, employers were often cruel and dictatorial, and child labor was a common and accepted reality.

This was the world that Welsh factory owner Robert Owen (1771-1858) grew up in. In 1799, Owen purchased the New Lanark cotton mill from his father-in-law David Dale. While Dale was already considered a generous employer for the time, conditions at the mill were still, objectively, brutal. As a first step, Owen immediately banned corporal punishment for children, stopped accepting child workers from the local poor house, and raised the minimum age of employment to ten.

Eventually, Owen phased out the hiring of children completely and sent his remaining child workers to a purpose-built school. He also made many other decisions which, at the time, were nothing less than revolutionary: from implementing measures to increase his workers’ autonomy and motivation in the workplace, to improving workers’ housing, to opening an adult night school for his workers (commonly credited as the first in the world)[2].

In 1807, President Jefferson passed the Embargo Act, which put American cotton exports to Britain on hold. In response, most British cotton mills began laying off their workers. Owen, however, made the highly unusual decision to keep his workers on at full pay, earning him even more respect and loyalty from his employees. His approach reminds me of Dan Price, the tech CEO who in 2015 famously took a pay cut to pay all his employees a minimum salary of $70,000.

Owen is often remembered today as a philanthropist. However, this characterization glosses over the fact that his social initiatives could always be justified on economic grounds. The social improvements he pioneered weren’t simply acts of charity, but considered business decisions – and under his management, the factory became exceptionally profitable, with returns of over 50% on investment.

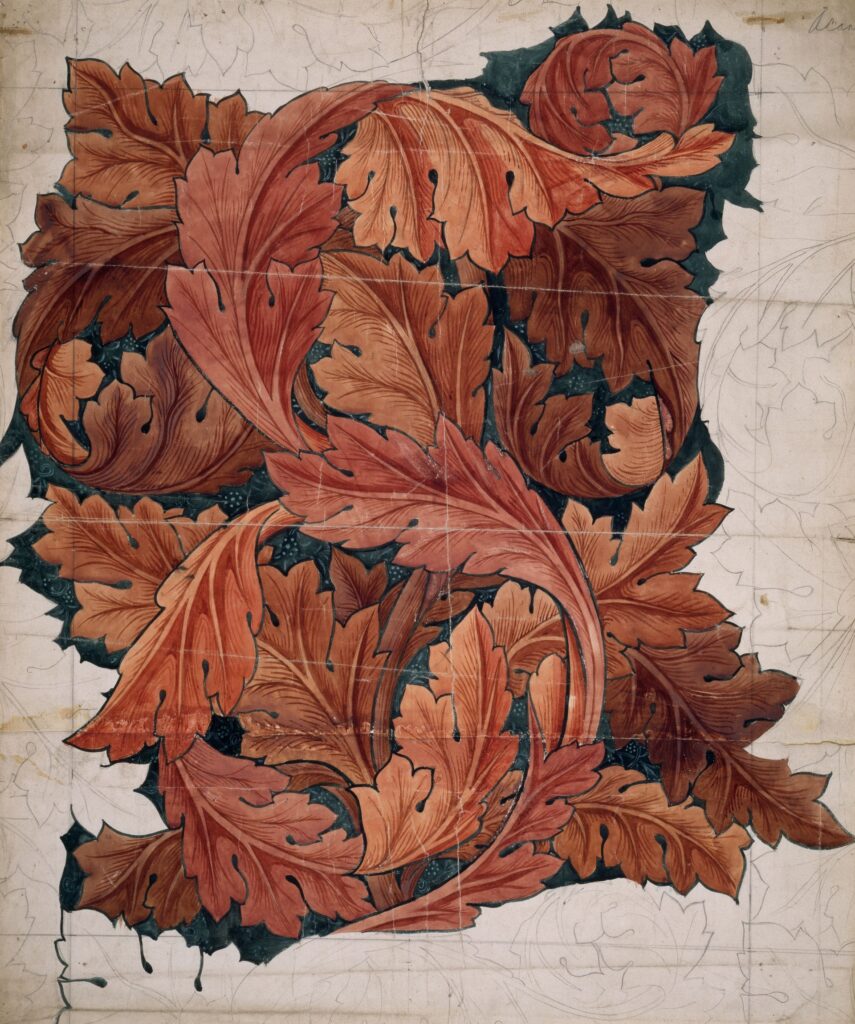

Textile designer William Morris (1834-1896) was another sustainability-minded entrepreneur whose ideas were far ahead of his time. Morris’ designs, famously inspired by the forms and shapes of the natural world, are as popular in British homes today as they were over a century ago. But fewer people are aware of the activism that accompanied his business acumen.

A committed environmentalist and campaigner, Morris was infuriated by the effects of industrial waste and pollution on the natural environment. He eschewed industrial production methods, instead opting to use small-scale, artisan production at his furnishings company, Morris & Co. He revived obsolete, artisanal production techniques, insisted on the use of high-quality raw materials, and used almost exclusively natural dyes[3]. He was also socially progressive, proving himself lightyears ahead of his time by hiring women as decorators in an era when this was far from considered a suitably “feminine” profession[4]. Even today, CEOs in male-dominated sectors tend to be far less proactive in this respect.

As an egalitarian and a committed socialist, the fact that only affluent households could afford Morris’ products was deeply troubling to him. While he never fully resolved this problem, his tactic was to educate consumers into making fewer purchases of higher quality. Today, many purpose-driven businesses still grapple with the very same issue: like Patagonia, whose striking “Don’t Buy This Jacket” campaign encouraged customers to buy less, but buy better. Morris’ message, then, seems more likely to resonate with customers in the 2020s than it was in the 1870s (at least, for those of us who constantly struggle to stop buying things we don’t need and achieve Marie Kondo levels of minimalism).

https://unsplash.com/photos/aQSZqWzzjg4

A century later, in 1976, trailblazing entrepreneur and activist Anita Roddick (1942-2007) opened the first Body Shop in Brighton on the south coast of England. This was an era long before the advent of Fairtrade certification, the trend for zero-waste stores, and the boom in natural and vegan cosmetics. But Roddick was already travelling across the Global South to buy directly from farmer groups, asking customers to use refillable bottles, and campaigning against animal testing[5]. In the profit-obsessed, Thatcherite 1980s, Roddick was seemingly the antithesis of everything a CEO should be.

Roddick was no stranger to controversy, and her decision to take the business public in 1984 angered many who felt she had compromised her principles (and she did live to regret her decision). But few would deny that Roddick truly broke the business mold and paved a path for others – particularly women – to follow. Before anyone had coined the phrase ‘B Corporation’, ‘social enterprise’, or ‘Triple Bottom Line’, Roddick had already succeeded at growing a purpose-driven, activist enterprise in an extremely unforgiving and profit-obsessed business ecosystem.

Though the world has changed dramatically since Owen, Morris, and even Roddick’s time, the problems they railed against still exist in some form today. As sustainable business students, we tend to constantly look ahead to the future at the potential of the latest technological advances to drive positive change. But more often than not, there’s also a great deal of inspiration to be found from the ingenious ideas of the past.

The opinions expressed in this article are my own, and do not represent the views of UVM or the Sustainable Innovation Review editorial team.

[1] Popova, M. (2022, January 28). Audre Lorde on poetry as an instrument of change and the courage to feel as an antidote to fear, a portal to power and possibility, and a fulcrum of action. The Marginalian. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.themarginalian.org/2020/10/18/poetry-is-not-a-luxury-audre-lorde/#:~:text=Poetry%20is%20not%20a%20luxury.,then%20into%20more%20tangible%20action.

[2] British Library. (n.d.). Robert Owen. British Library. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.bl.uk/people/robert-owen

[3] Barber, J. (n.d.). Bringing the garden indoors: How nature inspired William Morris. National Trust. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/bringing-the-garden-indoors-how-nature-inspired-william-morris

[4] Watson, A. (2019, September 9). The first eco-warrior of design. BBC Culture. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190909-the-first-eco-warrior-of-design

[5] Horwell, V. (2007, September 12). Obituary: Dame Anita Roddick. The Guardian. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/sep/12/guardianobituaries.business