EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was previously published on Impakter.com. It was written by Jason Wiff, a member of the SEMBA Class of 2017

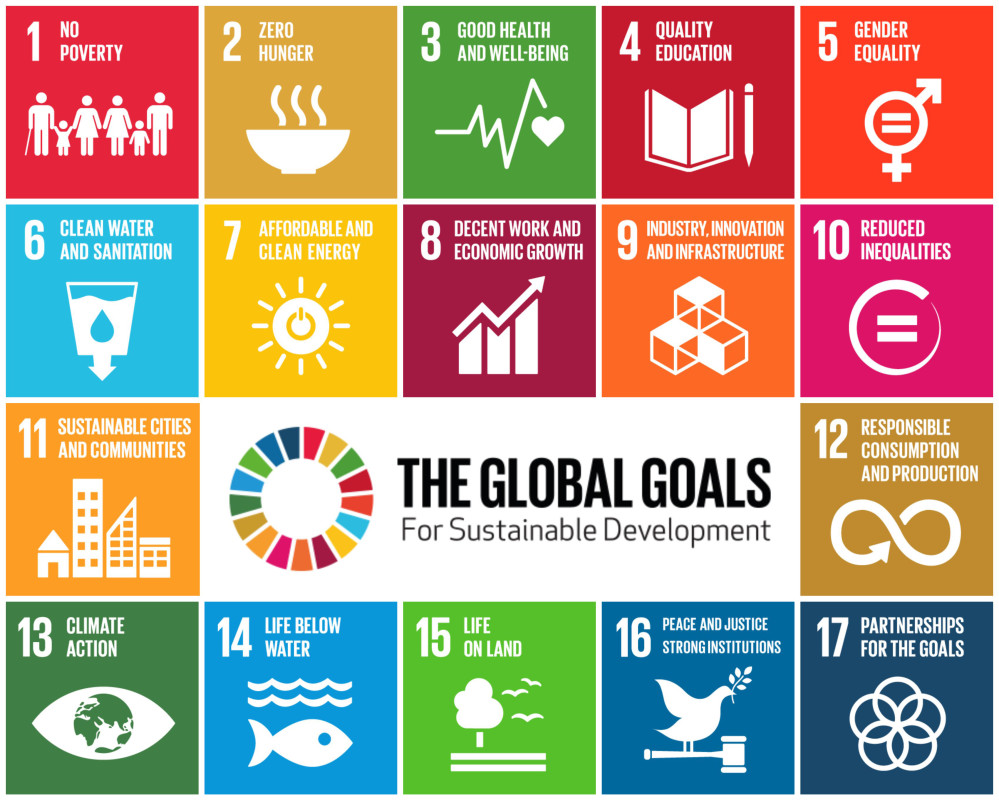

With the introduction of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, we are faced with the challenge of implementing these goals into the way we live, impact communities and use business as a catalyst for change. Stuart Hart, one of the world’s leading experts of sustainable enterprise explains his framework for making these changes a reality. This interview has been edited for clarity. Highlights of our conversation are below.

With the introduction of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, we are faced with the challenge of implementing these goals into the way we live, impact communities and use business as a catalyst for change. Stuart Hart, one of the world’s leading experts of sustainable enterprise explains his framework for making these changes a reality. This interview has been edited for clarity. Highlights of our conversation are below.

What is your definition of business sustainability?

Stuart Hart: There can be sustainability at many levels. Business sustainability provides functionality that make[s] people’s lives better in ways that are inherently cleaner or regenerative. You’re able to serve and uplift many people in the world, not just a few. Business sustainability has two components: environmental sustainability, social sustainability and financially to propel business forward.

How does this tie into the UN Sustainable Development Goals?

S.H.: The business sector hasn’t been centrally engaged and involved in these goals. The goals weren’t created with business in mind. The purveyors of the SDGs created these goals for governments and civil service organizations, with the idea that businesses would write checks to fund these goals. It’s becoming increasingly clear that expecting civil society to drive these goals through donor capital won’t get us there. The only way to get any footing with the SDGs is to engage business and enterprise sectors. There is the growing realization that this is the case. If that’s true, how do we do that? How do we engage the business sector? Enterprises have taken the SDGs and used them as a checklist. It’s not being used as a way to fulminate new, disruptive businesses. How can we convert the SDGs into something that’s compelling for business leaders?

The changes needed can’t be achieved without business. You can’t just regulate and expect change. The conventional roles have proven to not be up to the task.

Where did the idea come from to address social and environmental issues in business?

S.H.: The idea of sustainable business started over the past 20-30 years. There was this realization that the institutes that were responsible for addressing the issues just weren’t getting it done. The simple truth is that those who were assigned to fixing social, environmental, regulatory issues— the problems were overwhelming them. This has become increasingly relevant. There really has been no choice but to engage the enterprise sector. Not just in compliance, but as an active participant in the solution. The idea is to get from regulatory business is the problem, to now, how can business be a catalyst for scaling solutions to social and environmental problems while still making money. This has been a process in changing mentalities and mindsets over the past twenty-some years. There’s growing realizations that the business sectors are critical in turning things around. The changes needed can’t be achieved without business. You can’t just regulate and expect change. The conventional roles have proven to not be up to the task. This isn’t a criticism, but a realization of what needs to take place.

Our species is tied to others. But within our species, there’s a growing level of inequality. So the social side of sustainability deals with the growing number of people on our planet, toxic levels of inequality which have led to failing political systems, revolutions, violent protests and government overthrows. The idea is to have human society flourishing. How do we tackle inequality in a society that has generally excluded communities?

How does this tie into the bottom of the pyramid (BOP)?

S.H.: When people typically hear about sustainable business they typically think it’s just about the environment. It is about the environment, but it can’t be only about the environment, but how do we chart development for ourselves as a species. We’ve realized the only way to do that is to make sure we’re not the only species that can thrive. Our species is tied to others. But within our species, there’s a growing level of inequality. So the social side of sustainability deals with the growing number of people on our planet, toxic levels of inequality which have led to failing political systems, revolutions, violent protests and government overthrows. The idea is to have human society flourishing. How do we tackle inequality in a society that has generally excluded communities? This is the idea for the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP). Unless we figure out how to engage and lift the people at the base of the income pyramid, then it’s hard to imagine getting to anywhere that looks like a sustainable world. Continuing down the road of inequality won’t benefit anyone.

Are there any parts of the BOP concept you would change?

S.H.: It has undergone an evolution. Originally, it was thought that all we needed to do was create cheaper products and distribute them. In the early stages, it was really a matter of price and distribution. It has become clear that this isn’t the answer. Not just selling cheaper versions of products available at the top of the income pyramid, but collaborating with the BOP to come up with solutions that work best for these communities. Not making assumptions that products available to the top of the pyramid are also important or vital to the bottom of the pyramid. A real entrepreneur would think of this in an empathetic way, of what functionalities creating a value proposition that would be important in those communities and build a business around that.

How could an established company set up a sustainable-value framework?

S.H.: Think of it as a diagnostic tool to get a sense of what their portfolio of sustainable activities looks like. That then gives you a sense that the relative emphasis has more to do with reducing the impact of current business practices and products versus scaling sustainability to leapfrog or making outdated business practices obsolete and open up to entirely new markets. Typically what we would find in today’s businesses is that the sustainable value framework is used as a way of mitigating the impact of current products and processes.

How could sustainable concepts in the developing world be implemented into the Western world?

S.H.: One of the curious insights that has emerged is that these places don’t have fully built out infrastructure, there’s greater freedoms in some cases, and restraint in others. They’re under a different set of circumstances. Businesses and technologies can emerge and develop in China or India in ways that couldn’t work in the developed world. We begin to see that indigenous technologies might have the potential to move up market, but there are also opportunities to incubate businesses that could challenge established businesses in places like the United States. The lack of restrictions in certain areas can lead to innovative technologies and in many cases this approach has a more sustainable impact. It would be affordable with a more sustainable impact and reach more people. We can incubate these innovations into the already developed world. Instead of the developing world being a recipient of altered products from the developed world, it could very well be within these markets that technology can be created that leads to a more sustainable future.

How would you address companies that label themselves as “green” rather than being a sustainable business and how does this harm the view of sustainability?

S.H.: There are different versions of corporate sustainability. Many do a lot of talking about any small aspect of their impact and trumpet it to gain some PR points versus the company wanting to do the walking, making their business work for the community and the environment and doesn’t worry about the credit until later. Many businesses work on smaller projects within the community and that’s fine. However, there are others that might not want to make the investment beyond corporate social responsibility (CSR) for whatever reason, but those companies more than likely won’t be the ones leading us into the future.

Stuart Hart is currently the Co-Director of the Sustainable Entrepreneurship MBA Program (SEMBA) at the University of Vermont and is one of the world’s leading authorities on the implications of sustainable development and environmentalism relative to business strategy. He is the S.C. Johnson Chair of Sustainable Global Enterprise and Professor of Management at Cornell University’s Johnson School of Management. He is also the founder of the School’s Center for Sustainable Global Enterprise and the Base of the Pyramid Learning Lab, comprising seven global facilities. Professor Hart has taught strategic management and founded both the Center for Sustainable Enterprise (CSE) at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School, and the Corporate Environmental Management Program (CEMP) at the University of Michigan. Professor Hart has published over 50 papers and authored or edited five books. In 1997, he wrote the seminal article “Beyond Greening: Strategies for a Sustainable World,” which helped launch the movement for corporate sustainability.