Home | Introduction | Literature Review | Data Analysis | Conclusion | Sources

Digging into the USGA: A Story Map

This story map shows the story of the USGA through visuals and text, tracing its origins from the start of school gardens in the US and going through the end of the program.

Nationalism and the US School Garden Army

The USGA was structured similarly to the military, with an explicit intention of establishing nationalistic views in the participating children: “One and one-half million children were given something to do… that helped them to build character, and something that appealed to and developed their patriotism,” a 1919 bulletin from the Bureau of Education stated about the USGA (Bureau of Education, 1919). While Gagen explored the ways in which physical work itself was used to establish nationalistic ideals in children, the USGA used more obvious tools, too, like badges (Gagen, 2004).

According to the 1919 bulletin, privates received “a service bar with U. S. S. G. in red letters on a white background on a border of blue,” using the colors of the flag to again emphasize patriotism (Bureau of Education, 1919). Lieutenants and captains received different badges, likely as a way to incentivize students to comply and work hard as well as reinforce the hierarchy.

The physical word of gardening not only morally prepared children to be nationalistic citizens, as Gagen described, it also prepared them to be good soldiers. Not “soldiers of the soil” as youth, but actual soldiers (Gagen, 2004). A pamphlet published by the US Bureau of Education in 1918 titled “Health Education” sought to recruit teachers to enlist in the “child health service” (Bureau of Education, 1918). This program helped teachers improve child health through nutrition education, exercise, and more. It describes the program as a response to the poor physical health of young American soldiers in WWI (Bureau of Education, 1918). This reveals an assumption that children should be given resources in order to be good soldiers. The pamphlet also has a poster for the USGA and describes the health benefits of the program, showing that this connection between the USGA and the military was made at the time, as well.

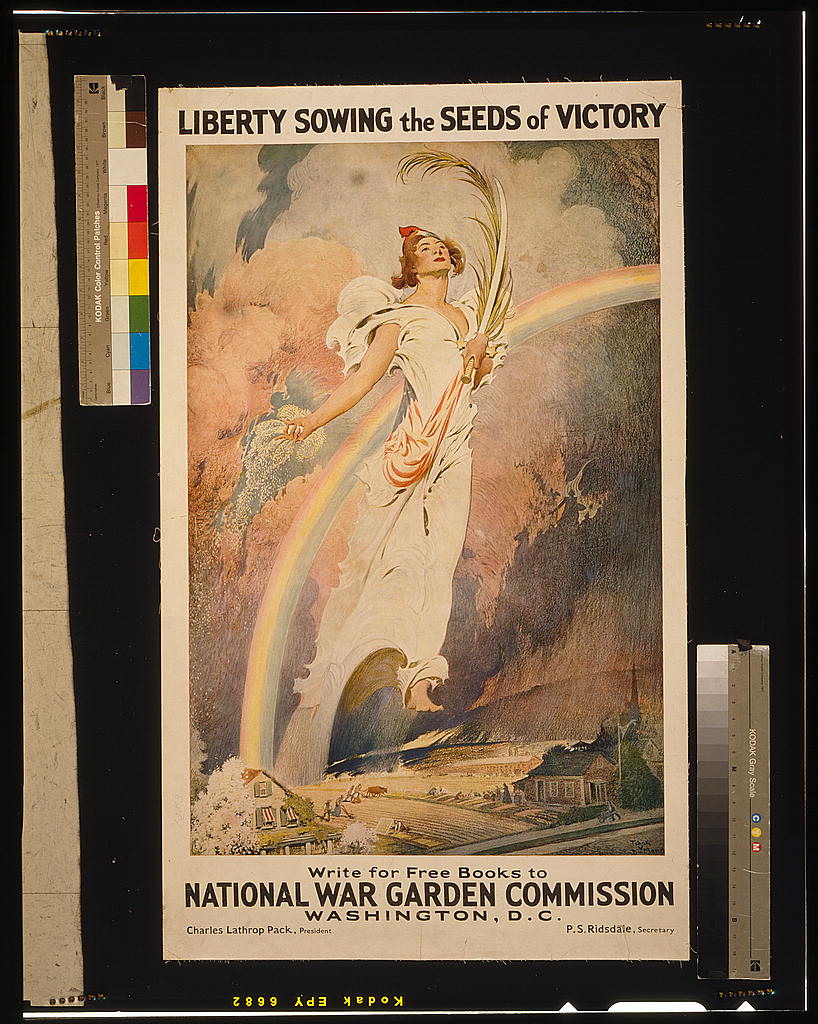

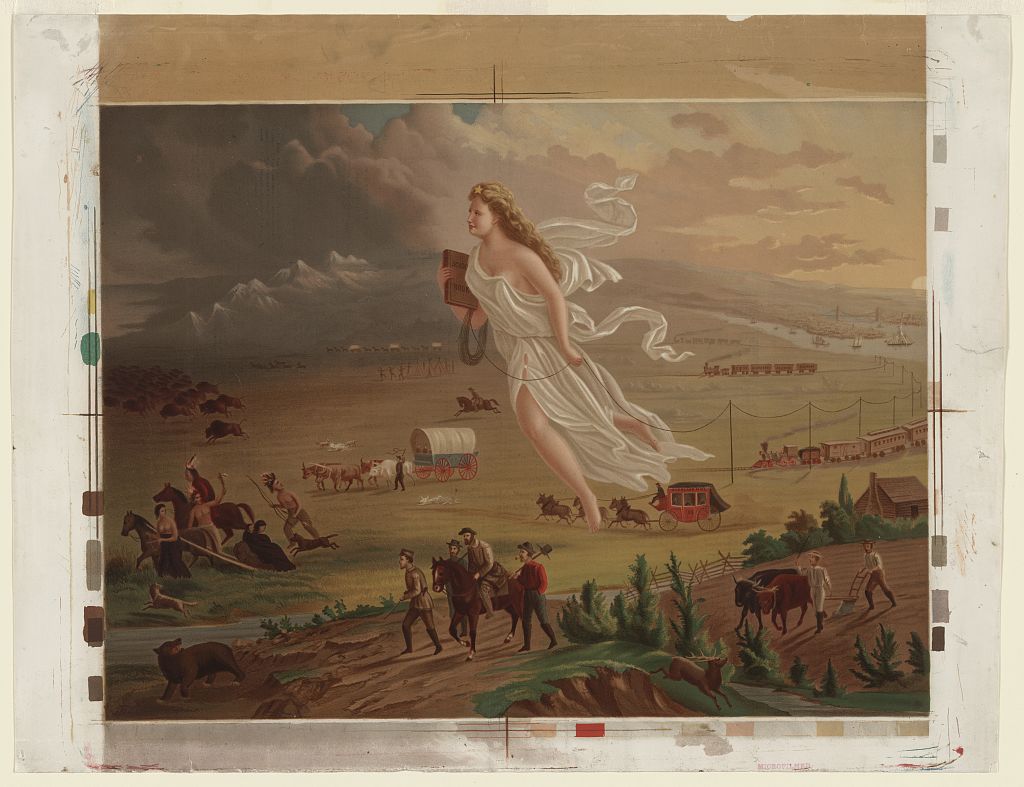

Finally, as described in the literature review, the pioneer ideal was still very relevant to nationalistic ideas and imagery. This is evident in the similarities between the painting on the right, which is often cited as a prime visual of Manifest Destiny, the idea that Americans had a duty to expand across the continent, and the war poster on the left. The USGA perpetuated this ideal by involving children, especially urban children, in farming and celebrating their work.

Bringing Farm Values to an Urbanizing Populace

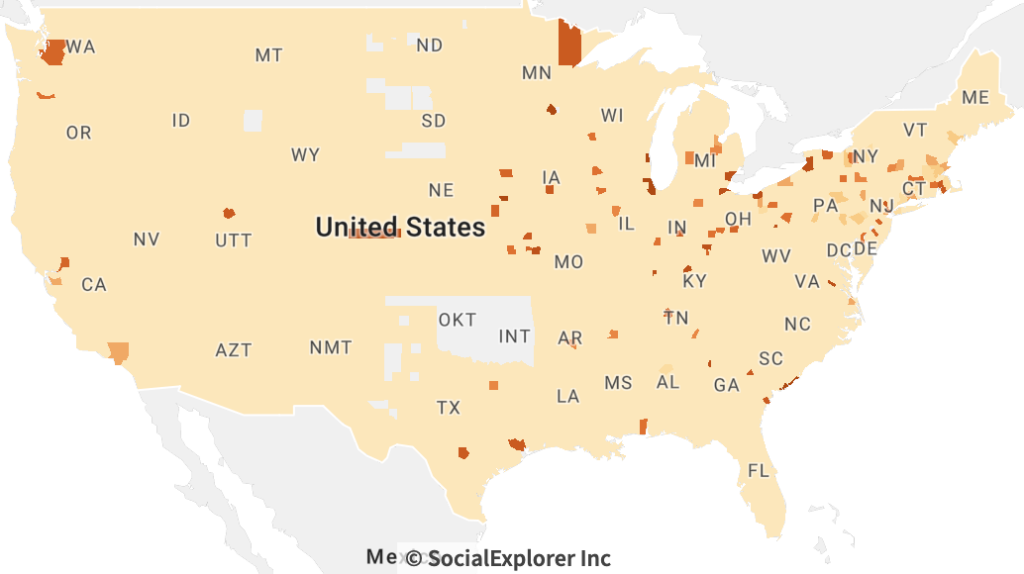

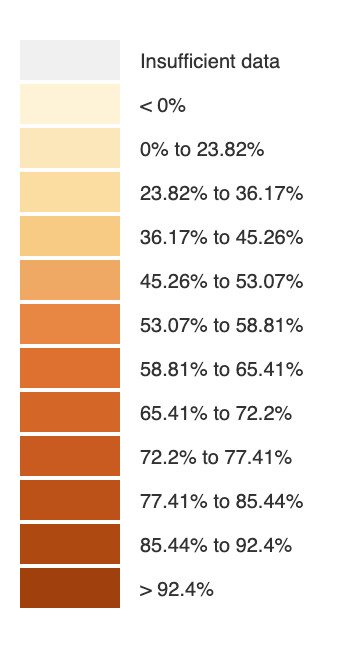

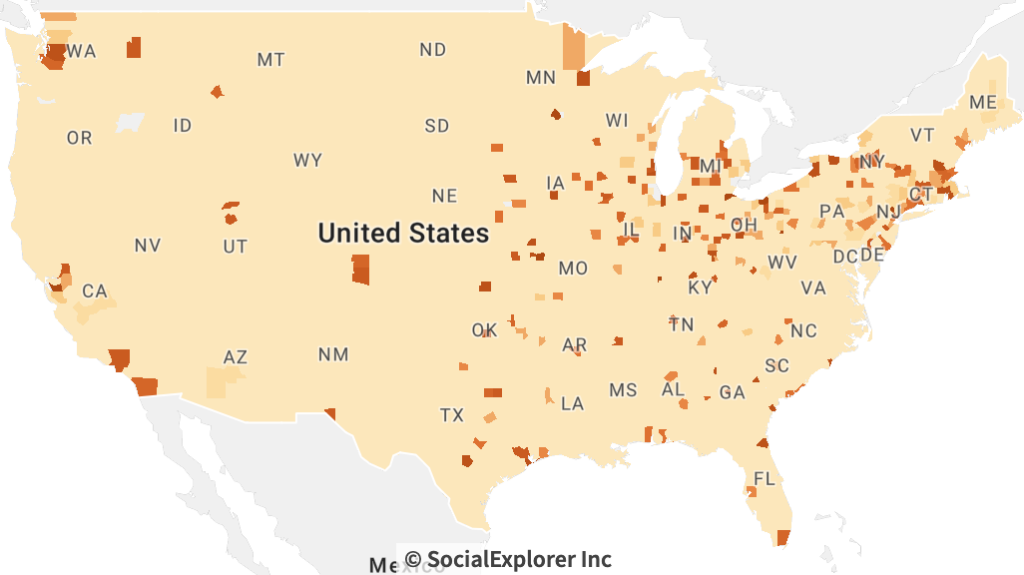

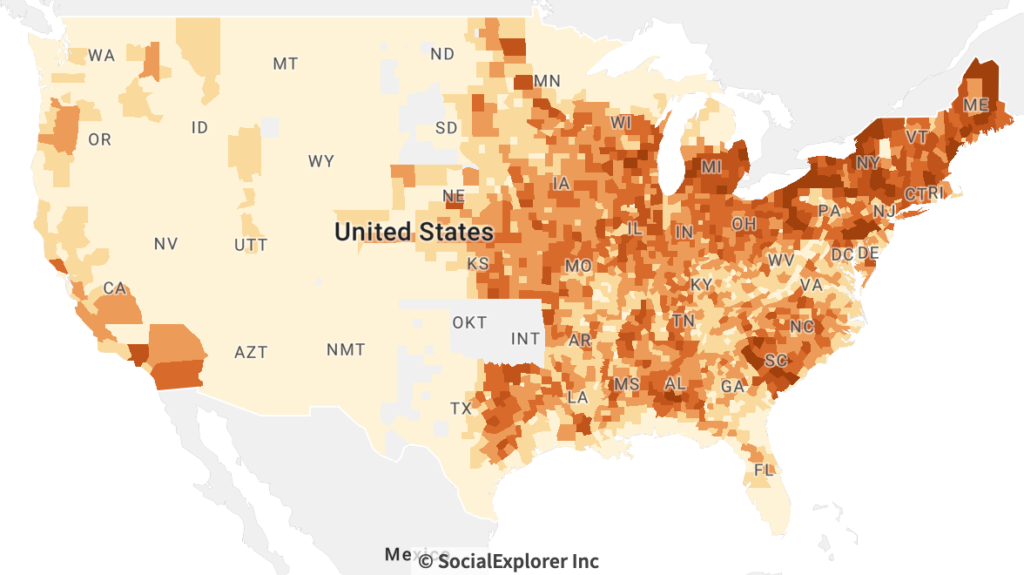

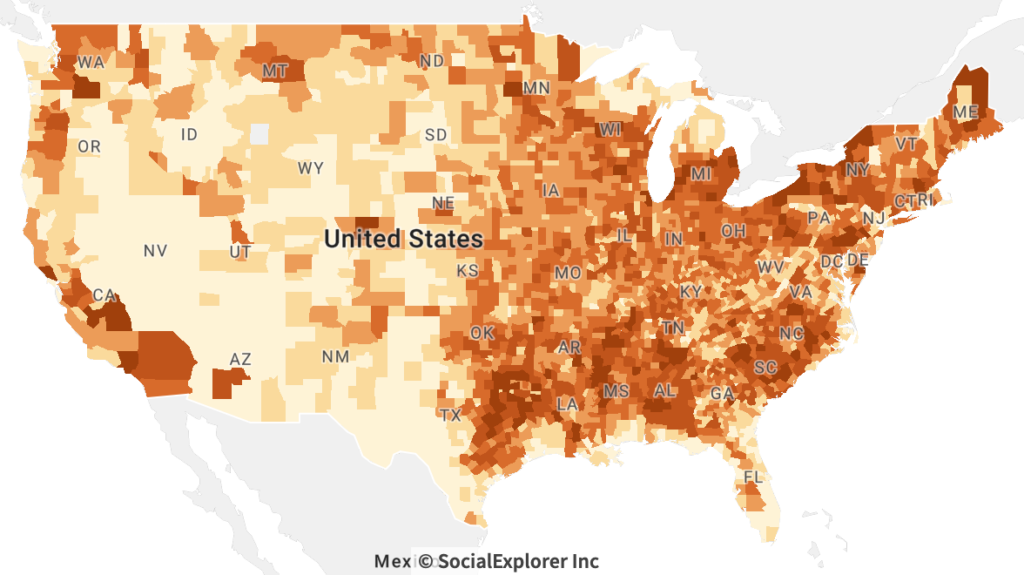

The United States was an urbanizing nation around the time period of the USGA. By 1920, the US became a majority-urban nation, according to the pre-1950 US Census definition.

These maps show an increase in urban counties across the US, especially in the eastern half of the country.

Because American identity was grounded in the pioneer ideal, urbanization presented an identity crisis. As Hayden-Smith described, this led to a shift in agriculture programming from being oriented to rural youth to becoming viewed as important for urban youth in order to homogenize values and experiences in-line with traditional American identity. As the US’s first federal curriculum, the USGA was a key way that this nationalization of identity formation took place.

The USGA was partially motivated by fears about urbanization and its results: demasculinization and loss of the “producer ethic” that Hayden-Smith described (Hayden-Smith, 2007). Since masculinity and strength was key to the pioneer ideal, boys in the USGA, willingly or not, worked to support that national identity. Finally, while the US was urbanizing at this time, the total number of farms was still increasing, especially across the midwest, as shown by the maps above. This shows that fears about a loss of agrarian knowledge may have been exaggerated.

Gardens and Education

As demonstrated in the literature review, the USGA was influenced by multiple education movements and was related the first national curriculum (Trelstad, 1997; Kohlstedt, 2008; Hayden-Smith, 2007). The decision to implement a nationally standardized curriculum reveals that education was viewed as important. Therefore, attending school and being instructed, morally and technically, could be seen as part of children’s civic duty and right.

Children: Producers or Consumers?

Hayden-Smith described how children were recruited with slogans like “he who produces is a patriot” (Hayden-Smith, 2007, pp. 21) This envisions children as producers, giving them agency and putting them in a role we would now describe as adult. However, other wartime propaganda, at the same time, used children in a fundamentally different manner.

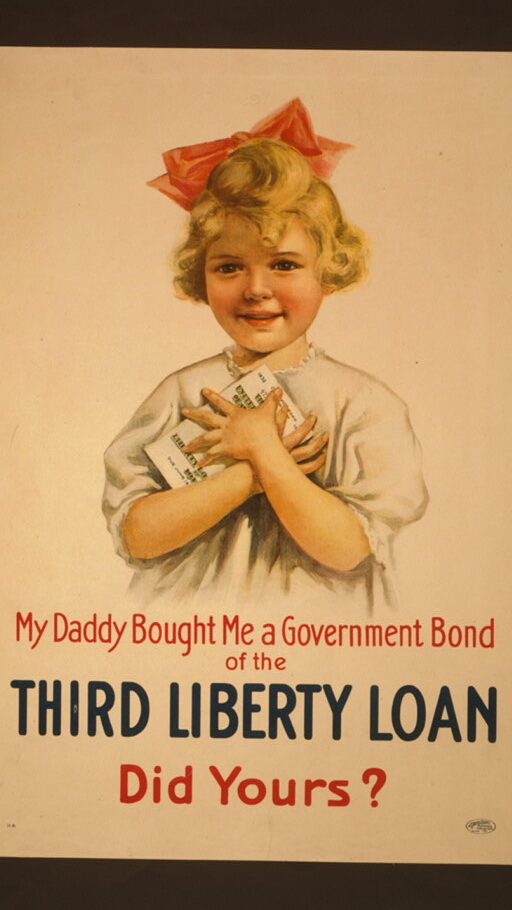

This poster is both directly and indirectly targeted to parents. It envisions parents as the ones who will take action (buying a government bond), not the children, as opposed to USGA posters that recruit children to take action themselves. It also draws upon the view of children that was emerging at the time as a result of consumerism, as Chudacoff described (Chudacoff, 2007). In this view, children are innocent, but also consumers and manipulators of their parents. This poster relies upon the assumption that children will be able to successfully convince their parents to purchase something. The roles of producer and consumer are very different, but they could both be viewed as civic roles of children.

Overall Impact of the USGA

| 1,500,000 children enlisted |

| 20,000 acres of “unproductive” land was used |

| 50,000 teachers received gardening instruction from the Bureau of Education |

| 1,500,000 leaflets were distributed by the Bureau of Education |

| In Salt Lake City alone, 5,200 mothers “actively supported food production in the schools” through 62 parental associations |

While the USGA impacted 1.5 million children, it ended in 1919. Like how the USGA focused on improving conditions in urban areas, so too did the contemporaneous Progressive Movement. As conditions improved, this helped drive urbanization. By 1920, 51.2% of the US population lived in urban areas according to the pre-1950 urban definition in the US Census. This long-term demographic shift probably led to an increased framing of children as consumers, overwhelming the impact of the USGA on the nation’s understanding of children’s civic roles.