Introduction | Literature Review | Data & Analysis | Conclusion | Sources

Schooling in the US South in the early 20th century proved to be an extremely broad topic, with many factors influencing multiple aspects of how society saw childhood in the region. The main dividing line in the conception of childhood in the US South was race. Race divided many of the primary educational influences like labor and funding. This division then went on to further separate the conceptions of childhood between races.

To understand the divides in Southern schooling in the early 20th century, we must have a grasp on what came before the turn of the 20th century in the South to establish motives of different groups to become educated. Following the conclusion of the Civil War there was a large population of black southerners that had previously been barred from education. Before emancipation, education of slaves was legally forbidden in the South (Margo, 1990). This meant that rates of illiteracy among their demographic were extremely high, but given the lack of freedom awarded in the past, black southerners, particularly in subsequent generations, valued education as a means to utilize their freedom. Even in White Southern society, illiteracy rates were already higher than the more industrialized North (Margo, 1990). However, in elite Southern society, literacy was seen as crucial in both status and practicality. This contributed to the ‘Lost Cause’ narrative that a Southern defeat in the Civil War was inevitable due to The South’s educational and industrial weakness (Edwards, 2020). This motivated southern elites to educate the masses of rural populations in the region. While it was a given that the White population would be included in these efforts , at least in theory, there was much more debate on whether black populations would be allowed to participate (Edwards, 2020). Many Jim Crow Era white elites feared that an educated black population would lead to a return of the Reconstruction Era political landscape where majority black populations in states like Mississippi would replace the now entrenched white ruling class (Anderson, 2005).

Others believed that education of black southerners would be useful for the creation of a class of low-skill laborers in their future visions of an industrialized South. Much of the industrial work in The South prior to the turn of the 20th century and even beyond was in the textile industry and worked by White children. This fact could not neatly fit in White elites visions of an educated white society to beat the Lost Cause narrative. Therefore, the white ruling class saw black southerners as a population to be exploited either as an uneducated underclass or as purely an industrial workforce (Anderson, 2005).

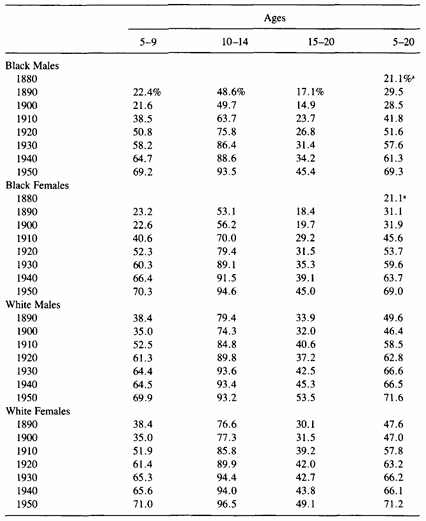

The point in which this plan to educate the South was put into motion around 1890 when Alabama localized how communities could spend school funding, effectively eliminating funding for the black population in the state (Anderson, 2005). Soon, much of The South followed suit and allocated school funding based on race. Prior to this point, state funding allocation was fairly equal, leading to southern black illiteracy rates falling from 90% to 50% by 1900 as younger generations were able to utilize their newfound public education systems (Margo, 1990). Following Alabama’s localization of school funding, the distribution of funding dramatically shifted. Prior to the change, 44% of funding went to the black population of the state, which constituted 44% of the school-age population. By 1930, that figure had changed to 11% of school funding even though they made up 40% of the school-age population (Anderson, 2005).

“A negro woman, who had attended school only four weeks in her whole life, explained that for that reason she is “pushing” the children – she wants them to get some “learning.”” – The Children’s Bureau

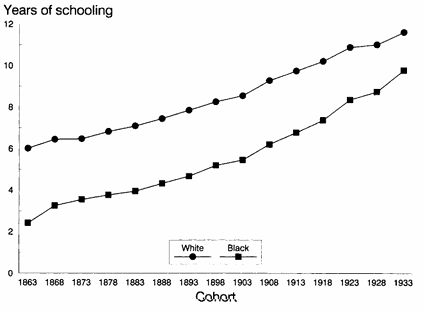

Despite the inequality in the distribution of school funds, black communities in the South were not deterred from becoming educated. While black school attendance lagged behind white school attendance for most of the early 20th century, year after year, the gap continuously closed (Margo, 1990). This can be attributed to 3 reasons; the value attributed to education by black communities, the increasing availability of private institutions, and the increased focus on industrial labor in Southern cities. As seen in the quote from a Children’s Bureau above, the general attitude of black parents was that education was necessary to maintain their civil liberties. As previous generations were not allowed education, education was seen as a necessary part of exercising freedom (Anderson, 2005). This could be seen as every subsequent generation had higher school attendance than the previous, as well as higher mean years of schooling.

The increase in private institutions was another factor that led to the increase in the quantity of black schooling, as seen above, and also the quality.

The chart above shows a consistent rise in the number of years of schooling for both black and white children in the U.S. South. For white children, this was mostly due to increased attention from Southern public officials on raising public educational standards throughout the South. Much of the focus was on extending education to upper grades. In Georgia, between the years 1904 and 1916, the number of public secondary education institutions increase from 4 to 122 (Anderson, 2005). Black children were left out of this trend as none of the 122 schools accepted black students. This was not isolated, but a trend seen throughout the South (Anderson, 2005).

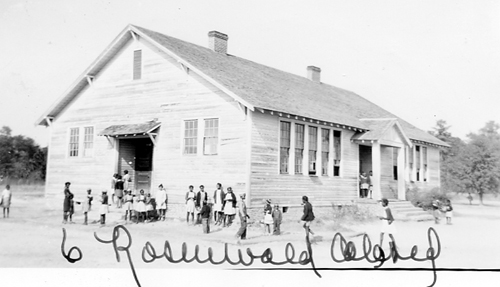

The increasing prominence of private institutions can explain the trend of rising attendance and increased years in black student populations. Rosenwald Schools, such as the one seen here, were integral in the education of black students throughout the South. Despite the poverty of the region, between the years 1914-1936 black communities in the South raised $4.7 million for the construction of Rosenwald schools alone. This led to the building of 5000 schools across 66% of southern counties and an explosion of school attendance and average years of schooling among black southern youths (Anderson, 2005). However, despite these massive gains it is worth highlighting that funding for these schools was largely payed out-of-pocket by already impoverished black communities. Education taxes they payed were not used to support the education of these same communities. This led to a phenomenon of “double taxation” where black communities had to pay double that was white communities for a semblance of similar educational standards (Macleod, 1998).

Rosenwald Colored Clarendon County, South Carolina. Source: South Carolina Department of History and Archives

The final factor in shifting educational trends in the South was the region’s shifting labor dynamics. As the South began industrializing, more and more children were pulled into the labor force. Many of the children in industrial labor were poor whites working to support their families (Walters, 1993). This led to a slowing of the growth of white education as Southern compulsory education laws gave numerous exceptions for children laboring in order to support their families.

On the other hand, black communities were primarily rural. As industrialization attracted many impoverished southern whites to cities, black families left in agricultural labor were largely ignored by public education systems. This led to a deficiency in the number of school facilities available to agricultural families, both white and black (Walters, 1992).

“One mother explained that her 9-year-old boy would have 3 1/2 miles to travel to

school – 7 miles the round trip – the winters are hard and he has so

many colds that she has not sent him.” – The Children’s Bureau

Along with exceptions to compulsory education having to do with helping parents with labor, many Southern states also made exceptions for children too far from a school (Cope, 2023). Agricultural labor itself was not as large of a burden as industrial work due to agricultural labor having predictable periods of intense labor and other period that required fewer hands on the farm (Walters, 1993). This allowed for schools to close during times of sowing and harvesting and reopening at other points in the year (ibid). This was in contrast to industrial labor which was worked year around. This meant that labor wasn’t as prominent of a factor in limiting rural southern education as lack of educational opportunities and resources (Walters, 1992). And since black populations made up a large part of rural population in the the early 20th century, it effectively meant black populations themselves were denied sufficient educational resources by the state.