Home | Introduction | Literature Review | Conclusion | References

In March 1902, a poor farmer traveled to a hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. He complained that for many years, he had a recurring illness that appeared every spring. While the doctors noted that he was impoverished and had always eaten bread made from Indian corn, it was not until years later that this mysterious disease was recognized to be pellagra (Etheridge 1972). While pellagra had never before been reported in the United States, epidemics had been recorded in Europe since the mid-1700s (Crabb 1992). It was a serious problem in Italy, where it was considered to be a peasants’ disease. Because impoverished people in Italy tended to eat lots of polenta, a dish made of cornmeal, it was originally believed to be caused by eating moldy or rotten corn rather than the corn itself lacking important nutrients (Roe 1973).

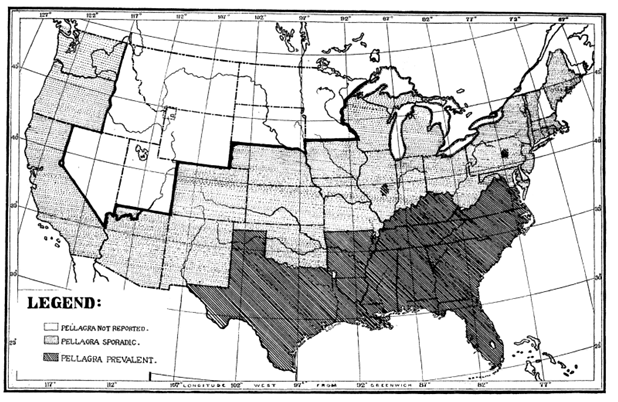

Pellagra was first acknowledged to be a discrete disease in the United States in 1907 (Duffy 1990). Cases rapidly grew throughout the south until in 1910, it was considered a full-blown epidemic (Crabb 1992). This map from 1912 shows how widespread the disease was throughout the South.

Dr. Joseph Goldberger, a physician who worked for the United States Public Health Service, was appointed to research the disease and find a solution (Bracken 2013). Goldberger combined both observational and experimental research to determine pellagra’s cause. First, he noted that at the South Carolina State Hospital for the Insane, only inmates suffered from cases of pellagra. He concluded that the disease must not be contagious between people, or else the nurses and other hospital employees would suffer from the disease. He observed that the nurses had more varied diets that were supplemented by outside meals. The nurses also had first pick in the cafeteria and would pick better foods like milk and meat, leaving the inmates with the undesirable, cheaper food.

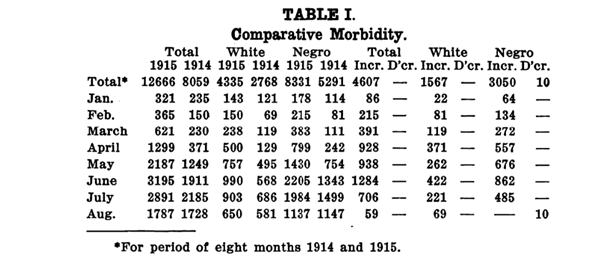

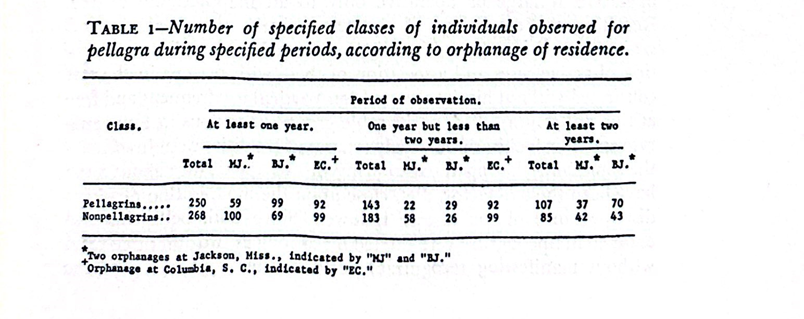

Goldberger performed his first official pellagra experiment in two orphanages in Jackson, Mississippi (Bracken 2013). A shockingly high number of the children in these orphanages suffered from pellagra. Goldberger supplemented their diets with eggs, milk, legumes, and meat while reducing the amount of corn. At the same time, he kept sanitary and hygienic conditions the same. The pellagra in almost all of the children completely resolved or significantly improved with very low rates of recurrence. Goldberger said this proved that pellagra was a dietary disease, not sanitary.

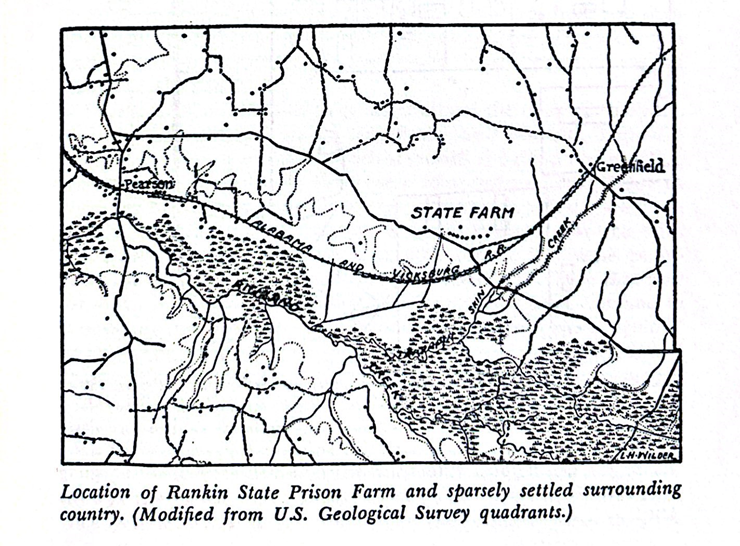

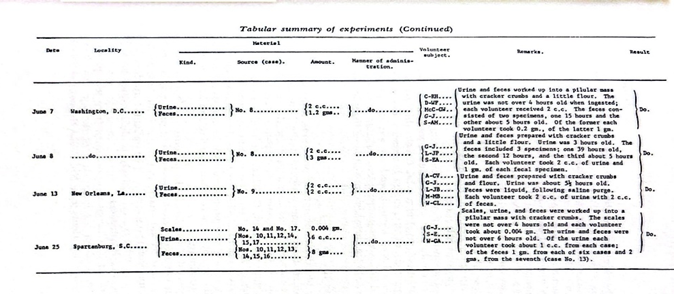

He continued his experiments on prison inmates, who volunteered in order to receive a pardon from the governor, and received similar results. Shockingly, Goldberger even injected blood from pellagrins into himself and consumed feces and other bodily excretions to definitively prove that pellagra was not a communicable disease.

This map shows what the surrounding geography of Rankin State Prison Farm, where the experiments were performed, was like. Located in central Mississippi bordering the city of Jackson, it was a very rural area at the time with few inhabitants.

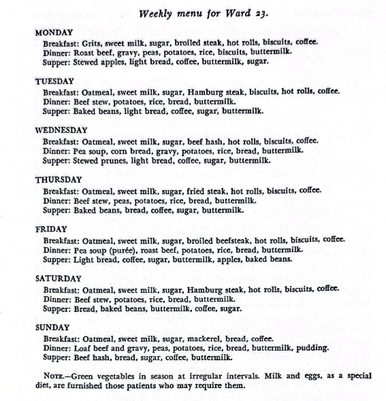

Goldberger’s experiments were largely performed at institutional facilities in the South. This is a sample menu from an asylum where he attempted to reverse the effects of pellagra in patients and was successful.

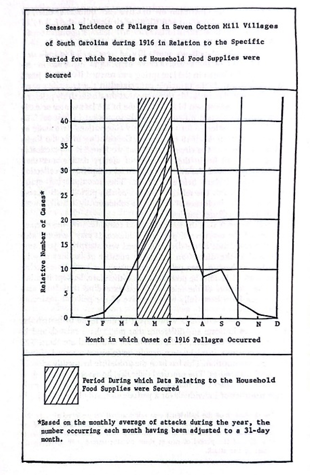

This chart shows the incidence of pellagra in mill villages in South Carolina, where children were especially vulnerable to the disease. Cases tended to spike in the spring after a winter of eating less nutritious foods.

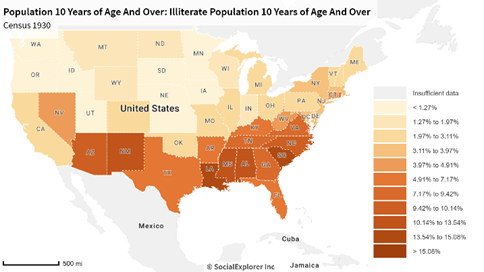

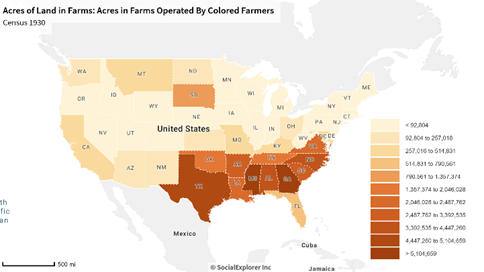

Education in the south played a role in the pellagra epidemic. Considered a disease of poverty, many victims were uneducated. Illiteracy rates in the south were much higher than in the rest of the country. The cotton monoculture and sharecropping system also led African Americans to be at a disadvantage, although both the government and experimental scientists ignored them as a factor when investigating pellagra.

Pellagra is a devastating disease that ravaged the American people for decades. It was intrinsically tied to geography: while almost all pellagra cases occurred in the South, it was the federal government in D.C. and Northern scientists and politicians that inserted themselves and tried to save the South that they viewed as inferior. Even in the early twentieth century, the South proudly clung onto its pride and national identity from the Civil War era. The entire economy of the south was reliant on cotton, which in turn weakened them by making them lean heavily on crops imported from the Midwest. The cotton monoculture depleted Southern soil of nutrients and caused them to produce very few food crops for themselves.

Tensions between the North and South were still extremely prevalent in the early twentieth century. The South did not want to be seen as weak or incapable of supporting themselves, and they rejected any help they were offered from the federal government. They were angered by Northern scientists saying that pellagra was a dietary issue. They did not want the South to have the reputation of struggling to feed itself. Being forced to stop relying on cotton and diversify both their income and food sources naturally decreased pellagra incidence rates. This demonstrates how the cultural identity of a geographical location can affect its vulnerability to a disease and the response to cure it.