Home | Introduction | Data and Analysis | Conclusion | References

The Child Labor Factor

In the beginning of the twentieth century, farmers in the south were struggling to survive as crop prices declined. Many of them turned to working in cotton mills. The textile industry was rapidly growing in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and people were beginning to call it the Lowell of the South (Vecchio & Walker 2019). It is believed that by 1905, at least 1 in every 6 white persons in South Carolina lived in a mill village (Engelhardt 2011). These mill towns were very isolated, and employees rarely left. Children attended school on-property until they, too, were old enough to begin work in the mills. In 1907, August Kohn from the South Carolina Department of Agriculture highlighted multiple children working in Spartanburg mills. Lewis Hine also photographed many of these children during his work for the National Child Labor Committee.

Although Spartanburg was referred to as the Lowell of the South, it was far from it. The northern and southern US states were still very separate entities, both in their values and economic industries. While the South had the desire to industrialize and prosper financially like the northern states, it also shunned northern policies (Cope 2023). The South was very rigid in its cultural identity and did not want to be infringed upon by the North. While policymakers in the North lobbied for child labor regulations, the South resisted this. Firstly, due to their much smaller number of factories and mines, they did not believe that they had a large number of children at risk of being harmed or killed at work (Cope 2023). Furthermore, difficult, labor-intensive jobs were thought to be the norm for black workers. They were expected to be desirable. However, cotton mills largely employed white families. This turned attention to child labor in the industrial South.

Children as young as six would do work such as sweeping floors while older children, around twelve to thirteen, could work the looms (Vecchio & Walker 2019). Because many of these children did not wear shoes while working, they were especially susceptible to contracting diseases. In 1900, over 30% of mill village children were known to suffer from hookworm, another disease that was particularly awful in the southern US states. These mill children were also devastated by pellagra (Engelhardt 2011). Many of them were also forced to work earlier than they should due to their parents suffering from pellagra and having to support the family in their parents’ stead.

Cotton: The Possible Root of Pellagra?

After the Civil War, the American South held onto its pride (Crabb 1992). They were proud of the cotton industry and did not want to change the system. The monoculture degraded the soil and eventually led to a severe agricultural depression. The tenants on plantations, poor sharecroppers, relied on commissaries for their food intake (Roe 1973). Many of the farms in the southern states were operated by people of color. The main products being sold consisted of cornmeal, bacon, and molasses. Tenants were also often uneducated and/or illiterate (Crabb 1992). Their debts would mysteriously increase each year while their incomes declined.

Shockingly, even though the south relied so heavily on cotton for its economy, the cotton industry experiencing a disruption drastically reduced the rates of pellagra (Clay et al. 2019). Poor agricultural societies that rely heavily on cash crops show a trend of suffering from malnutrition. When comparing two mill villages, it was found that the village located in a region with diversified farming had no pellagra. The village market supplied fresh meat and vegetables. The other village offered no alternative to the company store and was situated in a cotton-dominated region, where there were not many farmers growing vegetables or raising livestock. This village had the highest pellagra incidence rate compared to other mill villages in the study (Marks 2003).

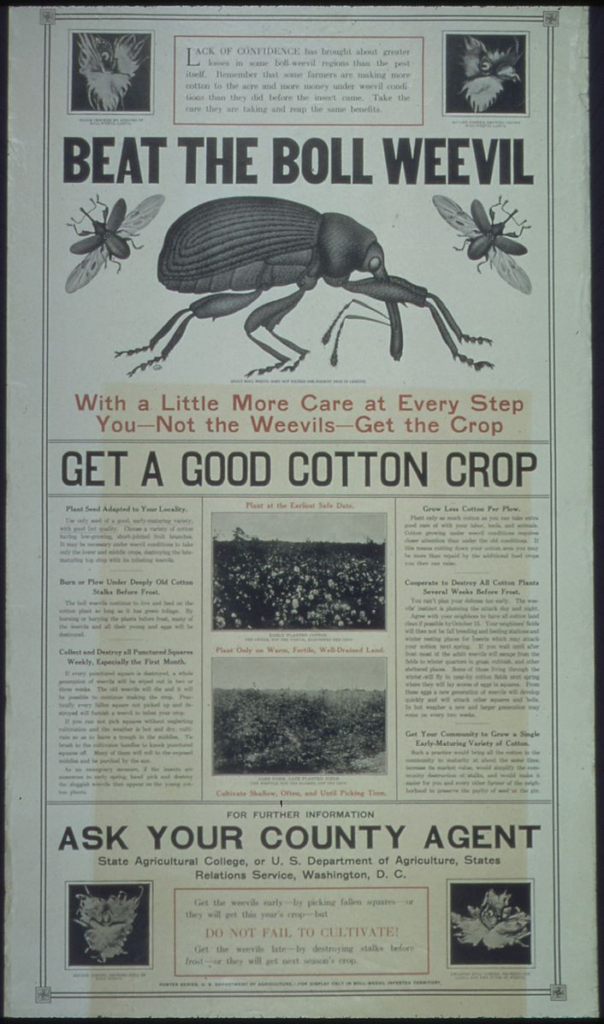

In the early twentieth century, the boll weevil, an insect that decimates cotton fields, was tearing through the American South. This led farmers to stop focusing all of their efforts on cotton and begin producing a more diverse set of crops, allowing the surrounding populations to have easier access to niacin-rich foods. This even had an effect on black children’s school enrollment rates: since less labor was required in the cotton fields, black children began attending school at higher rates. At the time of the pellagra studies, African Americans were often left out of the equation (Marks 2003). It was assumed that they had the same diet as white workers, when this was not the case: they generally consumed smaller amounts of food per capita, and they ate less foods that could help prevent pellagra like salmon and milk.

The Southern Identity

Although Dr. Joseph Goldberger proved fairly early on that pellagra could be cured through a diet change, southern physicians shunned these beliefs and vehemently declined help or any government assistance (Crabb 1992). A Jewish man from New York, Goldberger was an outsider. Pellagra continued to cause many deaths every year until his conclusions were finally accepted and a coordinated public health effort was begun twenty years later. Because of this slow reaction, pellagra was not completely eradicated until the 1940s.

After seeing the gravity of the epidemic in the south, President Warren Harding published a letter nationwide calling for food assistance to help the south combat pellagra (Crabb 1992). Southern citizens were incredibly insulted by this action and refused to accept help. They did not want the south as a whole to be labelled with the stigma of poverty, nor did they want the implication that they could not survive without northern help.

“Famine does not exist anywhere in the South, and we fail to find a general increase in pellagra.”

– The United Daughters of the Confederacy

The South was victim to a place-specific stigma (Chacko 2006). While we now know that many citizens of the South were suffering from diseases such as hookworm and malaria, at the time, the North sneered at them and thought them to simply be lazy people that did not want to work. With their refusal to industrialize, they were a stain on the country and a “hindrance to national progress.” (Chacko 2006). Even within the South, there was a spatialized marginalization caused by pellagra. Due to its prevalence in rural areas, urban areas were thought to be immune from the problem. Victims of pellagra (pellagrins) were ostracized and avoided because the disease was initially believed to be contagious.

Ironically, only after a natural disaster did the anti-pellagra campaign gain momentum (Etheridge 1972). In 1927, the Mississippi River flooded throughout 12 states. The Red Cross gave aid to many states and after seeing the successful response, southern physicians finally endorsed Goldberger’s ideas.