Background

The orphan train movement was a welfare program orchestrated by Charles Loring Brace, which ran from 1854 to 1929. This program was instituted because reformers saw the abundance of poor children living on the streets of major Eastern cities and decided to transport them by train across the country. At first, the conditions on the orphan trains were not ideal, with the children basically being transported in cattle cars, but the train car conditions improved as time went on. Additionally, there were no formal placement programs after the children were transported, although there were agents that went ahead to advertise the children and help them find families. During its operation, this program placed over 150,000 children in new homes across 45 different states, as well as Canada and Mexico.

Poverty

A large majority of the children came from New York, where factors like the civil war had caused a heightened state of economic turmoil in addition to the rampant overcrowding in the city. In fact, “the lower East Side of Manhattan was the most crowded area in the world: The population density of 250,000/square mile was twice that of the most crowded areas of London. Waves of immigration, begun by the Irish following the potato famine of 1846, packed a mass of poorly fed humanity into tenements, with unclean water, inadequate sewage and no facilities for preparation and storage of food” (Solokoff, 1993). This highlights the theme of poverty because with a population that dense, there were not enough resources or jobs to go around, so many people were unemployed and their families had to eke out a living without consistent income. Due to the high levels of unemployment and poverty, “children as young as five were forced to find ways to keep themselves and sometimes even their families from dying of starvation” (Rohs, 2012). This relates to poverty because the location that children grow up in can completely change their childhoods, as the rates of poverty in the city were much greater when compared to poverty rates in rural areas. Many of these children worked as “newsies”, where they sold their papers for a penny and experienced some of the worst working conditions in America, having to endure harassment, muggings, and poor weather conditions. This shows how these children and their families were so poor that they were willing to endure terrible conditions in order to make just a little more money to bring back to their family and help put food on the table.

Riis, Jacob A. (1888-1889). “Street Arabs in the Area of Mulberry Street”

The Home

Many of the orphans sent away on the orphan trains had already been part of other programs run by the Children’s Aid Society. There were also children who were referred from the courts or from parents who gave them up willingly. Additionally, although the children were considered to be orphans, the reality was that “about half of these dependent children were orphans; the other half had one parent living” (Gish, 1999). Because of this, many children had to actually get permission from their parents to be sent away to their new lives. This relates to the home because parents of these children were unable to give their children a proper home, so they had to send them away to give them a better life on the other side of the country. However, the leaders of western towns believed that the high number of emigrated children “reduced the number of good quality farm homes for local dependent children, leaving only those who wanted children for the work they could provide” (Birk, 2012). Because of the influx of children from the cities, the dependent children from the area were unable to find the homes they needed. This relates to the home because the children from the cities were being taken advantage of, as some of them were not being placed in homes that raised and nurtured them, but instead they were being placed with farmers that just used them for cheap labor.

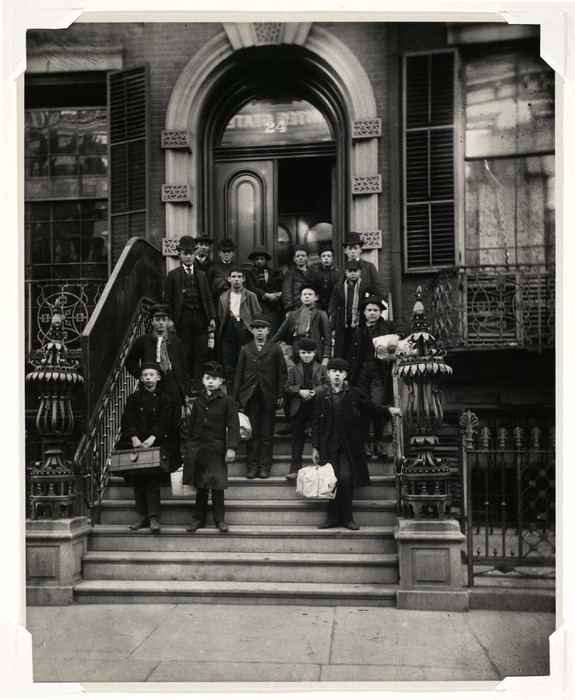

Riis, Jacob A. (1888-1898). “Children’s Aid Society: Going West”

Change

The selection process was quite overwhelming for some of the children. In each town, children left the train to go to some community gathering place, like a town hall, where those who did not already have an arranged family “were lined up for interested adults to view and select” (Cook, 2017), similarly to an auction where they could be selected by prospective parents. This relates to change because these children had been separated from their families and had their whole lives turned upside down in just a few days, and then they were forced to wait and see other children, who were younger or seen as more able, to be picked before them, continuously worrying about what would happen if they weren’t chosen. In addition to this, the program “did not consider the children’s religion when decisions were made about where they should live” (Rohs, 2012). For example, children who had been raised protestant or jewish could have been forced to worship Catholicism or another religion that they knew nothing about. This relates to change because religion was a core aspect of a person’s life, so being forced to change it based on who chose to adopt them could have been quite traumatizing for children that experienced this.

Home | Introduction | Literature Review | Data and Analysis | Conclusion | References