“Dealing with Delinquency” in 1880 – 1940

The New York Juvenile Asylum

The New York Juvenile Asylum is one example of an institution that held dependent and delinquent children. It was founded in 1850 as a result of a bill passing in New York. It released an annual report, at least up until 1920 (as that is where the record ends on HathiTrust) in accordance with their custom and in compliance with the directions of their charter (Annual Report for the year 1897).

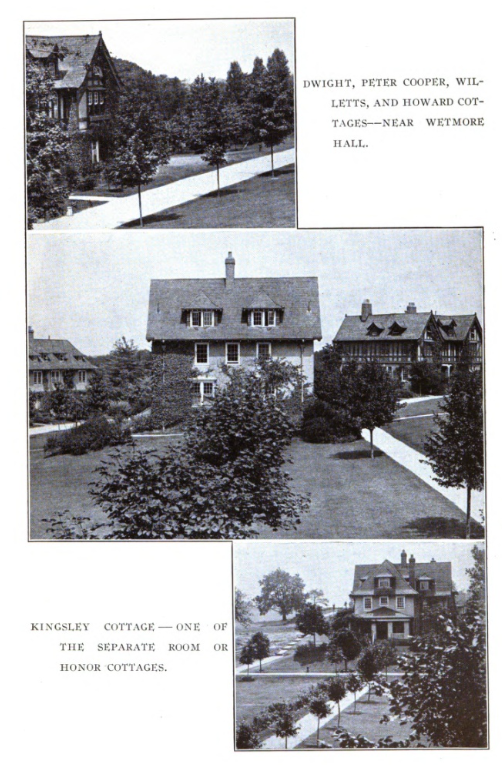

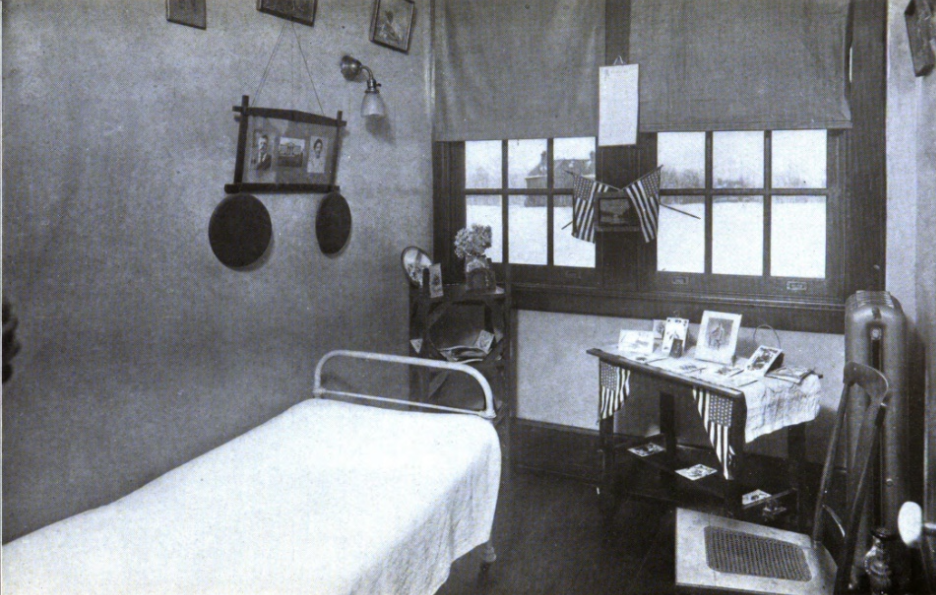

In 1919, by order of the Supreme Court of New York and upon the petition of the Directors, the corporate title of the New York Juvenile Asylum was changed to the name, which for many years had been unofficially used, and the institution became the Children’s Village (Annual Report for the Year 1920). The change in name reflects the shift in locations and organization over the years. In 1897, a committee on plan and scope determined that the asylum should substitute the Cottage System for the current Barrack System. With this change came the authorization to sell the property in Washington Heights for a better location for cottages (Annual Report for the year 1897). This shift to the Cottage System reflects the values of the reformatory plan popular for institutions for delinquent children, as explained by Platt (2009). The cottage system reflected more individualized care, as well as the pure rural ideal.

Annual Report from the year 1918

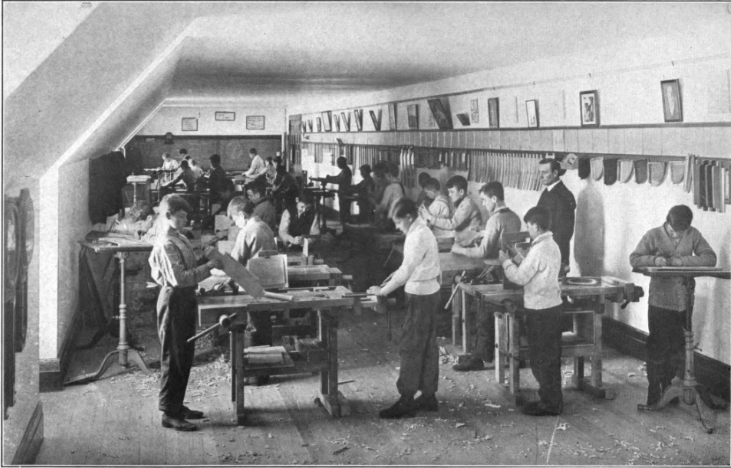

The New York Juvenile Asylum receives the wayward and delinquent boys committed to it by the Children’s Courts. Within the institution, children receive education: girls domestic training, and boys vocational training (Annual Report for the year 1897). Children live at the asylum while receiving education and general care. There is an emphasis from the directors in the reports for the reformation of “destitute” children.

Part of the New York Juvenile Asylum was the Western Agency. The Illinois Children’s Home and Aid Society, of Chicago, acting as the agent of the Asylum, secured homes in the middle west for children deemed to require permanent guardianship and a complete change of location: of placing and supervising the children in their replacement or the maturity of indenture (Annual report for the year 1905).

As a Child May Move Through Institutions of the Justice System

Who and How?

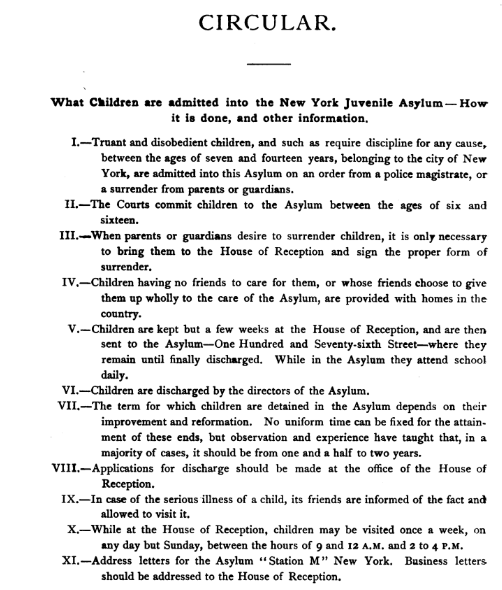

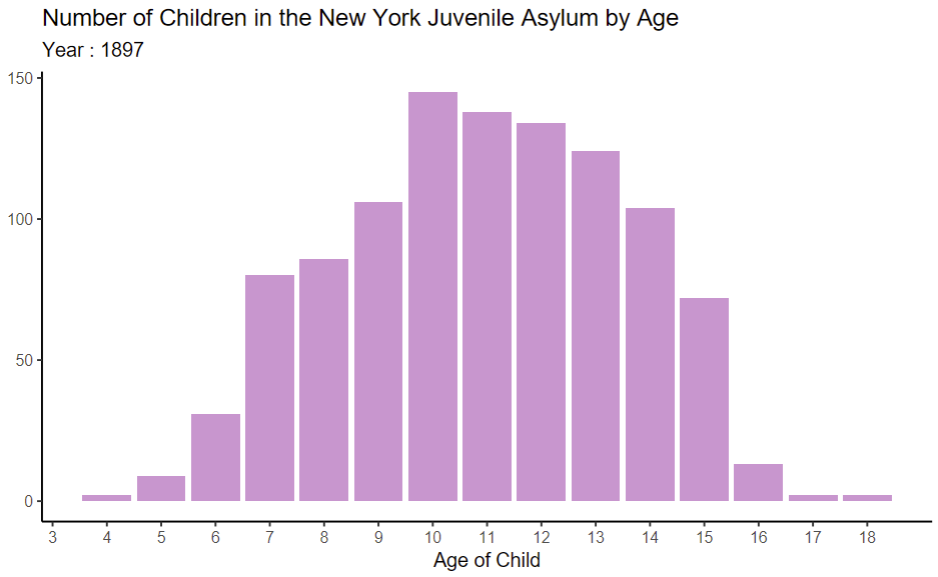

The Children committed to the Children’s Village include both delinquent and dependent children. Delinquent children ages 6-16 were sentenced by the courts, while dependent children may have been sent there by the court or surrendered by guardians.

(Annual Report for the Year 1897)

Data sourced from Hathi Trust from the Annual report of the Children’s Village to the legislature of the State and to the Board of Aldermen of the City of New York for the year 1897

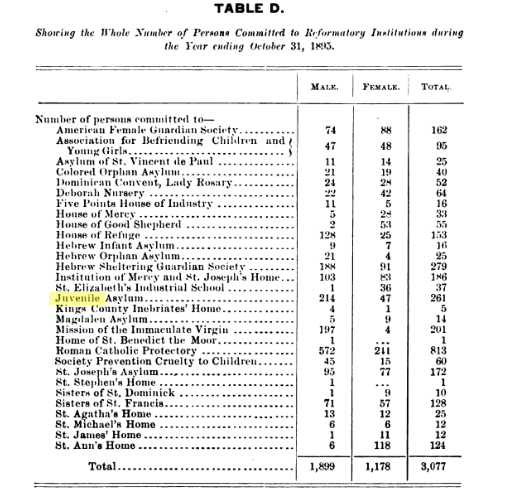

In addition to the Children’s Court, the standard district courts of New York committed children to the Children’s Village. In the year 1895, it was reported in the Annual report of the Board of City Magistrates of the City of New York that 261 children were committed to the “Juvenile Asylum.”

(Annual Report of the Board of City Magistrates of the City of New York 1895)

Racial Composition

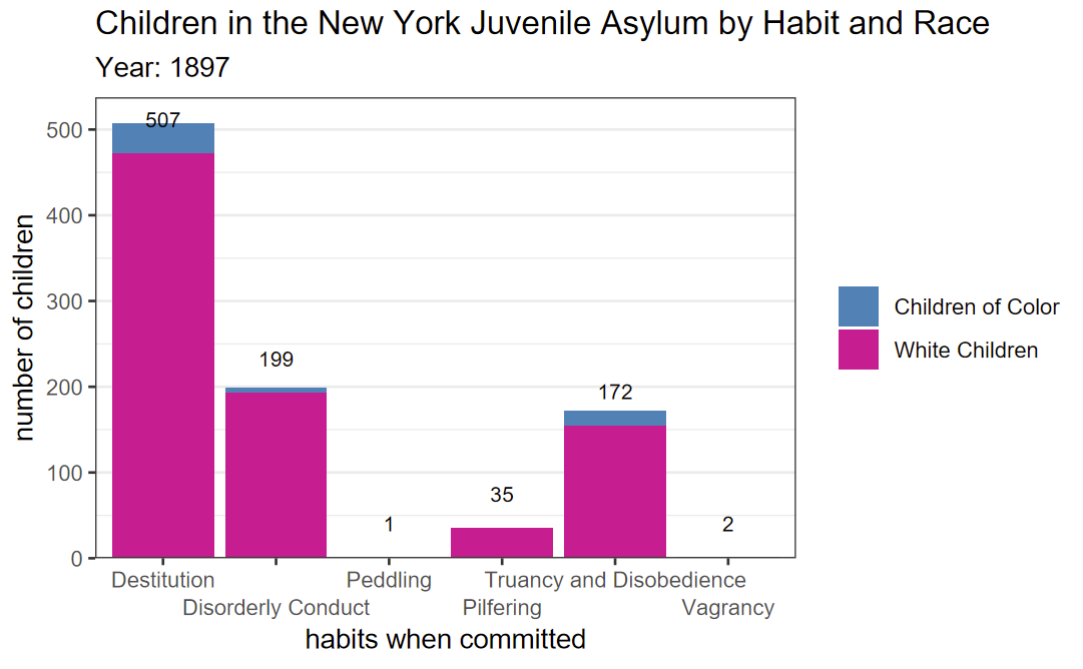

There were significant discrepancies in the proportional representation of Black children as juvenile delinquents compared to White children. The Annual Reports of the New York Children’s Juvenile Asylum included much data, some of which broken up by race. One instance of data provided that is specifically related to delinquency and is broken up by race is the delinquent habits of children. The report for the year 1897 reports the number of children with delinquent “habits when committed” and breaks this data up both race and gender. Aiming to see the progression of the institution, the report for the year 1920 reports the “causes of commitment” and breaks this data up by race.

1897

Data sourced from Hathi Trust from the Annual report of the Children’s Village to the legislature of the State and to the Board of Aldermen of the City of New York for the year 1897

The chart shows that there is a much larger representation of white children for each habit, and thus overall. The data reflects that 6.4% of the children in the Children’s Village reported to have these habits were children of color.

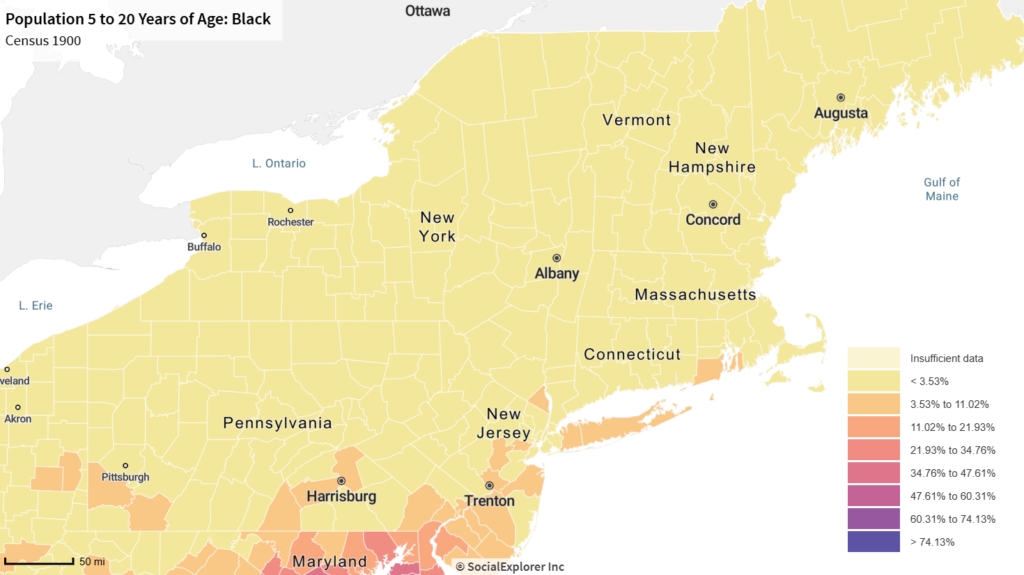

The map below shows the proportion of the population from ages 5 to 20 that is black in the northeast for the year 1900. 1900 is the closest year in the census record to 1897.

Looking at the map, we can see that the proportion of the population from ages 5 to 20 is below 3.5% for New York county, which is where the Children’s Village was located, as well as the Children’s Court and city magistrates that were responsible for much of the committals. The demographic data thus suggests that children of color are overrepresented in the Children’s Village for the year 1897.

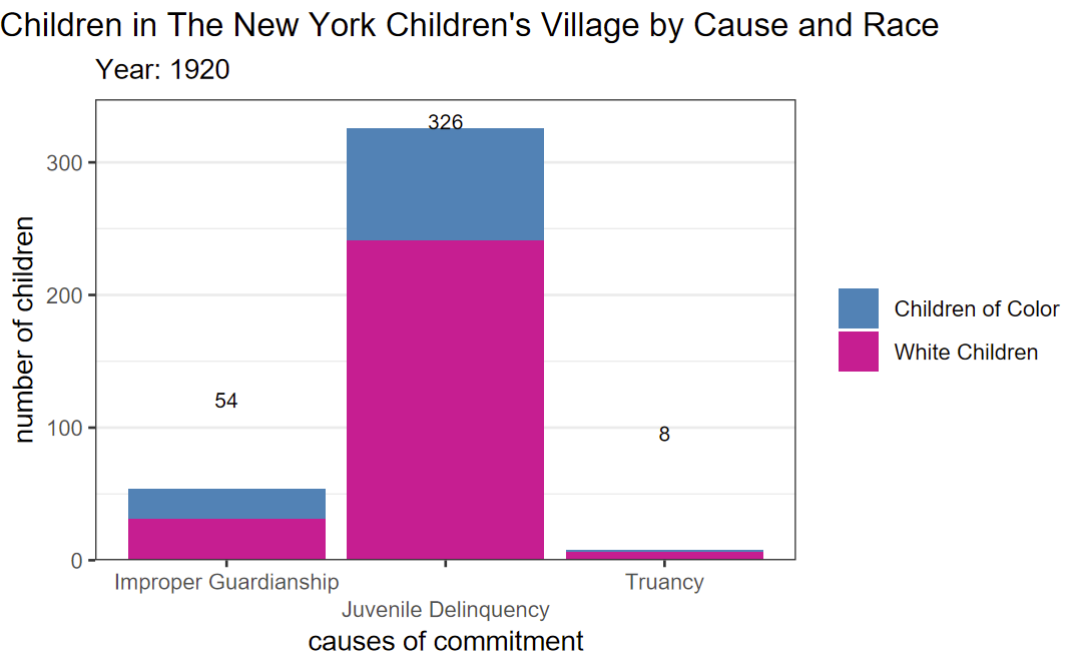

1920

Data sourced from Hathi Trust from the Annual report of the Children’s Village to the legislature of the State and to the Board of Aldermen of the City of New York for the year 1920

The chart shows that there is a larger representation of white children for each habit, and thus overall. The data reflects that 28.7% of the children in the Children’s Village reported to have these habits were children of color.

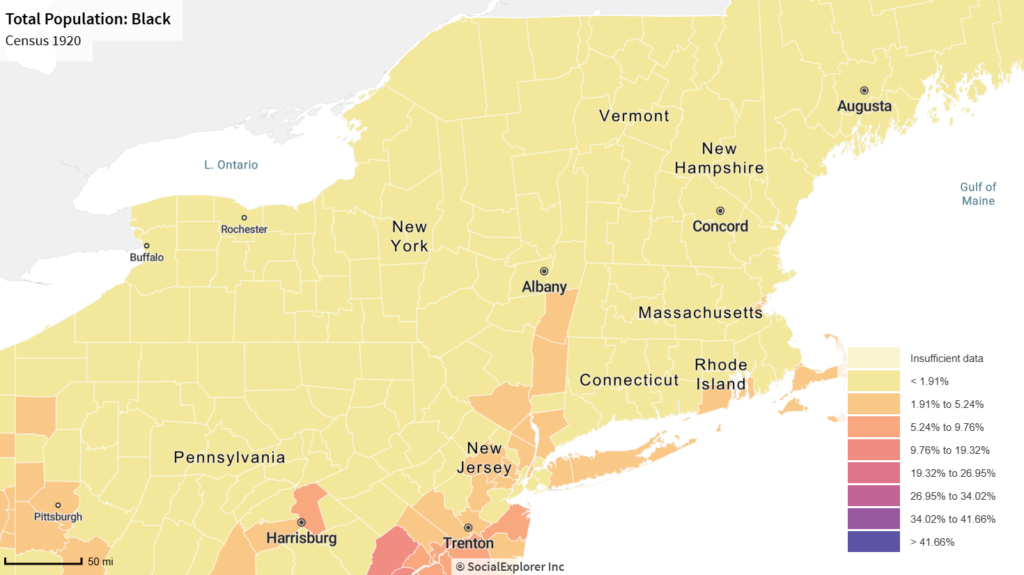

The map below shows the proportion of the total population that is black in the northeast for the year 1920.

Looking at the map, we can see that the proportion of the total population that is black is below 1.91% for New York county. Looking in the surrounding areas, the proportion of the total population that is black is at least below 9.76%. The demographic data thus suggests that children of color are significantly overrepresented in the Children’s Village for the year 1920.

The percentage of children of color represented as delinquents in the Children’s Village increases from 1897 to 1920, while the percentage of children of color in the greater population of New York decreases, thus the overrepresentation of children of color in the Children’s Village increases. It should be noted that we do not have a perfect comparison as the 1900 census data shows us the population of people ages 5 to 20, while the 1920 census data shows us the total population. Furthermore, the classifications for delinquent behavior differ from the 1897 report of the Children’s Village to the 1920 report of the Children’s Village, however these discrepancies are comparable enough that the comparison is significant. It should also be noted that the Children’s Village breaks data up by white children and “colored children,” while the census data shows us the proportion of the population that is black. It is uncertain what races and/or ethnicities are represented by the label “colored.” This may lead to an overinflation of our accounts of recognizing the overrepresentation of children of color. Nevertheless, the data we have at hand provides significant insight into the proportional representation of children by race.

So, what accounts for such a large racial discrepancy? There are a number of reasons. One reason for the discrepancy may be prejudice that the actors within the justice system hold. As Platt (2009) explains, the regulating of juvenile delinquency requires a degree of discretion on the part of enforcers. He also explains that Darwinism and eugenics were popularly bought into at the time. This would lead to children of color being labeled as delinquent at a greater rate than white children, be it by the police that pick-up children off the street, or court judges that label children as delinquent rather than dependent. Another reason may be that non-white families were poorer than white families. Bush (2018) showed that there was a greater intervention of the state into the lives of poor families. This was shaped from a view that delinquent children were a product of inadequate parenting. Poor families could not afford to provide for their children in the same way that middle- and upper-class families could, thus not meeting the standards of the middle- and upper- class child savers that ran the justice system. This would lead to a greater intervention into the lives of non-white families, as they were more likely to be poor than white families due to systematic racism that impacts educational and work opportunities. Another possibility may be the lack of institutional opportunities for dependent black children. Agyepong (2018) extensively discusses that formal or informal segregation and racial bias led to a dearth of resources for black communities. This racial bias and segregation were much less prominent in institutions for delinquent children. Black dependent children, as a result, were sent to institutions for delinquent children in order for them to have access to institutional care in some form. Regardless of the reason, it is clear that children of color were disproportionately represented by the juvenile delinquent label.