Home | Introduction | Literature Review | Data and Analysis | Conclusion |References

Power and control

Children learn the importance of a well balanced diet, as well as the importance of “Eat[ing] the Right Food”. Eleven Mile Corner, AZ (Lee, R., photographer. 1942.)

The local perspectives on migrant families portrays many aspects of power and control, both societally and federally. Sidney Baldwin notes pushback from local communities during the installation of Farm Workers’ Communities, with local citizens in New Jersey claiming “the project would attract a ‘low class of people’” (Baldwin, 1968, p. 112) and that the federal government was usurping the power of the states with their “un-American” and “communist” efforts. The struggle for power and control occurred not only within the camp environment, but also between local and federal legislation and ultimately shaped the general successes of the program. The conflict between state and federal interests ultimately created many varying situations in which the struggle for power and control affected migrants involved in Farm Workers’ Communities.

One way in which migrant families attempted to distance themselves from the control of the local and federal governments is through the maintaining of cultural practices. Agnes Meyer, journalist for The Texas Spectator notes that many migrant Mexican women in Farm Workers’ Communities opted for the paid, traditional services of a curandera, a native healer, when dealing with medical issues within their families as opposed to the free services of the camp medical clinic (Meyer, 1946). Although this practice sometimes ended in tragedy due to a lack of western medicine, this practice highlights the cultural diversity of the camps and traditional Mexican lifestyle choices that were intended to have been phased out in the federal attempt to assimilate Mexican migrants. In light of this however, comes statistics involving successful and healthy births that occurred within the camps. In year one of the medical service plan, 18 spanish women who had previously either never had a physician at birth or had lost babies prior, had “healthy FSA Medical Services babies” with the help of camp medical services (Grey, 1999, p. 86), and 31 cases total in which no infant deaths occurred. The structure of camp programs pushed other national ideals of health, as well, in the form of nutrition education. The image above portrays health education classes regarding proper nutrition. However, subtly embedded in nutrition curriculum are conceptions of, and the reinforcement of, American ideals. The poster on the blackboard implores kids to “Eat the Right Food”, specifically, American ideals of the ‘right’ food, such as enriched brown cereals. Although nutrition education is beneficial to the health of growing children and the construction of familial livelihoods, the imposing American ideals of what food specifically are ‘right’ for the family to consume reinforces the idea that culturally differing standards of diet and mealtime can be construed as ‘wrong’. Further, as seen on the blackboard, these enriched brown cereals aid in the completion of “efficient work”, pushing the ideal on to children that a working American is a healthy American. In discussing aspects of power and control within the camps, the close quarters of the community held its own advantages and disadvantages. Socially, pressures to conform also existed among residents, reinforced by the structure of the camps. Pat Rush, a young resident of Weedpatch Farm Workers’ Community in the 1940s, notes that “If your rent was late, they would get on the loudspeaker and they would say your name, and the whole camp could hear” (Summers, 2024, 8:56-9:05) this is one of the many examples of how scrutiny from other residents within the camps may have arisen due to publicized methods of communicating to residents that they had misstepped with their duties as members of the community.

Race and class

“Despite recalling the segregated living quarters, [a resident] remembered that black and Hispanic residents interacted with each other in meaningful ways, sharing butter, cornbread, and molasses. Another respondent, the son of one of the camp managers, also remembered African American and Hispanic residents playing baseball together.” (Robbins and Robbins, 2015, p. 261)

In studying the effects of racial discrimination and discrimination based on class, some of the most useful data sets are those of qualitative and personal accounts from persons affected. Housing within the camps were segregated both by race and class, with differing housing situations according to placement. Pedro Maldonado, previous resident at Robstown FSA camp notes that there were “special quarters for black people . . . like Quonset metal huts” that were incredibly hot to live in during the summertime (Robbins and Robbins, 2015, p. 256). Further, resident Jim Elliff, son of a camp manager, notes that he himself lived in one of the permanent housing units separate from the migrant laborer tents. The division between expectations of housing provides insight into subtle instances of discrimination, such as segregation of housing and the varying qualities each settlement held.

In terms of education for migrant children, discrimination was also seen within local school systems. In a 1934 study of Mexican-American children in Nueces County, Texas, near Robstown FSA camp, it was found that racial discrimination was not only embedded in local attitudes, but also in state school systems. Through interviews with two town superintendents of the county, researcher Paul Taylor discovered that “Most of the schools take money out of the [federal] Mexican allotment and use it for whites” (Taylor, 1943, p. 200) and that the school term for Mexican-American children is not only started later, but also stopped a month early for migrant Mexican children to return to the fields for cotton season. These anecdotes further exemplify the systemic racism towards migrant children of Mexican descent, and solidify that access to education was not only limited by childrens’ willingness to attend school due to racism, but by institutional barriers. The shortening of the school year for cotton-picking highlights the discriminatory societal ideal that Mexicans are to be held to higher standards for labor, and are thus held to lower standards of education.

Further qualitative evidence reveals discrimination towards migrant children due to class. Robstown camp manager, Henry Daniels, reported that

“The [camp] children had not been in school for the last few years, and most of them did not rise above the third grade. […] Most of them evince no great desire to return to school, their chief objection being their economic, social, or racial status.” (1940 Robstown Files Archive, as cited in Martínez-Matsuda, 2009, p. 285)

Goldie Farris, an adolescent girl who stayed for a brief time at Brawley FSA camp in California, notes

“As far as the town and the community was concerned it was a real stigma to have lived there…. I was very careful in Brawley. I had learned from experience you don’t tell everything so I didn’t tell any of the students or anybody in my class where I was from or where I lived” (Cannon, 1996, p. 18).

Pat Rush, another young girl at Weedpatch FSA camp, recalls her experience traveling to the nearby town of Lamont:

“We probably stood out like a sore thumb […] the business owners were California people and I didn’t feel like they wanted us here. And I would see them kind of snickering at us because we talked different, maybe dressed a little different. […] I think they thought we were lower class people, maybe dirty.” (Summers, 2024, 9:56-10:20)

The discrimination against migrant students of any race is visible in the attitudes of both local legislators as well as local children and families. Daniels also notes, however, that program managers recognized this as a severe problem, ultimately providing extra support in the form of school clothing grants, donating school lunches, and providing transportation when buses either could not or would not stop at the camp for student pick up. Combined with efforts within the camps, school attendance rose among children from many camps, increasing the ability for camp children to receive an education (Martínez-Matsuda, 2009, p. 286).

Constructions of an Ideal, American Childhood

1941 National Survey Statistics – Farm Workers’ Communities / Migratory Labor Camps

| Total members across 53 Communities | Members aged 19 or younger | Members between the ages of 5 and 14 | Members under 5 years old | % of total members aged 0 to 14 | % of total members aged 0 through 19 |

| 68,700 | 30,700 | 15,400 | 9,200 | ~36% | ~80% |

Pat Rush, a young resident of Weedpatch Farm Workers’ Community in the 1940s came from Arkansas, and remembers her role at the camp as caretaker of her younger sister.

“Everybody was working in the fields, my mother, my sisters, and my brother, […] but my job was to stay home and take care of my baby sister. I must’ve been 11, I’m not sure. I was just at the right age to stay home, and do kind of what little women do. Clean the cabins, [I] learned to make cornbread, it was kind of like playing house.”

Rush recalls her time at the Farm Workers’ Community primarily through the lens of the family caretaker, tasked with cleaning the house, cooking meals, and caring for the children. This rejects the growing American construction of the ideal childhood, where childhood is protected and sacred. Rush’s experience highlights a gendered construction of the home overlapping with childhood expectations, ultimately overtaking them. Rush further notes how she felt like she was “playing house,” making a game out of her responsibilities to make the best of them. In further recognizing the gendered expectations of children in the camps, Martínez-Matsuda notes that FSA camps also focused their efforts in the construction of the ideal American childhood, family, and family structure on young Mexican girls through Home Management training. Women in the position of “Home Management Supervisor” were tasked with teaching young Mexican girls proper money management, relationship advice, and how to upkeep a happy and healthy home. Similarly, at Harlingen camp in Texas, the “Sunshine Health Club” taught girls aged 6 to 16 proper domestic duties, ultimately promoting the middle-class American ideals of proper female behavior in the home, engaging culturally Mexican children in Western techniques of “proper” child rearing and indirectly confining women’s familial contributions to the domestic sphere (Martínez-Matsuda, 2009, p. 225). Beyond just gendered expectations of children, lived experiences of childhood differed between races, as well. Mexican migrants’ memories of the towns surrounding the Farm Workers’ Communities are also embedded within the spatial realities of segregation. In Texas, most public pools were segregated, and did not admit Mexican families. Herón Ramírez, resident at the Robstown Farm Workers’ Community and interviewed by Martínez-Matsuda, notes that on a trip to the public pool with his white friends in the camp:

“I had to wait for them outside the fence, while their family had their fun jumping around, because I couldn’t go in.”

Despite the federal pressure to educate children, supply childcare services, and allow them access to town amenities, this was not always the case, as seen with Pat Rush’s experience at Weedpatch and Ramírez’s experience at Robstown. Martínez-Matsuda highlights that by 1943, the program had lost most of its funding, and by the late 1940s, few camps had the same amenities that had initially aided child migrants: nursery schools, home demonstration workshops, and camp committees (Martínez-Matsuda, 2009, p. 150). The decline of these amenities implies a shift from a family-oriented community to that of a simple, low-cost housing environment for adult laborers. However, as seen in the table above, about 80% of residents at the communities were between the ages of 0 and 19 in 1941, and about 36% were aged 0 to 14. As quoted in Michael Grey’s 1999 book, journalist Carey Williams notes that “children were essential breadwinners for many migrant families, and often only attended school when it did not interfere with crop harvesting” (Grey, 1999, p. 29). In poorer, farming families, education often came secondary to the harvest, and due to the low amount of income made from each harvest, families needed all the hands they could get to make enough money to get by, even in federally funded environments. Below is a StoryMap displaying residential children at various Farm Workers’ Communities, and the constructions of childhood embedded in their experiences.

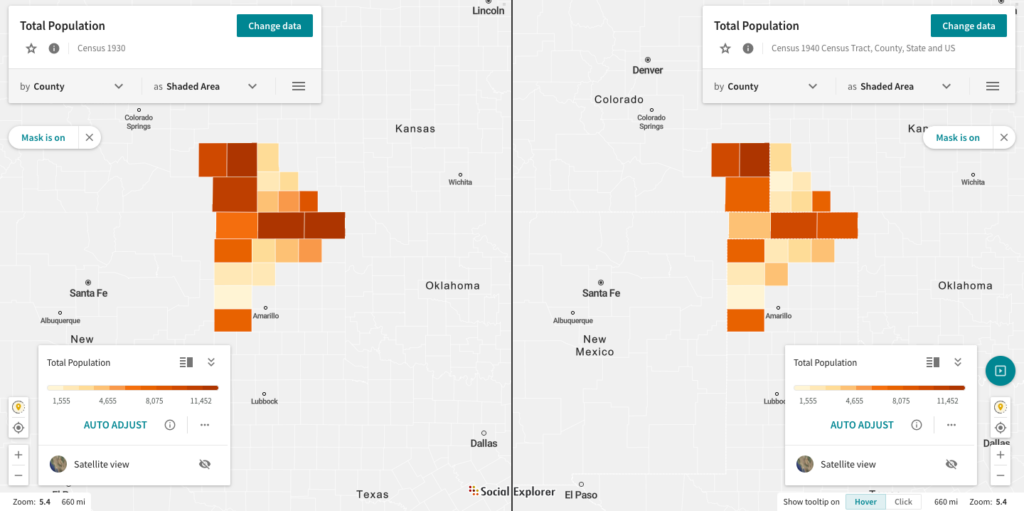

Social Explorer Maps – 20 Counties most affected by Dust Bowl conditions

LEFT: 1930 Total Population RIGHT: 1940 Total Population

Original Dust Bowl County information from the National Bureau of Economic Research, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service (SCS) as cited in Long and Siu, 2016