Doll play as a representation of societal values:

One of the most common themes in modern scholarship about dolls and play is the shifting relationships between play and real life. Many scholars examine the specific ways that play can be influenced by children’s experiences as well as broader societal norms. This research forms the basis for deeper research on how topics like race, gender, and beauty relate to children’s play.

Children naturally mimic the values and actions of the people around them. Dolls provide an easy outlet to practice ideas of beauty, love, and fairness. As children grow and experience new things, they use play as a way to test and modify the cultural attitudes that are shown to them. Thomas (2005a) examines the ways that racial prejudice was expressed through white children’s doll play. The chapter uses a set of interviews about black dolls that was conducted with white women born between 1884 and 1928. Some women thought of their black dolls as special and were proud of them, though the pride was often specifically because the dolls were unusual and others disliked them. Other women expressed shame about being seen with black dolls in public. Through play, the women expressed common ideas about black people such as exoticism and fear. Thomas also analyzes Hall and Ellis’ A Study of Dolls, which was published in 1897. The study found that some children thought of their black dolls as unclean and inferior to their other dolls. One child in their study was so terrified of her black doll that she burned it in the fireplace, then was terrified of its ghost for weeks. The two studies that Thomas examined show the different ways that racial stereotypes made their way into white children’s play.

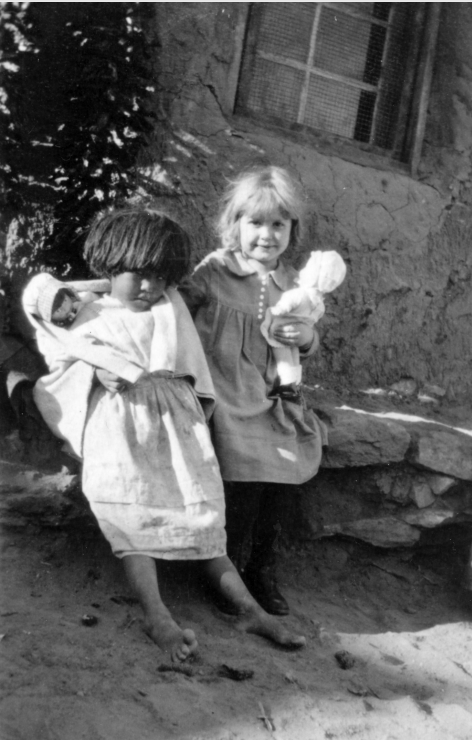

at the Hopi Village, January 1926.”

In Jacobs (2008)

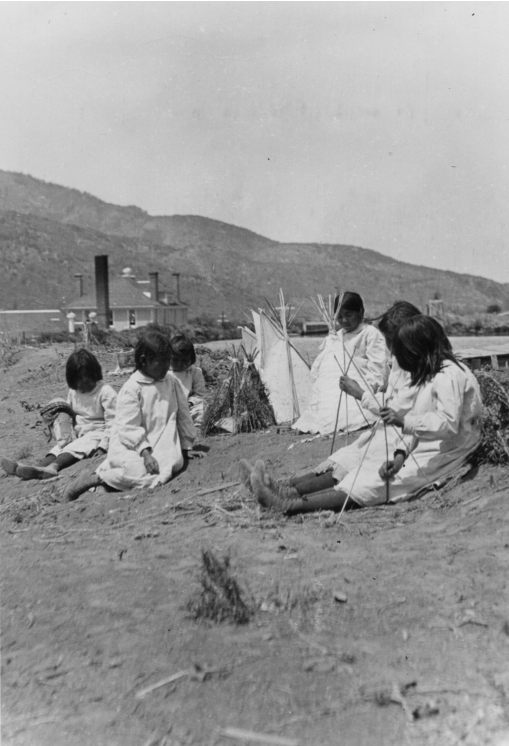

and wickiups with a frame wooden structure

in the background.” In Jacobs (2008)

Jacobs (2008) uses a more theoretical approach to examine what Bernstein (2011) refers to as “the terrifying instability between people and things.” The article uses three photographs of Native American girls in the early 20th century to explore how children’s actual behavior compared to the values they were shown. The first two photos (above) show children playing with their dolls in ways that reflect the culture they were born into. In one photo, a Hopi girl carries her doll tied across her back. In the other, a group of Mescalero girls build miniature teepees for their dolls. As Jacobs writes, these children reflect the idea that doll play is highly representative of children’s real lives. The third photo (below) shows a group of girls at the Santa Fe Indian School posing for a photo while cradling their baby dolls. The dolls all have white skin and are dressed in European-style clothing. Jacobs argues that this is not simply a case of the girls performing the narratives that went along with white dolls, but rather an example of children using dolls as a way to navigate competing identities and social expectations. Jacobs’ analysis complicates the relationships between doll and self, showing how children can both influence and be influenced by the narratives of their dolls.

Racialized Dolls in the Mass Market

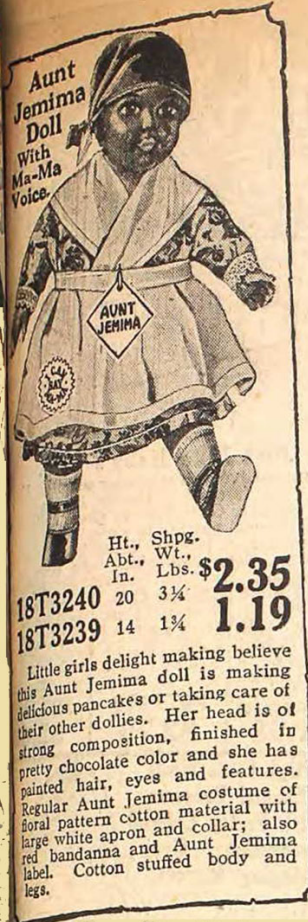

The marketing and design of racialized dolls reinforced many common racist stereotypes. Many of the dolls were marketed after characters that were popular in media at the time, particularly minstrel shows. The dolls took the already racist practices and brought them to a larger, more impressionable market (Bernstein, 2011). Wilkinson (1987) provides a broad overview of the naming and design of several popular dolls that were modeled after racist caricatures. The article focuses specifically on the “Mammy”, “Darkey”, and “Aunt Jemima” characters. These characters reinforced common views about race and gender, particularly the idea that black women should act as servants to white families. The dolls were often designed to be inaccurate and exaggerated representations of how black people actually looked and dressed. Their appearance was so dramatic that some psychologists recommended against giving them to children because they could cause nightmares.

Wilkinson (1987) and Martin (2014) both address the way that racialized dolls were advertised to white children. Wilkinson focuses on the language used, providing examples of the way that racial slurs and differences in dialogue style were used in advertising to create a negative image of the dolls, and by extension, the people they were modeled after. Martin uses qualitative and quantitative analysis of several historical toy catalogs to discuss the way that dolls of different races were marketed. By comparing the language used to advertise dark-skinned dolls with that of white dolls, the article highlights the stark difference in society’s perception of the two groups. Martin finds that dolls with dark skin generally had descriptions that were much more focused on their utility and were often named after common stereotyped characters, while white dolls’ descriptions focused much more on beauty and femininity. The article also includes qualitative data on the number and percentage of black dolls that were advertised in catalogs through time. Martin observes that Sears, one of the largest doll producers in the country in the 1920s, didn’t stock its first black doll until 1912. He also finds that 76% of the black dolls the company sold between 1912 and 1937 involved themes and caricatures from the southern Antebellum era. This observation highlights the role that socioeconomic status had in doll play, reinforcing strict societal roles and economic inequality.

These biases in the construction and marketing of dolls created a difference in the stories that were being presented to black and white children. Bernstein (2011) describes how the characters represented by black dolls were almost always in positions of servitude. Many books instructing children on how to make their own dolls also encouraged making black dolls specifically to function as servants or maids. Violence was another common narrative for black dolls, with some books encouraging children to wipe their pen on the doll’s skirt or use its body as a pincushion in a way that is eerily similar to the idea of “voodoo dolls” that became popular in later years. In these ways, the design and marketing of black dolls in the early 20th century shaped children’s play with dolls, which in turn shaped their perceptions of themselves and the people around them.

Rise of Non-Stereotyped Dolls

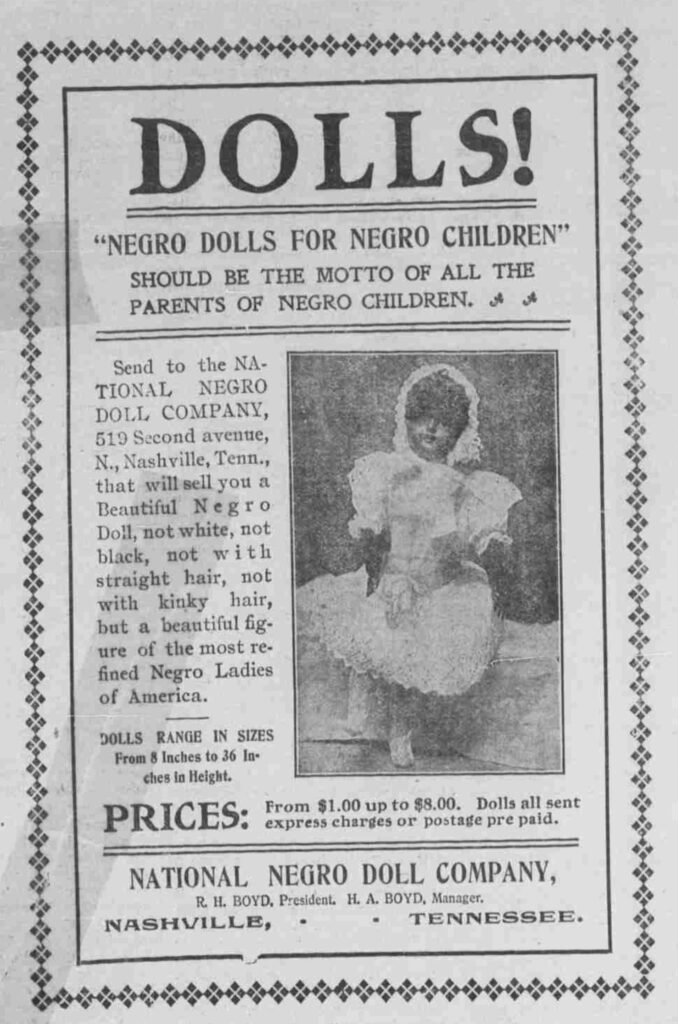

Activists as early as the 1850s recognized the importance of black children having accurate representation (Thomas, 2005b). The problem became even more evident as consumerism increased through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the start of the 20th century, many activists and scholars were beginning to call out the stereotyped narratives that were pushed by popular toy companies. Recognition of the harm these narratives caused led to an increasing demand for non-stereotyped black dolls. Black parents began to notice that their children were rejecting the derogatory caricatures that were common, and writers and activists latched onto the black doll as a symbol of racial equality and progress (Bernstein, 2011). The founding of the National Negro Doll Company in 1909 represented an important step towards equal representation. While their dolls still conformed somewhat to white beauty standards, the company’s focus on black dolls by and for black people made them extremely popular. The Universal Negro Improvement Association’s doll company, founded in the 1920s, attempted to improve on previous developments. They prided themselves on creating dolls with darker skin that were untouched by white ideals of beauty (Thomas, 2005b). While neither brand of new doll was perfect, they were a massive improvement from the black dolls available from mainstream toy companies. Bernstein (2011) discusses how the design and marketing of the new black dolls differed from mass market dolls. Advertising for the new black dolls emphasized beauty and placed the dolls exclusively in family roles rather than servitude. Many of the new dolls were also intentionally very fragile, forcing children to be kind and gentle with them. This was very different from the durability of many stereotyped dolls, which presented a narrative of black people being less fragile and worthy of care. By manufacturing beautiful, accurate dolls, activists hoped to rewrite the narratives that other dolls had pushed so forcefully onto their children.

December 17 1909, from The Library of Congress