Boys Summer Camps of the Northeastern United States

Introduction | Literature Review| Data and Analysis | Conclusion| Sources | Storymap

Summer camp is a pervasive cultural icon of American childhood. Harvard president Charles Eliot called summer camps “the most important step in education that America has given the world” (Maynard 1999, p. 3). Summer camps emerged simultaneously with the cultural progression of children from valuable working family members, to precious gifts entitled to education and a childhood. As compulsory schooling laws, and anti-child labor laws kept children in school and out of work, there was a growing need for summer activities for middle class urban children (Paris 2008). The traditional American summer camp was conceived as a refuge in nature where children could spend their days happily connecting with the wild. Summer camps provided rustic cabins tucked away in the wild, days spent swimming in the lake and nights spent singing around the campfire. In order to understand the origins of summer camps, we must examine social fears of the late 19th century surrounding urbanization, industrialization, and immigration.

Nature: A Cure to City Evils

While examining the Boy Scouts’ conservation of nature, Ben Jordan (2010) explains why nature was so tied to masculinity. At the turn of the 20th century, American society had basically transitioned from wild and rugged westward expansion to industrial urbanization. A change in philosophy emerged as a reaction. Victorian Era philosophy was that boys needed to conserve their bodily fluids by not masturbating or physically exerting themselves so that they would develop into self-controlled, civilized young men capable of success in the industrial capitalist economy (Jordan 2010, p. 616). At the turn of 20th century, “‘closing of the frontier,’ rapid urbanization, corporate bureaucratization, the ‘New Woman,’ the ‘New Negro,’ and ‘new immigrants’ from southern and eastern Europe challenged native born white mens authority” (Jordan 2010, p. 616). This caused a crisis of masculinity, and native born white men challenged Victorian philosophy as feminine, passive, and over-civilized. They turned to the outdoors “as a surrogate for the rugged individualism of American pioneers and Indian mythology and for passing modes of pre-industrial labor” (Jordan 2010, p. 616). The city was seen as causing lazy and weak men, and also causing crime and bad morals. In this way, summer camps emerged along with the “back to nature” movement. This train of thought fits right into the 19th century fears about urban physical and moral pollutants. Early summer camp advocates had the same Progressive Era thinking as Child Savers and Playground Association of America (Smith 2006, p. 76). Like the Child Savers, summer camps were a place to separate children from the city, and like the PAA, camps were a heavily symbolic and supervised space set to influence children’s growth and moral development. Summer camps separated boys physically from the city, and transported them to the wilderness where they could grow into manly men. While the city creates lazy boys, nature allows boys to express and work through their wild side. Summer camps, like most children’s institutions of the time, were heavily influenced by the psychological theories of G. Stanley Hall’s Adolescence from 1904 (Smith 2006, Jordan 2010). Hall proposed a theory of recapitulation, in which children must progress through all prior human evolutionary stages before reaching the modern man. In other words, children have a primal phase, a tribal phase, and so forth until they reach civilized modern manhood (Smith 2006, Jordan 2010). Hall warned that children’s tribal phase should not happen in the city, or it would lead to crime and gangs (Smith 2006, Jordan 2010).

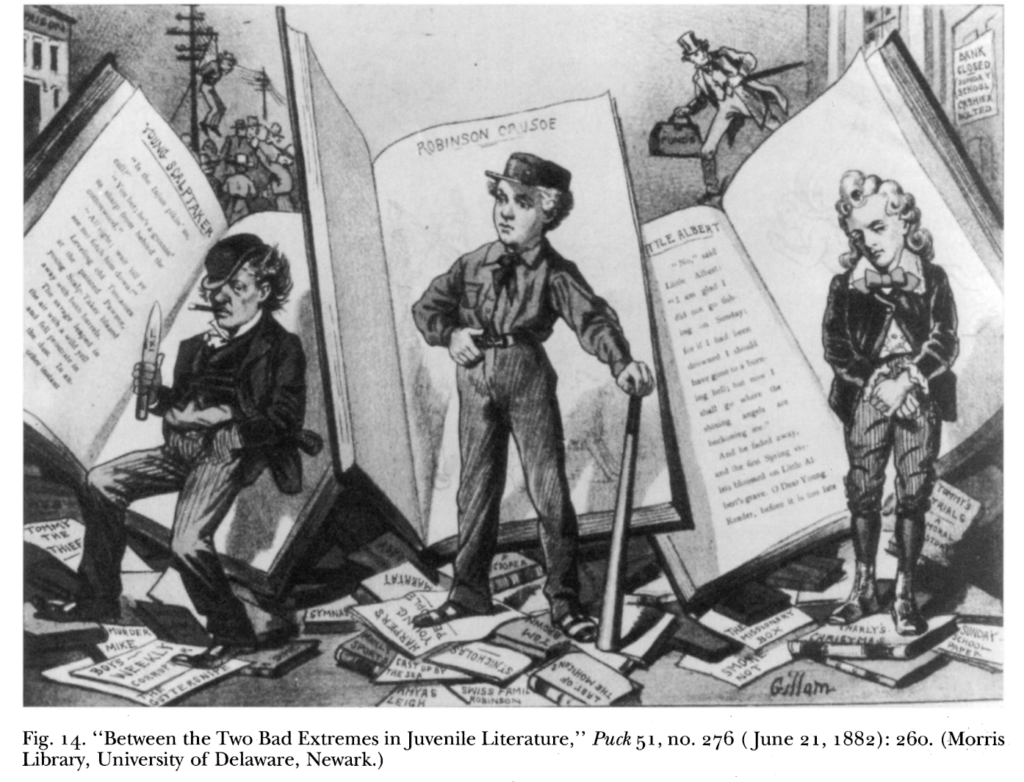

As seen in the image above, boys were expected to exist between two extremes; a ruffian and a proper gentlemen. They were to pass through the more primal phases, and keep the good parts without becoming to lazy and spoiled. Summer camps were adequately equipped to foster this “tribal or savage phase” in children, by introducing them to nature, playing sports, and building camaraderie or a tribe. In her study of gendered spaces in the Boy Scouts of America, Samantha Pentecost (2020) identifies that the outdoors was viewed as where a boy becomes a man. In this way, the origin of summer camps is gendered. Like many spaces, summer camps engage in gendered practices, and are social reproductions of gender (Pentecost 2020). How then, do summer camps and BSA camps that were created closely with masculinity in mind fit girls into their curriculum? This has implications for girls joining the boy scouts starting in 2019.

Adults Shape the Space

Although camp advocates describe camps as natural, and isolated from modern society, they are imbued with the social values and anxieties of adults. As Jim Rasenberger (2008) puts it, “camp is a lifestyle choice,” and adults send children to camps they believe will benefit them (Rasenberger 2008, p. 24). These remote camps —while physically distant from society—are not natural, they are manufactured for the purpose of raising modern men. A camp’s manufactured nature becomes apparent when observing its living structures, surrounding natural phenomena, and daily activities.

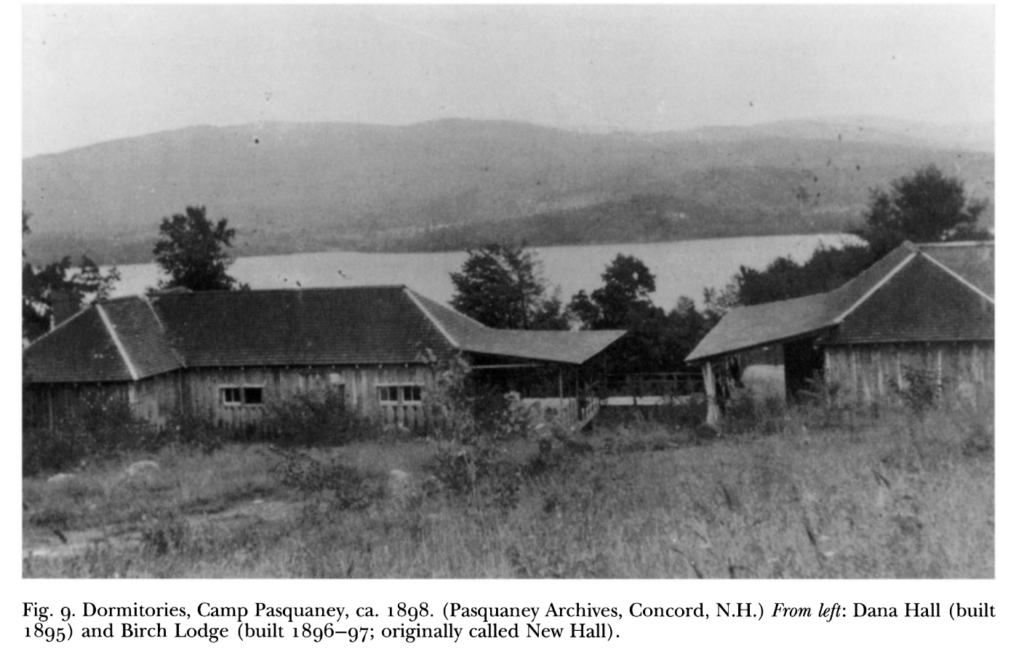

The buildings are an “‘intermediate structure’ between the man-made and the natural in fulfillment of the goals of the rustic” (Maynard 1999, p. 15). The housing is sparse, normally wood shelters, to give a rugged feel, but without any real hardship. Camps had to strike a delicate balance between wild and homely, because they needed to attract prospective campers who were rich children used to some level of comfort (Maynard 1999, p. 21). Summer camps emphasize the primal features of youth according to G. Stanley Hall, but they also prepared youth for collaboration and leadership through social activities, such as cabin teams and athletic activities. Children were quickly taught there was a camp hierarchy in place, with adults and counselors at the top, then returning campers, and finally new campers. Each year, returning campers would be excited to show off their prior knowledge of camp rituals, including hazing. Camps had a hearth where boys would gather around in brotherhood to sing songs. This is one example of how camps commonly cosplayed Native American traditions. Racial play in camps was seen as a way for children to experiment with their “tribal phase” while being supervised by camp authorities. Leslie Paris writes in her book how “white campers explored the world of supervised, corporeal darkness in casual ways including summer tans, Indian war cries, and racial slurs, as well as in organized community performance” (Paris 2008, p. 193). The “organized community performance[s]” Paris refers to are summer camp plays, including minstrel shows and false Indian Lore. These plays aligned with recapitulation theory, but they also served to place Native American and black people in the past by treating their experiences as historical fiction.

Were These Camps Effective in their Goals?

Was learning how to use an ax, or pitch a tent, really a productive way to instill in young men the skills they need to thrive in industrial American society? Smith (2006) writes that nature is not the root of what makes traditional American summer camps effective, rather it is the contrast between their daily bustling city life and their natural camp life. While summer camps advocate their retreats as a place campers can experience “real living,” most campers viewed their fleeting summer retreats as the less natural of the two. Summer camps, with their mixture of communal living, nostalgia for the past, “Indian lore,” and strict structure, were quite different from children’s daily lives (Smith 2006, p. 87). Smith introduces this divide as Fritz Redl’s “‘Ego Ideal of the Good Camper,’ a normative construction cobbled together from mythology and social expectations that could be a ‘psychopathological risk’ for children” (Smith 2006, p. 87). Children were expected to adapt temporarily to the camp world but also preserve the traits necessary for success in the real world, which could cause psychological distress. There is a divide between what summer camp advocates imposed on children, and their realities. While this can be confusing and hard for children, they also use this contrast to experience friendship, love, fear, smells, and hardships without distraction. They clarify their values and test which ones are worth bringing back with them (Smith 2006, p. 94). While the physical camp experiences might fade, the memories stay with the youths, and they return home with a new character and sense of pride and accomplishment (Rasenberger 2008).