Boys Summer Camps of the Northeastern United States

Introduction | Literature Review| Data and Analysis | Conclusion| Sources | Storymap

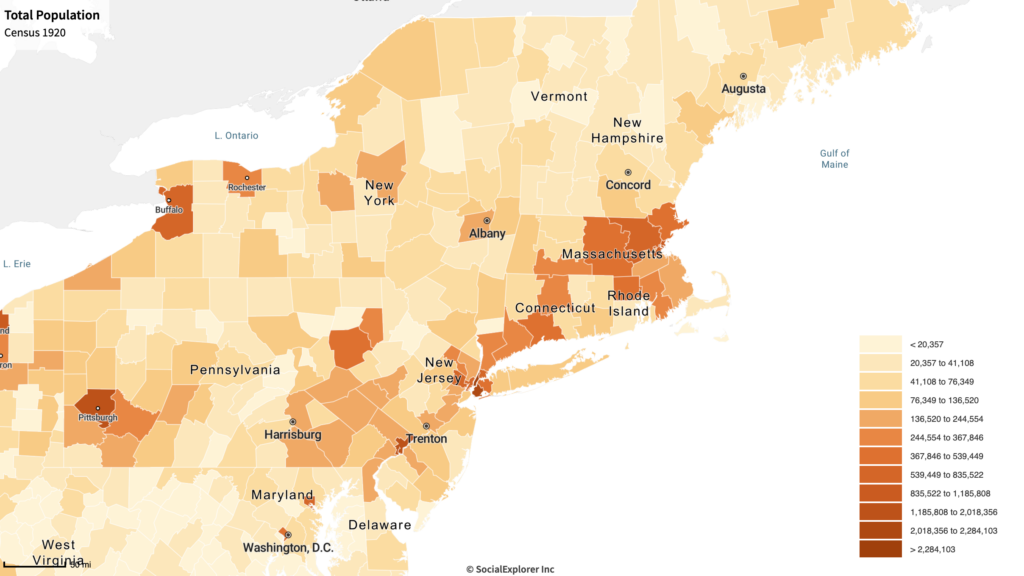

In the early 19th century, people continued to move from the country to the newly forming cities. It is clear from the map below that the Northeastern metropolitan areas boasted the largest populations, especially New York City. As the cities grew and technologies got better, people’s fears surrounding immigration and industrialization grew. White men were threatened by the new social order, in which immigrants, African Americans, and women were included (Jordan 2010, p. 616). This growth coincided with a push to go back to nature. Relating back to pioneering and westward expansion, nature became the ideal, and cities were blamed for crimes and immorality.

It clearly follows that most children and youth were concentrated in and around these cities, but children’s educators and advocates pushed for children to be sent away to the country side. Summer camps were offered away from cities and tucked away in nature. Upstate New York, Vermont, and Maine were perfect for summer camps, and boasted many programs each summer.

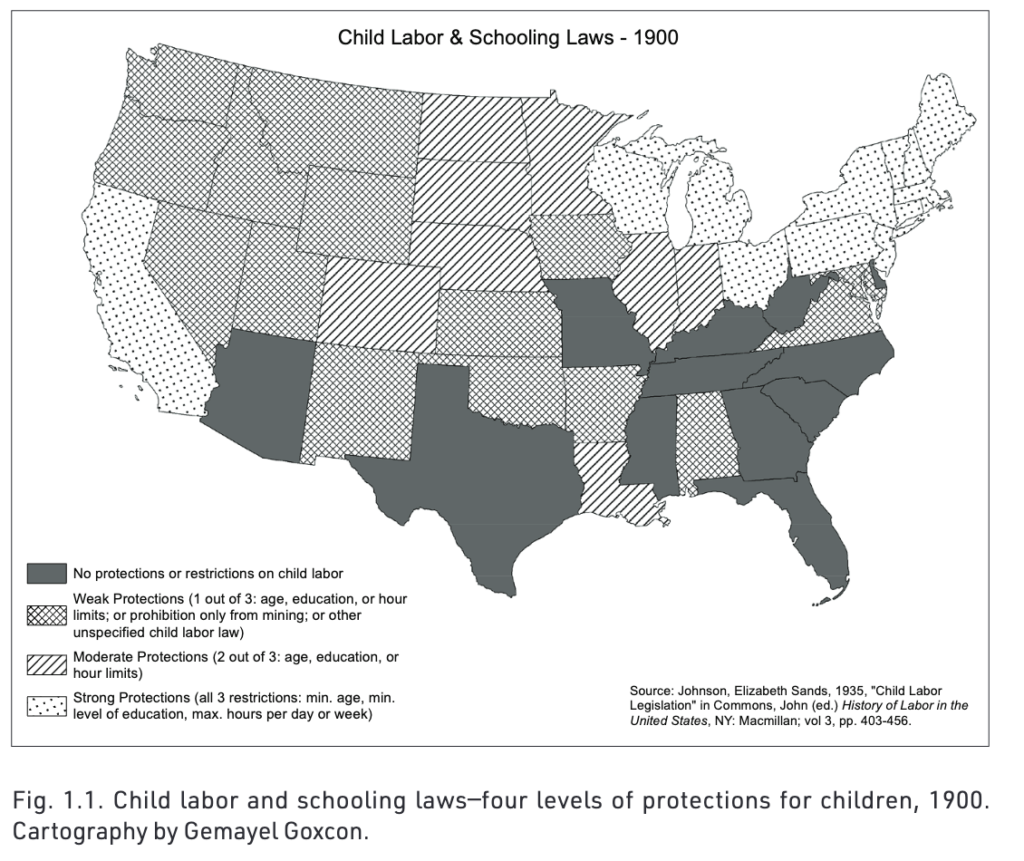

Camps emerged alongside child protections such as labor and schooling laws. As compulsory schooling laws, and anti-child labor laws kept children in school and out of work, there was a growing need for summer activities (Paris 2008). Subsequently, the most common social group attending early summer camps were middle and upperclass city children. Poor and working children did not have the time or expenses necessary to attend summer camp. Pictured below is a map of child labor and schooling laws at the 20th century. The Northeast and California had the strongest child protections, with both minimum age, minimum level of education and maximum hours per day or week worked. While other regions varied, the South was the worst. This is one of the reasons for the prevalence of camps in the Northeast; more children were going to school and not working in the summer. As child reformers began to place value on children’s purity protections were put in place to protect this new concept of “childhood” and raise children to be good citizens, summer camps being one of these protections.

Traditional summer camps were different from schooling, because instead of lessons they offered more kinetic activities such as athletics, camping, swimming and crafts. The table below shows common activities boys did at summer camps in the early 20th century. Summer camp activities give researchers a good understanding of what camps leaders felt was important for their development in the space, and also what children enjoyed.

| Common Camp Activities at Boys’ Camps in Vermont | ||||

| Year | 1924 | 1926 | 1928 | 1935 |

| Number of Camps | 23 | 23 | 33 | 27 |

| Activity | Number of Times Mentioned | |||

| Sports, Athletics | 12 | 10 | 14 | 11 |

| Watersports | 11 | 10 | 13 | 7 |

| Canoeing | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

| Outdoor Camping, Hiking Trips | 9 | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Riding | 7 | 6 | 9 | 10 |

| Nature Study | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Drama | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| Tutoring | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Arts and Crafts | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Woodworking | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

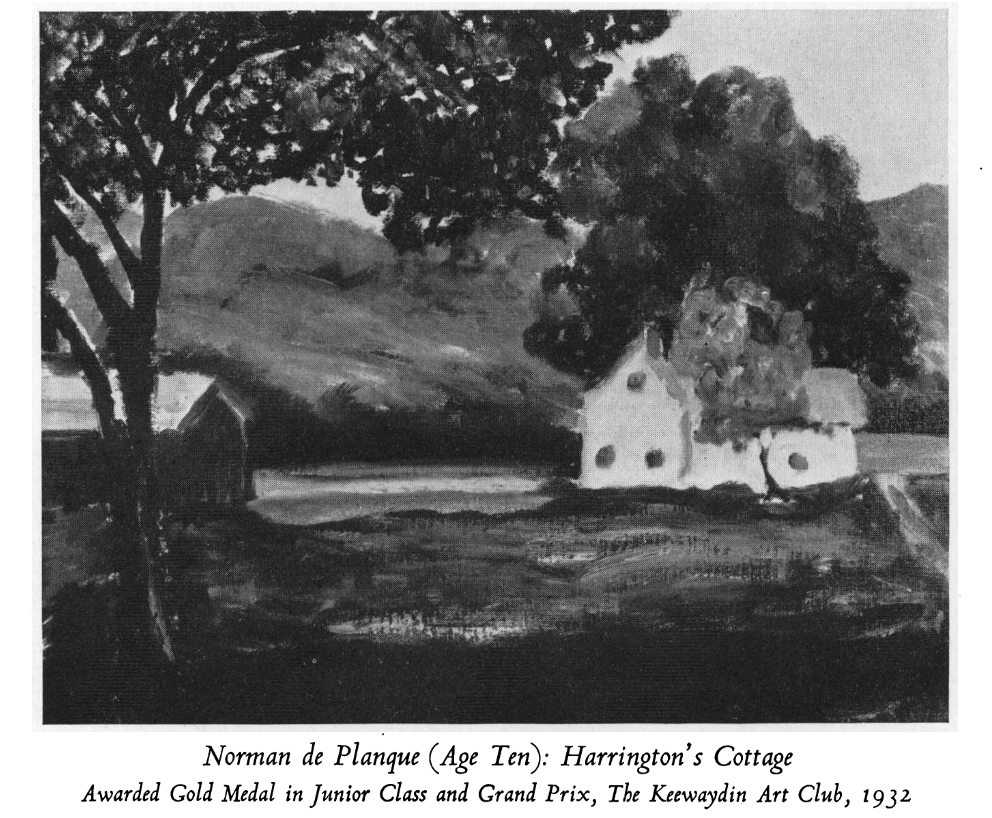

The most common and mentioned activities across all years were sports/athletics and watersports. This is not too surprising, but it does suggest that access to a body of water was extremely important for summer camps. In fact this is true according to Porter Sargent, who wrote most children are required to learn to swim at camp. Sports meant regular ball games such as tennis, but also included general athletics and play. Below is a table of the common sports mentioned. Great emphasis is placed on boys’ athletic capabilities. This is because camps were aimed at turning “lazy city boys” into strong and healthy natural boys. Outdoor hiking and camping was mentioned often, which alines with the summer camp mission of bringing boys into nature. Canoeing was common. I thought it was interesting how relatively popular riding was, and how this popularity grew overtime. Horse riding was more popular with girls camps, but boys camps also had riding programs (Sargent 1928, p. 72). Campers could learn how to care and connect with animals through horses, and could also ride them as transportation. Although boys were required to do athletics and nature focused activities, they were not barred from the arts. Drama and arts and crafts were mentioned each year. A education experiment on art programming conducted in Vermont, the Rocky Mountains, and Canadian summer camps from 1930 to 1931 found that male campers eagerly and enthusiastically threw themselves into painting (James 1932). Through art, the boys gained a sense of pride in their work, and an appreciation for the natural subjects they painted. Interestingly, the author G. Watson James states that this program “paves the way to convincing the youth of our country that art is a man’s work, calling for brain and brawn and a battle” (James 1932, p.370). Although art programming was common, camp educators still had to prove that the activities were not turning boys into “sissys” (James 1932, p. 368).

What these activities except tutoring have in common is that they are all hands on activities, where the child is experiencing the act through their body. Camp was not for passive learning, it was for active, kinetic exploration. One specific learning philosophy called nature study was common in the beginning of camp programming. Nature study was student lead, with nature as the teacher. Instead of classroom instruction, children naturally lead themselves in the exploration of concepts that interest them. Sargent states,

“A rest by the roadside or during a quiet bit of paddling, a flower or a passing bird or insect to start the questions, and a well-informed Counselor to answer, and before the campers realize it their eyes and ears are opening to a new and wonderful world which lies about them awaiting their newly aroused faculties” (Sargent 1926, p.48).

Sargent also noticed a decrease in the mentions of nature study by camps in 1926, which aligns with the table data. It was hard to arouse interest in campers for anything to do with “study” (Sargent 1926, p.48). As camps became more mainstream, they began to specialize in more activities and and in some cases lost the natural core of early summer camps. Some specialty camps to note: Religious camps (Catholic, Jewish), tutoring camps, camps to bring poor children into nature, camps for the disabled, and health camps.

| Specific Sports Mentioned | ||||

| Year | 1924 | 1926 | 1928 | 1935 |

| Number of Camps | 23 | 23 | 33 | 27 |

| Sport | ||||

| Tennis | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Baseball | 3 | 2 | ||

| Basketball | 1 | 1 | ||

| Track | 3 | 3 | ||

| Golf | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Swim | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Boxing | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Wrestling | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Riflery | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Archery | 2 | 1 | ||

| Fencing | 2 | 1 |

In addition to more broad terms like sports or athletics, some camps mentioned specific sports as shown above. Some camps may have offered these sports, but not specified in their descriptions, so the methods for this table aren’t the best, but maybe there’s some meaning to the fact that these camps felt it was important to specify. At the least it shows some sports offered at camps. Along with more common sports, some camps offered more specialty activities such as archery, riflery, and fencing. I was surprised at golf, which seems more uptight. Sports like archery that were historically used for hunting, while mostly obsolete now, served to cultivate children’s more primal selves.

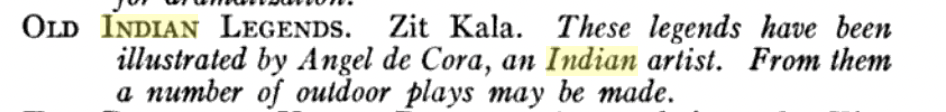

Camp programming often included cosplays of Native American traditions so that white children could experiment with “darkness” (Paris 2008, p. 193).

Page 89

In the image above, Porter Sargent encourages camp leaders to use old Indian legends as material for plays. Camp programmers advertised “exercises and recreations of the American Indian” (Porter 1924, p.398). When including “Indian Lore” in their programming, camps were viewed as more authentic to the natural traditions of early American life.