In this section, I use a mix of quantitative and primary source documents in order to highlight the themes previously stated in the literature review.

Population Density compared to Wage & Salaried Workers

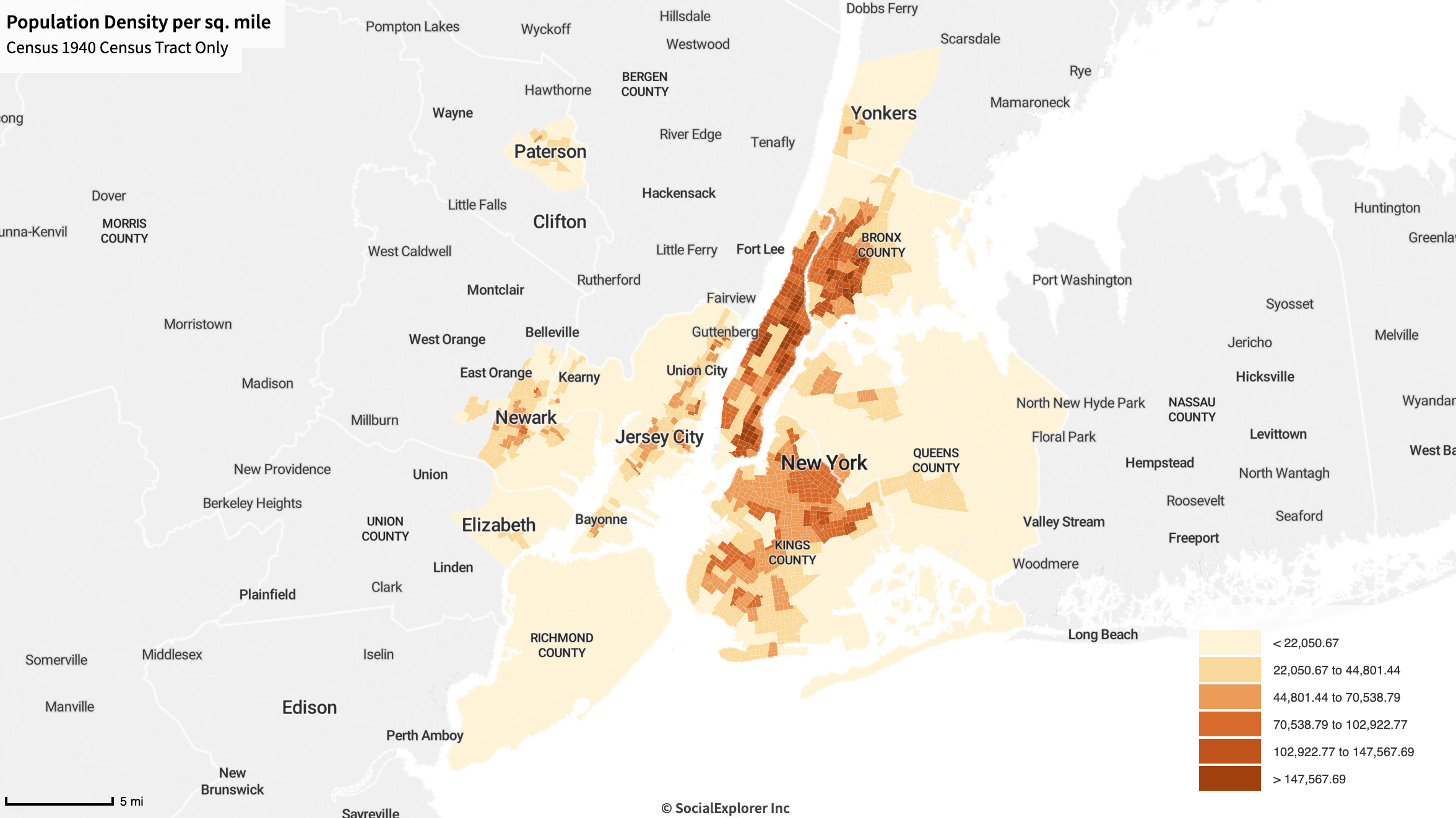

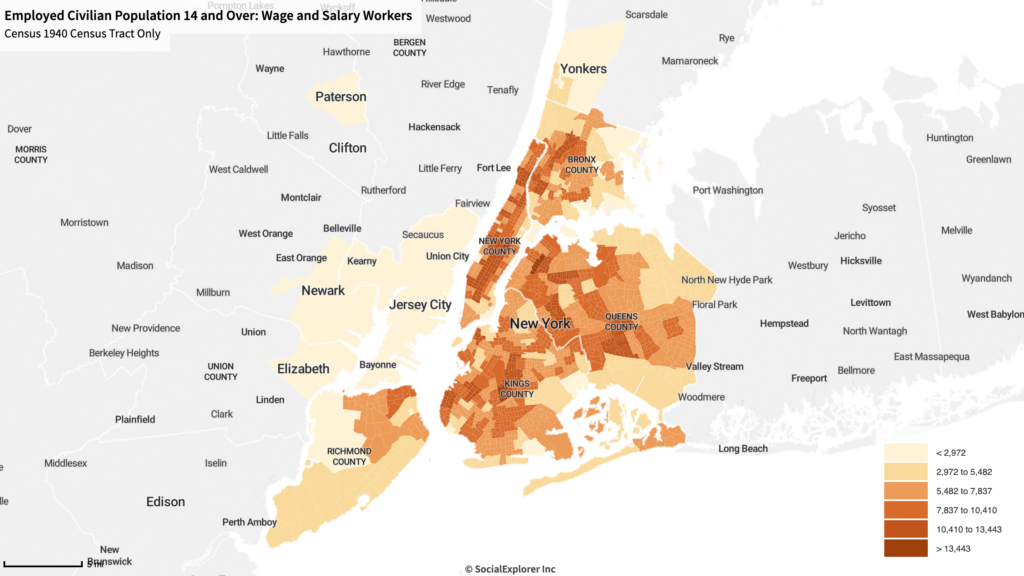

Below are two maps of New York City that showcase data taken from the 1940 census. I have chosen to showcase population density along with the number of wage and salary workers over the age of 14 in order to draw conclusions about the availability of space for children of the time.

Population Density:

Employed Wage & Salary Workers:

The first map shows the incredible population density within New York City’s neighborhoods, 147,000+ people per square mile in some tracts. The second map details the amount of employed salary and wage workers in each tract, which mostly reflects the number of people within each tract.

I had originally wanted to use income metrics in combination with population density to support the idea that poorer communities were the ones with the least amount of available space to support children. However, I could not find that data through Social Explorer for 1940. I chose to use data that excluded employers and business owners with the idea that they would be making more money on average than a typical waged worker in 1940. Although the data is not perfect it suggests that children were living in very condensed neighborhoods and there was not much domestic space available for them to exist in. Therefore, it can be inferred that streets offered much-needed public space for children to play in.

Photo: Riis, J. A., photographer. (ca. 1890) Boys Playing in Street. , ca. 1890. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002710286/.

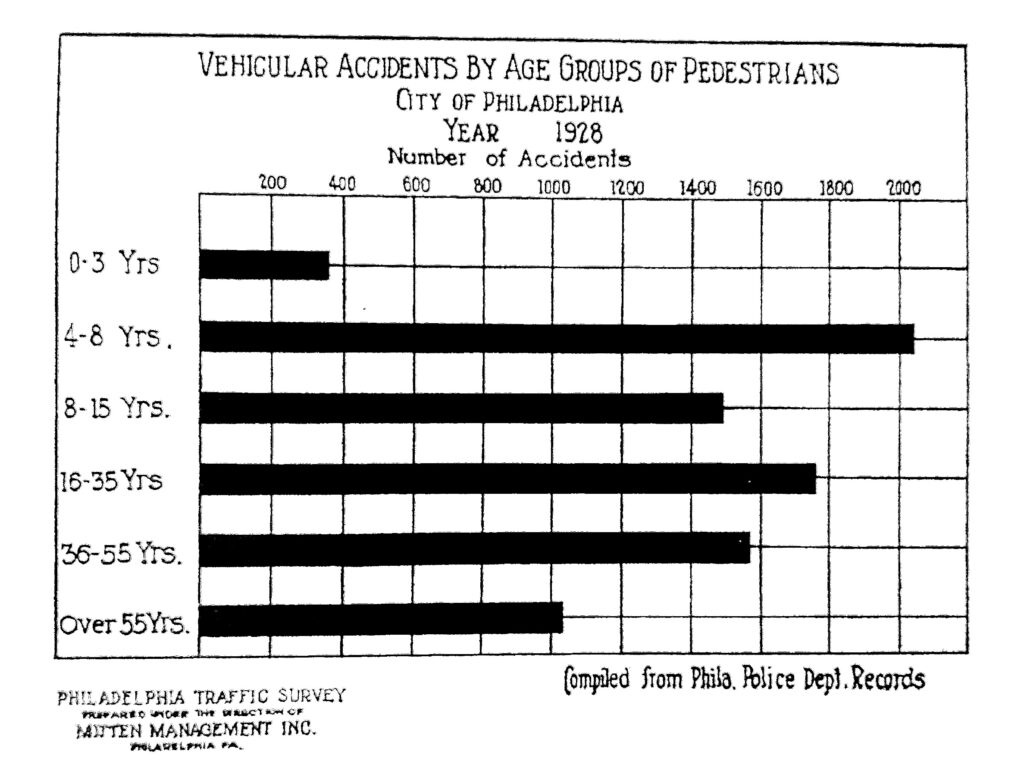

Vehicular Accidents by Age Group

This graph from the Philidelphia Traffic Survey shows the number of accidents between automobiles and pedestrians broken up by age group. Although this graph only shows accidents reported and not the severity of each accident (i.e. death/injury), it is clear from the data that young children between the ages of 4 and 8 were the most endangered by cars on city streets. They accounted for over 2,000 accidents in 1928. With this data, we can speculate that cars proved to be the most life-changing for younger individuals because they had the most severe effects from the changing landscape of streets. By life-changing, I mean that cars had the most direct impact on how young children were able to live and experience the world around them because cars created more danger for them than any other age group.

Traffic Tensions

The issue of traffic was not just limited to the East Coast urban areas. In fact, the entire United States was dealing with this new increase in drivers throughout many of its urban environments. For example, this bulletin article from St. Louis raises concern over how traffic control is being approached.

St. Louis had approximately 16,000 motor vehicles registered in 1916. The 1923 registration exceeded 100,000 motor vehicles and this figure will beincreased to 200,000 by 1928. Traffic counts show an annual increase of 25 percent in vehicle movements upon the city’s streets. Something more than traffic regulation is needed. Freedom of traffic circulation is a commercial necessity.

(Bartholomew, P. 1)

In terms of children, this resulted in increased tensions surrounding child safety. A whole host of campaigns started with the goal of promoting safer streets.

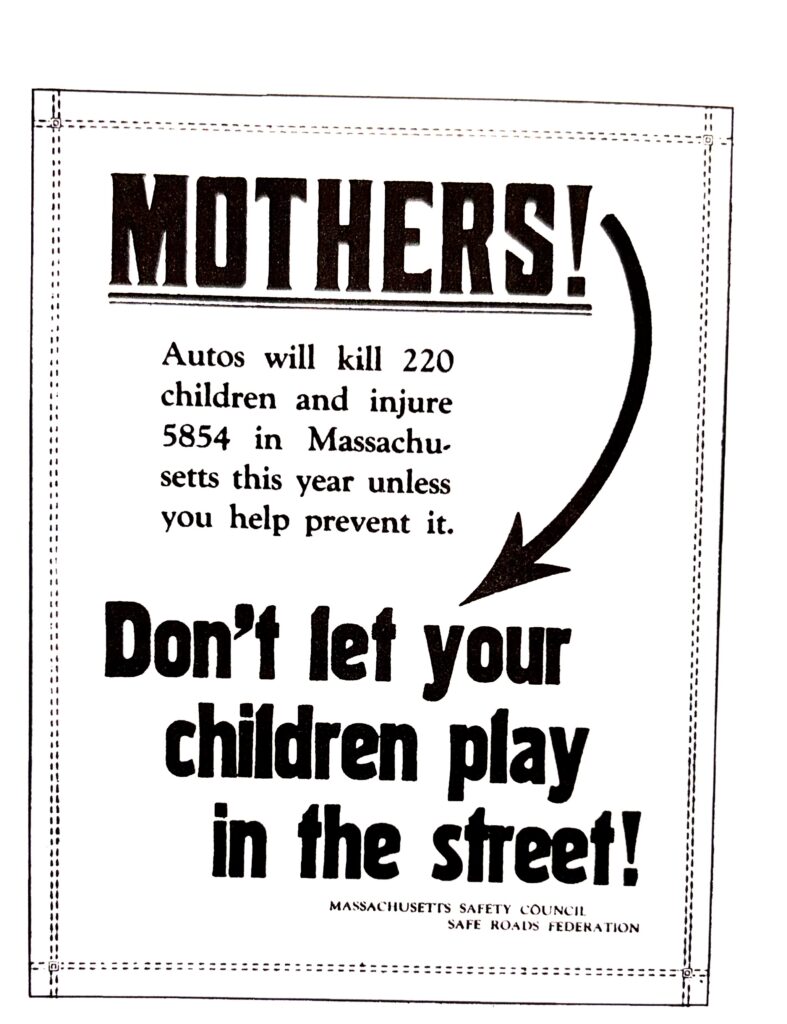

This poster from the Massachusets Safety Council was one of many produced in 1923 and distributed all around the state specifically in urban areas such as the Boston Metropolitan Area.

This type of public notice shows the shift away from viewing motorists as the outside group within America. At this point, by the early 1920s, lobbyists and policy had cemented the car as a staple of the American lifestyle both in and out of cities. The emphasis shifted towards holding children accountable and by extension their caretakers, often mothers. It was expected that children become domesticized for their own safety, gone was the availability of public space for play.

Brooklyn Anecdote

My grandmother grew up in Brooklyn during the early 1930s. While creating this project I talked to her about her experience living in Brooklyn during the period I was researching. Her main points of memory supported my research and supported the idea of streets as public play spaces.

My favorite memories growing up were always outside, we loved to play ball in the street and the whole neighborhood would gather up every day after school let out to form teams and play games until our parents got back from work.

Anne Guba

I thought that this was an important aspect to include in my project because it ties in with the psychological impact of space on children. My grandmother’s core childhood memories were defined by the space that they took place in, the streets of Brooklyn. The drastic change that cars had on public space seems to suggest a shift in public space usage by children, which in turn reshapes the societal construction of what it means to be a child.

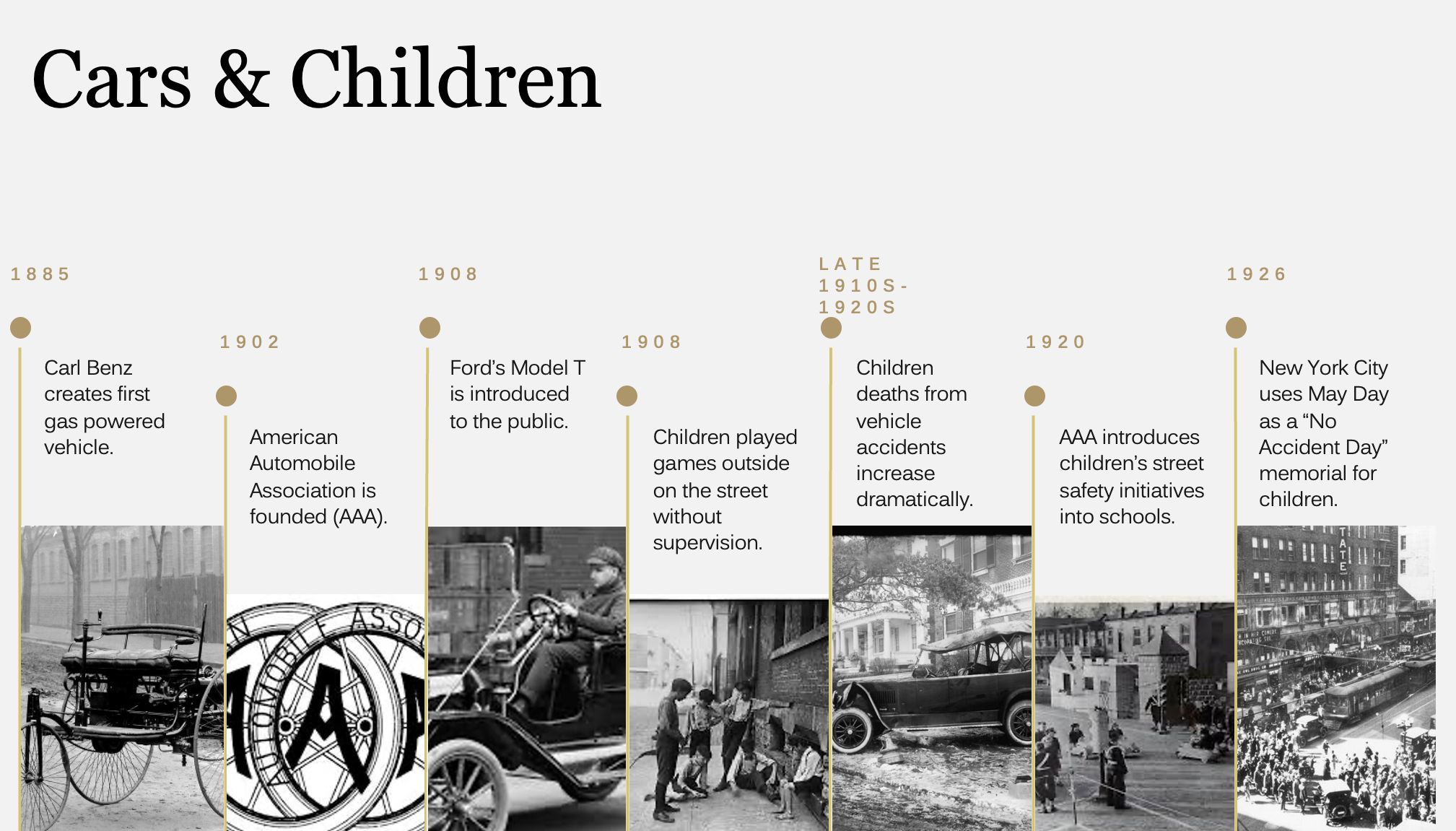

Cars & Children Timeline