Demographic Data

Understanding the historical and geographic contexts of primary sources is key to analyzing them fully. The United States had complicated, changing social demographics in the early 1900s. By examining the subject of doll play within the context of the larger forces at play in the country, we can understand what factors influenced it as well as how it may have varied geographically.

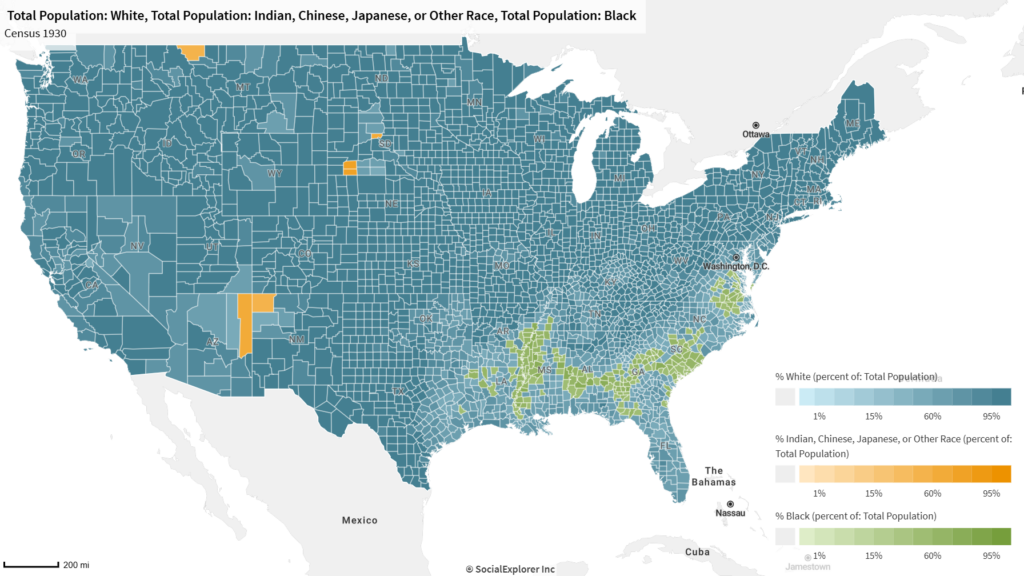

In the early 20th century, the United States was still highly segregated by race. Most southern states had a high black population, while most northern states were at least 90% white. This meant that many children didn’t regularly interact with people of different races and instead relied on toys and media to learn about the world. It also meant that for the black children who lived in mostly white areas, positive representation was critical for self-esteem.

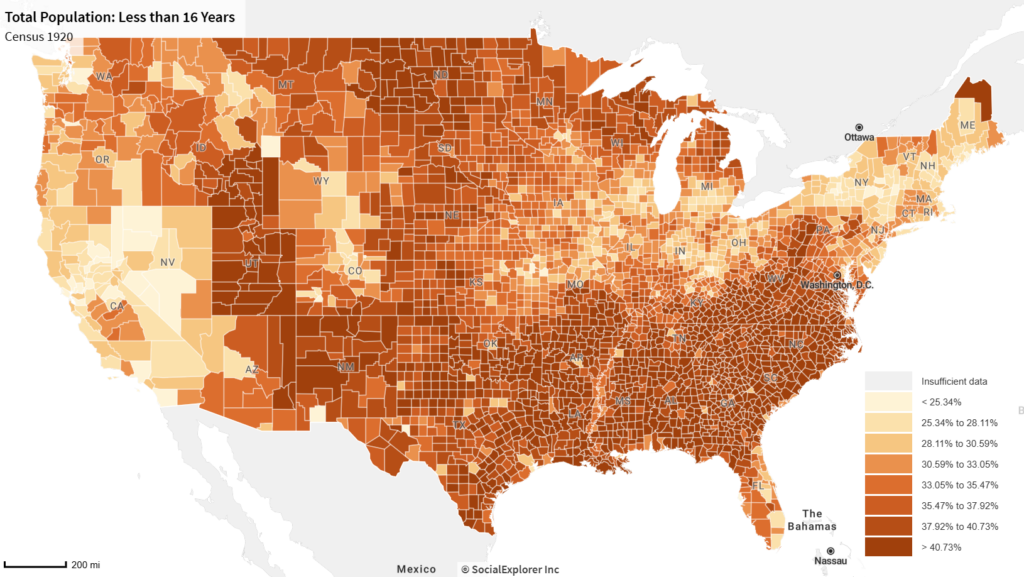

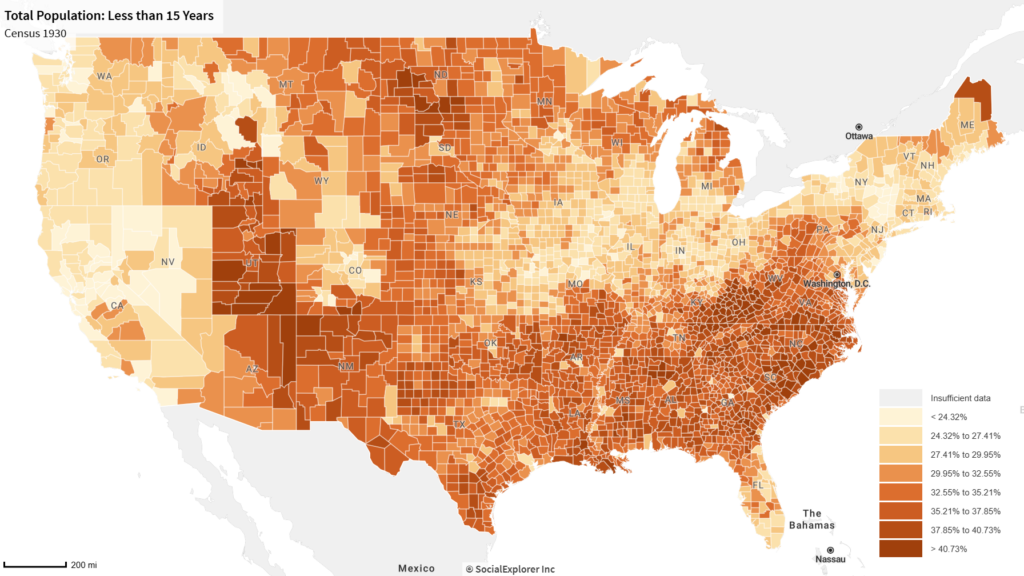

The percentage of young people in the United States decreased from 1920 to 1930, with particularly sharp declines in the Northwest and Midwest. Areas that had less children likely didn’t have as strong of a childhood culture, and the children likely relied more on toys and games to entertain them than friends. However, this decline also mean that families had more money to spend on each child. The children had more of their own toys to play with, and their families could afford nicer, more expensive toys.

Change over time

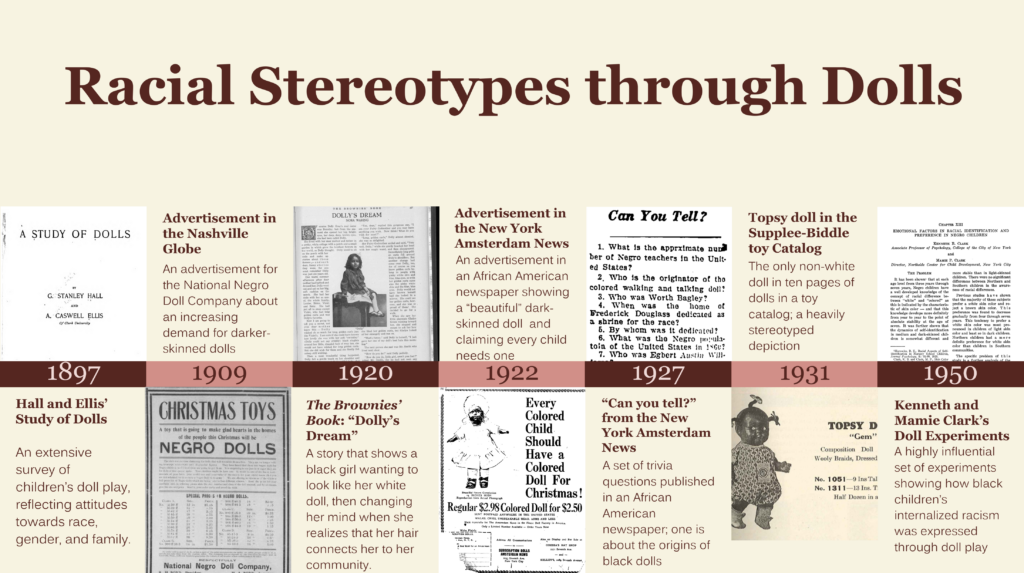

Representation marketed towards black children improved drastically during the early 20th century, but non-white dolls marketed towards the general public remained extremely stereotyped and represented only a small fraction of the dolls available.

Hall and Ellis’ Doll Study

In 1897, G. Stanley Hall and A. Caswell Ellis published a thorough study on children’s play with dolls. It was the first scientific study to focus specifically on dolls. The authors used survey results from 648 children, mostly from the Northeast United States. The children’s age and gender were included with results. While data on race was not collected, there are many references to racial stereotypes and racialized dolls in the children’s answers. The survey questions attempted to analyze every aspect of doll play, from physical construction to pretend funerals. Their study provides insight into the daily lives and attitudes of children at the turn of the century and serves as a foundation when studying how children’s lives changed over time.

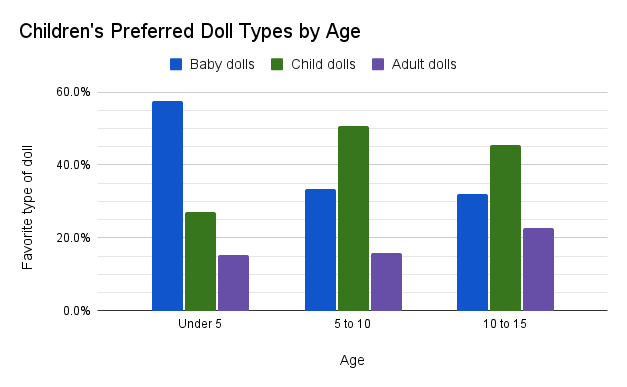

dolls, and adult dolls, using data from Hall and Ellis (1897)

Hall and Ellis found that children often viewed dolls as direct reflections of real life and used them to both learn and practice social values and norms. The study contains detailed descriptions of the way children disciplined their dolls. The types of punishments given as well as the children’s attitudes towards punishing their dolls are a clear reflection of the societal norms at the time. The children impart virtues and character traits onto their dolls, describing them as “good”, “truthful”, and “obedient”. They punish the dolls for many of the same things the children were likely punished for themselves such as jealousy, talking back, and not sitting still. Hall and Ellis also asked children of different ages about the type of doll that they liked best (summarized in graph above). They found that children generally preferred to play with dolls that were modeled after children close to their age or slightly younger. Children liked having dolls that represented themselves and the people around them.

“A colored doll may be specially liked because others hate it, but fair hair and blue eyes are the favorites”

Hall and Ellis (1897)

Hall and Ellis first touch on the idea of race in doll play during their descriptions of doll construction and clothing. They mention how children said that dolls with dark skin sometimes don’t need clothing “Because they are so black nobody can see.” The authors go on to state that the only reason children sometimes enjoy black dolls is because others dislike them. They also describe how ideas of self-consciousness and shame play into doll preferences. The racial aspects of doll play are explored further in the section on doll hygiene. One child is quoted saying, “I could not get my doll clean because he was black.” Another particularly striking example of children’s attitudes towards black dolls is found in the section on doll funerals. The authors describe a girl who was so afraid of her black doll that she burned it in the fireplace and was afraid of its ghost for a long time after. While we don’t know these children’s race or background, it’s clear that they were acquiring a bias from somewhere. Through doll play, children expressed views that black people were scary, unclean, and overall less valuable than white people. Given the lack of racial diversity in many northeastern states, it’s likely that most of these children’s ideas about black people were obtained through the inaccurate, stereotyped dolls that were common at the time.

Racialized Dolls in the Mass Market

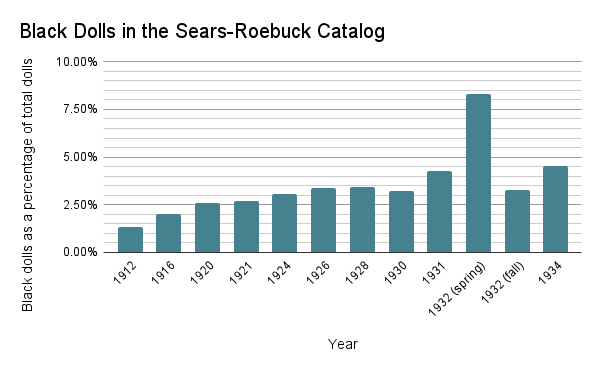

Positive images of black children increased sharply in the early 20th century, but they were still noticeably absent from media and toys marketed towards white children. When black dolls were advertised to the general public, they were almost always based off of racist caricatures. The Sears-Roebuck catalog didn’t contain black dolls until 1912, and the dolls they advertised were heavily stereotyped. Their production of black dolls increased slightly through the years, but rarely passed 5% of the total dolls.

begins in 1912 because until then, Sears-Roebuck only advertised white dolls.

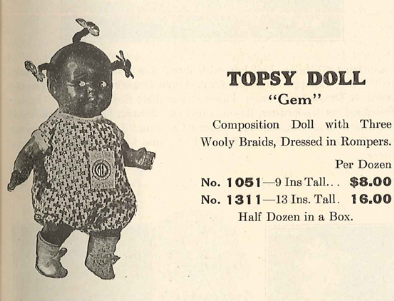

This pattern is glaringly obvious in toy catalogs from other brands. After pages of nicely dressed, beautiful, feminine dolls with white skin, most catalogs include no more than a few dolls with dark skin. The dolls are often based on racist caricatures, with hair that is described as “wooly” and clothing that is distinctly less feminine than that of the white dolls.

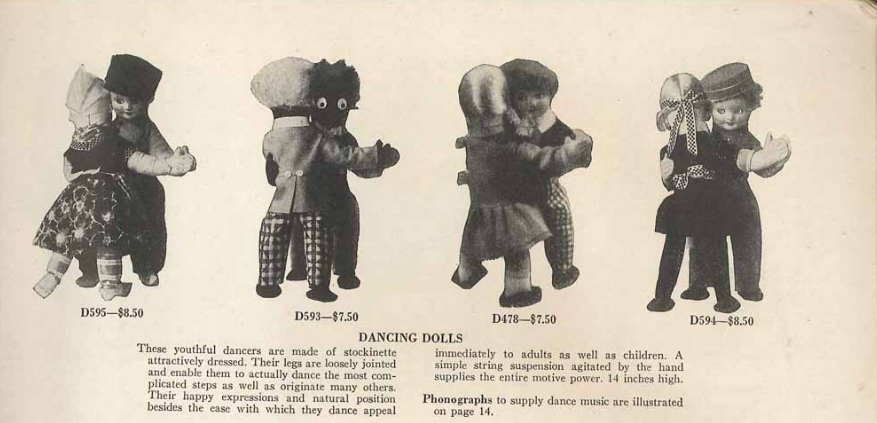

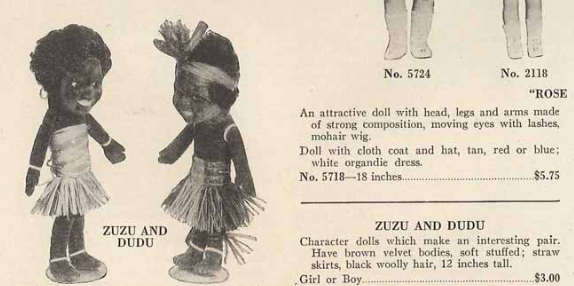

A 1929 catalog from F.A.O. Schwartz contains two sets of non-white dolls in its three pages of doll advertisements. Both are exaggerated, racist caricatures. On one page, four pairs of “dancing dolls” (above) are advertised, with three white pairs and one black pair. The white dolls have painted faces and one in each pair wears a skirt. The black dolls have big, round eyes and no other discernable facial features. Neither of them wears a skirt. The dolls push a message that black people are less beautiful and, importantly, less feminine than white people. The other non-white dolls advertised are a pair of “character dolls” named ZuZu and DuDu (bottom left). The dolls are dressed in straw clothing and have short, curly hair. Their heads are comically big, especially when compared to the rest of the dolls on the page. The 1934 Supplee-Biddle Hardware Company shows the same pattern. The catalog contains ten pages of doll advertisements, and only one black doll. The advertisement is small and depicts a “Topsy” doll, which was a popular racist caricature at the time (bottom right). While the catalog contains dolls of all ages, the Topsy doll is modeled after a baby. The two toy catalogs advertise black dolls as anything but beautiful and feminine, while the white dolls next to them seem to be designed to be as beautiful and desirable as possible.

Beauty Standards for Black Children

Over time, demand for non-stereotyped black dolls grew. Mainstream toy companies still manufactured either stereotyped black dolls or none at all, but African American newspapers began to advertise new, more accurate dolls for black children. A 1909 advertisement from the Nashville Globe cites the new black dolls as an important source of racial pride and dignity. It describes the stereotyped dolls as “scarecrows and disgraceful figures.” In 1922, an advertisement appeared in the New York Amsterdam News for a new line of black dolls. Similarly, this advertisement claimed that every black child needed a doll that looked like them. However, it placed an even greater emphasis on the doll’s “beautiful brown complexion.” The advertisement took up a quarter of the second page of the newspaper and contained a photo of the doll. The fact that a doll advertisement was displayed so prominently in one of the most important African American newspapers highlights the importance that black dolls had in black culture and activism. Advertisements like these represented an important shift in the way beauty standards were presented to black children.

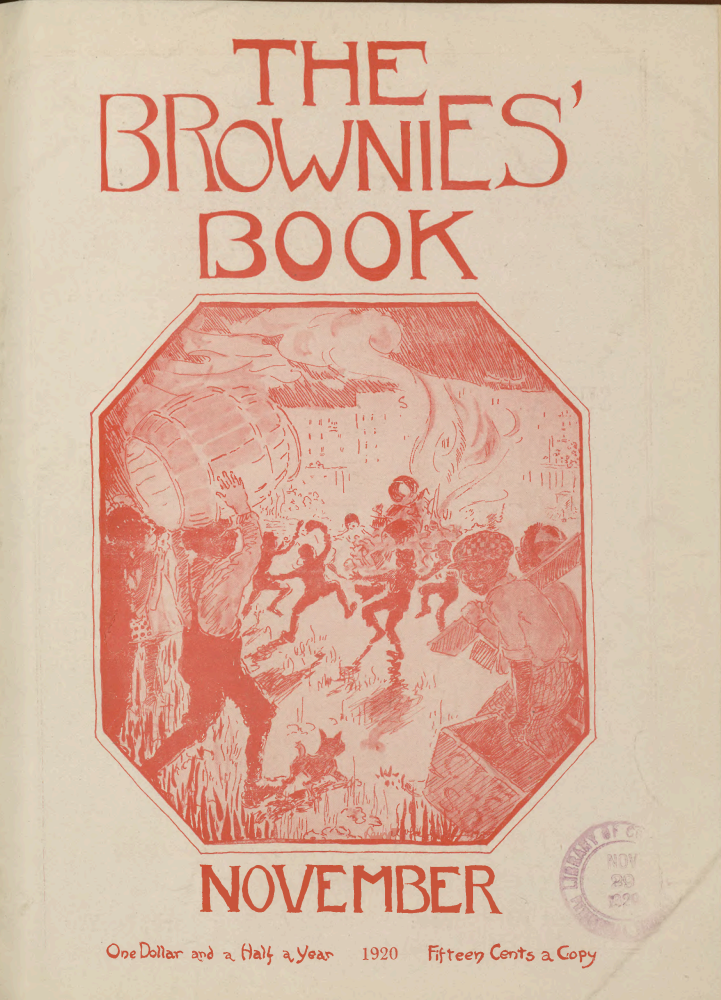

The Brownies’ Book, a magazine published by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1920 and 1921, served as an important source of entertainment and representation for black children. In November 1920, a story titled “Dolly’s Dream” was published. In it, a black girl named Dolly wishes that she could have curly blond hair just like her favorite doll. She dreams that she is visited by a fairy godmother who casts a spell to give her blond hair and white skin. Dolly is initially happy, but soon realizes that all of her friends and family are avoiding her because they don’t recognize her. When she wakes up, she is relieved to find that her hair is no longer blond and expresses love for her “cwinkly black curls”. The author of this story was trying to push back against the beauty standards that were common in dolls at the time. The story reminds children that they are beautiful and should love themselves, even if the popular images of beauty are different.

“I am so glad it was all a dream and I just love my ‘cwinkly’ black curls”

“Dolly’s Dream” by Nora Waring