The original portrayal of Sita in the Ramayana is from a very different era of time, yet the role of Sita has been able to move across these differences to still connect with people. Sita’s applicability to women is not limited to India, but rather Sita connects with women all over the globe, especially those who have a connection to Hindu traditions.

Sita’s outward reactions to the many indignities imposed on her are seen as dignified and appropriate. She does not go against Rama in anger, nor does she try and turn others against Rama. When Rama is banished to the forest for fourteen years Sita is not upset at losing the comforts of the city and palace, but only speaks up to ensure she stays with her husband. This is viewed as proper devotion to her husband, and a fulfillment of her duties as a devoted wife. When she is brought to the forest by Rama’s brother at the behest of Rama she does not return to the city to try and make a public reversal of his decision, rather she stays and lives in the forest where she was left. She does not bring shame to Rama by contesting his decrees, and as such this is viewed as her again honoring her husband. This is used to remind women the ideal is to not bring shame on their husbands for any reason.

Sally Sutherland addresses this in her piece comparing Sita with Draupadi titled “Sita and Draupadi: Aggressive Behavior and Female Role-Models in the Sanskrit Epics.” Sita models turning the anger felt towards her husband inward, which Sutherland argues is seen as the culturally correct way. Sita models the preferred method for dealing with anger according to society. The many ways Sita was wronged by Rama is both typically and popularly believed to not be her fault, and even while she does not deserve the treatment she receives, she does not turn on Rama. For Sutherland, Sita’s unwillingness to return a wrong with a wrong shows her admirable strength of character. This understanding of Sita becomes something to be emulated by women over the course of history who have knowledge of the Ramayana story.

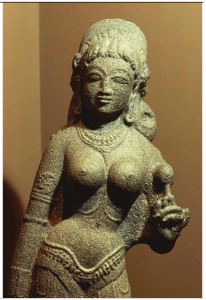

Even the artwork and imagery portraying Sita is used to show her as a strong woman. In this statue of Sita she can be seen as a strong, beautiful individual. This image helps to highlight the importance of Sita throughout history for women. According to other sources, such as Sutherland, Sita has been held up as the ideal all along because the cultural ideal of handling anger has not shifted. Sita is viewed as the ideal wife and woman, and considered to be beautiful and important in those roles. This image shows how she was thought of and imagined long after the original telling of the Ramayana, and yet still well before now. Sita is still considered to be a paradigm of the beautiful and ideal wife, her image as such hasn’t shifted, even as society has.

For women who are descendants of Indian culture located on the outside of that culture, Sita takes on more meaning. Not only is Sita dignified while directing her anger inward, she has experienced the impact of living outside her culture, first in the forest, then in her exile. Sita is not only able to survive this, she maintains her dignity giving multiple generations of emigrants a model. Anju Bhargava is one such person, and she addressed this in her talk “Contemporary Influence of Sita.” Bhargava relates the experiences of Sita to the experiences of immigrants with this quote,

“The immigrant parents are perceived to be a product of a society which calls for harmony of the entire community, not necessarily at the individual level. Ram sent Sita away sacrificing their personal happiness to do his duty as a king. So, many parents try to teach their children to adjust and adapt and accept what life brings because it is dharma.”

The message is that Sita can guide one in the process of adaption to and acceptance of whatever life may bring. Sita is a source of hope for these women.

While Sita is held up as an example of how to roll with life’s punches, she is also held up as the ideal wife. She exhibits signs of being both a good wife and an ideal woman by her willingness to sacrifice herself on the funeral pyre for Rama, her trial by fire. For Hess the relationship between Sita and Rama demonstrates Sita being the worshiper and devotee to her husband’s lord of the relationship. Hess argues that this relationship between Sita and Rama is used to encourage this model to be followed, the wife is meant to become the devotee and worshiper to her husband.

Not all agree this is the lesson to be learned from Sita. Like Sutherland, Kishwar believes that Sita is important today for the way she reacts to actions and events around and against her. She remains dignified throughout the Ramayana, doing what it takes to stay with her husband, but other than that going along with his decrees. Her final rejection of him is seen as the final act of dignity. Sita is held up as an example that different situations require different reactions for the individual to maintain their own dignity. Sita’s actions in the Ramayana show women that it is important to stay dignified, to forgive and make concessions for one’s husband, but that it is also important to stick up for yourself.

Others view and classify Sita’s actions as something else. They identify her actions that are the reason for the differing view. “Sita’s reaction involves both lament and protest… then she criticizes Rama… finally she has a pyre built and crawls on it to die” (Grottanelli, 7-8). Cristiano Grottanelli is making the argument about the process Sita goes through reacting from the failing of the solution to her original crisis, the exile of Rama and Sita into the forest and Ravana stealing her away. Sita laments, protests, openly rebukes and criticizes Rama’s devotion to his people over her, and then finally plans to die on a funeral pyre. In “The King’s Grace and the Helpless Woman: A Comparative Study of the Stories of Ruth, Charila, Sita” there is not a discussion on Sita’s dignity or her method of dealing with her problems through her life. Rather, he is looking at her actions. If others hold up the actions and reactions of Sita as admirable and to be mimicked, Grottanelli sees these actions from a different perspective. While Grottanelli is not looking at the intentionality of Sita’s actions his piece is still important to the understanding of Sita’s applicability to women now. For those who make the argument that Sita is viewed and should be viewed as the ideal wife and woman for her reactions there is often the theme that Sita can be viewed this way because of her way of reacting to the various transgressions against her. Yet Grottanelli shows that there are actions that bring this into question.

Sita is not the main character in the Ramayana, in fact she is given far less time than many of the other popular characters in William Buck’s translation. Yet the lasting importance of Sita to women is undeniable. She has been influencing and informing the ideals concerning the roles of women and wives since her conception in the Ramayana.