Ethnic and religious violence in India, between Hindus and Muslims, has increased in since the 1992 destruction of the Babri Masjid. Also, during this time the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and other right-wing groups emerged into the Indian political sphere. However, what has lead to this increase in animosity and violence? Is it a continuation of historical mistrust, rivalry, and hate? Or is it a new phenomenon that is created independent of historical relationships? Using various sources and scholarship on the BJP, other right- wing groups, and hindutva ideology, I will argue that political tools, such as media, history, and modern interpretations of the Ramayana, are used to socially construct a Hindu identity in relation to the Muslim ‘Other’. This has lead to an increase in anti-Muslim violence perpetrated by the BJP, other right-wing groups, and hindutva activists.

I would like to first draw attention to Matthew Cook’s “Reconstructing “Ram Rajya”: Tradition, Politics, and the Bharatiya Janata Party”. Cook’s article examines the BJP’s promotion of Ram Rajya, the idea of the “Golden Age” of Rama’s Kingdom, or an age of prosperity and Hindu unity. A large number of people, specifically media, believe that Ram Rajya will signify a return to the past and to the social systems that no longer have a place in much of modern India. However, Cook argues that media constructions of Ram Rajya as ‘regressive’, “fails to recognize that the BJP’s talk of Ram Rajya has little to do with returning to the past, but everything to do with gaining political power in the present” (Cook, 42). The BJP is using Ram Rajya and the Ramayana as a unifying agent for Hindus, and through Ram Rajya politics, the BJP aims to gain political power and Hindu hegemony over the Muslim ‘Other’. This requires a strong unified body of Hindus, whose identities are constructed in relation to this Muslim ‘Other’.

I would now like to turn to an article written by Susanne and Lloyd Hoeber. Their article examines Hindu-Muslim hate and animosity as a modern construction. For them, the Ramayana mega-series, as well as other events, plays, and accessible media act as a catalyst for the BJP’s rise to power and for promoting the Muslim ‘Other’ message. They argue that the Ramayana mega-series, among other things, operate in a new space [mass media, television, etc…] to promote Hindu unity and create a Muslim ‘Other’. “In this space a new public culture is being created and consumed. Distant persons, strangers, create representations of public culture for anonymous viewers. Values and symbols, meaning systems and metaphors, can be standardized for national consumption” (Hoeber, Susanne and Lloyd, 26). Through this socializing lens, identities, and values are internalized by the masses. Thus, inherent in the Ramayana is the ability to influence peoples’ actions and alter their perception of other people. In the context of violence, the 1992 destruction of the Babri Majid, plays a large roll in identity construction.

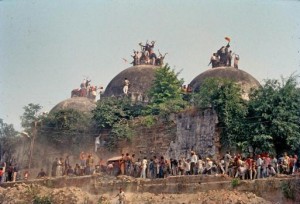

The Destruction of the Babri Masjid. Photo by: Sanjay Sharma

The destruction of Ayodhya’s Babri Masjid by a mob of roughly 300,000 Hindus was an extremely controversial event in recent Indian politics. The mob was organized by the BJP as well as other right-wing political groups, and its destruction resulted in riots that killed roughly 1500 people (Shuja, 39). The Babri Masjid, built by the Mughal Emperor Babur 430 years ago, stood on a site believed to be the birthplace of Rama. Thus, it is a location of extreme significance to Hindu nationalists and hindutva culture, and its destruction is a symbolic rejection of Mughal erudition and “the modern, liberal, educated, well-informed Muslim who has an open mind and cosmopolitan outlook,” the Muslim ‘Other’ (Shuja, 41).

In “The Violence of Security: Hindu Nationalism and the Politics of Representing the Muslim as a Danger,” Dibyesh Anand argues: “Hindutva is targeted at transforming the Indian state and controlling the Muslim and Christian minorities. At the same time, the primary goal is to transform the Hindus, to ‘Awaken the Hindu nation’ (See Chitkara, 2003; Hingle, 1999; Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, 2003)” (Anand, 204). I would argue that this image is, in a sense, a manifestation of this aspect of hindutva ideology that Anand discusses. The fact that the event was somewhat swept under the rug in terms of a political response demonstrates the power that a unified group of Hindus hold over the Muslim minority. Furthermore, this event only helped to increase Hindu nationalism, which subsequently strengthened hindutva sentiment in general and support for the BJP in particular.

Anand continues to explore the identity politics of the BJP and how the Muslim ‘Other’ is constructed in order to promote Hindu Security: “Security is closely linked with identity politics. How we define ourselves depends on how we represent others. This representation is thus integrally linked with how we ‘secure ourselves against the Other… The Other gets reduced to being a danger and hence an object that is fit for surveillance, control, policing and possibly extermination” (Anand, 206). Creating the Muslim ‘Other’, in this light, allows for acts of violence to be legitimized and perpetrated by the Hindus who have been subject to the socializing agents that construct their “righteous” identity in opposition to the “dangerous” Muslim ‘Other.’ However, there is more at play beyond identity construction. State institutions also play a big role in facilitating and allowing for violence to take place.

Ward Berenschot details the role of state-institutions in violence and rioting. He points out how politicians, police, and other figures associated with the state promote anti-Muslim ideologies and violence: “The political networks that facilitate the interaction between state institutions and citizens are to a large extent the same networks engaged in the instigation and organization of communal violence” (Berenschot, 415). This argument points to various ways in which the idea of the Muslim ‘Other’ is promoted by the state: It highlights one of the political tools that can be used to construct the identity of the Muslim ‘Other’, and it allows for acts of violence to be perpetrated by Hindus.

The image of the Babri Masjid’s destruction works well with both Berenschot and Anand’s critiques. State institutions allowed for the destruction of the mosque, and they were also very slow in responding to the violence that followed. Furthermore, it also represents the rejection and marginalization of the Muslim ‘Other’ in relation to the Hindu. These factors have not only allowed for violence to take place but also have legitimized that violence.

Bibliography

Anand, Dibyesh. “The Violence of Security: Hindu Nationalism and the Politics of Representing ‘the Muslim’ as a Danger,” The Round Table Vol. 94, No. 379, 203-215 (April 2005)

Berenschot, Ward. “Rioting as Maintaining Relations: Hindu-Muslim Violence and Political Mediation in Gujurat, India,” Civil Wars Vol. 11, No. 4, 414-433 (December 2009)

Buck, William. The Ramayana (University of California Press, 2012)

Cook, Matthew. “Reconstructing “Ram Rajya”: Tradition, Politics, and the Bharatiya Janata Party,” Hinduism and Secularism: After Ayodhya, ed. Arvind Sharma

Hoeber, Susanne and Lloyd. “Modern Hate,” The New Republic, March 22, 1993.

Pollock, Sheldon. “Ramayana and Political Imagination in India” The Journal of AsianStudies, May, 1993, Vol.52, p.261(37).

Shereen Ratnagar. “Archaeology at the Heart of a Political Confrontation,” CA Forum On Anthropology in Public, Vol. 45, No. 2, 239-259 (April 2004)

Sharif Shuja. “Indian Secularism: Image and Reality,” Contemporary Review 287.1674 (July 2005): 39

Image: www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/history-and-culture/in-the-name-of-the-people/article91762.ece