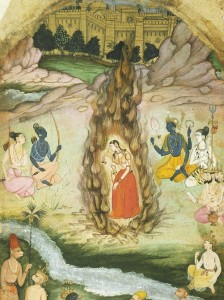

7. Sita’s Ordeal by Fire, From a Ramayana. Ink and color on paper. 1600. The American Council for Southern Asian Art Collection at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. ArtStor http://www.umich.edu/~hartspc/acsaa/index.html. October 12, 2014.

Sita (popular heroine of the Ramayana), as I understand her, is no more than a woman who is desperately in love with her husband. Personally, I think we have all seen the consequences and joys that come to those who will do and/or sacrifice anything for love. Two of the most powerful forces in our world are love and faith and Sita happens to be wrapped up in both. With power comes manipulation, however, as is seen across the world in most political arenas and as I intend to demonstrate, happens to Sita.

A brief and straightforward example is the use of Sita as inspiration for women to enter into Indian politics during the nationalist movement circa 1930 (think Gandhi). As explained by the scholar, Stephanie Tawa Lama in the International Review of Sociology, what she calls the “Hindu Goddess” (used here as a blanket name for the “main or typical” goddesses of Hinduism) is manipulated to suit many situations. In the case of Sita, Lama explains that Sita is “deliberately construed as a role model for women to engage in the nationalist movement”(7). But instead of acting solely as a guardian for strong females, she is portrayed as having strength by fulfilling her dharma as goddess, wife, and princess. To quote Lama once more, “the invocation of the Goddess legitimizes people’s participation in the movement”(8). While the cause of incorporating women into all spheres of life is admirable, the submissive and passive aggressive nature of Sita may prove to be less than ideal for women hoping to stand up for themselves politically. However, it is exactly within the manipulation of Sita (i.e. ignoring her passive and accommodating personality and to focus on her ability to fulfill dharma) that causes her to become a role model for Indian women interested in entering the political forum.

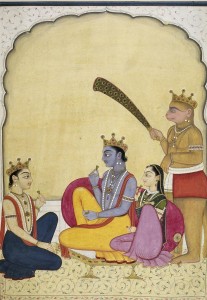

Rama and Sita with Lakshmana and Hanuman. Ink and opaque watercolor on paper. 1765. The American Council for Southern Asian Art Collection at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. ArtStor http://www.umich.edu/~hartspc/acsaa/index.html. November 20, 2014.

As the pendulum swings so does the portrayal of our dear Sita. On this occasion we are presented with a case in which Sita is employed as the epitome of docile womanhood (an application that I can readily understand having read Valmiki’s Ramayana). In this article by Devdutt Pattanaik, he explains a literal interpretation of Sita’s encirclement upon Lakshmana leaving her in the hermitage to follow Rama’s cry from the forest leading to Sita’s kidnapping by Ravana (I would want a golden deer, too, Sita). In the scenario exhibited by Pattanaik in “Threshold of Chastity,” he demonstrates the way in which some use Sita’s “indiscretion” (i.e. feeding a starving beggar who approaches – as her dharma commands) as a warning to all young brides to never cross their threshold. In an interpretation almost too extreme to understand, I can only quote the author, “[A bride] may ‘cross the threshold’ only twice in her life: once as a bride on the way to her husband’s house and the second time as a corpse on her way to the crematorium” (22). If you, like me, are shocked and thinking, “No one stays in her home all the time,” there is still some glimmer of hope. The author goes on to explain that any other outing must be “chaperoned” and that “’stepping out’… brings disgrace to the household!” If this is not startling enough, an analysis of the situation might conclude that according to Sita’s dharma, she has to feed anyone who approaches her begging for food. This makes her fate impossible to avoid (damned if you do, damned if you don’t – literally). How is it then, that Sita can be blamed and even condemned for crossing the line Laksmana made to feed a hungry hermit? This manipulation of Sita’s story seems so far from Gandhi’s manipulation of Sita’s persona. We’ve gone from the nationalist movement using Sita as an example of strength to masogonists using Sita as a warning for all insubordinate women.

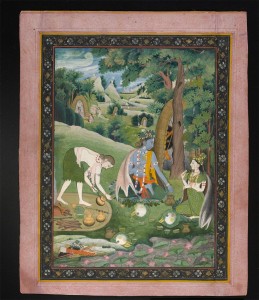

Rama, Lakshmana, and Sita Cooking and Eating in the Wilderness. Gouache with Gold on Paper. 1820. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Artstor. www.mfah.org. November 20, 2014.

It appears that even translations or the way that one reads the text can lack consistency in the portrayal of Sita as well. Sally J. Sutherland writes in an article entitled Sita and Draupadi: Aggressive Behavior and Female Role-Models in the Sanskrit Epics statements that do not exactly match my read of Valmiki’s Ramayana. For instance, in reference to the moment in which Sita encourages Ram to retrieve the golden deer for her (again, it is a golden deer, who can be expected to only watch it run by?), Sutherland exclaims that the consequence is that we are reminded of Sita’s “strong will” as “her most striking trait” (75). However, as I expressed previously, I find Sita’s character to come across as submissive and only find her to be passive aggressive with the conclusion of the epic, though Sutherland acknowledges this as a significant moment of passive aggressivity, she expresses feeling that way elsewhere in the story. Sutherland and I interpret differently again in reference to the end of the epic when she considers Sita and Ram’s relationship as feeling “resolved” (78). On the contrary, I find it difficult to come to any understanding or settled feelings with the conclusion of the epic. Sutherland also goes on to explain that Sita’s action of essentially killing herself is “one socially acceptable manner of expressing [disaffection or disloyalty]” and describes it simply as “masochistic actions, actions turned against the self as a form of revenge against the aggressor” (78). I find these statements to be unnerving and a little far-fetched. Would Sita’s final act be as impressive if this was just something that passive aggressive people did generally? However, Sutherland concludes her paper with a feeling that masochism is a normative part of society.

While no person, figure, character, or idea is straightforward and clear cut, there is a way in which religious figures can be disassembled and then put back together to suit someone’s momentary needs. So, I pose the question in conclusion, how do we truly understand Sita when so many factors are biased? How do we sift through all of the manipulation to find the true person/goddess?

WORKS CITED:

Lama, Stéphanie Tawa. “The Hindu Goddess and Women’s Political Representation in South Asia: Symbolic Resource or Feminine Mystique?” International Review of Sociology Vol. 11, No. 1 (2001): 5-18. Web.

Pattanaik, Devdutt. “Threshold of Chastity: The line that must not be crossed.” Parabola (Spring 2000): 19-26. Web.

Sita’s Ordeal by Fire, From a Ramayana. Ink and color on paper. 1600. The American Council for Southern Asian Art Collection at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. ArtStor http://www.umich.edu/~hartspc/acsaa/index.html. October 12, 2014.

Sutherland, Sally J. “Sita and Draupadi: Aggressive Behavior and Female Role-Models in the Sanskrit Epics.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 109, No. 1 (Jan-Mar., 1989), 63-79. Web.

Rama, Lakshmana, and Sita Cooking and Eating in the Wilderness. Gouache with Gold on Paper. 1820. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Artstor . www.mfah.org. November 20, 2014.

Rama and Sita with Lakshmana and Hanuman. Ink and opaque watercolor on paper. 1765. The American Council for Southern Asian Art Collection at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. ArtStor http://www.umich.edu/~hartspc/acsaa/index.html. November 20, 2014.

Valmiki. Ramayana, trans. William Buck (Berkeley: University of California Press), 1997, 363-366.