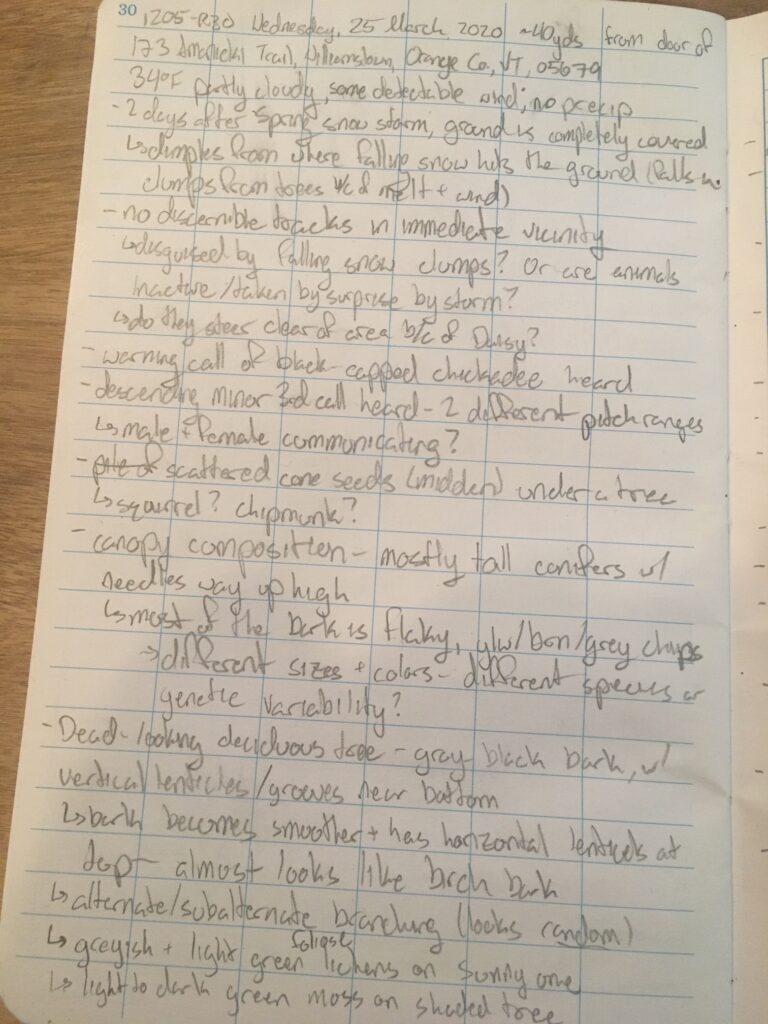

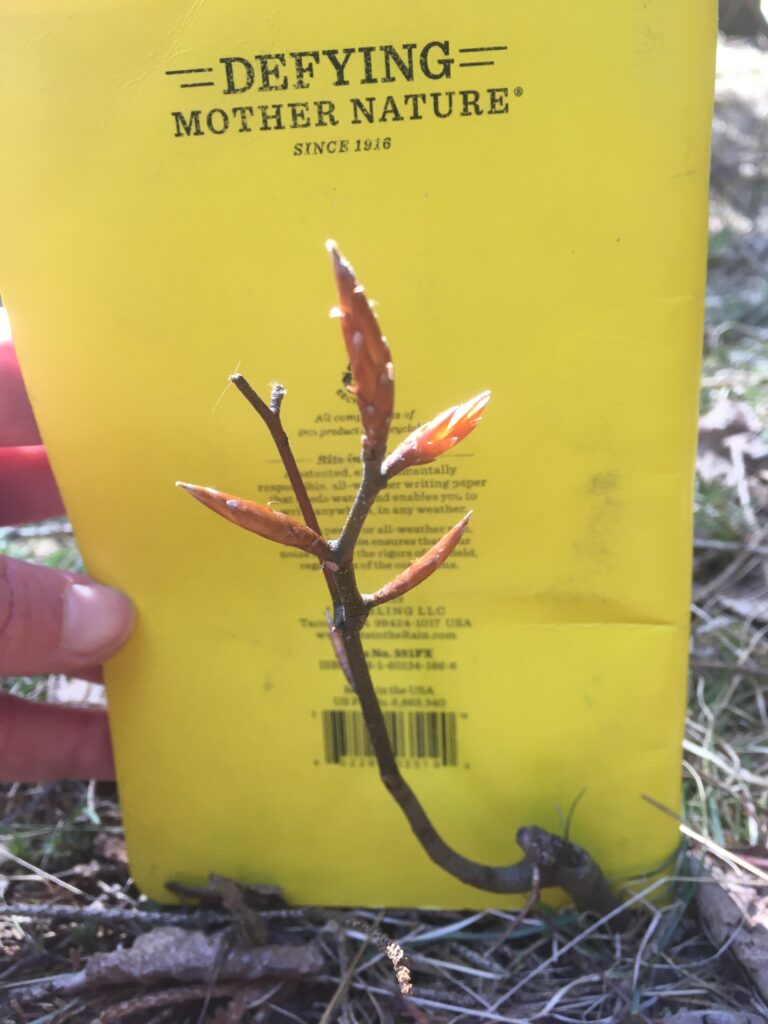

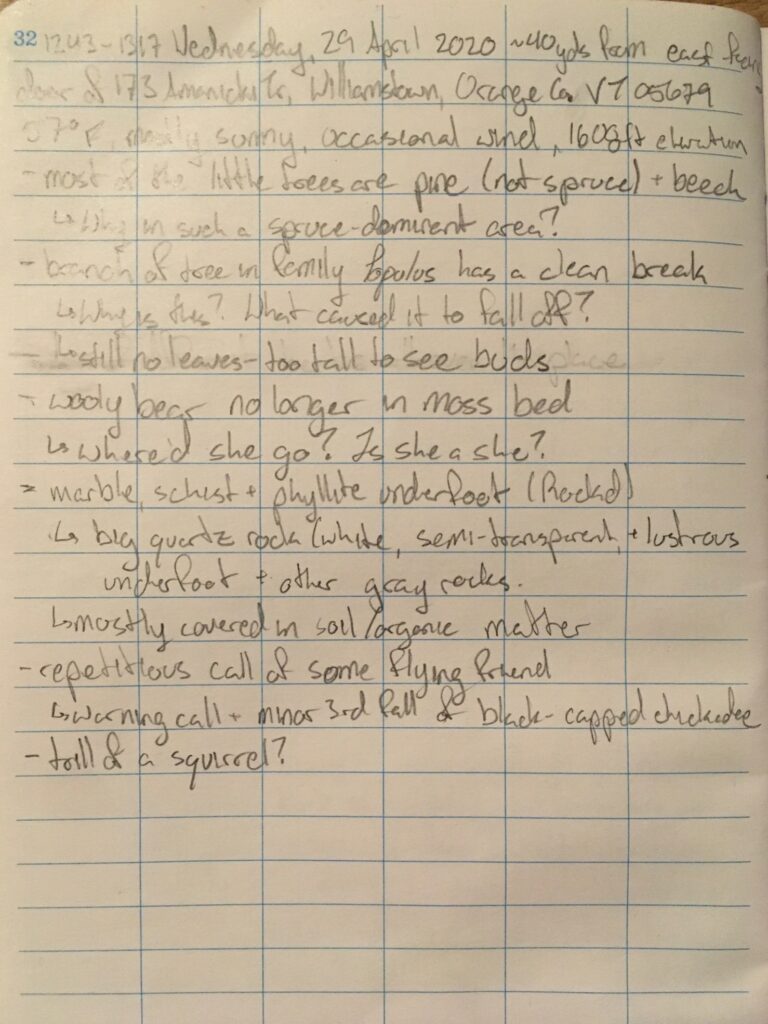

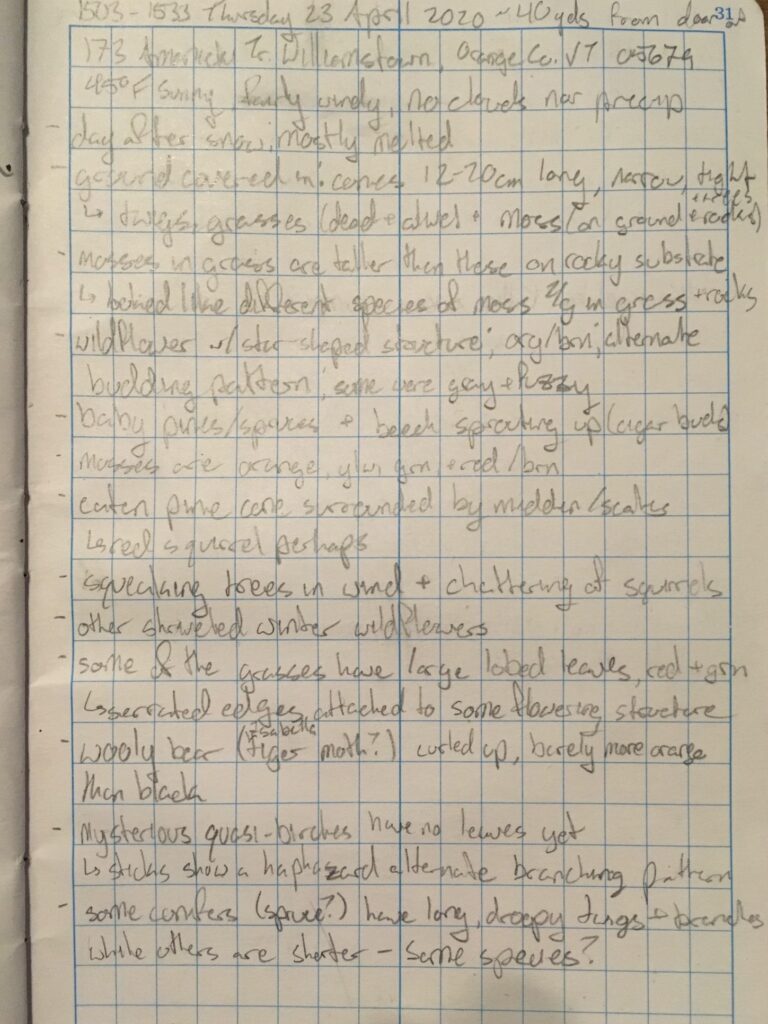

Without any snow cover in the immediate area, I can now see the cones, twigs, saplings, mosses, and other ground cover, dead and alive. Notably, there is an abundance of spruce cones on the ground, ranging from 12-20cm (fig. 1). Some are stripped of their scales, however, likely the work of some small mammal (fig. 2). Long cones, singly attached, non-prickly needles, and droopy branches indicate that the surrounding trees are Norway spruces (Picea abies); I haven’t seen any other cones indicating the presence of other spruce species (Arbor Day Foundation, n.d.). The enigmatic, somewhat birch-like trees observed in March have not yet leafed out, nor can I see any buds from where I was standing; the branches are very high up. With the help of iNaturalist, I can more confidently place these trees within the genus Populus (California Academy of Sciences, 2008). Further research has suggested that they are white poplar (Populus alba), an invasive species in Vermont, but they may also be some species of aspen (Vermont Invasives, n.d.). Hopefully I can identify these trees with more certainty once they bear leaves. Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia) saplings are also frequent in this immediate area, yet most are no taller than a foot or two currently. The beech saplings are showing their long, pointed buds (fig. 3). I haven’t noticed any changes to the trees between last week and today.

Lots of different herbaceous organism cover this woodland floor; I don’t think I’ve never noticed nor appreciated how much diversity and co-existence there can be among the organisms in a relatively small area. Among the crowd stands a few stalky withered flowers. One is quite tall and branches extensively, ending in clusters of hollow-looking, star-like structures; some of these are covered in a gray fuzz (fig. 4). Another herbaceous plant has red/green serrated leaves in pairs of two at each leaf node, and at some nodes a pair of stalks bearing withered flowers are attached (fig. 5). There were no noticeable changes in these plants between last week and today. It will be interesting to see what happens to these apparently withered plants as spring turns to summer.

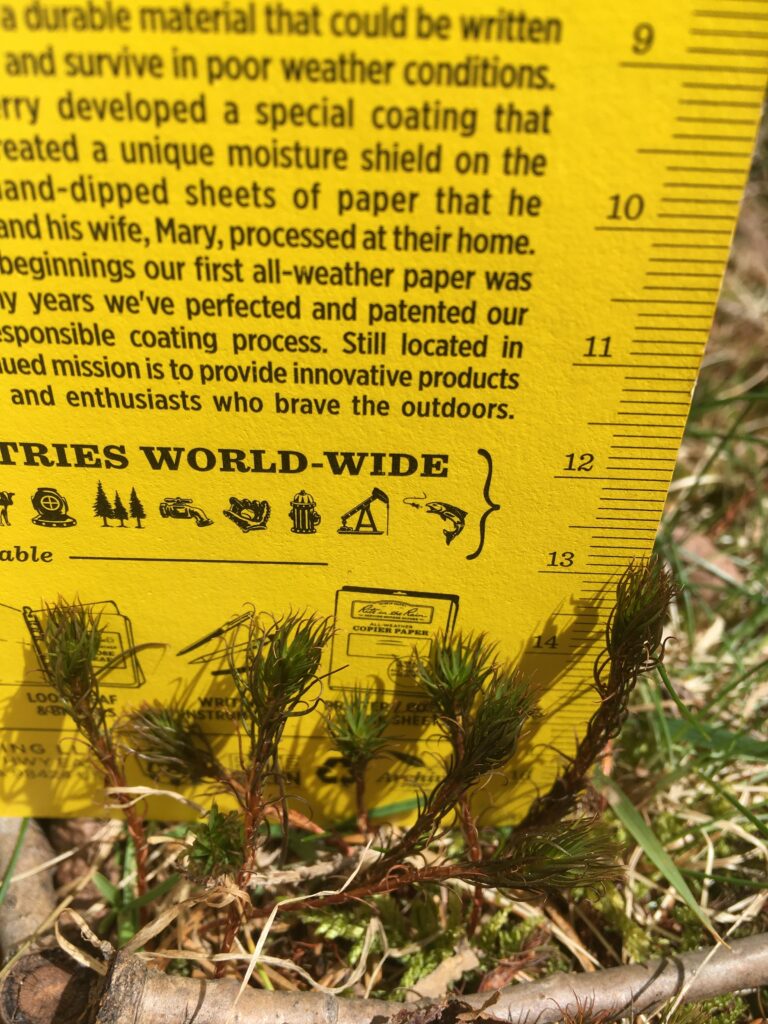

A mosaic of mosses also dominates much of the ground cover and creeps up some of the nearby trees. The mosses in the deeper soils look taller than those on nearby trees and rocky substrates. These mosses are orange, yellow, and many shades of green. One of the mosses in the soil is dark green and seems a bit taller than most of its neighboring mosses (fig. 6). iNaturalist classified it as some type of aloe moss (family Polytrichaceae), but it dosen’t look like its whorled leaves are splayed out like they appear to be in other photos of this family of moss (California Academy of Sciences, 2008). I wonder if these moss’s leaves will unfurl with time, like a flower blooming.

Among the moss was an Isabella tiger moth caterpillar (Pyrrharctia isabella), known commonly as the woolly bear, curled up on its side; it was almost equal parts black and orange, with slightly more orange (fig. 7). According to Yankee legend, the ratio of orange to black on woolly bears is a predictor of the severity of the coming winter, with more black being indicative of a longer, harder winter (Holland, 2010). If anything, woolly bears’ coloration is more telling of how short the last winter was; an earlier spring gives woolly bears more time to eat before hibernating for the winter and the more it can eat, the more it grows. This growth results in the caterpillar being more orange than black (the sections of its body which grow during this time produce orange bristles) (Holland, 2010). I spotted this little guy last week, but he wasn’t there today.

References

Arbor Day Foundation. (n.d.). What tree is that?. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.arborday.org/trees/whattree/index.cfm

California Academy of Sciences. (2008). iNaturalist (Version 2.8.7) [Mobile application software].

Holland, M. (2010). Naturally curious: A photographic field guide and month-by-month journey through the fields, woods, and marshes of New England. North Pomfret, VT: Trafalgar Square Books.

Vermont Invasives. (n.d.). White poplar. https://vtinvasives.org/invasive/white-poplar