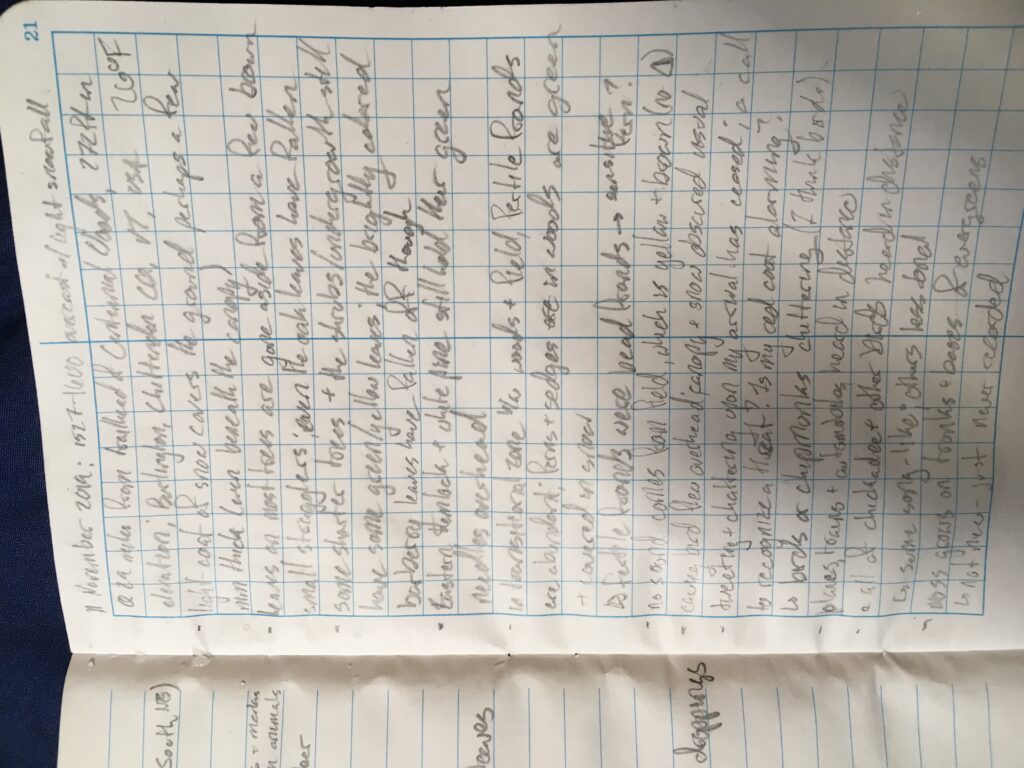

The characteristics of a geographic area and the experiences one has there often contribute to one’s sense of place, that is, the connection between a person and an area of land. At the Projection, I find that the phenological changes I observe correlate to my own knowledge of biology, ecology, and history. I continue to learn from this area in Centennial Woods as it changes throughout the seasons and each visit is reflective of the new knowledge I gain from books and lecture. For example, just today I took note of fertile fronds, the reproductive structures of ferns like sensitive ferns which lack sori (spore-bearing structures) on the underside of their fronds. As I continue to visit the Projection, I become more attentive to the organisms and natural characteristics of the place, and the Projection becomes more integral to my learning of phenology.

Sense of place can also be described at different scales. Alone, I feel that the Projection and my visits are a piece of my experience as a student at UVM; they contribute to my pursuit of knowledge and familiarity with the area. Sometimes, the associated solitude also brings a reprieve from the bustle of campus. However, when I sit there and listen, I can hear planes fly overhead as well as nearby traffic and other machinery. This reminds me that Centennial Woods is a place not just within my UVM experience, but my experience as a Burlington resident. When juxtaposed, I feel a looming sense of obligation and stress when I trek through the woods in search of signs of life, often not knowing what to look for or what I am looking at (and hearing). In contrast, I tend to associate my off campus/downtown experience with recreation, free time, and company. Altogether, these two sides of the “Burlington Resident” coin (my student life and social life) are a piece in my sense of place within the entire state (in which I was raised). Right now, Burlington feels like a densely populated urban center full of opportunity, independence, and new experiences (including those in Centennial Woods). In comparison, my hometown (Williamstown, VT) feels small yet significant, and the time I spend in Centennial Woods is slightly reminiscent of my experiences in the woods in my backyard. As a part of Burlington, Centennial Woods is an allusion to home, and my familiarity/experiences in both Burlington and Williamstown comprise parts of my experience and sense of belonging in the state of Vermont.

How societies and different people value a place may vary across cultures and time periods. Such is the case with Centennial Woods. Historically, Centennial Woods wasn’t always a natural area nor was it valued for its ecological importance. Prior to deforestation and settlement by European settlers, the land where Centennial Woods now stands was likely all forested and used by the Abenaki Native Americans for subsistence. The Abenakis viewed the land as a living entity with which giving was just as necessary as taking. The Projection, if it existed as it does now, likely would be appreciated more spiritually than it was later in history. However, as Europeans pushed the native peoples out of the area, the land was simply viewed as a supply of commodities made for pillaging; deforestation for pastureland and timber ran rampant throughout the state. This unbridled utilitarian view, which began with European settlement in the 18th century and ran well into (and beyond) the 20th century was checked by conservationist movements beginning in the early 20th century. Centennial Woods was eventually recognized as a natural area after it was bought by UVM. However, before UVM made a deal with the Vermont Land Trust to not develop the land, Centennial Woods was not treated as a natural area. The land UVM had acquired shrank to make way for development of other buildings and parking lots on campus, and was a site for dumping fill material, oil, and even cadavers from the hospital. While it seemed as if Centennial Woods was valued for its natural beauty and use for recreation, it was still seen as a commodity for human use. Today, now that the land cannot be developed except under special circumstances, Centennial Woods is wholly a place for recreation and academia for the community. Throughout its history, Centennial Woods’ meaning as a place has clearly changed numerous times.