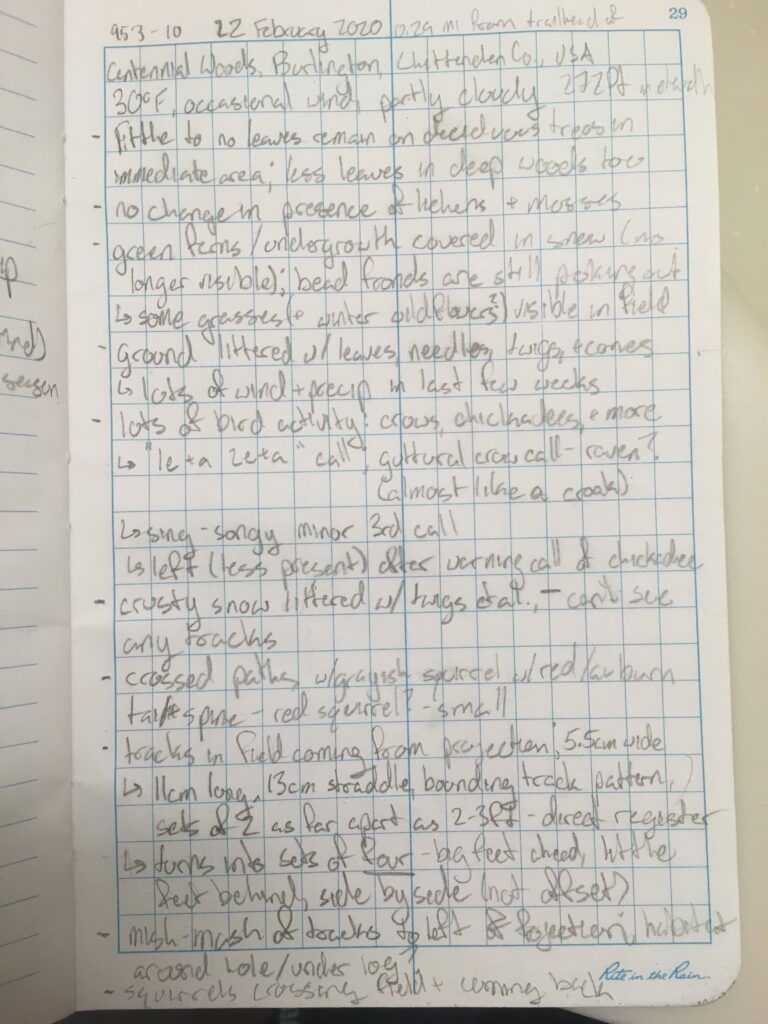

There seemed to be few phenological changes since my last visit to the Projection in January. On this warm February day, the lichens and mosses still clung to the trees, bright green in the morning sun. The trees in the immediate area were still bare of leaves, and deeper in the woods, the old, crinkly, brownish-green leaves which hung on to some deciduous trees were fewer in number and have since turned a reddish-brown hue; many of the greenish leaves could be seen on the ground. In fact, the snow was littered with twigs, leaves, needles, and cones from the trees above. I suspect this was a result of the high winds we’ve been experiencing this week as well as the large amount of precipitation which has fallen over the past month. The green ferns I saw in January were buried by the snow this time around, but the fertile fronds still poked through; I also saw goldenrod (genus Solidago) in this area (fig. 1) (California Academy of Sciences, 2008).

While the snow in the immediate area was too crusty and debris-littered to capture any tracks, in the fielded area nearby I found a set of side-by-side footprints which looked as if a bounder had come through; there were only two prints (fig. 2). The straddle of the tracks was 13cm and the length of the track itself was 11cm. The distance between tracks varied but was as great as 2-3ft by my estimate. However, as I followed the tracks further across the field, I saw they actually occurred in sets of four, and that what I had taken for as a bounder was in fact a hopper with a set of the larger tracks preceding a smaller pair lined up side-by-side (fig. 3). With this information, the tracks likely belonged to a gray squirrel (Levine, 2014). These tracks led all the way across the field and into the woods, where I was deterred from my pursuit by the warning calls of black-capped chickadees.

Also near the Projection was a mess of tracks which I presumed belonged to a squirrel(s); once again the tracks consisted of two large feet preceding to smaller feet (Levine, 2014). However, some sets of tracks contained anywhere from 2-5 footprints, suggesting that there was more than one squirrel, or that one squirrel was running all over the place or moving in an irregular manner (fig. 4). In this area I saw tracks under a fallen tree which had made a little covered area in which I would imagine some squirrel(s) would den up (fig. 5). I also found a hole in the ground nearby, which was likely an entrance to subnivean tunnels (fig. 4) (Holland, 2010). After seeing a red squirrel in the area during this visit, determining that the tracks were those of a squirrel, and finding out that red squirrels commonly make subnivean tunnels, I would imagine that the prints and potential dens belonged to a red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus). Red squirrels remain active in the winter and commonly live around conifers in which they can make nests called dreys (Holland, 2010; Vermont Center for Ecostudies, n.d.). These critters will also eat sap and conifer seeds, often storing the latter for consumption during the winter (Holland, 2010). While red squirrels are primarily satiated by conifer seeds, they also eat berries, mushrooms, and bird eggs, as well as the nestlings of birds including Bicknell’s Thrush in some habitats (Vermont Center for Ecostudies, n.d.). Red squirrels are diurnal (active during the day) and are most active in the early morning and late afternoon (Vermont Center for Ecostudies, n.d.). Predators of the red squirrel include birds of prey, coyotes, foxes, weasels, and bobcats (Holland, 2010).

There were also many birds out and about, singing and cawing on this day. However, once I reached the Projection, I heard the warning call of a black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) and soon the sounds of birds became more distant (M. McDonald, personal communication, February 6, 2020). I also heard the cawing of crows as well as other interesting calls, but I could not identify nor see the callers more often than not.

References

California Academy of Sciences. (2008). iNaturalist (Version 2.8.7) [Mobile application software].

Holland, M. (2010). Naturally curious: A photographic field guide and month-by-month journey through the fields, woods, and marshes of New England. North Pomfret, VT: Trafalgar Square Books.

Levine, L. (2014). Mammal tracks and scat life-size pocket guide: Tracking through all seasons. East Dummerston, VT: Heartwood Press.

Vermont Center for Ecostudies. (n.d.). Red Squirrel. https://vtecostudies.org/wildlife/mammals/red-squirrel/