UVM technology leaders and staff are monitoring the news around emerging global cybersecurity threats as a result of recent sanctions against Russia. We continuously engage with partners across Higher Education and in law enforcement to improve UVM’s defensive posture. As always, though, we need your help, and “the usual advice” is now more important than ever. Please…

…DO remain cautious of attachments and links that arrive via email.

About to click a link? Where does it go? Is the attachment from someone you know, or is it something you’re expecting? If not, and it’s practical to ask the sender via some other channel (phone? Teams?), do that. When in doubt, contact iso@uvm.edu for help. In the business of dealing with lots of attachments? Make sure you’re running current anti-malware protection. Having your devices managed makes this easy.

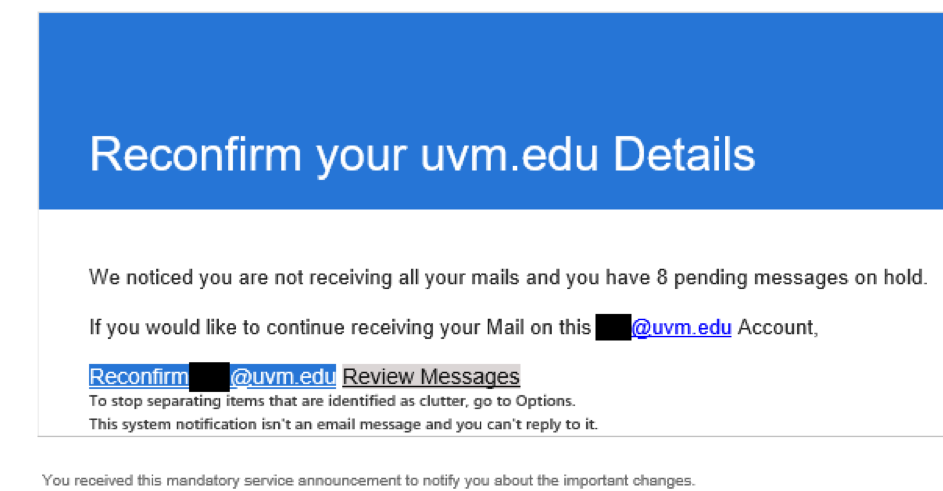

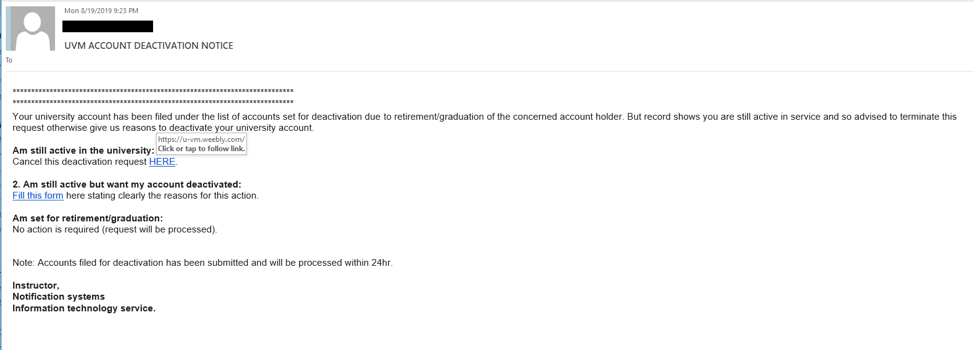

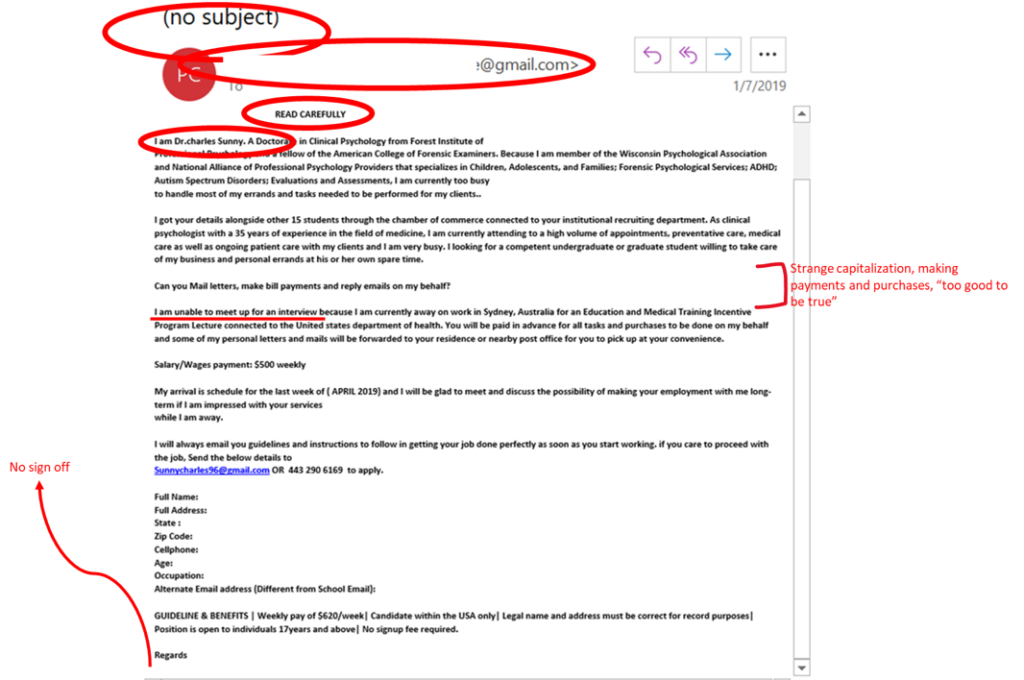

…DO be suspicious of any message demanding that you “verify your account” or otherwise provoking you with a sense of urgency.

Is the message threatening dire consequences for your digital access to UVM if you don’t act? It may be phishing: a social engineering attack designed to steal your access and your information (or UVM’s). Social engineering is a component of many major intrusions and breaches, and successful phishing makes it easier for attackers to succeed. Don’t make it easy for them to succeed. You can do your part to slow them down by making sure you only ever use your UVM credentials to access legitimate UVM sites. Need help determining what those are? Contact your technical support provider (ETS Client Services or LCOM Technology Services) for more assistance.

…DO be skeptical of unfamiliar errors arising on your computing devices.

Did an unusual error just pop up on your computer or mobile? Does it sound threatening or ominous? Does it contain a “click here for assistance” link or a phone number to call for help? Make a note of the exact error (write it down, take a screenshot, take a photo), and contact ETS Client Services or LCOM Technology Services. If there’s really something wrong, we can help. Sometimes, though, this is the result of “scareware” — an effort to frighten or intimidate you into paying money for snake oil tech support, or worse yet, allowing malicious parties to install software on your computer and remotely control it (see below).

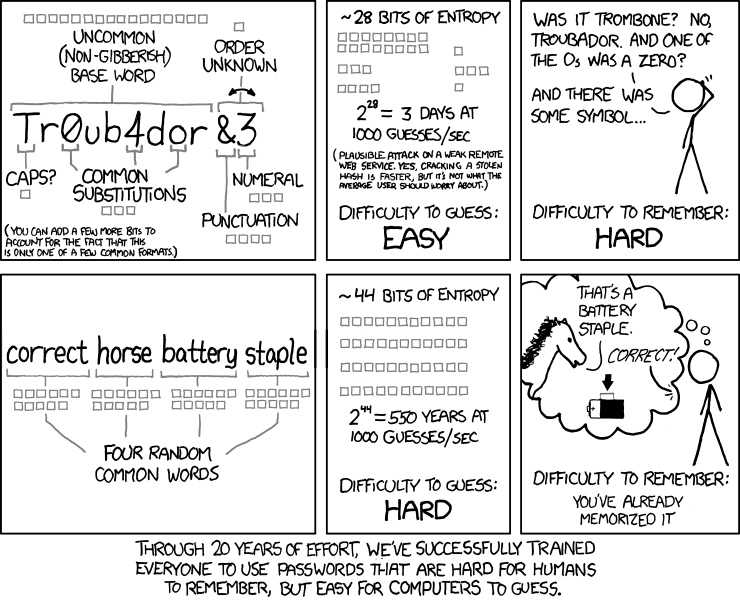

…DO keep your computers and mobile devices up-to-date with the latest patches to operating systems and applications.

Computers run software, and software has flaws. All of it. The best thing we can do to protect ourselves from people trying to turn those flaws to their advantage is update our software when its flaws are found and patched. The operating system (OS) on all computers and mobile devices should be set to automatically update. Ditto all the applications or mobile apps in use. It’s especially important to keep any software that will interact with data from the internet — web browser, email program, productivity apps (we’re betting most of those attachments coming in via email are Word/Excel docs and PDFs), media players — current. Likewise anything you’re relying upon for security; most anti-malware tools rely at least in part on threat information collected by the vendor, so it’s critical to keep feeding that info into those tools as it’s made available. Again, ETS’s computer management is your friend.

…DO NOT allow anyone other than approved UVM support staff to remotely control any computer with access to UVM systems and data.

A “Tech Support attack” is particularly insidious, as it can result in directly granting the attacker access to your computer or mobile device. It generally starts in one of two ways: either they contact you, or you contact them.

In the former case, you get a phone call from someone purporting to be from a well-known company (Microsoft, maybe?) who claims that your computer/mobile has been observed doing something harmful on the internet, and they can fix it for you.

In the latter, an otherwise-innocuous piece of software or web page pops up a serious-looking error designed to prey upon your anxiety. Maybe it says your computer is somehow broken; maybe it claims to have found a terrible virus. But! It offers a way out! “Help” is available if you call the number presented on the screen.

Either way, when they call you or you call them, the person at the other ends asks for payment via credit card, and then they frequently require that you install special software on your device in order to fix the “issue”. The cursor moves around, some buttons are clicked, and they assert the “problem” is fixed. In all likelihood, there was nothing wrong. But there is now. The software they wanted installed allows them to remotely-control your device and/or copy your private data (or UVM’s private data) off the device so they can sell it or use it to extort money. They may even leave a parting gift of ransomware, adding insult to injury.

…DO ask questions if you’re unsure about an online interaction.

ETS’s Information Security Office exists not only to protect UVM, but to help UVM’s community protect itself. There are no “stupid questions”, and the increased sophistication of modern cybersecurity threats means that anyone could fall prey to attack. We’re here to help and teach, not to judge. Please feel encouraged to reach out with your questions or concerns by emailing iso@uvm.edu.

In this time of heightened tension, let’s act early on anomalies — unexpected “urgent” emails, novel errors, unexplained reboots. It’s easy to write these off as being the same little bumps in the road that have always existed in online life, and most of them are. Spotting the truly important ones is going to require each of us to be on the lookout. Computer did something weird? Check your gut, then get in touch if needed.

OK, there is something new…

Disinformation and misinformation online are a recognized threat at many levels. While differences of opinion and interpretation are the hallmarks of a vibrant intellectual community, there’s no place for bad-faith misdirection and outright lies. Our law enforcement partners have asked for early warning of disinformation and misinformation campaigns observed by our communities, especially in social media platforms. Please reach out to iso@uvm.edu if you observe something concerning in this vein.