In May 2015, the Chittenden, Buckham and Wills Residence Hall Complex was removed. Replacing it in August 2017 will be a new first year residence hall with a 450-seat dining hall, a gym complex, and a bridge to the Bailey/Howe Library. Behind the Cook Physical Sciences Building, they are currently building the Discovery Building, which will be “a state-of-the-art teaching and research laboratory facility,” according to the UVM Construction website, which is the first of three phases in the construction of an entirely new STEM complex as well as renovations to the Votey Building. Today, these areas are simply construction, barely representing what they one day will be. These construction sites are a part of every UVM student’s everyday life, whether it causes a longer walk to class through the detours, or if the sound of the construction is the background to one, or every class. Due to the undeniable effect that the construction sites have had on the lives of current and prospective UVM students, especially freshmen who have never experienced UVM without the construction, and prospective students coming to look at the school for the first time, the construction is dominant in the soundscape of UVM. One of the things that sets the construction sites apart from the other soundscapes of the university is the fact that this soundscape is temporary, and it is constantly changing. The sounds of this construction can be heard from all around Central Campus, and it seems as if anywhere you turn there is construction.

The construction site is incredibly diverse in its heavy industrial sounds and has become central to UVM’s soundscape. The site provides a vastly different experience depending on where you are positioned around it. The keynote sound of the construction site from where I stood against a concrete barrier that read “S D Ireland,” was the constant, unignorable low rumble of machinery. Such a rumble sounded so familiar, yet I couldn’t quite locate what was making the sound. By the end of thirty minutes of listening to the construction, that low rumble became white noise– it was still there, yet I did not notice it. Rather, it was the background to the plethora of other sounds that fought for my attention: the beeping of massive trucks backing up, warning anyone within earshot that it was on its way, and it wasn’t stopping; the deliberate picking up and dumping of gravel into the backs of these trucks; the rev and grumble of the engine as it worked to move tons of weight to the next place it needed to be in the seemingly chaotic, yet simply the byproduct of the system of the construction site.

The construction site is what R Murray Schafer describes as “noise pollution” in the article “The Soundscape.” Many believe that “noise pollution” is perhaps the noises of things that are harmful to humans and the earth, such as the sounds of cars speeding on a freeway. However, when Schafer discusses “noise pollution,” he’s referencing his fears that man-made, destructive sounds are disrupting the natural sounds of the earth, and that humans have learned to tune out such sounds that allow them to appreciate the soundscape of their entire environment. When it comes to this construction site, and arguably all of UVM, Schafer is correct. As I stood by and watched the construction site, one of the most striking things I noticed was the lack of noise when students were walking to class. Many were with other people and carrying on conversations, but just as many, if not more, walked in silence– their headphones barring them from hearing, and possibly even noticing the construction, as well as all of the other sounds surrounding them.

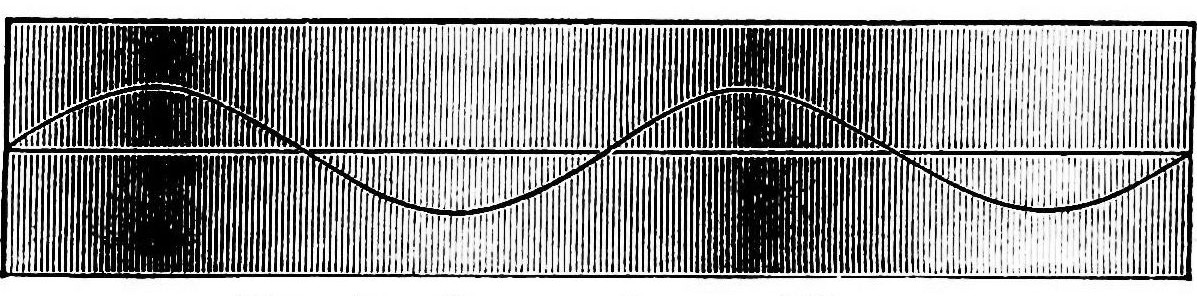

Outside the back entrance of the Cook building, the construction seemed at its loudest. By far the most dominant sound present was the machine drilling the beam into the ground, which emitted a deep vibration. The vibrations swelled and got louder at certain times, so that you could actually feel the vibrations in your chest and beneath you on the steps you were sitting upon. This exhibits Trower’s idea in her article “Senses of Vibration” relaying how sound is made up of vibrations which can not only be audible, but physical, and thereby transcend our senses as well as contribute to our experience of a sound. The occasional spraying of gravel, high pitched beeping of trucks backing up, and rhythmic clanking of the chain fence that surrounds the site accented the drone of the drilling machine. The most dominant sound is simultaneously the most important sound for the soundscape because it was constant throughout my entire experience at the construction site.

The construction represents our society’s culture of constantly building things up, innovating, and creating. The sound at this site demands your attention and has profound social implications. The construction site generally has a negative reputation among students and faculty alike because the sound is immensely distracting and loud. The drilling, beeping, high pitched screeching, among other sounds, inhibit interactions between people because the sound is often too overpowering to continue conversations between people passing by, as well as infiltrates the classrooms that surround the site. However, Schwartz in his article “Making Noise” would argue that though this sounds are unwanted, they are no less significant in creating the soundscape. Though people are forced to hear the sound of the construction site as they walk by, it is rare that they actually listen to it–it usually blends into one noisy mess. Personally, it wasn’t until I was forced to sit down and focus my attention on the site that I actually recognized certain machines and the noises they were making. However, even though I was able to identify the sounds, it’s hard to attribute any sort of meaning to them because you typically don’t really have an understanding for what that machine is, and what its role is at the construction site.

This soundscape composition is a construction site all in its own. By taking apart the amorphous soundscape of the original site, and piecing together a collage of construction noises, a new construction site was effectively born. The reason I chose to arrange this piece in a manner that lacks rhythm, or any other apparent premeditated order, is because of the profound beauty I beheld while listening to the original construction site. But to behold was not enough; I wanted to beget. I wanted to create a construction site of my own, and to do that, I needed to have that rumbling drone of machinery, that beeping of backing-up vehicles, the random slamming of metal against metal, all besprinkled with an occasional screaming buzz saw. Similarly to some of Monacchi’s Eco-Acoustic music, a sense of place was created without actually having the noises arranged in their recorded order. In stark contrast to his message, however, this soundscape conveys the brilliant power of industry. Monacchi’s message is “save the rainforest,” while my message is “celebrate humanity.”

– McKenna Murray, Elle Cunningham, Kyle Weinstein