Healthcare & Traditional Medicine

The Role of Religion in the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction and Background:

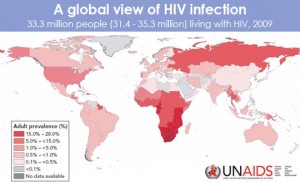

The number of people living with HIV worldwide has increased exponentially since the 1980s and as of 2004, over 20 million people had died of AIDS. Already, HIV/AIDS is the most devastating epidemic thus far and is often referred to as “the deadliest in the history of humankind” (Abdool Karim, Abdool Karim, 2005:31). Today, Sub-Saharan Africa remains the world region most affected by the HIV epidemic. UNAIDS (2011) reported that as of 2009, out of the total number of people living with HIV worldwide, 34% lived in this region. This paper will draw on examples from South Africa’s HIV epidemic. In 2011, an estimated 5.6 million people were living with HIV in South Africa. In addition, 17.3% of all adults ages 15-49 are infected and a total of 5.1 million South Africans ages 15 and up are living with HIV. Over 270,000 deaths due to AIDS occur in South Africa each year and in 2011 there were 380,000 new infections in this one country alone. These statistics make South Africa the country with the largest number of people living with HIV today (UNAIDS, 2011).

This paper will specifically discuss religion’s role in the HIV/AIDS epidemic in South Africa. Undoubtedly, some religions have influenced the rapid spread of infection in this region. This essay will explore both the ways in which religions such as witchcraft and Christianity in South Africa contribute to the decreased use of preventative measures to protect against HIV and the increased prevalence of stigma surrounding the disease. In addition, some traditional religions in Sub-Saharan Africa promote traditional methods of healing instead of modern medicine, which has proven to be significantly less effective, therefore contributing to the high rate of new infections each year. Witchcraft, Christianity and traditional methods of healing as a result of traditional religions are all contributing to the significant problem of HIV infection in Sub-Saharan Africa and play a detrimental role in the prevention, care and treatment in terms of HIV in this research.

This essay will discuss information provided by scholarly sources, many in the form of journal articles or books written by anthropologists and other experts on the subject of the HIV epidemic and traditional religions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Experts such as Adam Ashforth, Peter Delius and Robert Garner explore the ways in which religion impacts the HIV epidemic specifically in South Africa, which will be discussed in the first two examples of our essay. In addition, Jacob Homsy et al and Tonya Taylor’s research concerning HIV and traditional religions in Sub-Saharan Africa will be discussed when presenting the third example used to prove the thesis that religion does in fact play a detrimental role in the spread of HIV in this region. Many of the scholars cited in this essay have done research within countries such as South Africa and Zimbabwe, conducting personal interviews with HIV-positive persons, as well as with healthcare workers and religious leaders.

Example 1: “Witchcraft” in South Africa”

One specific example that will be used to discuss religion’s role in the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa is the effect witchcraft and the beliefs associated with it contribute to increased infections. A definition of witchcraft is: “…the manipulation by malicious individual of powers inherent in persons, spiritual entities and substances to cause harm to others” (Ashforth, 2002: 126). In a study of beliefs about HIV/AIDS in South Africa, 4% of those surveyed believe that AIDS is caused by witchcraft and 14% are unsure if it is caused by witchcraft (Kalichman and Simbayl, 2004: 573). Some believe that the HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa has become a “pandemic of witchcraft” (Ashforth, 2002: 122). One specific example of witchcraft in South Africa is the concept of “isidliso”, which is the poisoning inflicted by witches (Delius and Glaser, 2005: 34). This “poisoning” is often actually HIV infection, interpreted as “witchcraft”, which can only be cured by traditional or spiritual methods. Many South Africans seek care from traditional healers and take traditional medicines instead of those scientifically proven to prolong the lives of people living with HIV (Fairall and Wilson, 2005: 487). Instead of taking ARVs and treatments that have been proven to treat people with HIV, people miss out on the treatment and care they need, but also continue to spread the disease.

According to some witchcraft beliefs, curing HIV would mean expelling the disease, or the poison, from your body through sexual emission. Ashforth (2002) reports some men will go have sex with another women just to “expel” their witchcraft, then return to have sex with their girlfriend or wife. For obvious reasons, this contributes to the widespread infection of especially women in South Africa because not only are many wives and girlfriends affected, but other women as well (132). In addition to specific practices that are a direct result of beliefs that come out of witchcraft in South Africa, witchcraft leads to silence and discretion because no one wants to admit to their status. Being HIV-positive in the context of witchcraft in South Africa is embarrassing and potentially dangerous because it means they have been poisoned or cursed (Delius and Glaser, 2005: 34). No one wants to publicize the fact that they have been cursed, so they fail to reveal their status to anyone, including their sexual partners (Ashforth, 2002: 135). These stigmas that are a direct result of common beliefs about HIV within the context of witchcraft are contributing to the rapid spread of the disease not only in South Africa but throughout Sub-Saharan Africa in general.

Example 2: Christianity in South Africa

A second example that will be discussed to show the impact that religion has had on the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa is Christianity in South Africa. In South Africa, 80% of people identify as Christian and only 5% identify as other religions (Squire, 2007: 155). Garner (2000) reports that Christianity is the dominant religion in South Africa and half of South Africans attend worship once a week (46). Christian women are supposed to be submissive of their husbands, which many times, results in rare use of condoms because women do not have the power to insist upon safe sex (Pugh, 2010: 634). In addition, Christianity suggests that condoms promote promiscuity, which is frowned upon by the church. Churches feel that if the use of condoms is promoted, it will in turn promote premarital sex and extramarital sex, all things that are fundamentally opposed in Christianity (Pugh, 2010: 633). The ways in which Christianity effects the use of condoms in South Africa are clearly shown in Pugh’s (2010) article when she states, “I have heard men in Southern Africa say that they do not need to use a condom because in the end, it is only Jesus Christ who can protect them from getting the virus” (640). There is an obvious connection in South Africa between Christian beliefs and the low rate of condom usage in the country. The low rate of condom use is detrimental to the HIV epidemic in South Africa and contributes to the large number of new infections and the increased prevalence of the disease.

Example 3: Traditional Religion’s Role in Treatment Choice in Sub-Saharan Africa

The last example of religion’s impact on the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa is its role in choosing between available treatment options. There are two main types of treatment available to individuals affected with HIV/AIDS. There has been huge conflict between which treatment should be used in this region: traditional versus modern. In Africa roughly eighty percent of the population will consult a traditional healer in their lifetime. (Babb, et al. 314). One of the main reasons that dictates whether an individual will consult traditional methods over modern is how he/she interprets illness. Traditional medicine focuses on healing the infected physically as well as mentally and spiritually. A quote from an article on healing techniques in rural Zimbabwe describes traditional healing through use of an herb healer. “Through spirit possession and divination, the inyanga (traditional healer) transcends epidemiological explanations of disease by diagnosing its perceived social etiology, attempting to answer the more culturally (and/or personally) relevant question: why did this happen to me?” (Taylor, 2010). Traditional medicine is defined as the use of healing techniques through spiritual, botanical (herbs), and physical methods. Traditional healers believe that for one to be healthy, he/she must be in harmony with nature. Traditional medicine attributes illness to supernatural forces. It is believed that healers possess the abilities to repair one’s relationship with the supernatural world. Other than for religious reasons, traditional practices are preferred in that they are the most available, affordable, and the easiest treatment to access.

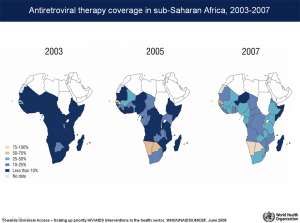

In contrast, modern medicine focuses solely on the physical treatment of a disease with treatment being based on observable signs and reported symptoms. It is defined by the use of antiretroviral therapy. At this time, this is the most effective type of treatment for HIV/AIDS. Therapy can dramatically increase the life expectancy of individuals infected with the disease through intense treatment of symptoms. Antiretroviral therapy is taken orally as a combination of two or more antiretroviral drugs. The combination is important as it prevents HIV/AIDS from becoming resistant to therapy, which is more likely to occur if one drug is administered alone. Together, the drugs suppress the HIV in the blood. It is most effective before the development of AIDS as these drugs keep the levels of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) low further putting off development of the disease. (Nachega, 2005)

Today, westerners are pushing for the integration of modern medicine into Sub-Saharan Africa. The most prevalent arguments against traditional medicine is that it is dangerous and unsterile and that traditional healers are not educated enough about HIV/AIDS in order to safely and effectively provide treatment. In a correlational study data was collected through interviews with 81 traditional healers in Botswana. The focus of the interviews was on seeing how much they knew about healthcare practices and more specifically HIV/AIDS. The results showed that the majority of traditional healers did not have access to sterile instruments. Though most encouraged the use of condoms they were unable to supply them to patients. Sixty percent of participants did not know the cause of HIV/AIDS. Fifty-nine percent stated that their main source of information was from the radio. (Homsy, 2004)

Besides spiritual reasons, individuals will favor traditional medicine over modern treatment due to high costs and low availability. In a cross-correlational study conducted in South Africa, researchers looked at the views and beliefs that exist about antiretroviral therapy. Through questionnaires, 105 patients were surveyed, 29% percent were using antiretroviral at the time the study was conducted. Ninety-eight percent of participants agreed that antiretroviral was effective in that it can stop the progression of HIV/AIDS. (Nachega, 2005) This shows that the people living in this region infected with the disease are aware of the effectiveness of this modern treatment.

The importance of religion in Sub-Saharan Africa affects the use of modern practices in the treatment of HIV/AIDs. With such a large role, it is one of the greatest influences on an individual’s decision-making and the interpretation of the disease. Spirituality is one of the main reason why the majority of those infected will choose traditional methods. It can be seen how religion inhibits the spread of information about modern treatment in this region. Without the integration of modern medicine, the HIV/AIDS epidemic will continue to be deadly and individuals will not receive the most effective treatment. Religion not only affects the spread of information about modern medicine but also general information about the disease. One qualitative study found through questionnaires that the majority of those religiously affiliated stated no intention or desire to changing their behaviors in order to prevent HIV/AIDS. The same study found that men who were religiously affiliated stated feeling less at risk to HIV/AIDS (Lagarde, 2000). Religion can facilitate the spread of information but research shows that it is not exposing individuals to the right information.

Conclusions:

It is important to understand that some of the literature discussed in this essay has limits to their research conducted. For example, there are ways in which religion has reached out to some people in Sub-Saharan Africa to promote safe sex practices as well as seeking testing, treatment, and care for HIV. This essay does not address the ways in which religion could also contribute to the prevention of HIV infection, especially due to the fact that many people are practicing in their religions in this region, whether it is traditional religions, Christianity or others. Limits to the sources cited in this paper also include the fact that they strictly address the ways in which traditional religions and Christianity prevent people from practicing safe sex and seeking the treatment they need if they are in fact HIV positive.

For the purpose of this essay however, through the specific examples of religion in South Africa, it is clear that some religions are contributing to increased infection and decreased prevention of HIV. Beliefs associated with witchcraft are contributing to stigmas surrounding the disease, as well as misunderstandings and misconceptions about how to prevent and treat the disease. In addition, Christianity in South Africa not only influences women to be submissive to their sexual partners, but also plays a detrimental role in the rare usage of condoms. This unsafe practice obviously contributes to increased infections not only in South Africa but also in all of Sub-Saharan Africa. Religion’s role in choosing treatment also adds to the deadliness of this disease, as infected individuals are not receiving the proper treatment. With spirituality as a driving force, traditional methods are more often chosen over modern practices. Modern medicine would be more prevalent in this region if religion did not act as a barrier to the spread of information about this treatment option and the negative characteristics of traditional healing.

Further Readings:

To understand better the urgency of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan African, visit:

http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/regions/easternandsouthernafrica/

http://www.who.int/gho/urban_health/outcomes/hiv_prevalence/en/

To watch a video that discusses the coexistence of modern and traditional medicine in Africa, visit:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nv8e950oZ-A

To watch a video of a Sangoma traditional healer, visit:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E6n3dFMBPQU&list=PLA046E298087E3E92

Works Cited:

Abdool Karim, Quarraisha ; Abdool Karim, Salim S.

2005 Introduction. In HIV/AIDS in South Africa. SS Abdool Karim and Q. Abdool Karim, eds. Pp. 31-36. Caimbridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ashforth, Adam.

2002 An Epidemic of Witchcraft? The Implications of AIDS for the Post-Apartheid State. African Studies 61(1): 121-143.

Babb, A. Dale, Pemba, Lindiwe, Seatlanyane, Pule, Charalambous, Salome, Churchyard, J. Gavin, Grant, D. Alison.

2007 Use of traditional medicine by HIV-infected individuals in South Africa in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Psychology, Health & Medicine 12(3): 314-320.

Delius, Peter ; Glaser, Clive.

2005 Sex, Disease and Stigma in South Africa: Historical Perspectives. African Journal of AIDS Research 4 (1): 29-36.

Fairall, Lara ; Wilson, Douglas.

2005 Challenges in Managing AIDS in South Africa. In HIV/AIDS in South Africa. SS Abdool Karim and Q. Abdool Karim, eds. Pp. 477-503. Caimbridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garner, Robert C.

2000 Safe Sects? Dynamic Religion and AIDS in South Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies 38 (1): 41-69.

Homsy, Jacob, King, Rachel, Balaba, Dorothy, Kabatesi, Donna.

2004 Traditional Health Practitioners are Key to Scaling up Comprehensive Care for HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 19(12): 1723-1725.

Kalichman, S.C. ; Simbayl, L.

2004 Traditional Beliefs about the Cause of AIDS and AIDS-Related Stigma in South Africa. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 16(5): 572-580.

Lagarde, Emmanuel, Enel, Catherine, Seck, Karim, et al.

2000 Religion and protective behaviours towards AIDS in rural Senegal. AIDS. 14(13): 2027-2033.

Nachega, B. Jean, Lehman, A. Dara, Hlatshwayo, Dorothy, Mothopeng, Rahcel, Chaisson, E. Richard, Karstaedt, S. Alan.

2005 HIV/AIDS and Antiretroviral Treatment Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Practices in HIV-Infected Adults in Soweto, South Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005. 38(2): 196-201.

Pugh, Sarah A.

2010 Examining the Interface Between HIV/AIDS, Religion and Gender in Sub-Saharan Africa. Canadian Journal of African Studies 44(3): 624-643.

Squire, Corinne.

2007 Living Positively: Religious and Moral Narratives of HIV. In: HIV in South Africa. Pp. 152-171. New York, NY: Routeledge.

Taylor, N. Tonya.

2010 “Because I was in pain, I just wanted to be treated.”: Competing Therapeutic Goals in the Performance of Healing HIV/AIDS in Rural Zimbabwe.” Journal of American Folklore. 2010. 123: 304-28.

UNAIDS.

2011 South Africa: HIV and AIDS Estimates. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica/ Accessed 10 March 2013.