Education & Development

Introduction:

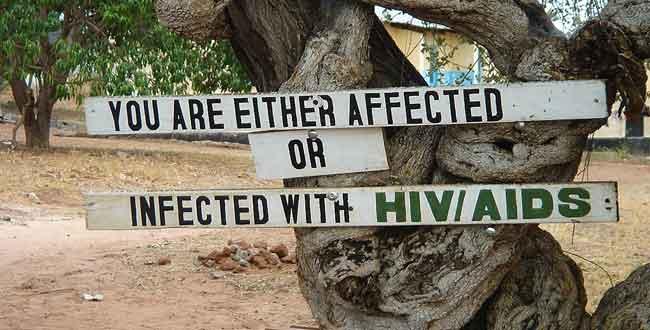

When exploring health in sub-Saharan Africa, it is impossible to not think about the ‘ education and development’ aspect of public health care. There are many factors at play regarding education and development, there are those factors that help development along and there are those that hinder it. In development research today, one will find that ‘women’s education and empowerment’ is the key to unlocking development in the third world, but just how can that be achieved? And what factors are at play to shape that? This paper will explore the factor of religion, in the education development discourse, what role does religion play in understanding, educating, or surviving AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa?

Background:

In this exploration of education and development in Africa, two countries, Nigeria and South Africa will be of focus. These were chosen because they provided many common variables in which cross-comparison could be done easily. South Africa and Nigeria are both former British colonies and both have a strong civil society in terms of infrastructure and religion. The country of Nigeria is split into regions with the north being primarily Muslims and the south being mostly Christian with some traditional religions mixed in certain areas. South Africa on the other hand, is a very diverse country due to the fact that it was once a settler colony for both the British and Dutch in the colonial period. Due to this diversity, South Africa has a wide dispersal of religion in different regions but like Nigeria, the big three, Christianity, Islam and Traditional religions are the most popular.

It is clear through this information that religion plays a key role in these societies. We will explore how religion has positively and adversely affected the education and development in the context of the HIV/AIDS crisis in these countries with the use several case studies. Before we delve into the education and development issues pertinent with the role of religion in the HIV/AIDS crisis, some topics relating to contraceptive use must be brought up for it is not possible to understand issues related to HIV/AIDs and social development without a context of contraceptive and family planning use.

Condom Use:

It was concluded through several case studies conducted in West Africa that religion does have an effect on a woman’s choice to use condoms, either as a preventative measure against HIV/AIDS or as a form of contraception. This is important to keep in mind in the face of development for, research shows that low levels of family planning use lead to higher birth rates which is a factor in underdevelopment. In a case study done in Nigeria, two researchers, Saddiq and Aguwa explore the role of religion in HIV/AIDS prevention in Nigeria with special reference to women. We see a recurring pattern of a war on condom use: churches feel like that cannot condone it and women feel like they cannot ask for men to use it. It is interesting to note that in Aguwa’s article, she expresses that the rates of HIV/AIDS are actually lower in the Muslim north because of their practices of repression of women, non-alcohol use and male circumcision (Aguwa 215). This is in contrast to Saddiq who advocates that the Muslim polygamous marriages in Nigeria are a factor in HIV prevalence rates. In these cases, polygamy leads to marriage dissolution. Not only is the husband sleeping with multiple wives but many times, the wives feel like they are not satisfied and seek extra-marital affairs as well (Saddiq 148). It is clear through the dissenting opinions of these authors, that the war on condom use is not over in West Africa (or sub-Saharan Africa as a whole). It has been shown that education programs without religious affiliation have been successful in educating the public on the dangers of unprotected sex. Though, as one can see through the next section on preventative messages, there are still differing opinions on the methods and messages of HIV/AIDS prevention that negatively affect education and development.

Preventative messages:

Taking a look at HIV/AIDS prevention will give us some more insight into religion’s role in the education and development of societies suffering from the HIV/AIDs epidemic in South Africa and Nigeria. There is a lot of ambivalence in reference to the HIV/AIDS preventative measures taken in South Africa. For example, in Elisabet Eriksson’s study, she focuses on the messages given to young people by Christian church leaders in reference to HIV/AIDS prevention. Three things were evident though this study. There was an issue of breaking the “silence on HIV and AIDS,” there were ambivalent HIV prevention messages given from church leaders to young people and there were gender differences in these HIV prevention messages. In relation to dissenting gender messages; it was noted that 28% of women’s first sexual experiences were ‘unwanted.’ In this case, the church leaders preached that women should not expose themselves too openly and that even though young girls are vulnerable they should be taught to refuse sex. This creates a grave problem in the realm of HIV/AIDS education and prevention as far as women’s health is concerned for, there is a double standard when it comes to women and men being sexually active within the Christian church. Many church leaders preached abstinence but when it came down to it, it was more acceptable for men to be sexually active before marriage than women. This type of preaching promotes the inequality between men and women and since many of the leaders did not condone condom use, there is no outlet for women to feel empowered about their sexuality (Eriksson 105).

Marian Burchardt’s case study in South Africa offers a similar argument in which she explores the gender dichotomy of the AIDS epidemic and expresses that it is really a “gendered disease.” Women are statistically more affected than men because they not only suffer physically but also bear the brunt socially. She explores ways in which religion affects of the lives of women in preventing HIV/AIDS and those that are living with HIV/AIDS. She states that many times these Christian faith-based organizations in South Africa serve to actually promote religious patriarchy instead of female empowerment as we have seen in the previous South African case study.

In Nigeria, we witness similar patterns in preventative messages to those of South Africa. Orubuloye states, “Christianity and Islam tend to be fundamentalist in that they attempt to mould behaviour by spelling out what God wants rather than by justifying those commandments in terms of their philosophic sense or social utility (95).” Thus, teachers of both Islam and Christianity use the epidemic to preach God’s wrath on those who go outside marriage for sexual pleasure. Like we saw in the contraceptive case in Nigeria, Muslim teachers ignore the implications of polygamy. And like in South Africa, Christian preachers use this epidemic to their advantage to encourage monogamy but there are still some very differing messages going out to society. These dissenting messages are a great threat to the illiterate members of the community who tend to turn to religion for answers and not to books or science. This could turn into a grave problem because for the most part, in Nigeria Christian and Muslim leaders do not place enough seriousness on gaining knowledge and access to treatment for people as if converting people is more important. These misunderstandings of the disease could further fuel the epidemic, putting these countries into more precarious positions in the face of economic and social development.

Living with HIV/AIDS:

Throughout this analysis, there is a focus on the patriarchal structures present in the major religions in Africa today as exacerbating the issues with development faced in regards to women’s health in Africa. Concerning this subject, it is also important to touch on the ways in which religion has helped women heal and had guided them through the tough times they have faced in terms of sexual and reproductive health.

As seen in the case study presented by Burchardt, there are many women that have turned to faith-based organizations to seek solidarity in their illness (Burchardt 63). Burchardt outlines some of the drawbacks associated with this but in all, it is important that when living with such a debilitating illness women have a support system and many times these religious groups provide support (64). In Felicitas Becker’s research, we see that not only in South Africa is this reality but in Kenya as well. Women are seeking to understand their illness through religious ideals and practices. Through God and the church, they find the way to move forward on life despite the adversity they may face. This knowledge is significant for, in the face of development, one must find outlooks for education, awareness and helping whilst educating at the same time (Becker 3).

On the other hand, it was found that some women who practiced traditional religions cited this as a factor in not seeking health care (Mills 45). Many of these women that use traditional medicines as a part of their indigenous beliefs are scared and skeptical of the western medicines, especially in the rural areas where education is low and there are a high number of traditional healers. In these cases, elders will talk many women out of using western forms of medicine. This pattern was evident when looking at the receptiveness of ARVs in Kibera, an informal settlement in Nairobi. Many of these women either refused the use of ARVs or stopped using them due to traditional medicinal beliefs (Unge 852).

Due to the fact that religion is significant in Nigerian society, women and men believe immorality may be a cause for HIV/AIDS (Smith Vol. 6). For Igbo Christians in southwestern Nigeria, HIV/AIDS is a social, religious concern and not a medical concern. “AIDS is blamed on the failure to live a good Christian life and protection is promised to those who obey Jesus’ teachings (Smith 429).” Medical education is being ignored in religious education because spreading Christianity seems more important than spreading correct prevention or correct medical treatment because social implications of religion is deeply embedded in Nigerian culture. The Igbo, who are primarily rural farmers, do not have the access to medical information about AIDS so they rely on the people like Christian missionaries or religious leaders with the most knowledge to tell them how to prevent and heal.

Conclusion:

It is evident through these examples that there is an important relationship between women’s health and religion in Africa that cannot be ignored. This relationship is critical to study in the face of this ever-developing and globalizing world. As global citizens we are always looking for solutions and innovations in order to better all of humankind. In order to do this though, we must understand all of the factors at work that are exacerbating or helping these world issues. Each of these case studies provides insight into the specific issues and religious relationships on the topic of women’s health and education in the face of HIV/AIDS in Africa.

In all, only using circumstances in Nigeria and South Africa provides a very limited scope of research for education and development in Africa. The entirety of Africa deserves developmental research not just the areas that are of focus in this study. The methods and discussions in this research can certainly be improved upon or added to in the same way as all research can be enhanced. Hopefully, the selected views in this research gives the reader an idea of what is out there for material on this subject and would also give suggestions for further research to be done.

Works Cited

Aguwa, Jude. “Religion and HIV/AIDS Prevention in Nigeria.” CrossCurrents 60.2 (2010): 208-23. Academic Search Premier. Web. 1 Apr. 2013.

Becker, Felicitas, and P. Wenzel Geissler. “Searching for Pathways in a Landscape of Death: Religion and AIDS in East Africa.” Journal of Religion in Africa 37.1 (2007): 1-15. Academic Search Premier. Web. 11 Mar. 2013.

Burchardt, Marian. “Ironies of Subordination: Ambivalences of Gender in Religious AIDS Interventions in South Africa.” Oxford Development Studies 38.1 (2010): 63-82. Academic Search Premier. Web. 1 Apr. 2013.

Eriksson, Elisabet, Gunilla Lindmark, Pia Axemo, Beverly Haddad, and Beth M. Ahlberg. “Ambivalence, Silence and Gender Differences in Church Leaders’ HIV-prevention Messages to Young People in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.” International Maternal and Child Heath 2.1 (2010): 103-12. Academic Search Premier. Web. 28 Mar. 2013.

Gyimah, Stephen, Jones Adjei, and Baffour Takyi. “Religion, Contraception, and Method Choice of Married Women in Ghana.” Journal of Religion & Health 51.4 (2012): 1359-374. Academic Search Premier. Web. 12 Mar. 2013.

Gyimah, Stephen Obeng, Baffour K. Takyi, and Isaac Addai. “Challenges to the Reproductive-health Needs of African Women: On Religion and Maternal Health Utilization in Ghana.” Social Science & Medicine 62.12 (2006): 2930-944. Academic Search Premier. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Hoel, Nina, Sadiyya Shaikh, and Ashraf Kagee. “Muslim Women’s Reflections on the Acceptability of Vaginal Microbicidal Products to Prevent HIV Infection.” Ethnicity & Health 16.2 (2011): 89-106. Academic Search Premier. Web. 11 Mar. 2013.

Mills, Samuel, and Jane T. Bertrand. “Use of Health Professionals for Obstetric Care in Northern Ghana.” Studies in Family Planning 36.1 (2005): 45-56. Academic Search Premier. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Orubuloye, I.O., John C. Caldwell, Pat Caldwell. “The Roles of Religious Leaders in Changing Sexual Behavior in Southwest Nigeria in an Era of AIDS.” Health Transition Review Vol. 3 (1993): pp. 93-104.

Saddiq, Abdullahi, Rachel Tolhurst, David Lalloo, and Sally Theobald. “Promoting Vulnerability or Resilience to HIV? A Qualitative Study on Polygamy in Maiduguri, Nigeria.” AIDS Care 22.2 (2010): 146-51. Academic Search Premier. Web. 28 Mar. 2013.

Shabi, Iwok Nnah. “Knowledge and Attitude of Women to HIV/AIDS in a Farming Community in Southwestern Nigeria: Challenges for Public Libraries.” Public Library Quarterly Vol. 31 (2012): pp. 246-255.

Smith, Daniel. “Youth, sin and sex in Nigeria: Christianity and HIV/AIDS-related beliefs and behaviour amoung rural-urban migrants.” Culture, Health & Sexuality Vol. 6 (2004): pp. 425-427.

Takyi, Baffour K. “Religion and Women’s Health in Ghana: Insights into HIV/AIDs Preventive and Protective Behavior.” Social Science & Medicine 56.6 (2003): 1221-234. Academic Search Premier. Web. 11 Mar. 2013.

Unge, Christian, Anders Ragnarsson, Anna M. Ekstrom, and Alice Belita. “The Influence of Traditional Medicine and Religion on Discontinuation of ART in an Urban Informal Settlement in Nairobi, Kenya.” Department of Health Sciences 23.7 (2011): 851-58. Academic Search Premier. Web. 1 Apr. 2013.

- This map is intended to show where in Nigeria the rural and urban areas are.

- This map is intended to show where in South Africa the rural and urban areas are.

Mitchell Besser: Mothers helping mothers fight HIV – “Its a medical story, but more than that, it’s a social story.” This TED talk by Mitchel Besser discusses his action to use another source of healthcare: mothers. In a developing country, there is little access to drugs or day-to-day healthcare, so Besser’s mission is to find more attainable healthcare.

World Health Organization – Nigeria – Visit this website for more data and statistics on Nigeria.

World Health Organization – South Africa – Visit this website for more data and statistics on South Africa.

For further reading on education and development in Sub-Sahara:

Hoel, Nina, Sadiyya Shaikh, and Ashraf Kagee. “Muslim Women’s Reflections on the Acceptability of Vaginal Microbicidal Products to Prevent HIV Infection.” Ethnicity & Health 16.2 (2011): 89-106. Academic Search Premier. Web. 11 Mar. 2013.

Mbonu, Ngozi C., Bart Van den Borne, Nanne K De Vries. “Gender-related power differences, beliefs and reactions towards people living with HIV/AIDS: an urban study in Nigeria.” BMC Public Health (2010): pp. 1-10.

Pereira, Charmaine, Jibrin Ibrahim. “On the Bodies of Women: the common ground between Islam and Christianity in Nigeria.” Third World Quarterly Vol. 31 (2010): pp. 921-937.

Usman, Lantana. “Assessing the efficacy of health literacy on rural pastoral women of Northern Nigeria.” The Ahfad Journal Vol. 27 (2010): pp. 59-78.