Walking down a rainy and quiet Archibald street, I approach the steps to the old Ohavi Zedek Synagogue. It felt strange to place my hand on the door knob and open the big white door under the arch of gold Hebrew script. I’ve studied this peculiar red building from the bus stop on the corner almost everyday for what seems like forever and now I was about to go inside. Upon being slightly startled by the massive creek the door made, I gave a half-hearted “hello-O” to which replied, from seemingly everywhere and nowhere at once, Rabbi Jan Salzman, head of the Ruach haMaqom, the first Jewish Renewal congregation in Vermont. Sooner than I could close the door, she comes barreling down a set of stairs on my right hand side in baggy work jeans and a flannel and greets me with a big sigh. “Well” She says, “this is what the Rabbi looks like when she’s off-duty”! I can’t help but smile, this isn’t exactly how I’d anticipated my first meeting with Rabbi Jan, but I was glad and utterly relieved.

She dashed over to a small radio to turn off the music she had playing before I’d come in and we started off on a mini tour of the Synagogue. After you cross through the coat area by the front door, you enter into a grand room, with a balcony and several thin, pointed arch windows on either side, a bimah in the center surrounded by benches and a beautiful ark at the very front. Above the ark, a round window with with stained glass panels making up the Magen David is softly tapped by raindrops. The ceilings are a blue akin to the sky which, Rabbi Jan tells me, is traditional in many Synagogues. Hanging from the ceiling are beautiful antique lamps that came out of an old bank downtown. It has an incredible essence of olden days about it, but it’s age doesn’t show as it’s clear a lot of TLC has gone into caring for this space.

It is more than just looks though, the old Ohavi Zedek Synagogue where Rauch haMaqom congregates has a rich history. Built in 1885 by a group of Lithuanian Jewish Immigrants, who started the Ohavi Zedek congregation, the oldest in Vermont, the synagogue was once the center of the bustling Jewish community in Burlington known as “Little Jerusalem”. The neighborhood spanned through a lot of what is now known as the Old North End, from Archibald and Hyde St. down to Bright St. and so on. These neighborhoods were once full of Jewish groceries, department stores, businesses, hebrew schools and even other Synagogues.

As time went on, the Jewish community of Burlington prospered and spread out around the city and to the suburbs. The big red building is one of the only remaining markers of Little Jerusalem today, and is now home to Ruach haMaqom and one other congregation, Ahavath Gerim, who owns the building.

Rabbi Jan and I sat down in one of the benches in the front and started chatting, after all I did just want to come by and get a sense of the place before I started making recordings and such. And let me tell you, Rabbi Jan really knows her stuff. She begins to tell me about Jewish Renewal and how is very much centered around music and sound, and the incredible amount of musical influence that’s coming out of Jerusalem these days. Though, she mentions, many if not most of the people that come to Ruach Maqom services are just discovering their faith for the first time, or are part of another faith or neither, so the make up of the congregation is wholly interfaith. We nerd out for a bit about language and sound and acoustics and I help her rearrange some of the benches for that evening’s service. As I leave I’m filled with this rush of excitement to delve into this project with someone who is remarkably enthusiastic about space and sound, particularly the sounds of THIS space.

Later that day, at 6 p.m., I return to the Synagogue for Shabbat. I walk in and now the room is all lit up and there are a few people scattered about the benches, most sitting towards the back. I take a seat towards the back hoping to be a fly on the wall even though Rabbi Jan joyously urges everyone to move up towards the front. I set my recorder down next to me, hidden adn hit the little record button as soon as the service starts. Recording is technically not allowed on the Sabbath but Rabbi Jan said that it would be alright as long as I was discrete which was my course of action any way. I open up my Seder that I picked up at the door and flip through it, noticing that it’s almost entirely in Hebrew, with some songs translated in English. Some more people are filtering in as the service is beginning and lighting small candles before they take a seat. Looking around at the different faces, it’s not what I’d initially imagined. There were some older, more traditional looking people, some college kids, a few very young kids and everything in between. The service started off with an upbeat song that Rabbi Jan strummed on her little acoustic guitar, and at first everyone seemed shy to sing along. I was relieved to see that I wasn’t the only beginner in the crowd.

As the song progressed I noticed small thumping noises, growing louder and louder and looked around at people tapping and stomping their feet with the song. Many of them had their eyes closed swaying slightly with the sound of the guitar, a glowing look of serenity on their faces. Rabbi Jan sang and danced around at the front on a colorful rug that I’d helped her roll out earlier, and her warmth rang out through the whole room. We talk about sonic experiences and what being a part of a particular soundscape is like, but you can really only say so much about a feeling. The way that the sounds of the people and the benches creecking and the kids in the back whispering and the guitar humming, come up and and over and through you makes you hyper aware of your own self being a part of this grander composition. Rabbi Jan incorporates a variety of instruments into the services including a guitar, bongos and an Indian Shruti box. She was telling me that “since it was built before microphones, the acoustics of this place are really, really special” and I agree, this was certainly not a place built for silence.

After the service was over, my mind was racing with all of these thoughts on the environment that Ruach haMaqom creates and how the sound shapes the space and the space shapes the sound as well. When I went to talk to Rabbi Jan a couple weeks later, she had so much insight on the purpose of sound in Jewish Renewal and, specifically how it functions within a congregation that is made up largely of people who haven’t had much connection to their spirituality in the past. According to her, sound is the utmost essential component of Jewish Renewal, as a means for people to connect spiritually through the pure sound of the language and music rather than the content of the liturgy. She also explains the significance of “Call and Response” with in the services saying, “The leader sings out A and you, the congregation, respond B and that, in itself, creates this sonic exchange between one group of people in the room and another group of people in the room. And that gets further amplified by the adoption of Kirtan chant and other forms of chant that has been integrated in Jewish Renewal liturgical experience”. She goes on to explain how she spends a lot of time thinking about the arrangement of the benches and how to best create this sense of oneness, amongst the people in the space during the service. “In a room like this, you physically feel the music. And theres definitely vibration because the sound is trapped in really excellent acoustics and also we’re singing in close proximity to each other and I think that there is a level of experience that absolutely occurs on the physical level that in a way is healing”.

Throughout this conversation, I’m drawing connections to the discussions we had in class on sound and the body and deep listening that the Kapchan articles presented. It was exciting to see these ideas take hold in an entirely different environment from which they were conceived. Sound is central in creating a single body within the Shabbat service and is achieved through a variety of modalities. One of the things Rabbi Jan was explaining to me is that the words and the songs we sing at each service are essentially the same, but the tones and rhythm of the words change according to the season, holiday, what time of day it is and what part of the service you’re in. Another, and potentially most important in the sound-body component, is that almost every song is sung in Hebrew, so no one has any idea what they’re saying unless they’re highly proficient which most people are not. The idea behind this is not to be decoding meaning while you’re singing the words but to obtain a spiritual feeling from the actual phonemes and sounds of the words. The experience is sonic to it’s core, and the goal is not in anyway to be correct and pronounce words perfectly but to create a unique collection of everyone’s imperfections all at a single moment in time because that is what leads to a unified translation of the physical body into a metaphysical body. This feeling is tangible, everyone comes in by themselves and starts off very timid, because no one wants to be the loudest voice in the room, but then as it progresses the sound and vibrations start to flow more freely and move through the space in a strong rush, bouncing off the back wall, almost like waves crashing.

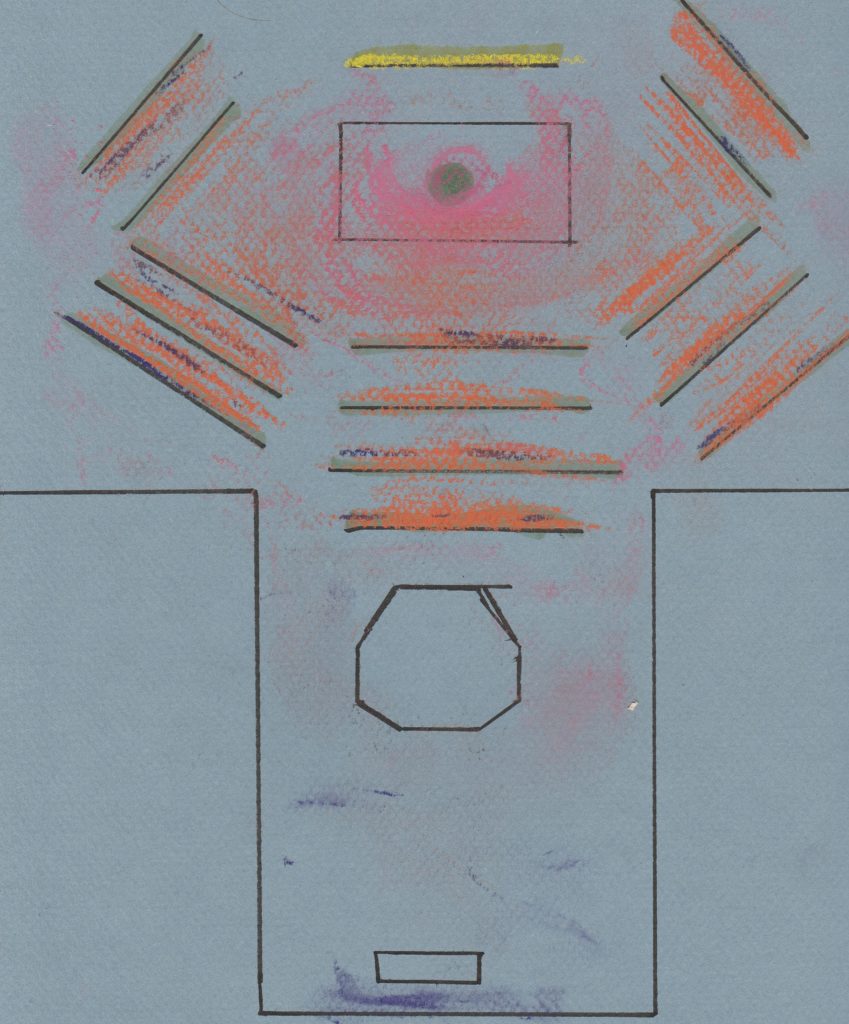

My sound composition is meant to convey most accurately just the amount and variety of the music that is incorporated into the Shabbat services at Ruach haMaqom. There is a little bit of English but I think the composition is highly reflective of the way that the singing of Hebrew can be a means for reaching that feeling of spirituality. I added in what Rabbi Jan’s thoughts were on the sound in the space because it is such an important component of what Jewish Renewal does and is. My sound map of the Synagogue that I’ve created is representative of the movement of sound in the space using color. It looks messy but I purposefully wanted to represent the free-flowing, central movement of the sound in the space.

The space itself, too, is wholly imperfect which is what gives it such a spirit of being lived in, being a home and a place where many others have gathered before and will gather again. Rabbi Jan uses the Yiddish word “yichus” to describe it, which is meaning have a sense of lineage, and of tradition, but not in the sense that it is dated or obsolete. I didn’t not want my representation of it to be rigid and dull because that would be a disservice to the Synagogue’s true eminence. The yellow lien represents the ark at the front, the green dot and red coloration represents the sound of the Rabbi and the green lines are the benches which the congregation sits and the orange is where their sound moves. The purple is representative of all the little odd sounds made by benches and floor boards and doors opening and shutting. Where they all mix, is where the body is created.

My last question to Rabbi Jan was what she was most excited about for the congregation. She explained that one of her main goals was to make it into a resource that can be opened up to the community, expanding to events like concerts, theatre and poetry readings and making it a space where people of any faith can connect with one another and find a means of spirituality. Another was to preserve the life of the building itself, and fix it up so that it can live on and continue to be a not only a space for Judaism but an interfaith gathering space for people to enjoy in the years to come.

Sources:

Rabbi Jan Salzman, Ruach haMaqom, http://www.ruachhamaqom.org/

Kapchan, Deborah “Learning to Listen: The Sound of Sufism in France”

Kapchan, Deborah. “Body.” In Keywords in Sound, edited by David Novak and Matt Sakakeeny

Vermont PBS Documentaries, Little Jerusalem