I was fortunate to kick off the UVM History Department’s Faculty Research Seminar series yesterday, sharing a presentation on “Bureaucracy and Humanity: Exploring the Records of the US Consular Service” with terrific colleagues and graduate students. I resisted providing an actual title until the last possible moment — the start of the presentation — but my advertising blurb promised “tales of fraud and death, bureaucratic grandeur, and State Department attempts at art, plus a new gadget.” I won’t put the whole thing up here, but here are some highlights, minus most of the analytical bits:

THE NEW GADGET: The ScanSnap SV600 Contactless Scanner, which was what caught my eye in terms of new technology when I was at Archives II in College Park this summer. I’m looking forward to really using it when I return this fall, but so far, so awesome.

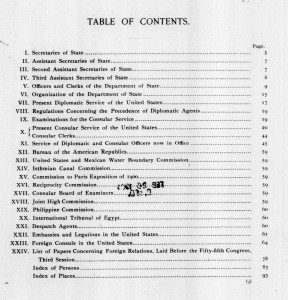

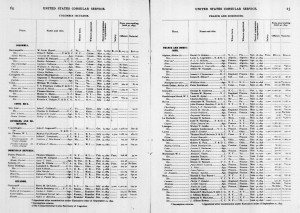

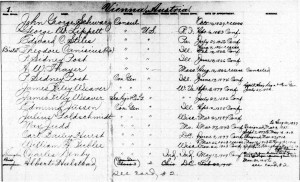

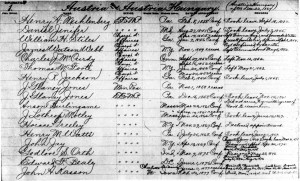

BUREAUCRATIC GRANDEUR: Members of Congress, the public, and some central office personnel at the Department of State certainly had lots of suggestions about how to improve the US Consular Service, but a lot of ideas came from consuls themselves. After the creation of inspectors — holding the title Consuls General At Large — in 1906, there were more and grander suggestions, most aimed at improving efficiency and uniformity of practice. Many of the ideas were very much in line with contemporary efforts for Taylorist or similar reforms of business processes. Most were deemed impracticable — or even “revolutionary” — by the central office, but they did push through a reform that required US consulates throughout the world to be open to the public from 9 am to 4:30 pm Monday through Friday and from 9 am to 1 pm on Saturdays. The discussion began in 1913 after one of the At Larges expressed his dismay that the consulate at Riga was only open from 10 to 3. The central office solicited opinions from the rest of the At Larges, who split on the issue: some thought local customs and the discretion of individual consuls should prevail, while others emphasized the need to match the norm in the United States and thus accommodate the expectations of members of the American public traveling abroad. The central office went for the latter position and sent rather harshly worded instructions to specific consuls to conform with the new rules. I’m not sure (yet?) how effective the reform was, especially because it was done in 1916 in the midst of World War I — the very definition of “extenuating circumstances” — but the documents clearly evidence the frustrations of all parties.

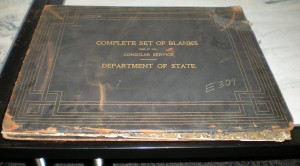

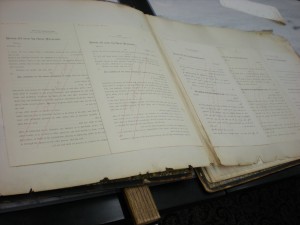

STATE DEPARTMENT ATTEMPTS AT ART: There was a visualization — poorly photographed on my part — of one of the reform plans, plus an At Large’s drawing of what a proper US Consular Agency office should look like. But my personal favorite still remains the oversize scrapbooks of consular forms assembled for as yet unknown reasons in approximately 1890:

Sadly, even though they promise a “Complete Set of Blanks” — and, thus, potentially, an expression of all of the service’s bureaucratic functions — it isn’t actually complete. There is quite a bit in there, however, though they definitely don’t deserve points for effective or aesthetically pleasing use of space.

DEATH: When an American died abroad, consuls were responsible for reporting the death to the State Department and ensuring the proper handling of the body and the deceased estate/personal property. I showed some examples of the reports generated by consuls stationed in England in 1913; they’re especially easy to find for the Decimal File years (1910-29; see this post for more information). They could be useful sources for scholars interested in a variety of historical subfields, as they provide information about citizenship, the circumstances of death, familial relations, travel patterns, and mortuary practices, among other things. I was struck by the number of women evident in the records. There’s a lot of very raw emotion in there, too.

FRAUD: Consuls also worked to protect US citizens from various kinds of fraud. In Anglo-American relations, a great deal of time was spent attempting by various means to communicate to Americans that “THERE ARE NO GREAT UNCLAIMED ESTATES IN ENGLAND.” It was popular scam for people who claimed to be British attorneys to put advertisements in newspapers announcing that they were looking for the heirs to “the [insert common surname here] estate,” valued at however many millions of pounds. The victims of the fraud paid for copies of wills, attorneys fees, genealogical reports, and other things in pursuit of claims. Requests for assistance in furthering the claims or establishing the legitimacy of the advertisements came to the legation and consular staff so often that, in 1884, they had a form cover letter and a circular printed to send in response. (And still in use in 1914.) While many circulars I have seen are quite tactful, this one isn’t; if nothing else, the ones I’ve read before have been addressed to specific members of Congress, while this began as internal State Department communications. You can view the original on pages 224-29 in the 1884 volume of Foreign Relations of the United States here.